Home Migration and the Saucepan

advertisement

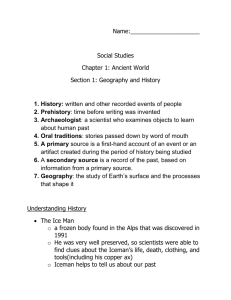

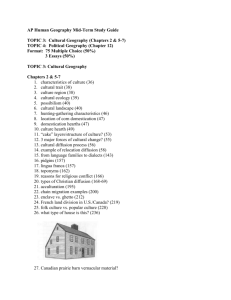

Transcript Dan Webb (DW): So I’m joined today by Katie Willis, who is a lecturer at Royal Holloway. Thank you for joining us today. Thought we’d kick off today by talking a bit about you academic background. So stretching not too far back you A-Level days, I was wondering what attracted you to studying Geography? Katie Willis (KW): I think I really got into Geography in the second year part of my secondary school, and I think it was the classic thing about trying to think about other parts of the world. I grew up in North Wales on a farm and didn’t really very far on holidays or anything like that. But I was always kind of fascinated by other parts of the world, and when we got to do A-Level Geography got to discover all these interesting things about location theory and distribution of different cultures and trying to understand global patterns of inequality and that kind of struck me as phenomenally interesting, because I’m basically quite nosey and this struck me as a really interesting way of thinking about other people and other parts of the world. I had a great Geography teacher and that was it, so I applied to university and studied Geography. DW: And what university was that? KW: So I did my Geography undergraduate degree in Oxford. And while I was there I decided that I was really fascinated by issues around development. Because I was kind of interested both sort of intellectually but also I was interested kind of politically so, this was the 1980s so politics was really important so it was like anti apartheid movement, lots of demonstrations, for all kind of different things, amnesty international, all kinds of campaigns like that. So the idea of being part of a global community, and then trying to think about understanding that from an academic point of view, but also potentially trying to do something to make the world a better place. And I decided that I would do a Masters degree in Latin American studies. DW: Why especially was Latin America a region that you were interested in? KW: I had a lot of lectures on Latin America, Latin America and the Caribbean as a student, so it might have been one of those things about serendipity that basically that was what I got exposed to. But I think it was also that idea of language. It struck me that if I learnt Spanish then I would be able to go and work in many many parts of the world. And then once I’d been to Mexico that was it. No looking back. No other region will ever compare. And I enjoyed the academic stuff so much that I stayed on and did a Doctorate. DW: And what was your Doctorate subject? KW: It was entitled ‘Women’s Employment and Social Networks in Oaxaca City Mexico’. So looking at the, the sort of the way, the work that women do, both domestically and in terms of paid work outside the home. So I was really interested in looking at women from all kinds of different groups, So from the sort of very poorest – living in shanty towns, to some upper middle class women living in very swanky accommodation and just thinking a about ok how does gender work in those different spaces? What is it that you can do as a woman if you’re rich that you can’t do as a woman if you’re poor? Or do all women experience similar kinds of disadvantage? DW: So I think it would probably be a good time to bring in the object that you choose (AHA yes!) which is going to link in to some of the things you’re been talking about already, and you choose a saucepan (I Did!) which, I guess, you cant get anymore everyday than that. And there’s probably listeners thinking, how is a saucepan in any way related to geography. So I was just wondering if you could explain why you choose it and how it relates to some of your work, and how it relates to some of the things you have been talking about? KW: Ok I was trying to think of something that would allow me to talk about a number of different aspects of both my research, and some of the wider research that has been done on, on Gender and Geography. Sort of the idea of feminist Geography. And so, the first thing I think is that the saucepan, is really that its an object that we think about in a particular place. We think about it sitting on a stove, we think about it sitting in a cupboard, in a kitchen, and being used predominately by women, so I decided I wanted to have it for the first reason because it’s kind of linked so much with the domestic space and the idea of these everyday activities to do with food production. And one of the key things that some of the early Geography and Gender Researchers did was really to say “ looking at the domestic” is perfectly legitimate and it’s really important if you want to understand how the world works. So going into the home and thinking about “what are these activities that people do within this space called the home?” So I thought the saucepan was great because it’s that kind of idea of the domestic and the kitchen and it can be viewed I suppose quite negatively in one sense because it’s kind of tying women into a domestic sphere but I thought that was a kind of well important dimension. The second reason that I chose it is because it kind of represents food, it represents some kind of idea of everyday sociability particularly between family members but maybe between a whole range of other people and some of the research that I’ve done has been on migration and thinking about people moving internationally and what that means for home. Now most of the work that I’ve done has been on expatriates moving to China. So moving from the UK or moving from Singapore to China so these are kind of privileged migrants. They’re sometimes working for some of the biggest companies in the world. They’re not refugees, they’re not fleeing persecution, but still they still have these ideas of home and they still want to kind of recreate feelings of kind of belonging and feelings of identity in the new location and one of the ways that they do this is clearly through cooking and through the way in which they set up home in their new location. So many of the people that we interviewed in China would talk so much about food and the food as the way in which made them feel, I suppose it’s kind of like medicine for their home sickness. It meant they could like feel more comfortable in this very, very unfamiliar environment. And so the saucepan kind of acts as this kind of container in which this kind of memory and these kind of feelings, a comforter are made. So that was the second reason I chose the saucepan. Final reason I chose the saucepan is I wanted to think about women’s lives outside the home and it was quite difficult to think about an object you could have inside and outside and the saucepan struck me as a great one particularly within a Latin American context because saucepans have often been used as parts of political protests by women in different parts of Latin America because they’re fantastic if you hit them with spoons or something else and the part of Mexico that I know the best in 2006 they had a very violent and disruptive period of civil unrest driven by grass roots responses to what was viewed as a very oppressive and undemocratic governor. Sometimes they would have women only demonstrations, and the women would get their saucepans, bring them out of the kitchen and bang them as they went down the street and there was this amazing sight and sound of these women who so often would get viewed as these kind of domestic restrictive individuals coming out and making all this noise and making their voices heard in this very public way. And they also set up a radio station that was called “Radio Saucepan” which was kind of the voice of opposition to kind of deal with this idea about women making a noise using these domestic objects. So I thought it was kind of a useful object. DW: Yes it’s a very interesting example of how in the global south they’ve appropriated the saucepan to use it for a completely different task. You mentioned earlier in the interview something called “feminist geographies”. I was wondering if you could expand on what that is? KW: Ok, It’s an interesting term because clearly lots of people have their own perspectives on what feminism is more broadly, but within Geography, feminist geographies the sort of fundamental was that feminist geography seeks to understand the way that the world is structured along gendered lines usually to the benefit of men although not always and to kind of seek to address those inequalities. So it has both a kind of explanatory purpose, it trying to understand the way the world works but also trying to have a purpose which means that research, teaching, any kind of endeavour should try and redress those inequalities. DW: Sounds like it’s a perspective that is very susceptible to the ‘everyday’, like looking at things like the saucepan and the house, would you say that’s particularly true? KW: I think its part of a broader kind of suite of activities that are really trying to understand these small scale ways in which people live their everyday lives and give them some value, give them value by giving them the attention they deserve. There are clearly kind of overlaps with approaches to research that have a very kind of grass roots basis and are trying to understand how people live their everyday lives, and how they talk about their every day lives and I think that while that kind of theme of research has come from lots of different directions. Feminist geography and sort of feminist researchers have had a really big impact in actually saying it’s ok to think about these very kind of what seems like very small scale activities, very kind of mundane things that we probably take for granted. It’s important to look at these everyday lives because it’s through these little practises that the world is constructed and inequalities get repeated or get challenged. Talking to some of the women who were involved in the Women and Geography study group book, which is part of the Royal Geographical society, you know they would turn up to international conferences and, you know, the men in the audience would just either laugh at them or would be really really angry because they would think this would be a really trivial or pointless exercise, talking about, you know, women going to the shops or childcare, or any of these kind of things, were all viewed as pointless, How on earth, you know, was this revolutionary? You know – why would Geographers be interested in our everyday lives? Geographers have much more important things to talk about. DW: So it’s definitely got an agenda to improve people’s lives KW: Yeah I think, I think that that what, that’s kind of what feminist geography would say that it does. Clearly every researcher will have different ideas about how that should be achieved. And then also be able to, will differ in terms of what they can actually do, because clearly not all of us are able to influence the entire universe. But it’s that kind of idea about incremental change and so on. Its kind of is similar to some of the more kind of radical approaches that came out in the 1960’s around sort of Marxist Geography. The same kind of thing about understanding some of the underlying structures which mean that the world is unequal- spatially and socially. But then trying to seek for ways that make it more equal whatever that may be depending on your perspective. DW: Brilliant – thank you very much! KW: No Problem.