INTRODUCTION TO CONTRASTIVE LINGUISTICS

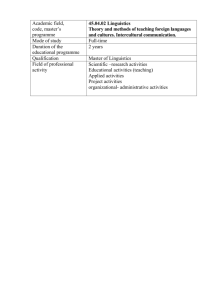

advertisement

Introduction to Contrastive Linguistics Doctorand Adel Antoinette SZABÓ Universitatea « Babeş-Bolyai » Cluj-Napoca The theory of translation can be included, first of all, into the contrastive analysis, as a branch of language comparison. Therefore, a theoretical approach to the general principles that govern the disciplines that deal with the parallelism between languages is absolutely necessary. 1.1. Disciplines inside contrastive linguistics Linguistics can be subdivided into several branches according to the perspective of the study or to the focus on a certain category of phenomena or hypotheses. John Lyons1 identifies four such distinctions: A. general – descriptive; B. diachronic – synchronic; C. theoretical – applicative; D. macrolinguistic – microlinguistic. Following some of R.R.K. Hartmann’s2 suggestions and Jeffrey Ellis’s3 classification of the branches of comparative linguistics we could draw an explanatory chart of the disciplines that deal with the parallelism between languages. Comparative Linguistics is divided into two large branches, namely, General Comparative Linguistics and Specialized Comparative Linguistics. The former is divided into Descriptive (Synchronic) Linguistics, with its two subdivisions, Comparative Descriptive Linguistics and Typological Linguistics, and, the second, Historical Linguistics. Specialized Comparative Linguistics has three subdivisions, namely, Genetic Comparative Linguistics, the Theory of Linguistic Contact, and Areal Linguistics. The Theory of Linguistic Contact can be divided into the Theory of Bilingualism, the Theory of Borrowing, and the Theory of Areal Convergency. The Theory of Bilingualism includes Predictive Contrastive Analysis, Deep Structure Contrastive Analysis, Error Analysis, the Theory of Creolization and the Theory of Translation. 1.2. A dictionary of contrastive terminology General Comparative Linguistics. John Waterman4 and Victoria Fromkin, Robert Rodman5 offer a survey of the most important forerunners of modern comparative linguistics. In the 19th century 1 John Lyons, Language and Linguistics, Cambridge University Press, 1981, p. 34. R.R.K. Hartmann, Contrastive Textology. Comparative Discourse Analysis in Applied Lingusistics, Julius Groos Verlag Heidelberg, [1980], p. 20. 3 Jeffrey Ellis, Towards a General Comparative Linguistics, London, The Hague, Paris, Mouton & Co, 1966, p.3. 4 John Waterman, Perspectives in Linguistics. An account of the background of modern linguistics, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1963. 5 Victoria Fromkin, Robert Rodman, An Introduction to Language, NewYork,Chicago,[etc]., Holt, Rinehart & Winston Inc., 1984. 2 Rasmus Kristian Rask formulates a series of principles and methods that set the foundation for modern comparative linguistics. Jakob Grimm publishes a comparative grammar of all Germanic languages. Franz Bopp includes the Indo-European languages in his comparative studies, extends his research to morphology, and demonstrates the importance of Sanscrite for the comparative studies. August Schleicher is well-known for his theory of related languages, for his method of reconstruction of a mother-tongue, and also for his classification of languages into types. August Fick established a model of the Indo-European vocabulary, by applying the theory of language genealogy. A number of other researchers contributed to the theory and methods of historical comparative linguistics : Hermann Paul (Principles of Linguistic History), Karl Brugman and Bertold Delbruck, Hermann Hirt (Indo-German Grammar), Antoine Meillet (Introduction to the Comparative Study of Indo-European Languages). The Indo-European comparative studies witnessed a spectacular rebirth in the 20th century, in the United States, by applying the methods of comparison and reconstruction of languages, to the languages of primitive communities. Edward Sapir proved that several tribes from the North and from the South of the United States were genetically related. Leonard Bloomfield studied the ancient Algonkin language, Isidore Dyen studied the Malayo-Polinesian languages. Joseph Greenberg classified the indigenous languages from Africa. Morris Swadesh is considered to be the father of glotochronology, also known as the lexical-statistical dating of linguistc relations. Typological Linguistics. Ariton Vraciu6 proposes a classification of languages, using the concepts of meaning and form of the language as criteria: a) isolating languages; b) aglutinant languages; c) flexionary languages ( synthetical languages and analytical languages). Edward Sapir7 completes the traditional classification, on the basis of three criteria formulated by himself: a) the degree of synthesis; b) the mechanics of synthesis; c) the nature of concepts. Sapir identifies, thus, four fundamental types of languages: A. Simple, relationally pure languages, with no modification of the radical (affixes or internal change). B. Complex, relationally pure languages: pure syntactic relations, with the modification of the radical. C. Simple, relationally combined languages: syntactic relations that manifest through associations with significant concepts, without the modification of the meaning of the radical. D. Complex, relationally combined languages: syntactic relations expressed in a combined form with the modification of the radical through affixes or internal change. Using the degree of synthesis as a criterium, Sapir divides languages into the following types: a) analytic languages; b) synthetic languages; c) polisynthetic languages. The mechanics of synthesis divides languages into: a) isolating languages; b) aglutinant languages; c) merging languages; d) symbolyzing languages. 6 7 Ariton Vraciu, Lingvistica generală şi comparată, Bucureşti, Editura didactică şi pedagogică, 1980. Edward Sapir, Language. An introduction to the study of speech , New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1949. General linguistics admits, as a principle, the four types of languages, also identified by Ariton Vraciu: a) the isolating/amorphous/radical type (e.g. Chinese, Vietnamese); b) the aglutinant type (e.g. Turkish and Mongolian languages, Japanese, Armenean); c) the flexionary type - synthetic languages (e.g. Sanscrite, Ancient Armenean, Ancient Slavic, German, Russian); - analytic languages ( e.g. Romance languages, English, Greek) d) the polisynthetic type (e.g. Native American languages). Dumitru Chiţoran8 notices the growing interest of modern linguistics for two apparently opposite perspectives, subordinated to typological linguistics: linguistic relativism and linguistic universals. Both theses are based on the relation between the structure of the language and the structure of the universe. The linguistic relativism stipulates that the structure of the language directly reflects the structure of the universe and of the human mind, being considered the very moulder of the latter. This theory was formulated by Wilhelm von Humboldt, whose work represents the dawn of several extremely important currents in modern linguistics, the starting point for the main directions in the philosophy and theory of language. Humboldt, in his works, takes into discussion several issues connected with the theory of the language: the nature and the functions of the language; the relation between language and thought, language and speech, speech and comprehension, language and nation; the evolution and typology of languages; the linguistic sign, language regarded as a system9. The hypotheses of the linguistic relativism have become well-known through Edward Sapir’s and Benjamin Lee Whorf’s works, and it circulated under the name of Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. In the introduction to Whorf’s book Language, Thought and Reality10 Stuart Chase identifies two cardinal hypotheses: 1. all superior levels of language depend on language; 2. the structure of the language influences the individual way of perception of the environment. The very image of the universe changes from one language to another. The interest that linguists took in the differences between languages shifted to the common elements of all languages. This lead to the attempt of establishing a set of laws that govern all languages, a set of universal features of language, generating the hypothesis of linguistic universals. The list of linguistic universals varies from one researcher to another, from one point of view to another. Eugenio Coseriu11 identifies two types of linguistic universals: a) essential universals: - necessary universals: they are conceptual, therefore they cannot constitute a basis for description; - possible universals: a particular phonological or grammatical system. b) universality as a historical generality. Another distinction noticed by Coseriu lies between the functional/ semantic universals and the designation universals. The delimitation of the possibilities of designation is called by Coseriu significance. Significance and designation, together, represent a new sign, with a superior content, called by Coseriu meaning12. The meaning can be found only in texts, inside the discourse. Dumitru Chiţoran, Elements of Structural Semantics, Bucureşti, Editura didactică şi pedagogică, 1973. Teorie şi metodă în lingvistica din secolul al XIX - lea şi începutul secolului al XX - lea. Texte comentate. Bucureşti, Facultatea de limbi străine, 1984. 10 Benjamin Lee Whorf, Language, Thought and Reality, The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Massachussetts, 1956. 11 Eugenio Coseriu, Lingvistica integrală; interviu cu Eugeniu Coseriu realizat de Nicolae Saramandu, Bucureşti, Editura Fundatiei Culturale Române, 1996. 12 Semnificaţie, designaţie, sens, in Coseriu’s own terminology; Eugenio Coseriu, Prelegeri şi conferinţe, (1992 -1993), Iaşi, Institutul de Filologie Română “A. Phillippide”, 1994, p. 40. 8 9 In linguistics, and also in grammar, Eugenio Coseriu ascertains two dimensions unified through two language universals: homogeneity/unity (syntopic, synstratic, synphrastic), and variety (diatopic, diastratic, diaphasic). Another universal dimension would be alterity, meaning that language belongs also to the others, to a community, not only to the speaker. Ronald W. Langacker13 finds two distinctive categories inside the linguistic universals: absolute universals (features that are common to all languages) and universal tendencies (not altogether universal, but features that cannot be explained by chance, borrowing or relation). Dumitru Chiţoran14 discovers several universal elements, present in all languages: the pattern of languages, syntactic and semantic elements/rules, some aspects of the phonological system of languages, age, sex, dimensions, movement; semantic relations (synonimy, antonymy, conversion, hyponymy). According to Joseph B. Casagrande15, language has a generic function, with reference to the means of orientation of the individual in the cultural universe he comes in contact with: the three personal pronouns (I, you, he), family relationships, names, the terms of possession, the general terms for the human body parts, and for the conscious psycho-physiological processes, a general frame for space and time. Victoria Fromkin and Robert Rodman16 offer a list that includes several general features of language, and also several others, specific to particular languages: the existence of people requires the existence of language, the ability of languages to express ideas, linguistic change, the arbitrary connection between sounds and the significance of words, the existence of a finite number of sounds used to build an infinite number of sentences, the existence of grammatical categories, the existence of vowels and consonants. *** Genetic Comparative Linguistics. Another classification of languages can be made according to their relation. The terminology used by linguists was borrowed from family relationships: a „proto-language” can be the „mother-tongue”, and its descendants, can be „daughter-tongues”. In time the „daughter-tongue” may become a „mother-tongue”, and it would divide in several dialects, that would hold remarkable distinctions between them. These dialects would evolve on their own, and would be considered as separate but related languages. Thus, the genealogy tree that represents the relations between languages may become very complex. *** Linguistic change, subordinated to the theory of linguistic contact, was also studied by comparative linguistics. In the article Linguistic Change Does Not Exist 17, and also in his book Synchrony, Diachrony and History; The Problem of Linguistic Change18, Eugenio Coseriu views linguistic change from the standpoint of a „dynamic conception of language as creativity”. In his 13 Ronald W. Langacker, Language and its structures : some fundamental linguistic concepts, New York, [etc.], Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. 1968, p. 247. 14 Dumitru Chiţoran, Op. cit. 15 Joseph B. Casagrande, Language Universals in Anthropological Perspective, in Universals of Language, Joseph H., Greenberg (ed. ), Report of a Conference held at Dobbs Ferry, April 13 – 15 1961, The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1963. 16 Victoria Fromkin, Robert Rodman, Op. cit. Eugenio Coseriu, Linguistic change does not exist, în “Linguistica Nuova ed Antica”, Rivista Classica Medioevala e Moderna, Anno – I, 1983. 18 Eugenio Coseriu, Sincronie, diacronie şi istorie; problema schimbării lingvistice, Bucureşti, Editura Enciclopedică, 1997. 17 oppinion, the concept of linguistic change can be best understood if we start from the assumption that it „does not exist”. By non-existence Coseriu means: a) the non-existence of change in the form largely accepted in linguistics; b) the imperceptibility of its existence in the sense in which it really takes place; c) the fact that a newly-created linguistic phenomenon may often be interpreted at one and the same time as change and non-change: as renewal and application.19 Therefore, Coseriu distinguishes three different problems which belong to three different levels: a) the universal problem of linguistic change (why do languages change at all?) b) the general problem of linguistic change (how and under what intra- and extralinguistic conditions do languages normally change?) c) the historical problem of every individual change, that is, the problem of justifying the creation of a particular tradition and possibly the replacement of an earlier tradition. The motivation of the linguistic change is also found by Coseriu, namely: the linguistic creation, regarded both as invention, and as an innovation in language. One of the sources of the linguistic change is borrowing from another language, a phenomenon studied by the theory of borrowing, directly derived from the theory of linguistic contact. Victoria Fromkin and Robert Rodman20 define and classify borrowing into: a) lexical/intimate borrowing : - direct borrowing: e.g. feast (Engl.) was directly borrowed from French, fête, borrowed from the Latin festa. - indirect borrowing: e.g. algebra, alcohol, bismuth are Arab words, borrowed by the English language through Spanish.. b) cultural borrowing: Up until the Norman Conquest, when an Englishman sacrificed an ox for food, he ate o;, when he sacrified a sheep he ate sheep, the same with pig. But the ox served for the Normans became beef (boeuf), the sheep became mutton (mouton), and the pig became pork (porc) The same authors identify the causes of borrowing, that is, the need to name new things, new concepts, new places. *** The theory of bilingualism studies a series of phenomena, such as: linguistic contact, interference, and transfer. Victoria Fromkin and Robert Rodman21 point out that the situations when a linguistic community is in contact with another are called linguistic contact situations, and they generated the theory of bilingualism. The linguistic contact appears when a speaker has to use a second language apart from his mother tongue, even if he uses it only partially or with imperfections. Those cases of deviation from the norms of one or another of the two languages used by the bilingual, therefore as a result of language contact, are called interference 22. The greater the difference between the two systems, the larger the area of interference. Interference is due to another phenomenon that appears in the case of languages in contact, namely, the transfer. Transfer , largely studied by Uriel Weinreich23 could be defined as the process of interpretation of the grammar of one language in terms of another. The predictive contrastive analysis lies in close connection with the theory of bilingualism and with the phenomenon of interference, and its purpose is second language teaching. Robert J. 19 Eugenio Coseriu, Op. cit., p. 55. 20 Victoria Fromkin, Robert Rodman, Op. cit. Victoria Fromkin, Robert Rodman, Op. cit. 21 22 M.A.K. Halliday, Angus McIntosh, Peter Strems, The Linguistic Sciences and Language Teaching, London, Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd., 1968. 23 Uriel Weinreich, Languages in Contact. Findings and problems, seventh printing, The Hague - Paris, 1970 . DiPietro24 considers that, in applying the results of contrastive analysis to the predictive analysis of mistakes, one should take into consideration both the performance factors, and the development of the competence inside the areas of contrast. Predictive analysis represents the preventative step in erradicating mistakes. The situation when two communities come into contact gives birth to creole or pidgin languages. Creole languages are studied by the theory of creolization25. Creole languages are the result of the contact of the language of the colonists (French, English, Portuguese, Spanish) and the language of the slaves brought to the colonies, such as Creole French in Haiti, Jamaican English, Gullah from Georgia and South Carolina, Cajun in Louisiana, Krio in Sierra Leone. The deep structure contrastive analysis is based on a universal model of language26. Some linguists such as Noam Chomsky27 and Charles Fillmore28 initiated the hypothesis that all sentences have a surface structure and a deep structure. By applying the notions of deep structure and surface structure, the fact that the crucial contrast area is the one that lies between the deepest structure and the most surface one, becomes evident. The differences between languages can be observed at any level that lies between the deep structure and the surface structure. In this way, we can even quantify similitudes between languages. The theory of translation is is a branch of the comparative-descriptive linguistics, and it deals with a certain type of relations between languages. It also has a biunivocal relation with the theory of bilingualism. The theory of translation finds its resources in a general linguistic theory that can offer answers to issues such as: the theoretical validity of the equivalence in translation, the limits of translatability, and also the solution to the practical problem of finding equivalences in translation29. The geographical closeness of several linguistic communities leads to the appearance, inside these communities, of certain common features - affinities – that allow their grouping into linguistic associations 30. They are noticeable even when the languages are only distantly related. This phenomenon was called by Ducrot and Schaeffer31 areal convergency, and areal linguistic community by Uriel Weinreich32. *** Applying the theory of the evolution of the human species to the study of languages, researchers found out that the evolution of the lexical forms, once that they detached from the proto-language, depends on their geographical localization. The regional differences of vulgar Latin, that have become later Romanian, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, were studied according to the geographical distance between the place where they were found, and their place of 24 Robert J. DiPietro, Language Structures in Contact, Rowley, Massachussets, Newbury House Publishers, 1971. Oswald Ducrot, Schaeffer, Jean – Marie, Noul dicţionar enciclopedic al ştiinţelor limbajului, Bucureşti, Babel, 1996. 26 Mircea Gheorghiu, Probleme de tipologie contrastivă a limbilor. Determinanţi congruenţi de relaţie, [s.l.], Editura Ştiinţifică şi Enciclopedică, 1981. 27 Noam Chomsky, Syntactic Structures, The Hague, Mouton, 1957. 28 C. Fillmore, ‘The Case for Case’, în Bach E. and R. Harms, (eds.),Universals in Linguistic Theory, Holt, New York, 1968. 25 James C. Catford, Traducerea: definiţie şi tipuri generale, în Ferdinand de Saussure. Şcoala geneveza. Şcoala sociologica. Direcţia funcţionala. Şcoala britanică. (Texte adnotate), Bucureşti, 1985. 30 Robert J. DiPietro, Op. cit., p. 27. 31 Oswald Ducrot, Jean – Marie Schaeffer, Op. cit., p.96. 32 Uriel Weinreich, Weinreich, Uriel, Languages in Contact. Findings and problems, seventh printing, The Hague Paris, 1970, p. 89-97. 29 origin. These studies were called areal linguistics33 or linguistic geography34. Linguistic geography developed at the end of the 19th century by the elaboration of national linguistic atlases. These appeared from the need to describe and study the system of a language also from the point of view of the contemporary state of the language, not only from the perspective of the differences between the literary language or from a historical perspective. REFERENCES Casagrande, Joseph B., Language Universals in Anthropological Perspective, in Universals of Language, Joseph H., Greenberg (ed. ), Report of a Conference held at Dobbs Ferry, April 13 – 15 1961, The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1963. Catford, James C., Traducerea: definiţie şi tipuri generale, în Ferdinand de Saussure. Şcoala geneveza. Şcoala sociologica. Direcţia funcţionala. Şcoala britanică, Bucureşti, 1985. Chiţoran, Dumitru, Elements of Structural Semantics, Bucureşti, Editura didactică şi pedagogică, 1973. Chiţoran, Dumitru, Alexandra Petrovanu, Some aspects of Translation in the Light of Generative Grammar, în “Revue roumaine de linguistique”, tome XVI, nr. 5, 1971. Chomsky, Noam, Syntactic Structures, The Hague, Mouton, 1957. Coseriu, Eugenio, Lingvistica integrală; interviu cu Eugeniu Coseriu realizat de Nicolae Saramandu, Bucureşti, Editura Fundaţiei Culturale Române, 1996. Coseriu, Eugenio, Sincronie, diacronie şi istorie; problema schimbării lingvistice, Bucureşti, Editura Enciclopedică, 1997. Coseriu, Eugenio, Linguistic change does not exist, în “Linguistica Nuova ed Antica”, Rivista Classica Medioevala e Moderna, Anno – I, 1983. DiPietro, Robert J., Language Structures in Contact, Rowley, Massachussets, Newbury House Publishers, 1971. Ducrot, Oswald, Jean – Marie Schaeffer, Noul dicţionar enciclopedic al ştiinţelor limbajului, Bucureşti, Babel, 1996. Ellis, Jeffrey, Towards a General Comparative Linguistics, London, The Hague, Paris, Mouton & Co, 1966. Fillmore, C., ‘The Case for Case’, în Bach E. and R. Harms, (eds.), Universals in Linguistic Theory, Holt, New York, 1968. Fromkin, Victoria, Robert Rodman, An Introduction to Language, NewYork, Chicago,[etc]., Holt, Rinehart & Winston Inc., 1984. Gheorghiu, Mircea, Probleme de tipologie contrastivă a limbilor. Determinanţi congruenţi de relaţie, [s.l.], Editura Ştiinţifică şi Enciclopedică, 1981. Halliday, M.A.K., Angus McIntosh, Peter Strems, The Linguistic Sciences and Language Teaching, London, Longmans, Green and Co. Ltd., 1968. Langacker, Ronald W., Language and its structures : some fundamental linguistic concepts, New York, [etc.], Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. 1968. Lyons, John, Language and Linguistics, Cambridge University Press, 1981. Hartmann, R.R.K., Contrastive Textology. Comparative Discourse Analysis in Applied Lingusistics, Julius Groos Verlag Heidelberg, [1980]. Sapir, Edward, Language. An introduction to the study of speech , New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1949. Dumitru Chiţoran, Alexandra Petrovanu, Some aspects of Translation in the Light of Generative Grammar, în “Revue roumaine de linguistique”, tome XVI, nr. 5, 1971. 34 Colin H. Williams (ed.). (1988). Language in Geographic Context, Clevedon, Philadelphia, Multilingual Matters Ltd. 33 Teorie şi metodă în lingvistica din secolul al XIX - lea şi începutul secolului al XX - lea. Texte comentate. Bucureşti, Facultatea de limbi străine, 1984. Vraciu, Ariton, Lingvistica generală şi comparată, Bucureşti, Editura didactică şi pedagogică, 1980. Waterman, John, Perspectives in Linguistics. An account of the background of modern linguistics, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1963. Weinreich, Uriel, Languages in Contact. Findings and problems, seventh printing, The Hague Paris, 1970. Whorf, Benjamin Lee, Language, Thought and Reality, The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Massachussetts, 1956 Williams Colin H., (ed.). (1988). Language in Geographic Context, Clevedon, Philadelphia, Multilingual Matters Ltd.