On February 9, 1950 Senator Joseph McCarthy from Wisconsin

advertisement

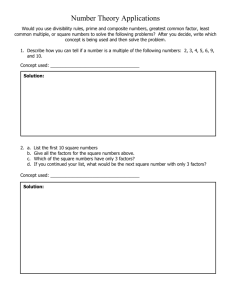

Siobhan Lehotta History 288 McCarthyism in Nebraska On February 9, 1950 Senator Joseph McCarthy from Wisconsin gave a speech at the McLure Hotel in Wheeling, West Virginia. In that speech, Senator McCarthy talked about the current Cold War involving the United States and Russia that had been rising since World War II. After briefly discussing the Cold War, he made his infamous accusation that he held a list of 205 names of people working in the State Department that were members of the Communist party. This accusation gave way to a time of confusion and fear throughout the United States, infiltrating the political views of many Americans. Throughout the mid 1900’s, Senator Joseph McCarthy and his ideas of Communism largely affected politics in Nebraska, shaping the way many Nebraskans viewed significant political ideas.1 It was during 1919 and 1920 that America encountered its first mass fear of Communism known as the Red Scare. This Red Scare was the result of increased suspicion of Communists infiltrating the United States and seizing power, similar to that of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia. Radical Americans, especially those who took part in strikes, were labeled Communists and the problems of the country were blamed on them. When the Great Depression hit the United States in 1929, it was a general consensus that loyal Americans could not be responsible. That placed the blame on the anti-capitalistic Communists. The first undisruptive out lash of blame increased, ultimately turning into blatant hunting. 2 Hunting for Communists changed into hunting for Nazis in America when Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany in 1933. Congress investigated the hunting, concluding that there should be a committee designated to investigate people and organizations that were taking part in un-American propaganda. The Omaha World Herald had done studies on Congressional spending to find that money towards investigations by numerous different offices had risen by more than one million dollars in ten years. The study noted that the Constitution does not prevent Congressional investigation, but it puts limits on the way it can be used. This act of pulling Congress into the mess is a demonstration on the power the Red Scare had on politics. In 1938, the House Committee on Un-American Activities, HUAC, was created. In 1945 Congress voted to make this committee a permanent one. It was the HUAC that gave way to many methods Senator Joseph McCarthy picked up as a Senator during Roosevelt’s Administration and would use in his hunt for Communists in America during the 1950s. 3 In August, 1948, the HUAC heard a testimony from Whittaker Chambers, Time magazine’s editor, who claimed to know eight former government officials that belonged to his cell of the Communist Party. Of the eight names given by Chambers, Alger Hiss was the most famous. An honorable man, Hiss had once worked in high positions at the State Department. Chambers was able to provide enough information to the HAUC that Hiss was found guilty of having spied for the Communists in January, 1950. Around the same time, Senator Taft suggested that the State Department had been influenced by a leftist group to give China up to Communists. With these two pieces of evidence, Americans felt that they were being betrayed and that Communists were beginning to overtake the government. It was during this second Red Scare, five years after the end of World War II, that Senator McCarthy revealed to the people in Wheeling, West Virginia that he had a list of names of people in the government who were sympathetic to or were Communists.4 When the United States joined World War II, Joseph Raymond McCarthy was young enough to serve in the armed forces, but his status as a circuit judge in Wisconsin exempted him from serving. Knowing that the military experience would boost his reputation and appeal for Senator, McCarthy decided to request a commission in the Marine Corps. He was sworn in as 2 first lieutenant. He was a captain when he became the intelligence officer for a dive-bomber squadron. As the intelligence officer, McCarthy’s job included briefing pilots before their flights, interrogating them when they returned, and preparing intelligence reports.5 During his time serving as intelligence officer in the South Pacific, McCarthy managed to suffer two accidental injuries but he transformed them into war-related injuries which could display his heroism. Besides his injuries, McCarthy was able to provide Wisconsin with photographic proof of his so-called duties abroad. Before missions, McCarthy would pose for pictures in the cockpit of planes, wearing the necessary gear of a pilot of rear gunner and eventually was able to sit in the rear gunner position during real missions. The pictures were sent to the Wisconsin newspapers where the press created the image of “Tail Gunner Joe.” 6 When McCarthy returned from war in 1945 with stories that he had never really lived through, he was easily reelected as a circuit court judge. He spent the months he served as judge planning his next Senatorial race. With his lack of legislative experience, McCarthy campaigned by spreading literature and speaking to as many people as he could. His stands on issues were weak and influenced by the people he wanted to win over. McCarthy won the primary by a slight majority but he won the Senatorial seat easily against his Democratic opponent. During his first years in Congress, Senator McCarthy took on important issues with a resiliency that helped build a reputation for himself, showing many Senators his quick wit and harsh temper that were powerful when unleashed. To build a more respectable reputation, Senator McCarthy took on an issue that was popular to many Americans as well as being a serious political issue. That issue was Communism. 7 There are several stories of how Senator McCarthy came across the issue of Communism. One story tells of a dinner party in 1950 where Senator McCarthy and friends plotted a way to 3 sweep him into an easy reelection in 1952. Anther story tells of an intelligence officer who found McCarthy after trying a few other Senators. He had disturbing information regarding Communism in America that had gone uninvestigated for two years. Whatever the story, Senator McCarthy began his crusade against Communism with a drive and commitment that many Americans had been waiting for. His enthusiasm penetrated the political opinions of many Americans, including those in Nebraska. 8 Nebraska was created in 1854 as part of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. It was officially made a state in 1867. Originally, Nebraska was a Republican state in every way. The capital was named Lincoln after the famous Republican President and Republican candidates were selected to serve the people from the local to the national level. Only a few years after it was granted statehood, Nebraska began having agricultural problems which led people away from Republican ideas and closer to Populist ideas.9 When Populism began to spread in Nebraska, both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party were forced to reevaluate their positions. By the late 1800s, the Populist Party was fading out of Nebraska as well as the rest of America. The Republican Party regained control in Nebraska but both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party had made changes to the parties that Nebraska had turned its back on just several years before.10 Both parties held strong anti-railroad and anti-corporation positions, echoing the wants of Nebraskans. Until 1920, Nebraskans would flip-flop their votes from Republican to Democratic and then back again. The parties were dealing with the growing divisions within themselves while trying to maintain control in the state by appealing to the voters.11 Throughout the 1920s, Republicans held most of the offices in Nebraska. As a whole, Nebraskans were against American involvement in European problems. Democrats had their 4 turn in congressional districts that faced agricultural problems. When the depression set in, Nebraskans turned to Democratic candidates for help. They held control of most offices until 1938 when Republicans began to revive themselves. By 1940, Republicans had regained superiority in Nebraska giving way to popularity of the new Senator, Hugh Butler.12 Hugh Butler’s first real involvement with politics came in 1929 and 1930 while he served as president of the Omaha Grain Exchange. The Omaha Grain Exchange was against the Federal Farm Board and their ideas of government regulation of grain. Gaining fame through his vocal oppositions, Butler was elected president of the Grain and Feed Dealers’ National Association in 1930. During his service to both parties, Butler’s interest in local and national issues increased. The event that cemented his interest in politics was a speech given by John B. Maling to the Omaha Rotary Club. Maling declared that socialism and communism were infiltrating every industry in Nebraska and he called for businessmen to prevent the spreading of it.13 Butler became heavily involved with the Republican Party in Nebraska after the 1932 elections. By 1936, his involvement in the party was widely known and he was elected to the position of Republican National Committeeman for Nebraska after the retirement of Charles A. McCloud. With the Party splitting, Butler worked hard to create a solid party organization while building an even better reputation.14 The 1936 elections found Butler and his Republican supporters in opposition of reelecting both President Roosevelt and Nebraskan Senator Norris. By 1938, it was clear that Nebraska was becoming more Republican. Butler felt that an anti-New Dealer might be victorious in the upcoming 1940 Senate race because Nebraskans felt the New Deal was too liberal and almost pro-Communist. After a careful evaluation of voter trends and successful 5 elimination of his highest competitors, Butler decided to announce his candidacy for the Senate on June 14, 1939.15 With five names on the Republican primary ballot, it was clear that the two front runners were Butler, backed by the conservatives, and former Governor Weaver, backed by the progressives. Both candidates supported similar ideas. Butler wanted more rights and freedoms for farmers and stressed economy in the government. He also opposed American involvement in European fights. Weaver held similar stands.16 On the local level, it was clear that Butler had organized a very successful political campaign. He organized committees and relied on key people in every part of the state with the responsibility of distributing literature and information regarding Butler’s stands. He was always careful to answer questions and write letters in an optimistic tone. His background served as a valuable tool because he appealed to many voters.17 Immediately following his election of Republican candidate for Senate, Butler began campaigning for the fall election. He used the same tactics as in the primary race. Butler appealed to the agricultural population of Nebraska, concentrating on the problems of the farmers, by introducing proposals for helping agriculture. Governor Cochran’s campaign involved the support of the New Deal’s agriculture program. Both candidates, again, were against war in Europe.18 Senator Butler was elected to the Senate in 1940 with the support of 84 out of 93 counties in Nebraska. The main reason for his election was the move of Nebraskan voters back to their traditional Republican ways. The Nebraskan Republican party was growing back together while the Democratic Party continued to split. While the trend in voting helped Senator Butler win the 6 race in 1940, his win can largely be attributed to his greatly organized campaign. Once in office, Senator Butler would remain a loyal Republican in the Senate until his death in 1954.19 While in the Senate, Senator Butler built himself a reputation as a conservative Republican who was against the New Deal and Fair Deal experimentation. It was felt by many throughout America that the New Deal was pro-Communist. Senator Butler was also against the growth of the government and believed that there needed to be economy in the government. Being from Nebraska and heavily involved in agriculture, Senator Butler was an ardent supporter of any price supports for agriculture and any programs involving irrigation. As far as his stand on foreign policy, Senator Butler was against any American involvement in European affairs except when the direct defense of the United States was vital.20 These stands remained fairly the same from the moment he became Senator until his death. He felt that the United States needed a strong defense but he opposed legislature and programs that might lead the United States to an involvement in European war. The spread of Communism needed to be stopped but without an American war in Europe. Senator Butler was also part of the Aiken Statement, which was sent to the President, suggesting that there were members of the President’s cabinet who were leading the United States to war without the consent of Congress.21 During his second term, Senator Butler began to speak out against the State Department. He felt that it was not right of our government to be fighting against Communism in a cold war with Europe while we were neglecting the Chinese Nationalists who were fighting a hot war against Communism. His disagreement with the State Department became more evident when he attacked the Secretary of State, Dean Acheson. Because he felt that Secretary Acheson was 7 prolonging peace in China, Senator Butler called for his removal from office, suggesting that Secretary Acheson might be sympathetic to the Communists in China.22 Although Senator Butler was opposed to American involvement in Korea, he was deeply disappointed when General Douglas MacArthur was removed from command by President Truman in April, 1951. He issued a statement declaring that Nebraskans were also deeply disappointed and somewhat confused with the decision. General MacArthur felt that it was important to continue the American fight against Communism while President Truman was satisfied with the stabilization of South Korea, even if that meant a stalemate. Since he was against American involvement in the first place, Senator Butler argued that the government should pull their forces completely out or let General MacArthur lead the troops to win the battle against the North Korean and Chinese Communists.23 Because of the many factors facing the United States, including the suspicions against the Russians and the fall of China to the Communists, Senator Butler was one of many people who became increasingly anti-Communist. His views, shared by many Nebraskans, led Senator Butler to support all legislature that would hurt the American Communist Party. Like many people of the time, Senator Butler supported anyone who fought Communists. His antiCommunist feelings echoed the feelings of Senator Joseph McCarthy.24 Throughout Senator McCarthy’s attacks on Communists, Senator Butler remained behind him. Although he did not necessarily agree with the way in which Senator McCarthy went about his investigations or attacks, Senator Butler agreed with the issue of investigating anyone that might demonstrate sympathy towards or support of Communists. Even when the criticism against Senator McCarthy grew, especially to the height of the investigation done against him by the Eisenhower administration, Senator Butler stayed firmly in favor of McCarthy’s 8 investigations. Senator Butler felt, like many others, that if there were people working in the government who were possibly disloyal to the United States, they needed to be found and expelled from their positions.25 Senator Butler’s anti-Communist stand was also a part of his opposition to making Hawaii a state. Senator Butler was the chairman of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, which made him the leading Republican when Hawaii’s statehood came into question. His question of Hawaii’s loyalty was initially based on its’ location. Being so close to Asia, he felt that Communist influences from China would reach Hawaii quickly. After visiting Hawaii in 1948, Senator Butler felt that Hawaii was overrun with Communism already, that the statehood of Hawaii was part of a plan coming from Moscow, and that Hawaii’s statehood should be postponed until the people of Hawaii put down the Communism which dominated the islands. Because of his loyalty to the Republican Party, Senator Butler reversed his stance on Hawaiian statehood in 1952.26 Up until his death on July 1, 1954, Senator Butler remained completely dedicated to Nebraska Republican politics. Throughout his life, he stayed close to his traditional Nebraska ways, never getting too involved with the politics in Washington unless they were of great concern to Nebraskans. After the death of his family, Butler dedicated his life to the politics he supported. Because he was never really a leader in the Senate, like his counterpart Senator Ken Wherry, his success came from the support of Nebraskans. Kenneth Spicer Wherry was born in Liberty, Nebraska on February 28, 1892. He attended public school and high school in Pawnee City, Nebraska. From there, Wherry attended the University of Nebraska where he graduated with a Bachelor of the Arts degree in 1914. After graduating from the University of Nebraska, Wherry was accepted into Harvard and took 9 courses in Business Administration for only a year. Following his courses at Harvard, Wherry returned to Pawnee City where he worked at the Wherry automotive agency. He also worked as a funeral director and a lawyer in not only Nebraska, but also Missouri, Iowa, and Kansas. When the United States got involved with World War I, Wherry enlisted in the navy but disliked boot camp, claiming that it was too slow for him. He decided to go into naval aviation only to find that he could not finish training and earn his wings before the war was over.27 After the war, Wherry returned to Nebraska and quickly earned the nickname “Lightning Ken” because of his bright personality and his ability to charm people with his public speaking. The public liked Wherry and his reputation grew quickly. He was elected city-council member and mayor. Speaking out against muddy roads landed Wherry a spot as Senator in 1929.28 After taking the spot, the Nebraska Legislature quickly named Senator Wherry a “wildeyed maverick” because he was constantly fighting for the Republican leadership. He became a close friend and follower of George Norris, the leading Nebraskan Republican of the time. Senator Wherry lost the race for governor in 1932 against George Norris and then the Republican nomination for State Senator in 1934. By this time, Wherry had made so many friends in the Republican Party that when George Norris decided to leave the party and become an Independent, Wherry was made state chairman in 1939.29 In 1940, Wherry decided to organize a political caravan, stopping at 200 towns in Nebraska. At each town, he would put on a show of debates which heightened his recognition even further. His extravagant shows brought life back to the Nebraska Republican party and Nebraskans were captivated. Republicans swept the elections of 1940, pulling Democrats out of offices throughout the state. Wherry was an exact opposite of Senator Butler, who was elected to 10 the senate in 1940 during the Republican sweep. Senator Butler had a calm control that people loved, but it was very different than the alluring appeal of “Lightning Ken” Wherry.30 In May, 1942, Senator Wherry demonstrated to Nebraska his opposition of the New Deal. He claimed that, although the programs were providing money, the programs designed for Nebraska and the Midwest were not what they seemed. Senator Wherry shared his view of the programs stating that they were not just to help Nebraskans, but to gather Democratic support and turn the people of the Midwest against their Republican views.31 Throughout his career, Senator Wherry admired, supported, and defended General Douglas MacArthur. He had been a part of the correspondence between Dr. A.L. Miller, a representative from Nebraska’s Fourth Congressional District, and General MacArthur which discussed the possibility of General MacArthur running for president. When President Truman removed General MacArthur from Pacific command, Senator Wherry challenged the President and Secretary of State, Dean Acheson. Senator Wherry never questioned the President’s right to remove General MacArthur, but he did question the reasons and judgment, hinting that the Truman Administration was hiding a pro-Communist agenda from the public.32 Senator Wherry firmly believed that General MacArthur was simply asking the American people to stand up and take a chance. He offered that America’s purpose was to fight for freedom and democracy. General MacArthur, Senator Wherry argued, was taking a risk based on America’s purpose in the world and Senator Wherry felt that Americans should be behind him. Senator Wherry felt that the risks of having to deal with the Russian Communists were far greater than taking a stand behind General MacArthur’s command.33 When Senator Wherry found out about the removal of General MacArthur, he decided to try and give General MacArthur a chance to express his views. Americans, including 11 Nebraskans, were shocked at the dismissal of General MacArthur. Introducing a resolution in the Senate, Senator Wherry wanted to give General MacArthur a time to speak his mind about his views on politics and courses in Korea and Asia in a joint session of Congress. With this resolution, Senator Wherry gained the support of many Americans who were anxious to know how General MacArthur viewed the future and any recommendations as to what should be done. MacArthur eagerly agreed to the meeting.34 When it became clear that Democrats in Congress were prolonging General MacArthur’s speech to Congress, Senator Wherry spoke to the nation on behalf of the Republicans on April 12, 1951. He questioned President Truman’s removal of General MacArthur and Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s feelings of the dealings in Korea, adding that it called for an examination of foreign policy. After hearing Senator Wherry’s speech, it was clear to President Truman that Nebraskans, led by Senator Wherry, as well as the rest of America wanted to hear what General MacArthur had to say about the situation in Asia. He allowed the Democrats to quit their stalling and let General MacArthur speak to Congress.35 General MacArthur spoke to Congress on April 19, 1951. He supported Republican thought of foreign policy in the Far East. He also suggested that Red China was acting on its own, not being controlled by Soviet Russia. In reaction to his speech, both Republicans and Democrats in the Senate introduced resolutions which called for hearings regarding the foreign policy of the Far East and Secretary Acheson’s removal from office. The Democrats, led by Senator Richard Russell, pushed for secret hearings while the Republicans, led by Senator Wherry, pushed for open hearings.36 The hearings were necessary, Senator Wherry argued, because he believed that the Truman Administration was overlooking the real problem being faced by the United Nations and 12 the United States. Without putting down Red China’s aggressive actions in Korea, Communism was sure to spread and prolong tension in the Far East. His views of foreign policy differed greatly from the powers in command.37 Communism was a hot issue, especially during the attacks on foreign policy and Secretary Acheson. Senator Wherry was one of the most passionate men when it came to removing Secretary Acheson from office because of his foreign policy. Senator called for a thorough investigation of not only Secretary Acheson but also the State Department.38 The State Department, Senator Wherry argued, had never completely answered any questions Senator Wherry asked of it. Because of their lack of response, he felt that there was a possibility that the government might be in danger of sabotage because of the possibly betrayal of the State Department. He also argued that the State Department and the Truman administration were operating in secret in regards to their foreign policy. Senator Wherry, the same as Senator Butler, felt that Secretary Acheson and the State Department were being influenced by outside sources to give up China to the Communists.39 Aside from his direct effect on politics in Nebraska, McCarthy had found a way into the lives of every Nebraskan. Nebraskans already had a fear of Soviets going into the Cold War and the age of McCarthyism. Nebraskan scientists were part of the Manhattan Project, which developed nuclear bombs, and there were atomic bombs stationed throughout Nebraska. With the beginning of the Cold War, Nebraskans were fearful of a Communist attack. It was during this fear that McCarthy introduced his Communist investigations, completely overwhelming Nebraskans.40 As a result of McCarthyism, there were several legislative bills that were introduced in Nebraska. The first three, Legislative Bill 48, Legislative Bill 49 and Legislative Bill 50, 13 pertained to the loyalty oaths made popular by President Truman. LB 48 declared that professors, instructors, and teachers at the college level needed to take the oath. LB 49 declared that all public school teachers needed to take the oath. LB 50 declared that all county and state employees needed to take the oath. All three bills were referred to a committee but withdrawn.41 Another piece of legislature in Nebraska that was a direct result of the Red Scare that was powered by Senator McCarthy was Legislative Bill 82. LB 82 required all Communists or people who worked for a Communist Front Organization in Nebraska to register as Communists with the Secretary of State. It also called for the outlaw of sabotage, requiring the terms of sabotage to be listed. LB 82 was sent to a committee and postponed indefinitely. A member of the House called for a motion which would keep LB 82 on general file but the motion failed. This failure did not keep Nebraskans from being a part of the Red Scare.42 When McCarthy had started his hunt for Communists, he helped create the second Red Scare which is nicknamed the period of McCarthyism. During the Red Scares in the United States, Americans faced numerous acts of xenophobia. College campuses were not immune to these acts. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln was one of many colleges around the United States to experiences McCarthyism first hand. Throughout the United States, everyone was on the lookout for suspicious people who could be part of a Communist plot to infiltrate America and start a revolution. At the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, several students faced investigations. After student writers for the Daily Nebraskan unintentionally criticizing Police methods, State Sheriff Endres told the Daily Nebraskan that he would be investigating the students. He claimed that the students had been active members in a Communist group at the University and that he had brought in the Federal Immigration Authorities to help investigate. The Federal Immigration Authorities reported that 14 they had found students active in Communistic meetings but could do nothing because they were U.S. citizens. Sheriff Endres claimed that the comments made by the student writers were in response to investigations being held throughout campus, hunting students linked to Communism. Dean Thompson from the University reported that although there had been investigations, no students had been “dropped from the University” as a result.43 Students were not the only targets to investigations on college campuses across the United States. At the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, professors were also under investigation for allegedly trying to organize Communistic meetings or groups. The State Commander of the American Legion at the time, Robert Armstrong, claimed that college professors were trying to recruit college undergraduates. Armstrong claimed that professors who were Communist sympathizers or linked to the Communist party were a menace. He charged that professors with that kind of link were harmful to the educational system in the United States.44 Apart from professors and students, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has also encountered anonymous acts of Communism. One morning on his rounds, a janitor found the Russian flag flying on a flag pole. The people who hung the flag had made it almost impossible to get down. The janitor called the University Police who, in turn, called the Fire Department. The flag’s strings had been cut and required a tall latter to get it down. When the flag was removed, it was kept in the University Police station. There was never any clue as to who had hung the flag.45 The reality of Senator McCarthy and his Red Scare was not fully felt until the ArmyMcCarthy hearings which lasted for about two months. In 1953, Senator McCarthy began a tirade against the United States Army. He began investigating civilians who were employed by the army and propaganda. McCarthy felt that he had found a case of espionage in an Army base 15 of Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, but the Secretary of the Army, Robert Stevens, denied any evidence of espionage. From that moment on, McCarthy was at war with United States Army. 46 Senator McCarthy went on a tear, investigating anything and anyone who seemed suspicious to him. The investigating escalated, creating a tension between McCarthy and Secretary Stevens that was seen throughout America. Republicans were frantically trying to keep McCarthy from destroying the party. The tension came to a head on March 9, 1954 when a documentary on McCarthy was aired on television. Two days later, the Army issued a report claiming that McCarthy’s investigations were really attacks and blackmail toward the “Army career of subcommittee consultant G. David Schine”. Over the course of several weeks, McCarthy’s subcommittee and the Army subcommittee battled over demands. The ArmyMcCarthy hearings began on April 22, 1954, bringing about the end of McCarthyism.47 Throughout the United States, Americans were “kept on their toes” with Senator McCarthy’s “over concerned” views on Communist infiltration. Nebraska was not immune to those concerns. Infecting the every day lives of Nebraskans, McCarthyism was able to change the political issues Nebraskans felt strongly about. With Communism as the main political issue of the mid 1900s, the government’s actions were harshly examined and the public’s ideas behind politics were changed.48 16 Notes 1 Roberta Strauss Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism: The Hate that Haunts America (St. Louis: McGrawHill Book Company, 1972), 7-9. Thomas C. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy: A Biography (Lanham, Maryland: Madison Books, 1997), 222-226. 2 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 41-53 3 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 41-53 "Investigating by the U.S. Government Has Become Big Business." Sunday World-Herald 25 March 1951. 4 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 41-53 5 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 10-18. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy, 42-54. 6 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 10-18. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy, 42-54. 7 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 19-29. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy, 54-62. 8 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 27-29. 9 Justus F. Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism (Lincoln: Nebraska State Historical Society, 1976), 1-3. 10 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 1-3. 11 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 1-3. 12 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 1-3. 13 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 6-8. "Hugh Butler."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47,56,59,60,69. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1988. 14 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 8-9. "Hugh Butler."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47,56,59,60,69. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1988. 15 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 9-12. "Hugh Butler."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47,56,59,60,69. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1988. 16 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 12-20. "Hugh Butler."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47,56,59,60,69. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1988. 17 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 12-29. "Hugh Butler."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47,56,59,60,69. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1988. 18 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 12-29. "Hugh Butler."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47,56,59,60,69. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1979, 1988. 19 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 25-29. 17 20 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 94-122. 21 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 30-44, 94-122. 22 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 30-44, 94-122. 23 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 59-76, 94-122. 24 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 59-76, 94-122. 25 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 116-122. 26 Paul, Senator Hugh Butler and Nebraska Republicanism, 116-122. 27 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 3. "Kenneth Wherry."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47, 56, 59, 66. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1985. 28 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 3. "Kenneth Wherry."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47, 56, 59, 66. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1985. 29 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 3-4. "Kenneth Wherry."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47, 56, 59, 66. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1985. 30 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 4-5. "Kenneth Wherry."Nebraska State Historical Society. 47, 56, 59, 66. 1966, 1975, 1978, 1985. 31 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 34-38. "Wherry Flays 'Perpetuation of New Deal'." Nebraska State Journal 6 May 1942. 32 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 57-78. 33 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 57-78. 34 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 57-78. 35 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 57-78. 36 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 57-78. 37 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 57-78. 38 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 112-125. 39 Stromer, The Making of a Political Leader, 112-125. 40 "The Red Menace." Nebraska Studies. 08 10 2004. Nebraska Department of Education, Nebraska State Historical Society. 22 09 2007 <http://www.nebraskastudies.org>. 41 "Legislative Bills 48, 49 and 50 ." Legislative Journal of the State of Nebraska Sixty-Second Session84-619. 42 "Legislative Bill 82." Legislative Journal of the State of Nebraska Sixty-Second Session84-619. 43 "Communist Probe Involves Students Declares Endres." Daily Nebraskan 07 April 1933. 44 "Armstrong Scores 'Reds' at University." Daily Nebraskan 09 April 1933. 18 45 "Communist Flag Flies on Campus Pole." Daily Nebraskan 07 April 1940. 46 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 114-148. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy, 505-506. 47 Feuerlicht, Joe McCarthy and McCarthyism, 114-148. Reeves, The Life and Times of Joe McCarthy, 513-526, 536-559. 48 John Drusedum, telephone interview by author, December 1, 2007. 19