The Magic Pill - Illinois College

advertisement

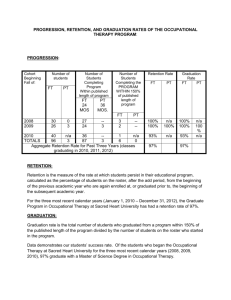

The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making Nick Capo Coordinator of Academic Advising Illinois College ncapo@ic.edu Elizabeth Tobin Dean of the College Illinois College etobin@ic.edu Abstract—Our title is only partially hyperbolical. For 2005–2006, Illinois College achieved firstyear student retention of 71.1%; for 2008–2009, our rate was 83.1%. So far, in 2009–2010, we have achieved our highest-ever fall-to-spring retention rate (95.6%) and our highest-ever sophomore retention rate (up 6.7%). We might achieve our best-ever four-year graduation rate. Because Illinois College achieved these gains with a very modest initial funding investment, we have thought about why we are succeeding. Our success resulted from a complex mixture of elements, all unified by one primary goal: improving student academic performance. Unpacking our title, we first assert the crucial importance of seven types of data (preparation data, early performance data, midterm grades, NSSE surveys, faculty advisor assessment data, retention rates, and quality-ofpersistence cohort analysis). Second, we emphasize the importance of grounding your initiatives on the strong national research. Finally, leaders within the administration and faculty must have the permission and will to implement dramatic changes to preexisting operating patterns. An institution willing to track these types of data, pursue a comprehensive strategy, change whatever interferes with student success, and reinforce promising initiatives with new funding sources, we believe, can rapidly improve student academic success and retention. I. Introduction Why is student retention such a bedeviling problem for colleges and universities in the United States? After all, we possess a higher education system that most of us are comfortable calling the best in the world. Woodrow Wilson Fellow A. Lee Fritschler, a professor at George Mason University and a former assistant secretary for postsecondary education, described our system in an address on our campus as “the envy of the world.” Fareed Zakaria, in his recent book The Post-American World, described it as “America’s best industry” (p. 190). “With 5 percent of the world’s population,” Zakaria writes, “the United States absolutely dominates higher education . . . In no other field is America’s advantage so overwhelming” (p. 190). For administrators and faculty charged with improving their institution’s retention rates, this advantage offers frequently underestimated resources. Our institutions possess one of the best-educated and hardest-working labor forces in the world. And despite the decimating financial effects of the Great Recession on higher education, most of our institutions face a certainty of existence next year and beyond that must be the envy of many for-profit organizations. Finally, we work within a social context in which most families want education for their children, despite pervasive resentment at the privilege accompanying education. Nicholas Lemann describes that context this way: Here is what American society looks like today. A thick line runs through the country, with people who have been to college on one side of it and people who haven’t on the other. This line gets brighter all the time. Whether a person is on one side of the line or the other is now more indicative of income, of attitudes, and of political behavior than any other line one might draw: region, race, age, religion, sex, class. As people plan their lives and their children’s lives, higher education is the main focus of their aspirations. (p. 6) With all of these advantages, why are our institutions often disappointed by their performance? The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 2 True, the reasons for student success and failure are varied and complex. But surely the assemblage of talent, treasure, and time possessed by our institutions should allow for the creation of conditions that enable more students to succeed, and surely spending millions of dollars on retention initiatives for relatively meager results is not necessary. Surely we can do better with no new expenditures, or perhaps modest and carefully targeted expenditures, and we can do it quickly. These two paragraphs offer a flavor of the thinking and thought-processes driving Illinois College’s Early Intervention Group, which began operating in the summer of 2006 and is our primary retention initiative. (We offer an overview of our strategy and our Early Intervention Group in our paper “Early Intervention at Illinois College: The Politics, Potentials, and Perils of Using ACT’s CollegeReadiness Benchmarks,” in the 2007 Proceedings of the National Symposium on Student Retention.) This paper is our answer to the questions about why our institution was not performing better, and it is an account of how we transformed our institution into a much stronger learning environment. Our recent outcomes convince us that we are on the right path. Back in 2005–2006, before establishing our Early Intervention Group, Illinois College achieved first-year student retention of 71.1%; for 2008–2009, our rate was 83.1%, and we currently have 84% of our first-year students preregistered for the Fall Semester of 2010. Because Illinois College achieved these gains with a very modest initial funding investment, we have thought about why we are succeeding. Our success resulted from a complex mixture of elements, all unified by one primary goal: improving student academic performance. We consciously decided to shift our faculty and staff culture away from an arguing-by-anecdote culture to a data-driven culture. We sought a shift in both the faculty/staff and student cultures. For our faculty and staff, we sought to shift the focus away from internal dynamics (“doing the best we can with the resources available” rhetoric, turf struggles, and scapegoating) by grounding our initiatives in strong national research that forced us to pay attention to what other institutions were achieving. Perhaps most importantly, we acted in substantive, and often dramatic, ways upon internal and external data. Today, in 2010, a campus consensus exists: our strategy is working, and we will stay the course. II. The Essential Data Using basic inferential statistics, we succeeded at communicating our campus reality and strategy to faculty, staff, and trustees. We rely heavily on seven types of data (preparation data, early performance data, midterm grades, NSSE surveys, faculty advisor assessment data, retention rates, and quality-ofpersistence cohort analysis). Preparation data Like other colleges and universities, we pay careful attention to a student’s high school GPA, class rank, and test scores during the admission process. But we also calculate a core academic-course GPA, based only on courses that directly correspond to our general education and major disciplines. Student A B C D E F HS Rank DNR 28% 32% 36% 80% 45% Core GPA 2.89 2.47 1.93 2.07 2.78 2.46 HS GPA 3.15 2.96 2.30 2.39 3.11 2.64 Table 1. Six Sample Core Academic GPAs for Students Considered by Committee Source: Admission Office, 2010. The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 3 This core academic GPA is a better indicator of a student’s actual potential to succeed academically in our curriculum than a GPA that includes courses we do not offer for credit. It also influences our judgment about each student’s motivation and work ethic, two traits that often correlate with academic success. We have used the core GPA in decisions to deny admission to students with classic underachieving profiles (mid-to-high twenties ACT composite with a sub 2.0 core GPA). We pay particular attention to ACT’s College Readiness Benchmarks in admission decisions, constructing students’ first-semester schedules, and constructing the Early-Intervention Group’s HighestRisk Watch List. The ACT Readiness Benchmarks are an extremely powerful tool for us because the state of Illinois requires all high-school students to take the test during their junior year and a majority of our students are Illinois residents. Our “Scheduling-to-Strengths” initiative allows our Registrar to construct pre-loaded partial schedules for each student before they meet with their pre-registration advisor during summer registration. Benchmark Math English Social Sciences Natural Sciences Number of students who did not meet the ACT readiness benchmark Year (Percentages) 22 18 21 24 2009 (n=216) 57 (26.4%) 21 (9.7%) 39 (18.1%) 81 (37.5%) 2005 (n=256) 91 (35.6%) 26 (10.2%) 68 (26.6%) 126 (49.2%) 2004 (n=258) 96 (37.2%) 23 (8.9%) 55 (21.3%) 139 (53.9%) Table 2. ACT College-Readiness Benchmarks and Academic Readiness in Core Subjects Source: ACT 2005 & 2007 and IC Registrar, 2010. Essentially we try to protect students from their high-risk courses during their first semester to reduce the transitional shock of moving from high school to college. We have, since starting this initiative in 2006, added one important refinement: once students accept our offer of admission, we ask them to select five preferred courses from a list of courses typically taken by first-year students. We try to give them several of those courses, and if we have to place them in a course for which they do not meet the readiness benchmark, we want it to be a preferred course. One benefit of this approach, to be blunt, is that it removes the pernicious effects of proper-schedule prejudices and course-headcount preservation from our scheduling process. Schedules are constructed for students and our greater interest in student success, not our lesser interests. Because many of our incoming students do not meet the benchmark in one or more areas, scheduling-to-strengths and interests allows us to reduce their risk of failure substantially. Early Performance Data On the first day of classes, the Early Intervention Group asks faculty and staff, in a message on the e-mail lists, to notify us of any student who is struggling or experiencing difficulties. This request is repeated during the opening faculty meeting. The Registrar activates online grade submission on day eleven of the semester, and encourages all faculty members to submit early midterm grades. Taken together, these measures have generated a large and continuous flow of early-performance data. During the four years our Early Intervention Group has operated, it has received between 220 and 250 early notifications during the Fall Semesters and between 80 and 140 during the Spring Semesters. Summary Date 4 February 18 February 4 March New Early Notifications 20 53 57 Table 3. Early Intervention Notifications for First Three Meetings in Spring 2010 The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 4 The participation rate among faculty averages above fifty percent, which means that although the Early Intervention Group doesn’t hear everything about every course, there are now very few surprises at midterm. During the last two years, in particular, we’ve had advance knowledge of just about every student in major academic trouble. During the crucial first six-to-eight weeks, we seek to identify as many of our struggling students as possible and to intervene to change the behaviors leading to failure. This is preemptive intrusion. Midterm Grades What comes later we refer to as “[too] late intervention,” and it is basically a process of academic triage or reality therapy. In our experience, the average eighteen-year-old student with three or four low grades at midterm rarely recovers to have a successful semester. Interventions after midterm, although necessary, are too late to ensure academic success for most students; they might prevent absolute disaster. Fall 2009 Fall 2008 Fall 2007 Fall 2006 First-Year/All Students with 1 or more D, F, and W at Midterm 68 (30.2%)/204 (22.8%) 36 (21.7%)/226 (25.1%) 113 (43.5%)/332 (32.7%) 121 (41.4%)/345 (33.7%) Table 4. Early Intervention Notifications and Midterm Grades Source: EI Group and IC Registrar 2007, 2008, and 2010. Here, we see the desired trend: the number of students with low-grades at midterm has declined. NSSE Data Our overarching goal from May 2006 can be stated this way: culture shift. To increase the amount of student success, we needed to work with tangible policies and actions as well as in the domain of intangible psychology. We needed a campus culture with more students, staff, and faculty thinking and behaving in ways more likely to lead to student academic achievement and resiliency. The problem, of course, is: How can you measure a shift in campus culture? We decided to rely on our NSSE data to identify areas to improve and to demonstrate that the invested time of faculty/staff was worth spending. Engagement Area Level of Academic Challenge Class First-Year Senior Active/Collaborative Learning First-Year Senior 42.7 50.2 46.8 53.7 44.5 51.5 Student-Faculty Interaction First-Year Senior 37.5 49.3 36.7 51.9 37.8 49.3 Enriching Education Experiences First-Year Senior 32.2 44.9 31.0 50.1 28.0 48.6 Supportive Campus Environment First-Year Senior 59.1 50.9 65.6 58.9 65.4 63.2 Table 5. NSSE Engagement Areas and Illinois College Source: Director of Institutional Research, 2010. IC NSSE 2006 IC NSSE 2007 IC NSSE 2008 52.3 53.1 53.2 55.4 58.6 57.7 The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 5 If our efforts were working, our belief was that the NSSE survey should capture the changed conditions on our campus. Looking at the five NSSE engagement areas—level of academic challenge, active/collaborative learning, student-faculty interaction, enriching education experiences, and supportive campus environment—Illinois College showed a negative significant difference from our three comparison groups in fifteen categories and a positive in only three in 2006, prior to the establishment of the Early intervention Group. In 2007, Illinois College showed a negative significant difference in only two categories and a positive in eight categories. In 2008, Illinois College showed a negative significant difference in three categories and held all of our gains compared to the Carnegie Liberal Arts colleges. Regarding academic advising, in 2008 eighty-three percent of our first-year students indicated “good” or excellent,” with those in our referent group reporting eighty-four percent and those in our Carnegie peers indicating eighty percent. Eighty-six percent of our seniors indicated “good” or “excellent,” with those in our referent group indicating eighty-three percent and those at our Carnegie peers indicating seventy-nine percent. The results in our last three administrations of the survey indicate that the academic culture at Illinois College is changing for the better. We are hoping to see a solidification and extension of these gains in our next administration (2010/2011), but we are happy with our progress. Faculty Advisor Assessment Data In December 2007, we implemented assessment of pre-major and major faculty advisors. We also created access to this data for department chairs and the RTP committee. The first assessment report to the faculty in Spring of 2010 was based on responses received during the Fall Semester and Spring Semester of the 2008–2009 year and the Fall Semester of 2009. We want to report to each faculty member at least once every two years, but we have established a minimum reporting threshold of five student responses to parallel the degree of confidentiality in the teaching evaluations. To date, we have processed 641 student responses, and generated 50 reports for individual faculty advisors. The findings are revealing the strengths of and challenges for our advisors. Accurate information about course requirements Accurate information about college services Available to answer my questions Generally responded to phone or e-mail contacts within a reasonable amount of time Generally was able to have a face-to-face conversation within a week Knows me well (interest, weak/strong subjects) Two or more productive conversations with my advisor Understand the personal benefits of a liberal-arts education Develop a specific plan for successfully completing my college experience Identify campus activities that fit my interest Obtain help from other on-campus offices Prepared in advance for my meeting with my advisor My choice of major is a good fit for my skills and interests My overall rating of my advisor is high 1.49 1.44 1.39 1.33 1.26 1.93 1.54 1.83 1.96 2.24 1.84 1.65 1.27 1.45 Table 6. Pre-Major Advising: All-College Averages for Spring 2010 Source: Office of Academic Affairs, 2010 The research we examined stressed a few key components of well-functioning advising programs: 1) a supportive relationship with a knowledgeable advisor, 2) student satisfaction with accessibility and process, and 3) joint identification of clear plans for, or “paths” to, success (Kuh, p. 1, 3). We also knew that many faculty members wanted to improve their advising, with one stating during a faculty meeting The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 6 that if the college could tell faculty what it wanted faculty advisors to do, many would be happy to do it. Therefore, we embedded our desired philosophy of advising into the assessment questions. Retention Rates Ultimately our retention efforts will be judged, both internally and externally, by our achieved outcomes, so like most institutions, we watched those numbers closely. Enrolled Start 225 F 100 M 125 10th-Day Spring 215 (95.6%) 97 (97.0%) 118 (94.4%) 10th-Day Fall [as of 9 June 2010] [189 (84%)] [88 (88.0%)] [101 (80.8%)] 2008–2009 166 F 84 M 82 158 (95.2%) 79 (94.0%) 79 (96.3%) 138 (83.1%) 68 (81.0%) 70 (85.4%) 2007–2008 260 F 126 M 134 236 (90.8%) 119 (94.4%) 117 (87.3%) 202 (77.7%) 109 (86.5%) 93 (69.4%) 2006–2007 293 F 155 M 138 275 (93.9%) 151 (97.4%) 124 (89.9%) 233 (79.5%) 133 (85.8%) 100 (72.5%) 2005–2006 256 F 117 M 139 218 (85.2%) 100 (85.5%) 118 (84.9%) 182 (71.1%) 84 (71.8%) 98 (70.5%) 2009–2010 Table 7. First-Year Student Retention: Outcomes Source: IC Registrar 2010. In recent years, we have enjoyed watching them. For 2009–2010, so far we have achieved our highest first-semester retention number (topping the previous year’s number), which was also our highest with a male-majority class, and we achieved our second-highest female retention number (just below our number in 2006–2007, EIG’s first year of operation). We also achieved our highest-ever sophomore retention and most likely will achieve our highest-ever four-year graduation number (surpassing our number in 2007–2008), and we appear finally to be making progress at closing the gender performance gap between our male and female students. Tracking this data is necessary, of course, for reporting purposes and basic accountability. But in addition, sharing it with the faculty and professional staff is equally important. The turn toward datadriven decision-making inevitably runs into opposition from what we like to call “anecdote culture,” the assumptions and remembered stories about previous periods of glory and superb students. Here is our message: For the past four years, our average retention right now is 81.1%; in the four years prior, it was 75.0%; in the first four years of our recorded data (1990-1993), it was 73.2%. So in terms of retention, Illinois College is at its best now. These signs of progress and upward trends improve morale and energize the people working daily with our current students. The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 7 Quality-of-Persistence Cohort Analysis During the Early Intervention Group’s first two years of operation, we tracked several key performance indicators for our probation and committee admits. Student academic success was our primary goal, with better retention following as a byproduct of that effort. So the quality of student persistence mattered to us (Adelman, p. -xx-), and we were happy with what we saw after the first year. Fall 12+ credits w/ ≥2.0 Year 20+ credits Registered/ Retained for 2nd Year 2006–2007 Probation Enrolled (31) Committee Admit Enrolled (42) 16 (51.6%) 34 (81%) 26 (83.9%) 38 (90.5%) 22 (71%) 34 (81%) 2005–2006 [Prior to EIG] Probation Enrolled (20) Committee Admit Enrolled (38) 3 (15%) 20 (52.6%) 10 (50%) 24 (63.2%) 10 (50%) 21 (55.3%) Table 8. Academic Performance of At-Risk Students at the End of Fall and Spring Semesters Source: IC Registrar 2010. After we abolished the “probation” category of enrollment in 2008 and in part because of time pressures and institutional software-conversion challenges, we looked less closely at these numbers and more closely at other student cohorts. Because of our general philosophy of centering our retention strategies on the academic performance of individual students, we adopted a more rigorous cohort analysis. In some ways, we now pay less attention to aggregate numbers about entire classes or the entire student body and more attention to numbers about specific smaller groups of students. This type of analysis allows us to praise high-performing areas of our college and to identify where our problems are. Here is a truncated example (omitting the female sport table and our tracking of credits and low/high GPAs) of how we monitor the performance of our athletic teams: Team Fall Roster M Swimming 6 M Tennis 6 M Golf 10 M Cross C 12 M Indoor 20 M Basketball 22 M Soccer 28 Baseball 59 Football 122 Male Student Body Average GPA Spring Roster 10 11 17 10 27 21 26 48 114 392 Fall GPA Average 3.31 NA NA 3.20 2.55 3.09 2.68 NA 2.74 Cum GPA Average 3.23 3.13 3.14 3.09 2.71 3.00 2.74 2.82 2.79 # below 2.0 0/0 --/2 --/0 1/1 4/2 1/1 6/5 --/7 18/16 # above 3.4 5/6 --/5 --/4 4/4 8/8 8/6 6/4 --/15 22/27 2.93 Table 9. Cohort Analysis: Athletics and Academic Performance in Spring 2010 Source: EI Group, Athletics, and Registrar, 2010. With the Registrar’s and Residence Life’s help, we extended this type of analysis to each floor within our residence halls, our multicultural students, our literary societies, and our TRIO-eligible students. Because of our focus on individual students (i.e., we know the names that attach to these numbers), we also can add a layer of analysis to the tables. One three-sport female athlete, for example, generated three of the The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 8 five “below 2.0s.” Out of 119 female student-athletes, only three individuals earned a GPA below 2.0. We essentially have no problem with academic performance in female athletics on our campus. III. Learning from Others We have relied upon national research for two good reasons. One, like all good academics, we wanted to use research to shape our solutions. Two, we knew that focusing on retention sometimes meets with resistance from stakeholders. Being able to cite careful and reputable research was crucial in persuading faculty to participate in our early intervention activities. Administrators also pay attention to evidence, although they are often more interested in best practices at successful institutions. Remember how Vincent Tinto (2002) put it in an AACRAO keynote speech entitled “Taking Student Retention Seriously”—if we wanted to improve our retention, we needed to “stop tinkering at the margins of institutional life and make enhancing student retention the linchpin about which [we] organized[d] [our] activities” (p. 1). At Illinois College, we were willing to make that change. We began where many other institutions have begun, with George Kuh at Indiana University. The co-authored book Student Success in College: Creating Conditions That Matter and reports about the National Survey of Student Engagement, which originated with Kuh and his collaborators, influenced our faculty a lot in thinking about pedagogy, while Kuh’s article with Gary Pike, “First- and SecondGeneration College Students: A Comparison of Their Engagement and Intellectual Development,” got us thinking about how best to encourage the thirty-five percent of our students who are first-generation to succeed in higher numbers. We took to heart his comments that policies benefitting first-generation students benefit other students as well. We didn’t expect all faculty to read all of this research, but about a third of the faculty read some Kuh at an retreat on engagement, Elizabeth Tobin spoke about Kuh’s research at a faculty conference, and we invited Jillian Kinzie to campus to speak to all faculty. We have also used ideas from Mike Rose’s writing about his own experience in California as a first-generation college student. Although Rose’s experiences are in the distant 1960’s, his memoir is articulate and relevant to the problems of our students today. He talks of not understanding the language of academia or the expected way to behave with professors. His story of sitting in his car with high school friends making fun of professors’ mannerisms has served as an example to our professors of how students’ behavior may stem less from low motivation and more from a lack of belonging. We have been influenced by the strand of research and practice which stresses that every student can learn. Their success may depend on our ability to match them with the appropriate pedagogical methods. These ideas are powerfully expressed by Freeman Hrabowski, III, President of the University of Maryland at Baltimore County, and Earnestine Baker, Executive Director of the Meyerhoff Scholars Program at UMBC. Baker’s visit to our campus inspired our intensive two-week summer-bridge program for first-generation college students. Research about programs helping students of all backgrounds succeed in science has also come from projects funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. (See the Diversity in the Sciences website at http://www.williams.edu/biology/divsciences.) We agree with the research finding that improving academic performance/experience is the best way to improve retention (Robbins, “What Works”). Therefore, we link our efforts at improving retention with conversations about pedagogy. About one-third of our faculty read articles and books about how learning communities can impact student learning; the entire faculty read at least one article on the subject. We reinforced this reading with a visit from Emily Lardner, Co-Director of the Washington Center for Improving the Quality of Undergraduate Education at The Evergreen State College. The themes of our use of national research have been first, to include detailed consideration of them in the thinking of administrators and faculty who are developing policies; second, to disseminate the ideas to our faculty more widely through targeted reading groups; and third, to describe the ideas frequently in talks and conversations on campus. This is part of the move to an evidence-based culture. The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 9 IV. Administrative Leadership of Campus-Wide Change All administrators want to increase retention. So why don’t they all put their resources and agenda-shaping abilities towards increasing retention? This is a crucial question for colleges and universities seeking to ramp up retention efforts, because the reasons for administrators’ reluctance vary with the circumstances of the institution. We tried to think about what had created reluctance in the past. At many institutions, a key issue is the limitations on a president/provost’s ability to report accurately that retention is a serious issue. That requires acknowledging to various audiences that not all college systems are successful and not all entering students are academically strong. Honesty about retention might not please donors who wonder if this institution is worth the investment, alums who may not want to see themselves reflected in entering students who need help, or parents who do not want their children to be retention statistics. Finding effective ways to talk about retention is vitally necessary. Where problems are out in the open, questions of blame are often not far behind. Colleges and universities are large virtual communities encompassing former students, often as trustees and donors, and former policy-makers, including still-present administrators and faculty. Any blame for the longterm causes of low retention lands on people who are still community members. The finger-pointing that can result from reasonable questions about how we got into this retention fix blocks support for plans to improve retention. That was certainly a feature of early efforts at Illinois College and discouraged administrative and faculty leaders from emerging. To end this paralysis, we stressed those causes of low retention created by changed circumstances, focused on our goals for the future, and deemphasized any poor decisions by existing and previous faculty and administrators. We changed the discourse. We talked about shifts in demographics, high school education, and millennial attitudes. We explicitly pointed out that the traditional lecture and the model of faculty advising have been effective in the past. Changing circumstances, however, require changing pedagogy. We used data to focus the conversation on the future. Illinois College has ambitions. We want to match our reputation to the education we think we offer students. We cannot do that without seeking to retain all of our students, not just those who behave in ways that are familiar to current faculty and administrators. Changing the discourse was the most complicated for faculty. Faculty as a group, we found, are somewhat less likely than administrators to move easily from the knowledge of who our students are to the idea that every student can learn. This can easily be read as a form of blaming faculty. At Illinois College, this conversation began badly, because many faculty saw calls for change as tantamount to saying that faculty had not done a good enough job of teaching. How can faculty be held responsible, they asked, when students behave disrespectfully or ignorantly, when they don’t seem to care or try? Some faculty argued they could teach successfully if admissions would just bring them better students. Avoiding blaming, we used three strategies to reframe the conversation. First, we used the national research to offer faculty additional ways to see unresponsive and/or unsuccessful students. They were not necessarily lazy or stupid; instead, they were Mike Rose. Second, we began to talk, with data, about who our students really are. Forty-five percent of our students are first-generation, from lowincome families, or both. Most attended high schools that did not prepare them well for college. Few came with helicopter parents. That knowledge helped our faculty discard the assumption that students were just like them. It allowed us to frame the struggle to educate our students as a part of social justice. It also freed faculty to ask for help. Finally, we offered useful help to faculty, which increased their support for our retention initiative. When a faculty member’s best efforts fail, those faculty can tap into a new structures. This strategy not only diffuses blame but also promotes creative partnerships across faculty/staff lines, and it recognizes that some students need more than one faculty member can offer. Finding a new discourse for the causes and solutions to retention was one important step. Our other significant step was creating a simple set of structures to which faculty and students can turn. Administrators can again play a significant role here, lending their decision-making power to support and finding a small amount of resources to create that structure. At Illinois College, we have found few new The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 10 resources and instead utilized existing ones. Directing those resources toward improving students’ ability to remain in college means we don’t use them for something else, say, creating an honors program or developing a center for undergraduate research. Here is a case in which our budget reflects our priorities. We have directed two course releases for one faculty member and at least one-third of the time of our one associate dean in academic affairs towards retention efforts. The fifteen-to-twenty faculty teaching in our preexisting First-Year Seminar Program have led the way in intrusive advising and acted as the first line of intervention when a student in their seminar runs into academic difficulty. The yearly workshop for the faculty teaching the seminars explicitly addresses the purposes and methods of advising. We have used the time of about twenty faculty and staff for biweekly meetings to identify struggling students and useful interveners. We ask financial aid staff and coaches to approach students if we think that relationship can be used to help a student. Finally, we use the time of the many faculty who email the associate dean and early intervention coordinator about students who miss three classes in a row, fail an exam, or miss assignment deadlines. Working on retention generally is folded into existing responsibilities. The culture change at Illinois College and new ways of talking about student success explain our ability to draw on our existing resources. Most faculty and staff have either added retention responsibilities to their job or give less attention to other responsibilities to intervene with students. The one new resource we have created is a Center for Academic Excellence, which has a fulltime director and a part-time administrative assistant. Our President chose to utilize a donor’s gift to create the Center, thereby stressing the importance of retention to the entire college community. The Center professionalizes our support for underprepared students, offering tutoring, time management, and study skills sessions. The Center is also symbiotic with our conversations about appropriate teaching, as the director of the Center helps faculty identify pedagogy to help every student learn. Even with retention widely acknowledged as a campus-wide priority, we have met with resistance. A part-time coach might too busy to respond to appeals to help with a student-athlete. Some faculty do not take the time to call in a problem. A few faculty are concerned that intrusive advising will take them beyond the academics for which they feel qualified. These problems in the life of an early intervention system are opportunities for college leadership to make a difference. The Japanese have a concept they call kaizen, which roughly translates as “change for the better through systematic study and action.” Our campus culture now includes many fans of that concept, and we have embedded it within the job description for the coordinator of academic advising and within the operating procedures of the early intervention group. The trustees have linked improvements in retention to faculty raises. The President talks about the importance of the staff role in retention at a staff conference. The dean addresses at workshops and committee meetings faculty concerns about why talking to students about their extracurricular activities supports academic success. A part-time coach’s lack of involvement in his athletes’ academic success becomes part of discussions about how to hire coaches. At all levels, our culture now manifests “positive restlessness” (Kuh et al, 2005, p. 317). V. Conclusion So what is the sum of these parts: data, national research, a new framing of the issue, administrators speaking out, and a simple set of structures? The sum for us is a changed culture. All these pieces are intertwined: data helped frame the issue; national research helped us set up our structure; administrative leadership shifted resources to retention; the discourse avoiding blame enabled faculty participation. Retention improved, and we share the praise for that success across campus. Our unassuming ingredients creating that changed culture are if not a magic pill then possibly a recipe that can be used by others. The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 11 Bibliography ACT. (2005). Crisis at the Core: Preparing All Students for College and Work. Retrieved June 27, 2007, from http://www.act.org/path/policy/pdf/crisis_report.pdf ACT. (2007). Rigor at Risk: Reaffirming Quality in the High School Core Curriculum. Retrieved June 27, 2007, from http://www.act.org/path/policy/reports/rigor.html Adelman, C. (2006). The Toolbox Revisited: Paths to Degree Completion From High School Through College. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education. Engstrom, C. & Tinto, V. (2007). Pathways to Student Success: The Impact of Learning Communities on the Success of Academically Under-Prepared College Students. Final report prepared for the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Fritschler, A. L. (2010). “Quality in the Classroom: No Child Left Behind for Higher Education?” Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellow Lecture. Illinois College. 14 April 2010. Hrabowski III, F., Maton, K., & Greif, G. (1998). Beating the Odds: Raising Academically Successful African American Males. New York: Oxford University Press. Howe, N. & Strauss W. (2003). Millennials Go to College. The American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO). Kuh, G., Kinzie J., Schuh J., Whitt E., & Associates. (2005a). Student Success in College: Creating Conditions That Matter. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Kuh, G. & Pike, G. (2005b). First- and Second-Generation College Students: A Comparison of Their Engagement and Intellectual Development. Journal of Higher Education, 76(4). Kuh, G. (2006). Thinking DEEPly about Academic Advising and Student Engagement. Academic Advising Today, 29(2), 1, 3. Kuh, G. (2008). High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter. AAC&U’s Liberal Education and America’s Promise (LEAP). Lardner, E., Keast, H., Williamson, B., Hamilton, C., Reis, J., van Slyck, P., et al. (2005). Diversity, Educational Equity, and Learning Communities. Olympia, WA: The Evergreen State College, Washington Center for Improving the Quality of Undergraduate Education. Lardner, E., & Malnarich, G. (2008). Sustaining Learning Communities: Moving from Curricular to Educational Reform. Perspectives. Lemann, N. (2000). The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Robbins, S. (2007). “What Works in Promoting Student Success.” Conference Proceedings of the National Symposium on Student Retention, 24 Sept.–26 Sept. 2007, The University of Oklahoma Center for Institutional Data Exchange and Analysis. The “Magic Pill”: Data-driven Decision-Making 12 Rose, M. (2005). Lives on the Boundary: A Moving Account of the Struggles and Achievements of America's Educationally Underprepared (c1989). New York: Penguin. Smith, B. L., Macgregor, J., Matthews, R., & Gabelnick, F. (2004). Learning Communities: Reforming Undergraduate Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Spears, K., Arnold, J. D., et al. (2003). Learning Communities in Liberal Arts Colleges. Olympia, WA: Washington Center for Improving the Quality of Undergraduate Education. Tinto, V. (2002, April 15). Taking Student Retention Seriously: Rethinking the First Year of College. AACRAO Keynote Speech, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Retrieved June 27, 2007, from http://soeweb.syr.edu/academics/grad/higher_education/vtinto.cfm Zakaria, F. (2008). The Post-American World. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.