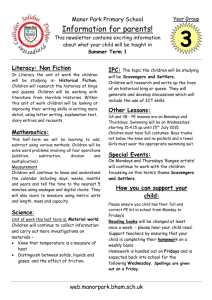

Full Text (Final Version , 381kb)

advertisement