weaving 19th

advertisement

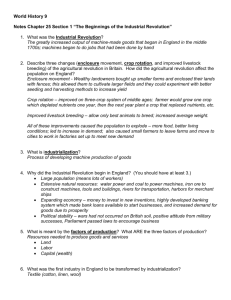

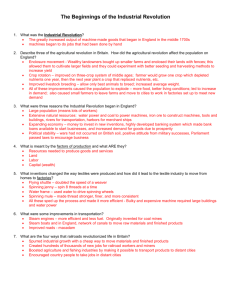

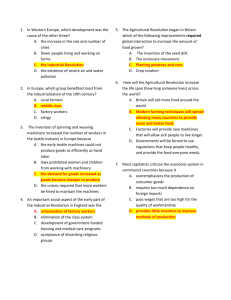

Mr. Kunkel’s World History Survival Packet The Industrial Revolution “One of my primary objects is to form the tools so the tools themselves shall fashion the work and give to every part its just proportion.”-- Eli Whitney Student Name _____________________________ Date _____________ Period _______ 1 History of the Industrial Revolution Introduction and Overview The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and transport had a profound effect on the socioeconomic and cultural conditions starting in the United Kingdom, then subsequently spreading throughout Europe, North America, and eventually the world. The onset of the Industrial Revolution marked a major turning point in human history; almost every aspect of daily life was eventually influenced in some way. Starting in the later part of the 18th century there began a transition in parts of Great Britain's previously manual labour and draft-animal–based economy towards machine-based manufacturing. It started with the mechanization of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. The introduction of steam power fuelled primarily by coal, wider utilization of water wheels and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity. The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world, a process that continues as industrialization. The impact of this change on society was enormous. The first Industrial Revolution, which began in the 18th century, merged into the Second Industrial Revolution around 1850, when technological and economic progress gained momentum with the development of steampowered ships, railways, and later in the 19th century with the internal combustion engine and electrical power generation. Historians agree that the Industrial Revolution was one of the most important events in history. Changes That Led to the Revolution The most important of the changes that brought about the Industrial Revolution were (1) the invention of machines to do the work of hand tools; (2) the use of steam, and later of other kinds of power, in place of the muscles of human beings and of animals; and (3) the adoption of the factory system. The children of the poor would have little or no schooling and would work from dawn to dark on the farm or in the home. Before machines were invented, work by children as well as by adults was needed in order to provide enough food, clothing, and shelter for all. The Industrial Revolution came gradually. It happened in a short span of time, however, when measured against the centuries people had worked entirely by hand. This relatively sudden change in the way people live deserves to be called a revolution. The Industrial Revolution grew more powerful each year as new inventions and manufacturing processes added to the efficiency of machines and increased productivity. Indeed, since World War I the mechanization of industry has increased so enormously that another revolution in production is taking place Organizing Production Several systems of making goods had grown up by the time of the Industrial Revolution. In country districts families produced most of the food, clothing, and other articles they used, as they had done for centuries. In the cities merchandise was made in shops much like those of the medieval craftsmen, and manufacturing was strictly regulated by the guilds and by the government. The goods made in these shops, though of high quality, were limited and costly. The merchants needed cheaper items, as well as larger quantities, for their growing trade. As early as the 15th century they already had begun to go outside the cities, beyond the reach of the hampering regulations, and to establish another system of producing goods. From Cottage Industry to Factory Cloth merchants, for instance, would buy raw wool from the sheep owners, have it spun into yarn by farmers' wives, and take it to country weavers to be made into textiles. The merchants would then collect the cloth and give it out again to finishers and dyers. Thus they controlled clothmaking from start to finish. Similar methods 2 of organizing and controlling the process of manufacture came to prevail in other industries, such as the nail, cutlery, and leather goods. This system of industry had several advantages over older systems. It gave the merchant a large supply of manufactured articles at a low price. It also enabled him to order the particular kinds of items that he needed for his markets. It provided employment for every member of a craft worker's family and gave jobs to skilled workers who had no capital to start businesses for themselves. A few merchants who had enough capital had gone a step further. They brought workers together under one roof and supplied them with spinning wheels and looms or with the implements of other trades. These establishments were factories, though they bear slight resemblance to the factories of today. Why the Revolution Began in England English merchants were leaders in developing a commerce which increased the demand for more goods. The expansion in trade had made it possible to accumulate capital to use in industry. A cheaper system of production had grown up which was largely free from regulation. There also were new ideas in England which aided the movement. One of these was the growing interest in scientific investigation and invention. Another was the doctrine of laissez-faire, or letting business alone. The three most important machines that ushered in the Industrial Revolution were: the crude, slow-moving steam engine built by Thomas Newcomen (1705) The second was John Kay's flying shuttle (1733). It enabled one person to handle a wide loom more rapidly than two persons could operate it before. The third was a frame for spinning cotton thread with rollers. This invention was not commercially practical, but it was the first step toward solving the problem of machine spinning. Inventions in Textile Industry As the flying shuttle sped up weaving, the demand for cotton yarn increased. Many inventors set to work to improve the spinning wheel. James Hargreaves, a weaver who was also a carpenter, patented his spinning jenny in 1770. It enabled one worker to run eight spindles instead of one. About the same time Richard Arkwright developed his water frame, a machine for spinning with rollers operated by water power. In 1779 Samuel Crompton, a spinner, combined Hargreaves' jenny and Arkwright's roller frame into a spinning machine, called a mule. It produced thread of greater fineness and strength than the jenny or the roller frame. Since the roller frame and the mule were large and heavy, it became the practice to install them in mills, where they could be run by water power. They were tended by women and children. These improvements in spinning machinery called for further improvements in weaving. In 1785 Edmund Cartwright patented a power loom. In spite of the need for it, weaving machinery came into use very slowly. First, many improvements had to be made before the loom was satisfactory. Second, the hand weavers violently opposed its adoption because it threw many of them out of work. Those who got jobs in the factories were obliged to take the same pay as unskilled workers. Thus they rioted, smashed the machines, and tried to prevent their use. The power loom was only coming into wide operation in the cotton industry by 1813. It did not completely replace the hand loom in weaving cotton until 1850 Many other machines contributed to the progress of the textile industry. In 1793 the available supply of cotton was increased by Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin. Watt's Steam Engine While textile machinery was developing, progress was being made in other directions. In 1763 James Watt, a Scottish mechanic, was asked to repair a model of a Newcomen steam engine. He saw how crude and inefficient it was and by a series of improvements made it a practical device for running machinery. Wheels turned by running water had been the chief source of power for the early factories. These were necessarily situated on swift-running streams. When the steam engine became efficient, it was possible to locate factories in more convenient places. Coal and Iron The first users of steam engines were the coal and iron industries. They were destined to be basic industries in 3 the new age of machinery. As early as 1720 many steam engines were in operation. In coal mines they pumped out the water which usually flooded the deep shafts. In the iron industry they pumped water to create the draft in blast furnaces. The iron industry benefited also from other early inventions of the 18th century. Iron was scarce and costly, and production was falling off because England's forests could not supply enough charcoal for smelting the ore. Changing Conditions in England The new methods increased the amount of goods produced and decreased the cost. The worker at a machine with 100 spindles on it could spin 100 threads of cotton more rapidly than 100 workers could on the old spinning wheels. Southern planters in the United States were able to meet the increased demand for raw cotton because they were using the cotton gin. This machine could do the job of 50 men in cleaning cotton. Similar improvements were being made in other lines of industry With English factories calling for supplies, such as American cotton, and sending goods to all parts of the world, better transportation was needed. The roads of England were wretchedly poor and often impassable. Packhorses and wagons crawled along them, carrying small loads. Such slow and inadequate transportation kept the cost of goods high. Building Canals and Railways Many canals were dug. They connected the main rivers and so furnished a network of waterways for transporting coal and other heavy goods. A canal boat held much more than a wagon. It moved smoothly if slowly over the water, with a single horse hitched to the towline. In some places, where it was impossible to dig canals and where heavy loads of coal had to be hauled, mine owners laid down wooden or iron rails. Early in the 19th century came George Stephenson's locomotive and Robert Fulton's steamboat, an American invention. They marked the beginning of modern transportation on land and sea. Railroads called for the production of more goods, for they put factory-made products within reach of many more people at prices they could afford to pay. The Condition of Labor As conditions in industry changed, social and political conditions changed with them. Farm laborers and artisans flocked to the manufacturing centers and became industrial workers. Cities grew rapidly, and the percentage of farmers in the total population declined. The population of England as a whole began to increase rapidly after the middle of the 18th century. Because of progress in medical knowledge and sanitation, fewer people died in infancy or childhood and the average length of life increased. Machines took a great burden of hard work from the muscles of human beings. Some of the other changes, however, were not so welcome. The change from domestic industry to the factory system meant a loss of independence to the worker. The home laborer could work whenever he pleased. Although the need for money often drove him to toil long hours, he could vary the monotony of his task by digging or planting his garden patch. When he became a factory employee, he not only had to work long hours, but he had to leave his little farm. He lived near the factory, often in a crowded slum district. He was forced to work continuously at the pace set by the machine. The long hours and the monotonous toil were an especially great hardship for the women and children. Problems of Capital and Labor A person had to have a lot of capital to buy machines and open a factory. Laissez-faire was the rule in England. This meant that the government had accepted the doctrine that it should keep hands off business. Factory owners could therefore arrange working conditions in whatever way they pleased. Grave problems arose for the workers--problems of working hours, wages, unemployment, accidents, employment of women and children, and housing conditions. Children could tend most of the machines as well as older persons could, and they could be hired for less pay. Great numbers of them were worked form 12 to 14 hours a day under terrible conditions. 4 Child Labor The Industrial Revolution led to a population increase, but the chance of surviving childhood did not improve throughout the industrial revolution (although infant mortality rates were reduced markedly). There was still limited opportunity for education, and children were expected to work. Employers could pay a child less than an adult even though their productivity was comparable; there was no need for strength to operate an industrial machine, and since the industrial system was completely new there were no experienced adult laborers. This made child labour the labour of choice for manufacturing in the early phases of the Industrial Revolution between the 18th and 19th centuries In 1833 and 1844, the first general laws against child labour, the Factory Acts, were passed in England: Children younger than nine were not allowed to work, children were not permitted to work at night, and the work day of youth under the age of 18 was limited to twelve hours. Factory inspectors supervised the execution of the law. About ten years later, the employment of children and women in mining was forbidden. These laws decreased the number of child laborers; however, child labour remained in Europe and the United States up to the 20th century. By 1900, there were 1.7 million child laborers reported in American industry under the age of fifteen. Women During the Industrial Revolution Women faced different demands during the industrial age to those that they face today. Women of the working classes would usually be expected to go out to work, often in the mills or mines. As with the children and men the hours were long and conditions were hard. Some examples of work specifically done by Women can be found amongst the links at the foot of this page. Those who were fortunate may have become maids for wealthier families, others may have worked as governesses for rich children. The less fortunate may have been forced to work in shocking conditions during the day and then have to return home to conduct the households’ domestic needs (Washing, Cooking and looking after children etc.) Women also faced the added burden of societies demand for children. The industrial age led to a rapid increase in birth rates which clearly has an impact upon the physical strength of the mothers. It was not uncommon for families to have more than 10 children as a result of this demand: and the woman would often have to work right up to and straight after the day of the child’s birth for financial reasons, leaving the care of the new born child to older relatives. Migration Millions of people moved during the industrial revolution. Some simply moved from a village to a town in the hope of finding work while others moved from one country to another in search of a better way of life. Some migrants had no choice in the matter, they were 'transported'. Transportation was a punishment. Britain had for a long time sent convicts to her colonies, a practice that had appeared to be in turmoil after the Americans won their independence (The British used the American Colonies as a place to send criminals). Migration was not just people moving out of the country, it also involved a lot of people moving into Britain. In the 1840's Ireland suffered a terrible famine. Faced with a massive cost of feeding the starving population many local landowners paid for laborers to emigrate (it was cheaper than paying them poor relief for a long period of time). About a million of these laborers migrated to Britain, many others moved to North America. Disease and Deprivation Disease was a constant threat during the Industrial Revolution. Changes in the way that people lived and the conditions in which they worked led to disease being able to spread much more rapidly, and new forms of disease emerged that were as deadly as any killer that had been before. As the demand for housing increased so rapidly the quality of homes constructed was low. Housing for the worker was cramped in, built quickly and built with little regard for hygiene. In many cities the result was that large slums appeared. These slums were areas where houses were small, roads narrow and services such as rubbish collection, sewage works and basic washing facilities nonexistent. In this type of climate bacteria’s 5 grow quickly, the water supply is likely to become infected and weaker people are likely to fall ill much more rapidly. Water was often the problem. Factories would dump waste into streams and rivers. The same streams and rivers were used to supply homes with water for washing and cooking. Soon people’s health was endangered. In many slums the same water supply was infected with human sewage as toilet facilities were often inadequate. Cholera was a deadly disease was water borne and spread through filthy cities with ease, killing thousands. Typhoid also took a hold in some areas and again made great use of the poor sewage provisions to take a hold of many areas. In an age where the ordinary man had no political say however, and no money or even education to support a claim for improved conditions, the issue was often overlooked. These diseases rarely concerned the wealthy, there was always another worker available to replace those who died, so why should they concern themselves with issues such as the health of the poor? The Industrial age also saw the advent of new forms of science and medical advances, these too aided the fight against killers such as Cholera and Typhoid. Rise of Labor Unions Workers sought to win improved conditions and wages through labor unions. These unions often started as "friendly societies" that collected dues from workers and extended aid during illness or unemployment. Soon, however, they became organizations for winning improvements by collective bargaining and strikes. Industrial workers also sought to benefit themselves by political action. They fought such legislation as the English laws of 1799 and 1800 forbidding labor organizations. They campaigned to secure laws which would help them. The struggle by workers to win the right to vote and to extend their political power was one of the major factors in the spread of democracy during the 19th century. Revolution Spreads to the United States. Farming and trading were its chief interests until the Civil War. Labor was scarce because men continued to push westward, clearing the forests and establishing themselves on the land. A start in manufacturing was made in New England in 1790 by Samuel Slater. He was hired by Moses Brown of Providence, R. I., to build a mill on the Pawtucket, River. English laws forbade export of either the new machinery or plans for making it. Slater designed the machine from memory and built a mill which started operation in 1790. Pioneer Industries and Inventions New England soon developed an important textile industry. It had swift streams for power and a humid climate, which kept cotton and wool fibers in condition for spinning and weaving. In Pennsylvania iron for machines, tools, and guns was smelted in stone furnaces. They burned charcoal, plentiful in this forested land. Spinning machines driven by steam were operating in New York by 1810. The first practical power loom was installed at Waltham, Mass., by Francis Cabot Lowell in 1814. Shoemaking was organized into a factory system of production in Massachusetts in the early 19th century. New England was the first area in the United States to industrialize. American inventors produced many new machines that could be applied to industry as well as to agriculture. Cyrus McCormick invented several machines used to mechanize farming. His mechanical reaper revolutionized harvesting, making it quicker and easier. Elias Howe's sewing machine eased the life of the housewife and made the manufacture of clothing less expensive. Techniques of factory production were refined in American workshops. Eli Whitney led the movement to standardize parts used in manufacture. They became interchangeable, enabling unskilled workers to assemble products from boxes of parts quickly. American factories used machine tools to make parts. These machines were arranged in lines for more efficient production. This was called the "American system of manufacturing," and it was admired by all other industrial nations. It was first applied to the manufacture of firearms and later spread to other industries like clock and lock making. 6