Japan in the 19th century

advertisement

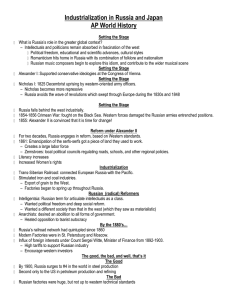

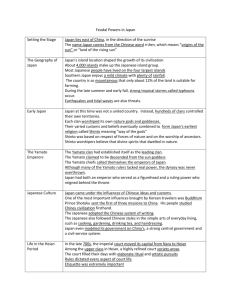

Japan in the 19th century Japan began the 19th century as it had existed for centuries; A Tokugawa Shogun ruled through a central bureaucracy tied by feudal alliances to local daimyos and samurai. Taxes were based on agriculture and the samurai were sustained by stipends paid to them by the shogunate. Culturally, Japan had two things going for it: 1. Neo-Confucianism grew among the elite (this fostered a secularism which spared Japan from the religious resistance to western based reform). 2. Japan was also homogenous ethnically. There would not be small pockets of ethnic groups pining for independence as in Russia and the Ottoman Empire. Japan’s window to Europe continued to be the port city of Nagasaki where Dutch Studies continued. Otherwise, its isolation continued until mid century. In 1853 American Matthew Perry threatened to bombard the Japanese capital if they did not open up to American trade. Japan opened itself to foreign influence and, as in China, westerners residing in Japan were not subject to Japanese laws. There was a backlash against foreigners in the 1860s. The samurai, using surplus weapons from America’s Civil War—which had just ended, defeated the shogun’s army. This delivered a clear message about the supremacy of western military technology. The Meiji seized control in 1871 and began a period of reforms that would go much further than that of Russia. The so-called Meiji Restoration included the following reforms: 1) 2) 3) 4) feudalism was abolished political power was centralized the samurai were sent abroad to learn about western science and tech the samurai were then abolished as a class although many samurai became more, some took their western learning and adopted modern political and business practices. They formed an important element of the new business class created by industrialization. The most important example was Iwasaki Yataro who founded the Mitsubishi company. 5) New nobility The government was also modernized into a centralized imperial government with limited parliamentary rule. 1) constitution created 2) New Parliament, Diet, created based on German models (The Germans gave their leader full military power and could name his ministers directly; this appealed to the Japanese). The parliament could advise government, but ultimate authority was given to the emperor. This combination gave great power to wealthy businessmen who would influence Japanese industrialization accordingly. 3) Only 5% of Japanese men had the wealth requirement to vote Thus Japan borrowed from the West but retained aspects of its own identity. Compared to Russia, Japan was better off because they incorporated business leaders into its new government structure whereas Russia could not break the hold of the traditional aristocratic elite. Industrial Revolution in Japan 1) armaments updated (modern Navy created) 2) land reform—peasants given ownership of land, Private Enterprise (Again, compare with Russia 3) agricultural taxes replaced by industrial taxes, revenues went up 4) Japan borrowed from the West but maintained close supervision on the type of reforms being admitted. They wanted to retain their own culture. Major problem with Japan’s industrialization: they had very limited natural resources and depended on foreign coal and steel. This led them to become the final great imperial nation of the 19th century. Japan would practice imperialism in Asia to gain the resources it did not have. Although it had a later start to economic and industrial modernization, Japan proved itself very quickly in two military conflicts: 1) Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) Japan defeated China in war for Korea 2) Russo-Japanese War (1904) Japan went to war with Russia over Russian eastward encroachment in Asia, particularly Manchuria and Korea. The Russian navy traveled half way around the world only to be completely crushed by the superior Japanese navy. This would, in part, lead to Revolution in Russia in 1905. Identity in Japan What is Japan? It was no longer traditional, but neither was it western. Japanese schools began to advance the idea that filial loyalty to the emperor set them apart from other nations. Thus allegiance to the emperor became an intrinsic part of Japanese nationalism. “As an antidote to social and cultural insecurity, Japanese leaders urged national loyalty and devotion to the emperor. The values of obedience and harmony, which the west lacked, would distinguish Japan from the West. This sense of nationalism would insulate Japan from the revolutions that weakened Russia, and China after 1900.” --Peter Stearns