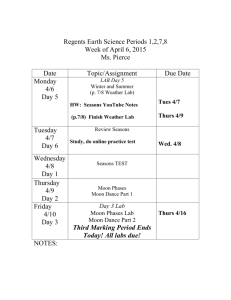

Weather Unit - University of Manitoba

advertisement