Violent Seismic Activity Tearing Africa in Two by Axel Bojanowski

advertisement

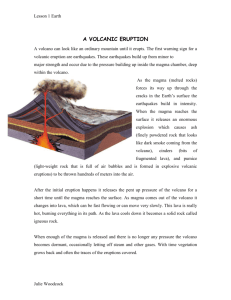

Violent Seismic Activity Tearing Africa in Two by Axel Bojanowski The fissures began appearing years ago. But in recent months, seismic activity has accelerated in northeastern Africa as the continent breaks apart in slow motion. Researchers say that lava in the region is consistent with magma normally seen on the sea floor -- and that water will ultimately cover the desert. Cynthia Ebinger, a geologist from the University of Rochester in New York, could hardly believe what the caller from the deserts of Ethiopia was saying. It was an employee at a mineralogy company -- and he reported that the famous Erta Ale volcano in northeastern Ethiopia was erupting. Ebinger, who has studied the volcano for years, was taken aback. The volcano's crater had always been filled with a bubbling soup of silver-black lava, but it had been decades since its last eruption. The call came last November. And Ebinger immediately flew to Ethiopia with some fellow researchers. "The volcano was bubbling over; flaming-red lava was shooting up into the sky," Ebinger told SPIEGEL ONLINE. The earth is in upheaval in northeastern Africa, and the region is changing quickly. The desert floor is quaking and splitting open, volcanoes are boiling over, and seawaters are encroaching upon the land. Africa, researchers are certain, is splitting apart at a rate rarely seen in geology. The first fracture appeared millions of years ago, resulting in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. The second fracture, stretching south from Ethiopia to Mozambique, is known as the Great Rift Valley, and it is lined with several volcanoes. Millions of years from now, it too will be filled with seawater. Could Go Quickly But in the Danakil Depression, in the northern part of the valley, the ocean could arrive much sooner. There, low, 25 meter (82 foot) hills are the only thing holding back the waters of the Red Sea. The land behind them has already dropped dozens of meters from previous levels and white salt deposits on the desert floor testify to past encroachments of the sea. But lava soon choked off its access. For now, no one can really say when the sea will finally flood the desert. But when it does, it could go quickly. "The hills could sink in a matter of days," Tim Wright, a fellow at the University of Leeds' School of Earth and Environment, said at a recent conference hosted by the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco. In the last five years, the geologic transformation of northeastern Africa has "accelerated dramatically," says Wright. Indeed, the process is going much faster than many had anticipated. In recent years, geologists had measured just a few millimeters of movement each year. "But now the earth is opening up by the meter," says Loraine Field, a scholar at the University of Bristol who also attended the conference. Earth tremors cause deep fissures to form in the desert floor and the ground in East Africa is shattering like broken glass. Researchers in the Gulf of Tadjoura, which juts into Djibouti from the Gulf of Aden, have recently registered a barrage of seismic shocks. "The quakes are happening on the mid-ocean ridge," Ebinger reports. Shifting Tectonic Plates Lava gushes out of fissures in these underwater mountain ranges to constantly create new earth crust -- when it hardens, it becomes part of the sea floor. As the magma surges upward, it spreads the ocean floor on both sides, shifting tectonic plates and causing tremors. In recent months, the quaking in the Gulf of Tadjoura has been getting closer and closer to the coastline. As Ebinger explains, the splitting of the ocean floor will gradually extend to dry land. This is already the case along some fault lines in the Ethiopian desert, creating a geological spectacle that can otherwise only be witnessed deep below the surface of the ocean. Even the pattern of earthquakes supports the conclusion that the desert landscape is transforming into a deep seafloor, according to a recent article in the Journal of Geophysical Research published by Zhaohui Yang and Wang-Ping Chen, two geologists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The researchers have recorded several strong earthquakes at a shallow depth in northeastern Africa similar to ones that are otherwise only seen on mid-ocean ridges far out at sea. In recent months, researchers have also recorded an up-tick in volcanic activity. Indeed, geologists have discovered volcanic eruptions near the earth's surface at 22 places in the Afar Triangle in northeastern Africa. Magma has caused fissures up to eight meters (26 feet) wide to open up in the ground, reports Derek Keir from the University of Leeds. While most of the magma remains beneath the surface, in places like Erta Ale it has made its way above ground. An Ocean Without Water Scientists have also noted that the kind of magma bubbling up in the region is the type otherwise only seen spewing forth from mid-ocean ridges deep below the water's surface. One of its signature characteristics is a low proportion of silicic acid. The magma coming out of Erta Ale has the same chemical composition as the kind that emerges from deep-sea volcanoes. The entire region increasingly resembles an ocean floor -- one without water. The new burst in activity began in 2005, when a 60-kilometer-long fissure suddenly formed in the Afar Depression. Since then, roughly 3.5 cubic kilometers of magma have gushed forth, according to Tim Wright -enough to cover the entire area of London to an average person's height. From a geological perspective, the speed with which the magma is pushing forth is astonishing. It has been channeling its way through the rock below the earth's surface at speeds of up to 30 meters per minute, reports Eric Jacques from the Institute of Earth Physics of Paris. Satellite measurements attest to the consequences: In one 200-kilometer stretch welling up with magma, the ground looks like asphalt on a hot summer day. Magma is also pooling up under the Dabbahu Volcano in northern Ethiopia, Lorraine Field reported in San Francisco. Continuing to Expand Satellite data shows that a much larger area has been scarred by fissures than previously assumed, says Keir. Subterranean currents of magma are causing ground temperatures to spike in eastern Egypt, a team of geologists from Egypt's National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics recently reported in Seismological Research Letters. At the AGU conference, Columbia University's James Gaherty reported that magma eruptions have ripped a 17-kilometer gash into the desert floor in the northern part of Malawi and that the lateral pressure they have exerted has even lifted the surrounding earth up to 50 centimeters (20 inches) in places. The most violent upsurge of magma in recent years, though, happened in an unexpected place. In May 2009, a subterranean volcano erupted in Saudi Arabia. A strong earthquake with a magnitude of 5.7 accompanied by tens of thousands of milder tremors forced 30,000 to seek shelter. Magma spewed out of the ground in an area about the size of Berlin and Hamburg combined, Sigurjon Jonsson from the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology reported at the AGU meeting. The fact that the eruption took place almost 200 kilometers (124 miles) away from the fault line in North Africa "surprised all of us," says Cynthia Ebinger. And the world's largest geological construction site continues to expand. Loraine Field confirms that more and more magna is pushing its way to the earth's surface, adding that: "The magma chamber is reloading." Oxford University's David Ferguson predicts a considerable increase in volcanic eruptions and earthquakes in the region over the next decade. They will, he says, "become of increasingly large magnitude." Erta Ale, a volcano in the deserts of Ethiopia’s Afar Triangle in northeastern Africa, erupts. The volcano’s crater had always had a bubbling soup of silver-black lava. But, in November 2010, it started erupting again after decades of lying dormant. 1 of 20 Black lava bubbled up and out of the volcano’s crater on Nov. 22, 2010. 2 of 20 A shot of the volcano before the recent eruptions began. 3 of 20 The volcano’s eruption signals an increase in geological activity in Africa’s Great Rift Valley. Photo Gallery: A New Ocean Forms in Africa 01/20/2011 6 of 203 4 of 20 Indeed, Africa is starting to split apart. The first tear came in the last million years, resulting in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. And now the earth is opening up in a massive expanse of land stretching south from Ethiopia to Mozambique. 7 of 20 The magma coming out of Erta Ale has the same chemical composition as the kind that usually emerges from a deep-sea volcano. Indeed, the entire region is starting to resemble an ocean floor more and more -- just one without the water. 10 of 23 Massive fissure in the Ethiopian desert. Such fissures are normally seen on mid-ocean ridges far out at sea. 11 of 23 Similar fissures in the Afar Depression. Low hills are the only thing holding the waters of the Red Sea from rushing into the area and creating a new body of water. 12 of 23 University of Rochester / Cindy Ebinger The entire region increasingly resembles an ocean floor just waiting for the water. 14 of 23 Satellite-based radar measurements confirm the split. This one shows how the Dabbahu and Gab’ho volcanoes are growing farther apart. 15 of 23 The dusty-looking area in the upper-right-hand quadrant of this photo shows fresh volcanic ash. In recent months, geologists have discovered volcanic eruptions near the earth’s surface at 22 places in the Afar Triangle. 16 of 23 Dabbahu volcano already reach below sea level. 17 of 23 Information gathered from satellites has also shown that a much larger area within the region has been scarred by fissures than had previously been assumed. 18 of 23 Loraine Field, a scholar at the University of Bristol, confirms that more and more magna is pushing its way to the earth’s surface, adding that: “The magma chamber is reloading.” According to Tim Wright, a fellow at the University of Leeds’ School of Earth and Environment, over the last five years, the spread of the sea in northeastern Africa has been “unbelievably accelerated,” and everything is going much faster than anticipated.