Why is inequality called structural

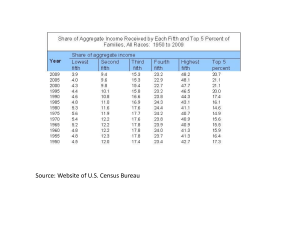

advertisement

ELC 769: Structural Inequality & Diversity March 2, 2007 Sonya Washburn Thompson Why is inequality called structural? Gross, Martin L. (1999). The Conspiracy of ignorance. New York: Harper-Collins Publishers, Inc. Gruwell, Erin (2007). Teach with your heart. New York: Broadway Books, an imprint of The Doubleday Broadway Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc. OECD (1996). The Knowledge based economy. Inequality is called structural because, wherever you have structure, systems exist. Wherever there are systems, inequality exists. For example: American public schools are designed as a system. Within the system are structures of hierarchy. Gross (1999) states at the top of American educational hierarchy that “administrators are often ridiculously overpaid and treated in godly fashion, as in the case of the chancellor of public schools in New York City, who receives $235,000 a year, more than the president of the United States” (p. 277). Gross continues to say most administrators are not knowledgeable in curriculum. Their strength is more in management and educational administration. He recommends public schools hire managers as experts over the daily routines, and have more academically educated persons as administrators. These persons would be those who studied in at least one academic area other than education. He strongly states graduates with the Ed. D. are not as qualified a candidate to be administrators as those who earn the Ph.D.. Salary structure and administrative qualifications are two examples of how inequality is called structural. Another example of why inequality is called structural concerns the need for a rise of educational training in information technology as stated in The Knowledge based economy (Organization of Economic Co-Operation and Development,1996): “Knowledge and learning. While information technologies may be moving the border between tacit and codified knowledge, they are also increasing the importance of acquiring a range of skills or types of knowledge. In the emerging information society, a large and growing proportion of the labour force is engaged in handling information as opposed to more tangible factors of production. Computer literacy and access to network facilities tend to become more important than literacy in the traditional sense. Although the knowledge-based economy is affected by the increasing use of information technologies, it is not synonymous with the information society. The knowledge-based economy is characterized by the need for continuous learning of both codified information and the competencies to use this information” (EIMS, 1994). Where is inequality? Not all public schools in America offer information technology to students. One example, Gruwell ( 2007), openly exposes public education for high school students in the late 1990’s who had little exposure to high school level reading, writing and information systems technology. Why aren’t American public schools graduating students with competencies in reading, writing, mathematics and physics? A need exists to offer more mathematics, physics, geometry and information technology curriculum beginning with middle school and high school students, in order that they will be able to compete with university students in these areas. Most graduates of American public universities are non-American citizens graduating in science, mathematics, physics and computer technology (Gross, 1999). According to the OECD, information systems knowledge is driving a new work force that can only be supported by employees knowledgeable in information technology. Structural inequalities need to be challenged. Combining industry with education provides growth of Gross Domestic Product in the major OECD economies: “Output and employment are expanding fastest in hightechnology industries, such as computers, electronics and aerospace. In the past decade, the high-technology share of OECD manufacturing production (Table 1) and exports (Figure 1) has more than doubled, to reach 20-25 per cent. Knowledge-intensive service sectors, such as education, communications and information, are growing even faster. Indeed, it is estimated that more than 50 per cent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the major OECD economies is now knowledge-based (OECD, 1996). The chart below is Table 1: Shares of high-technology industries in total manufacturing