Improving the representation of women on the TUI Executive

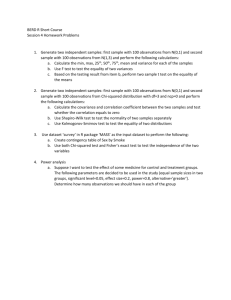

advertisement