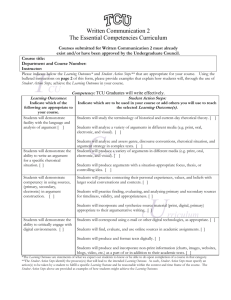

Visual Rhetoric Annotated Bibliography

advertisement

Visual Literacy and Composition: an Annotated Bibliography Fiona Harris Ramsby Bailie, Brian. “’If You Don’t Believe that You’re Doing Some Good with the Work that You Do, then You Shouldn’t Be Doing It’: An Interview with Cindy Selfe” Composition Forum 21, (Spring 2010) Web. 1 Nov.2011. Selfe is one of the premier scholars in computers and composition and someone who is absolutely committed to pedagogy. While this interview focuses primarily on techno–literacy, I think the following quote is crucial to remember whatever modality we are composing in. That is, since the “rhetorical and social turn” in composition and rhetoric, we concerned with the rhetorical choices that our students make in their compositions, that they can critical analyze the rhetorical choices of others, and understand that those choices, and their own, are shaped by hegemonies and dominant ideologies. Certainly, these choices are not always manipulative but they are never neutral. About composing in a variety of modalities, Selfe says, I think rhetoric and rhetorical understandings are themselves technologies that we can deploy when we try to make meaning in a variety of circumstances and a variety of media. But media themselves can change rhetorical approaches. Media, for example, aren’t transparent or neutral, so we need to practice with media, and we need to know the affordances and the capabilities and the tendencies and the ways in which particular media and particular modalities shape our expression, before we can be rhetorically effective. If we don’t do those things well, it doesn’t matter how important your rhetorical purpose is or how focused your rhetorical intent is or how keen your rhetorical understanding is, you have to know how to work with the tools. Unless you know something about the tool, you’re not going to be as effective in deploying the rhetorical affordances of that tool expertly. I think the two have to go hand-in-hand. So with video work in composition classes, for instance, we’re not going to teach students to be Spielbergs or anyone like that. We’re going to teach them to be good rhetoricians who can deploy any number of modes of expression and media to make meaning. We’re going to teach them to use all available means to accomplish responsible rhetorical ends. (emphasis mine) Blakesley, David and Colin Brook. “Introduction: Notes on Visual Rhetoric.” Enculturation. 3.2. (2001). Web. 26 Oct. 2001. Blakesley and Brooke introduce this issue of Enculturation to show how Visual media are being deployed in an array of disciplines, via various modalities. Taking up with W. T. Mitchell (see below), they call for a dialectical relationship between theories of text and visuals: “one in which words and images are inseparably bound in an act of symbolic interpretation and action.” They turn to the term “visual rhetoric” in order to “to understand the ways that words and images function rhetorically and together in the various forms of media and literature that grab our attention and so delicately direct the intention.” In other words, “Just as rhetoric involves more than the deployment of words and sentences in the right order, visual rhetoric involves more than just spatial arrangement or the effective use of page or screen space, font faces, headers, or visual evidence.” They thus ask for, “more intense scrutiny of how the visual functions at the point of encounter, as enabling persuasion or fostering identification, for example. How does the visual communicate meaning? Or, putting it another way, how do we interpret the visual world? Do we interpret words any differently than we do visual images? If so, what's the difference? And what's rhetorical about this process?” Overall then, Blakesley and Brooke stress the role of both the textual and visual in shaping what can be known and how it is known. (See below the Mitchell reference as to how visual representations can indicate powerful and hegemonic ideology.) For further illustration of their point, they discuss Rene Magritte’s Ceci n'est pas une pipe which complicates the way we read visuals and which highlights the sometimes problematic relationship between text and visual. Birdsell, David S. and Groarke, Leo. “Towards a Theory of Visual Argument.” Argumentation & Advocacy. 33. (1996) 1-10. Birdsell and Groarke lay down a theory of visual argument that might be useful to writing instructors in terms of analyses of visual arguments in first year writing. The authors outline their theory by way of the following: Visual arguments can be just as lucid and/or ambiguous as verbal/textual arguments. Like verbal/textual arguments, visual arguments are contextually bound. However, in this point Birdsell and Groarke provide a really useful guide to context for writing instructors. Visual arguments must be examined in terms of “immediate visual context, immediate verbal context, and visual culture.” They provide a comprehensive explanation of these “varieties” of context. Visual arguments bring up the issue of resemblance and representation. The authors pay heed to the ways in which a theory of visual arguments must account for “the disjunction between resemblance and representation, the consequent conventionalization of representation, and the susceptibility of resemblance to visual and verbal challenge.” In short, the authors insist that “we must recognize the argumentative aspects of representation and resemblance.” One must consider the difference between argument and persuasion. Some might argue that a visual cannot stand alone as argument per se, that it can be treated merely as a persuasive addition to a verbal argument. Birdsell and Groarke conclude with the following that might prove useful guidelines to writing instructors teaching visual rhetoric. They note that, “Any account of visual argumentation must identify how we can a) identify the internal elements of a visual image, b) understand the contexts in which images are interpreted, c) establish the consistency of an interpretation of the visual, and d) chart changes in visual perspectives over time. Birdsell, David S. and Groarke, Leo. “Outlines a Theory of Visual Argument.” Argumentation & Advocacy.43. (2007) 103-113. Written ten years after the above, Birdsell and Groake elaborate on their 1996 article by an explanation of the following: Modes of visual meaning: These include flags (attention getters. e.g Benetton ads); visual demonstrations (information that is best conveyed through visual means. e.g. The appearance of Victorian houses in Pacific Heights; Visual metaphors (e.g Goering as a butcher); Visual symbols (e.g The Cross for Christianity, the Union Jack for England); and Visual archetypes (e.g. people depicted with long noses, a la Pinocchio, are associated with lying). The different modes can help us determine to what extent something is “true.” Via the modes, they determine to what extent a visual argument is “propositional” (acceptable) (106). (A map, for instance, is perhaps more “truly representational” than a cartoon of Bill Clinton with a long nose.) Both make arguments but with vary degrees of pathos and logos, for instance. The authors remind us that it is important to assess to what extent images are being deliberatively deceptive in their attempts to manipulate a certain audience. To reference one of our own, Professor Jenny Andrus is writing about how photos of scenes of domestic violence serve the prosecution at the expense of a witness’s testimony. That is, the testimony is disregarded in favour of visual evidence even when that evidence does not corroborate with testimony. Useful to writing 2010 instructors, Birdsell and Groake explicitly connect their theory of visual argument to the Aristotelian appeals, particularly pathos. Pages 108-111 outline this with a discussion of various 9/11 images. “Digital Visual Literacy.” Maricopia Center for Learning and Instruction. Web. 2 Nov. 2011. Funded by a hefty National Science Foundation grant, this project and its accompanying website provide an endless amount of resources for teaching digital visual literacy: <http://mcli.maricopa.edu/dvl>. While it privileges the “how-to” rather than the theoretical implications of digital/visual literacy, the instructional modules it provides--on using visuals in word-docs and PowerPoint for example,--as well as sample assignments and rubrics provide a comprehensive resource for instructors and students learning to navigate digital and visual media. This website does not target composition classrooms per se; thus, assignments should be adapted for writing classrooms. George, Diana. “From Analysis to Design: Visual Communication in the Teaching of Writing.” CCC,54.1 (2002): 11-39.Print. George examines the use of visual literacy in the composition classroom (14 emphasis mine). She notes that in terms of pedagogy history “links words to high culture and the visual to low, words to production and images to consumption” (31). However, we must understand “how very complicated and sophisticated is visual communication to students who have grown up in what by all accounts is an aggressively visual culture” (15). We need to change our thinking. She recounts an articulate history of the use of visuals in the writing classroom, noting its status as play, and then the New London group’s call for a reexamination of the visual as more than play, as well as its urgings that multi-media relationships are dynamic. Various media should not be “read” independently but should be read to encourage multi-modal designs (17-18). She also comments on how composition scholarship has treated the visual over the last few decades; overall, she argues that composition’s de-privileging of the visual has limited the kinds of assignments we can offer in our writing classrooms. Perhaps most useful for 2010 instructors is George’s outline of what she thinks a visual argument is, (as well as her description, on page 33, of a visual argument assignment that can be adapted well into writing 2010.) Following the philosopher J Anthony Blair, she agrees that an argument “must make a claim, motivated by reasons for the claim, communicated to an audience in an attempt to convince that audience on the basis of the reasons offered” (29). George also claims that visual arguments can be evaluated in the same way “we find common for written arguments” (31): Does the visual make an argument? How well does the visual communication make that argument? Is the argument relevant to the course and to the assignment? Is it interesting? Is it clear and focused? Groarke, Leo. “Informal Logic.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 21 Mar. 2007. Web. 15 Oct. 2011.Groarke writes that “Informal logic is the attempt to develop a logic to assess, analyze, and improve ordinary language (or "everyday") reasoning.” He further states that, “Most of the work in informal logic focuses on the reasoning and argument (in the premise-conclusion sense) one finds in personal exchange, advertising, political debate, legal argument, and the social commentary that characterizes newspapers, television, the World Wide Web and other forms of mass media.” A section of Groakes article focuses on informal logic at work in visual arguments in that these arguments can convey the logical reasoning exhibited by verbal and written texts—that of premise and conclusion. He notes that given that our society is dominated by the visual, a growing body of debate is assessing whether or not visual arguments can be treated as analogous to verbal ones. Of specific interest to writing instructors perhaps, is Groarke’s explication of an advertisement for vodka. He applies the premise-conclusion formula as a method of critical analysis by breaking the ad into premise, implicit premise and conclusion components. Indeed, he notes, Insofar as the visual argument in the image can be recognized in this way as an analogue of verbal arguments, it can be understood as a visual argument which can be assessed and evaluated using the concepts and the tools of informal logic. In this way, the evaluation of the meaning of an image can be made a matter of systematic examination and critical inquiry which goes beyond aesthetic assessment. Over all, Groake concludes that by using informal logic to assess visual arguments in the same way one might assess a verbal argument, the Vodka argument is, in fact, fallacious. His example, then, offers an easy to grasp sample of how we might critically evaluate visual arguments by utilizing informal logic. Ferstle, Thomas. Assessing Visual Rhetoric. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr Müller, 2007. Ferstle collects assessment data from 7 composition first year instructors “ to uncover the actual criteria and standards valued by instructors when confronted with the complexity of new media compositions” (back matter). Three themes emerge in the first part of Ferstle’s study that might inform criteria for assessment: assessment is understood in terms of LINKAGE which consists of 1) Coherence--The relationship between image and text and whether or not it is clear; 2) Multiplicities -- how do we assess the set of modalities that exist within a composition? Or rather how do we assess the “interplay of meaning across modes” (43). Thirdly, Creativity is an important theme (which subsumes tone, style and voice)—this addresses visual conventions in terms of colour form, line, shape and texture. In terms of this theme, Ferstle seems most impressed with the instructor who demands that students analyze the social context of a picture in such a way as we analyze its meaning in the here and now (48). However, in a second round of interviews, three themes emerged: “The desire for student creativity, student critical analysis and “ a desire for… interested reading practice on the part of the instructor” (55). However, all three may be read as analogous to looking at student work through such concepts as “originality,””rhetorically astute,” “ identification,” “ in accordance with course learning” and “interesting”(56-58). In his “Discussion” (59-74) Ferstle determines three main criteria for assessment: Linkage—“The critical focus, the determining factor in the kind of assessment practice best suited for multimodal compositions” (59). Ferstle writes, “this may be understood as an attribute of a reading strategy that relates the function of the analytical frame used by the assessor to the affordances available to the modes employed in the multimodal composition” (66); Creativity—the multiplicity of meaning available to multimodal compositions (60) and Context—context appears to be measured in terms of the relationship of text and image within the composition (72) as well as the multimodal composition’s relationship to the coursework. Most interesting for instructors in Assessing Visual Rhetoric is Ferstle’s explication of interplay (66-70). Here, he recounts an analysis of Barbara Kruger’s 1982 multimodal composition Untitled: (Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face). This provides a useful set of guidelines for the analysis of a multi-modal piece. Nixon, Andrea Lisa., Heather Tompkins and Paula Lackie. Curricular Uses of Visual Materials: A Mixed-Method Institutional Study. Northfield, MN: Carleton College, Dean of the College Office, 2008. The overarching question this study asks is “Are the sources of support that the College provides well suited to the work demanded of students and faculty as they make curricular use of visual materials?”(2). The pdf of this study can be found at: <http://apps.carleton.edu/curricular/support/assets/CUVMFinal.PDF>. Most salient (for our purposes in assisting 2010 instructors) are the following: 1) Faculty members must have support to learn relevant technologies (photo-shop, video programs etc) (11). 2) Student need for accessible equipment and software, as well as instruction on how to use it (this is where easy to locate techno support in the library can be utilized) (14). 3) Criteria used to assess student work must be consistent with strategies learned in the rest of the course (17). In terms of writing 2010 then, it would be helpful for instructors to base their visual literacy assessment practices on Aristotelian rhetorical strategies— for instance, how does the image appeal to ethos, logos, pathos. How does the image project a tone etc? 4) On page 18, the authors present findings of the criteria given for composition and assessment of a presentation which utilizes power points and accompanying handouts. Criteria include: Coordination of visual with presentation and handouts, Aesthetics, Images in focus and appropriately sized, Citation of images, Pacing and coordination of presentation 5) Students stress the need for Examples of good work Portability and durability of composing software (e.g power point) (21) Support with technology and time constraints (25) 6) A further cases study suggests film analysis as a way to exemplify strategies learned in course work (27). However, due to student familiarity with writing about textual rather than visual arguments, the authors recommend a style guide or sample of the sort of work that should arise from an analysis of a visual argument (34). 7) The authors present an evaluation of and criteria for incorporating visuals into science writing (35). 8) The authors present several criteria, that emerged out of the 4 case studies, for assessment of visual arguments. These criteria overlapped across assessment practices. They are: purposeful selection of materials, aesthetics, specific and detailed analyses of visual materials in text, balance use of visual elements with the flow of the larger assignment, mechanics of working with visual materials, appropriate citation, composition. (49) The authors provide a detailed explanation of each on pages 49-51. “Introduction to the Grammar of Visual Design.” 2002 Secondary English LIG. Web. 24 Oct. 201. I found this10 page introduction to Kress and Van Leeuwen’s work on the web at <http://portals.studentnet.edu.au/literacy/uploads/grammar.pdf>. It by no means captures the complexity of their theories but is a helpful introduction to how their suggestions can be practically applied (see below for more detailed explication of their theories). They include an excellent (although much shortened) introduction to Kress and Van Leeuwen’s guidelines to reading images via Mood, Perspective, Social Distance, Lighting, Colour and Modality (modality refers to “the degree of credibility manifest in a visual image” (7)). Consequently, we may assist our students in their composition of visual arguments when we ask them to consider Mood: what “mood” are the participants in the images you select trying to convey? Perspective: are participants in a visual attempting to convey a subjective or objective stance? This is determined by high (reader in a position of power) and low (visual participant in a position of power) angles. Horizontal angles invite viewer involvement. Oblique angles prompt reflective detachment from the viewer. With “objective” images, viewers are not invited to participate per se. Instead, they must read the visual in terms of the signification of the object in the visual. Social Distance: to what level of familiarity does the image invite the reader? A close up or head shot suggests more intimate familiarity. Andie McDowell compelling us to use L’Oreal hair products, for instance. Lighting. Degree of brightness and position of light source can convey particular meanings. Shadows may indicate something secret, covered up, amiss. Bright lighting is hopeful. Soft lighting is romantic. Colour: The following table indicates the symbolic use of colour. o Blue: Peace, tranquility, truth, dignity, power, melancholy, coolness, heaviness. Regarded as being therapeutic. o Yellow: Happiness, cheerfulness. Can denote caution, decay, and sickness. o Red: Warmth, urgency, passion, heat, blood, excitement, danger and hostility. Used as an accent colour, it can promote expectations and quick decision-making. o Green: Growth, fertility, health, cheerfulness, vegetation, money. Signifies life, new growth, energy and faith. o Grey: Cool detachment, bleakness, and lack of intensity. o Purple: Wealth, royalty, sophistication, intelligence. Also the colour of passion and love. o Black: Death, rebellion, strength and evil. Associated with the supernatural, it can also suggest inner strength and determination, as well as power and formality. o White: Purity, chastity and cleanliness. o Black and white: Nostalgia, seriousness, truth, detachment. o Brown: Credibility, stability, and neutrality. o Orange: Warmth, strength of personality. Associated with autumn, it also has broad appeal. Modality: Modality pertains to the degree within which an images most naturalistically representative of the object/participants it depicts. The authors note that Kress and Van Leeuwen state that The “touchstone” in assessing modality in images is a colour photograph taken by a good photographer using a 35 mm camera in natural sunlight. This, Kress and van Leeuwen claim, is widely accepted within Western culture as being as close as a visual image will get to representing what is real in a “naturalistic” sense of how people, places and things might be depicted. (7) Kress, Gunther and Van Leeuwen. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge, 1996. This “grammar of visual design” takes a social semiotic approach to reading images. Like many grammar books however, it is significantly prescriptive. It also takes a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) approach. Meaning making is a social practice determined by context and shaped by ideological hierarchies of power. (These are not necessarily represented in the negative sense of this concept however). Representation is “a process in which the makers of signs, whether child or adult, seek to make a representation of some object or entity, whether physical or semiotic, and in which their interest in the object, at some point of making the representation is a complex one arising out of the cultural, social and physiological history of the sign maker and focused by the specific context in which the sign is produced” (6). Signs (which are read by way of metaphors) are “motivated conjunctions of signifiers (forms) and signifieds (meanings)” (7). They are never arbitrary (7). Visual design would take the following into account: 1) Communication requires maximum transparency. However, hierarchies of power should be acknowledged; this shapes how participants gain understanding. 2) Representation should be chosen in forms that sign-makers “ see as most apt and plausible in the given context…circles to stand for wheels, and wheels to stand for cars,” for example (11). What underlie this book are two important concepts that are crucial to impart to our students. They are: 1) Visual communication is always coded (32). Take a look at the stylized images of cultures, those we in our own culture cannot read, to come to terms with this. 2) “Societies tend to develop ways for talking about codes only with respect to codes that are highly valued’ (32). For example writing, is more valued that oral or visual codes. Note how science text books, for example, (see page36-8) place more importance on writing as the medium of information ,rather than the visual (as indicated by science texts books for younger children), as a child moves through her education. Kress and Van Leeuwan also look to Halliday (famous for work in systemic functional linguistics)for an overview of their system of communication. This is divided into three parts which they title “metafunctions”: 1) The ideational: Signs must reference something in the “outside world” and their relations to it 2) A semiotic must be able to project the social relations (or attitudes) between sign and receiver. Think of the difference between an image of someone looking AT the camera and someone looking away, for example. 3) “Any semiotic system has to have the capacity to form texts complexes of signs which cohere” within the text and with the context in which the text is situated (41). .Odell, Lee and Susan M. Katz “Yes, a T-Shirt!”:Assessing Visual Composition in the “Writing” Class.” CCC. 61:1 (2009): 197-216. Odell and Katz offer a set of criteria for assessing visual/textual arguments. They note that in composing and then assessing both visual and textual arguments—that is, those arguments which incorporate both--the following should be taken into account: Articulate one’s assumptions about audience and refine one’s sense of purpose; Move from given to new within individual sentences and within larger sections of text; Carefully select the amount and kinds of information to present; Convey that information in language that makes sense given one’s audience, purpose, and subject matter; Create and fulfill expectations; Learn to assess the extent to which one is achieving one’s intended purposes for an intended audience. (213-14) Odell and Katz put their guidelines to the test by assessing the composition of a T Shirt which utilizes both text and visuals to present an argument to “Visit Downtown Troy, NY” to a specific audience- the Mayor of Troy and the students of the local college. This example illustrates how their assessment guidelines might be put into practice. Consequently, this article is useful in that it clearly and succinctly collects recent discussions in assessment in visual design and rhetoric and composition and extends the outcome of these discussions to both generalizable and generative methods of assessment. “Overview: Visual Rhetoric/Visual Literacy” Writing Studio/Duke University. Web. 18 Oct. 2011. The following URL will take you to a PDF that can be handed directly to students to give them an overview of the terms “Visual Literacy and Rhetoric.” : < http://twp.duke.edu//uploads/assets/overview.pdf >. It provides the following sections for students to assess and come to terms with Visual rhetoric and literacy: 1) an introduction which offers the following succinct definitions: [Visual Rhetoric] is the use of visual images to communicate meaning. It is also important to note that visual rhetoric is not just about superior design and aesthetics. It is also about how culture and meaning are reflected, communicated, and altered by images. Visual literacy involves all the processes of knowing and responding to a visual image as well as all the thought that might go into constructing or manipulating an image. In other words, visual literacy is the ability to “read” and “write” images and the meanings those images communicate. The handout also explains how to 2) “Identify Fundamental Elements” 3) “Use Principles of Perception,” and finally it offers guidelines for 4) analyzing and “Employing Visual Metaphors” Mitchell, W.J. Thomas. What do Pictures Really Want?: the Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. In Part One, Thomas talks of images as “vital signs” and the visual’s interplay of image, desire and “surplus value.” He discusses how images evoke an array of emotions that stay with us. In Part Two, Mitchell explores how images and objects (totems for example) are “beliefs about beliefs” (162) that masquerade as objective representations when in fact they are laden with imperialism. In Part Three, Mitchell discusses Media. A medium, he writes following Raymond Williams, is a “material social practice. [It is]a set of skills, habits, techniques, tools, codes and conventions” (203). Following his definition of media, Mitchell tackles an array of media from abstract art to cyborg films with examples of his perspective and analyses. In all, Mitchell presents close readings of a huge array of images and pictures, suggesting that we must try to understand them on their own terms (think New Criticism), situate them in their historical context (think Historicism) but also to utilize them as a reading of the cultures and the ideologies within which they are situated (New Historicism). It appears that Mitchell rejects the notion that visuals can be read like texts. (See Kress, Van Leeuwen, Birdsell and Groake). A model of texuality should not be indiscriminately applied to subsume the visual. However, he worries that a fully articulated theory of the visual, to quote Blakesley (see above), “is itself overly restrictive, depending as it does upon a formalist understanding of language as a realistic mechanism of representation, as an interface or window to something else.” Redish, Janice J. “What is Information Design.” Technical Communication. 47.2 (2000):163-66. Two meanings constitute information design. 1) “The overall process of developing a successful document” and 2) “the way in which the information is presented on the screen (layout, typography, color and so forth)” (164). The design of a document must always work for its users (164)—a criteria that it is vital that we pass on to our students in terms of anticipating their audience in the design process. A designer must bear in mind: what the purpose is for designing the document, “who will use it, how they will use it and so on” (164). Redish provides an excellent and easy to navigate model of the information design process which will help writing instructors expand on these questions. Indeed, this model may help instructors guide students through the design process for visual/text documents such as flyers, posters or websites. Reddish offers further advice on info design for websites and what she terms single source: “creating a database of pieces of information …that can be used in different situations” (166). (Note* This might be useful looking ahead to Casey Boyle’s writing 2010 directorship (2013?). Indeed, Boyle encourages students to build storehouses of data from which they can pull in any given compositional situation.) Shipka, Jody. “A Multimodal Task-Based Framework for Composing.” CCC, 57.2 (2005): 277306. Print. Why, asks Shipka, stop at written/visual production in our composition classrooms? Student compositions can engage a variety of technologies (and I’m not merely referring to digital technologies). However, “increasing the range of semiotic resources with which students are allowed to compose, will not, in of itself, lead to a greater awareness of the ways systems of delivery, reception, and circulation shape (and take shape from) the means and modes of production”(278). Instead, our classrooms present the opportunity for students to “purposefully structure the delivery and reception of their [multi-modal presentations]” (279 emphasis mine). She goes on to explicate a variety of “deliveries” of student compositions—compositions that not only engage academic interaction but visceral reactions also. One such presentation on the etymology of the word “scare” not only provides an informative description of the word’s history, it was “packaged” with in an elaborate delivery system designed to viscerally heighten the audience’s reception of the word (Do look it up; it’s genius!) (279). Overall, after providing two examples of student work in a multi modal based comp class, Shipka argues that students can: Demonstrate an enhanced awareness of the affordances provided by a variety of media they employ in the service of [their] goals; Successfully engineer ways of contextualizing, structuring, and realizing the production, representation, distribution, delivery and reception of their work; Become better equipped to negotiate the range of communicative contexts they find themselves encountering both in and outside of school. (283-4) This article’s usefulness for the repurposing assignment in Writing 2010 is clear in that it demonstrates alternate ways in which we can broaden the “materials, methodologies, and technologies that students employ” in their composing processes--a broadening that goes beyond the traditional “write a four to five page essay that does X” assignment. In doing so, students can learn about the ways they can deliver, revise, re-purpose, anticipate and shape audience responses to their work (301). Multimodal composing in the composition classroom, however, must respond to the following, “in keeping with the WPA Outcomes Statement for First Year Composition” (301).For writing 2010 purposes these, of course, provide a useful source for assessment of multimodal projects. Thus, in all iterations of their compositions, students should: Focus on a purpose Respond to the needs of different audiences Respond appropriately in different rhetorical situations Use conventions of format and structure appropriate to the rhetorical situation Adopt appropriate voice, tone, and level of formality Understand how genres shape reading and writing Integrate their own ideas with those of others Understand the relationships between language, knowledge and power Understand the collaborative and social aspects of the writing process Use a variety of technologies to address a range of audiences Learn common formats for different kinds of texts Control surface features such as syntax, grammar, punctuation, and spelling. “Visual Analysis.” Writing Studio/Duke University. Web. 18 Oct. 2011. This is really useful PDF from the Duke University Writing Studio. It offers clear easy steps to analyzing visuals in a section entitled “Actions to Take.” The following URL takes you directly to the PDF which can be easily printed to handout to students: <http://twp.duke.edu/uploads/assets/visual_analysis.pdf>. UTexasSpursChannel. “Analyzing Visual Rhetoric” Youtube. Web. 25 Oct. 2011. . SPURS is a college writingpreparatory program designed to help college bound students anticipate the sort of work they will encounter in college level writing and rhetoric. This site offers introductory videos on Visual Rhetoric; The videos are taught by faculty members in the writing and rhetoric departments at UT Austin. William, Robin. The Non Designer’s Design and Type Books. 3rd ed. Berkley: Peachpit, 2008. This book is a two for one combination of typographic and design principles for the novice designer. It is highly recommended by UWP Professor, Dr Natalie Stillman Webb. This is one of the most accessible design books on the market, and it is highly recommended for students and instructors who want to supplement their writing textbook with a visual design text. In it, Williams introduces the novice designer, like many of our 2010 students, to the four basic principles of design: Contrast, Repetition, Alignment and Proximity. And yes…the acronym spells C.R.A.P.—something that delights most students. The four principles go as follows: Contrast: Williams states, “Avoid elements on the page that are merely similar…contrast is what makes a reader look at the page in the first place” (13). Repetition: She continues, “Repeat colors, shapes, textures, spatial relationships, fonts, sizes, graphic concepts, etc. This develops organization and strengthens unity” (13). Alignment: Williams states, “Nothing should be arbitrarily placed on the page. Every element should have a visual connection with another” (13). Proximity: “Items relating to each other should be grouped close together …[to] become a visual unit…This helps organize information, reduces clutter and gives the reader a clear structure” (13). Possibly the most useful section of this book, for 2010 instructors, is William’s chapter titled “Extra Tips and Tricks” (109-142). In it, she shows the novice designer how to design flyers, posters, newsletters, brochures, etc. Many 2010 students repurposing their evaluation or proposal arguments will opt to repurpose in these genres. ---. The Non-Designer’s Presentation Book: Principles for Effective Presentation Design. Berkley: Peach Pit, 2009. This book is available as an ebook through the Marriot Library. Like its predecessor, this book comes highly recommended by Dr Stillman Webb of the UWP and is extremely user friendly. It repeats much of what Williams outlines in the above entry, however, it is specifically designed for non-graphically minded, non expert presenters. So it is a terrific resource for writing students who have to make presentations in class, for example, and who want to use Power Point or some other digital medium like Open Office Impress or Google Presently