Variation of Wills

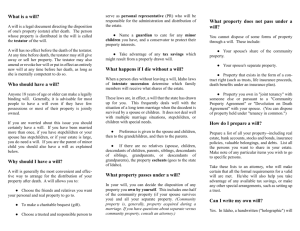

advertisement