Breathlessness – a Patient Perspective

Chris Warburton

An address given at the Breathlessness National Symposium

on Tuesday 1 July 2014, organised by NHS Improving Quality

“I’m going to die! I can’t go on trying to breathe!” I desperately yell, or perhaps whisper.

“My diaphragm is so sore! I’m tired!” And I give up.

“Do you want to … …”

But by then I’m gone.

I find myself in perhaps a hospital bed, bars at the side, something just vaguely familiar;

oops and then I’m off again … and again ... and again. Then I see vague shapes and they talk

to me but I’ve no idea what they are asking or telling me. They don’t understand what I’m

saying – possibly the words don’t seem to come out right. Finally I whisper something that

my daughter, who suddenly appears out of the misty blur, seems to understand. She sticks my

specs on my nose and all comes into focus. Yes – I am in a hospital ward – like last time – but

why in Wales?? She tells me that I have been in hospital for four or five weeks and we are not

in Wales ... … OMG … … too much to deal with … so back to the fairies!

Now that was just six months ago and I am very fortunate to have completely recovered. That

episode of respiratory failure, treated initially by non-invasive respiratory support and then to

ITU for ventilation and support, is the penultimate stage in breathlessness: the topic that we

are all here to talk about today. The ultimate would be death.

My name is Chris WARBURTON and I am in my 70th year. Thank you, Chair, for inviting

me to speak at the Breathlessness National Symposium. I feel very honoured to be your

keynote speaker. I was touched when Vanessa Brown, our organiser, mailed me and said

“The reason the [your] session is first, is to remind those in the room why we are all here, so

your input is vital.”

Just to put what I have to say into a context I will give you a bit of background … …

I have smoked millions of fags, well I think about a million and a half in 45 years. (I know

HCP’s work it out differently in units that make no sense to us patients.) I stopped some eight

years ago. So I have severe COPD – finally diagnosed also about eight years ago as well as

bronchiectasis.

I have several co-morbidities, too. I am an eight-year survivor of prostate cancer. I have

suffered from diverticulitis and IBS for years. A “stationary” kidney stone is being watched

and I have a hernia (caused by the coughing) that needs fixing. I am just trying to work up the

courage to go back into hospital. Two or three other conditions also exist that tend to make

life a bit uncomfortable.

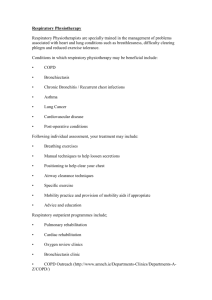

I have done Pulmonary Rehabilitation three times during the last six years and I currently

attend a weekly exercise maintenance class. I utilise ambulant oxygen and I get quite a lot of

drugs prescribed to take in various ways.

On the positive side I have a great group of HCP’s around to help me. But I do have to attend

four different hospitals. I am a real fan of OUR NHS. The respiratory ward in my local

hospital is, I feel, outstanding. They also run the exercise maintenance class that I attend

whenever I am fit enough. I have a sympathetic GP practice. My Borough (very fortunately)

runs a domiciliary respiratory care service which I believe is being “integrated” with the

hospital service. So I have an allocated respiratory physiotherapist who not only comes and

sees me but is available by email and phone, often with an immediate response. Now that is

incredibly supportive to me and my family.

I do have to say right now how well supported I am by my family as well: my wife is my

carer, and then there are my daughter, my sister and the relatives. I am well known in my

local community with many friends and acquaintances – all very enabling.

So that is enough about me.

Please remember that this talk is only about my personal experience of breathlessness within

the context of serious COPD – I have a lung function of about 33%. I know that there are

other causes of breathlessness but I can only tell you of my personal experience.

As long as it works, we all take breathing for granted. I think it is hard to imagine what

breathlessness really feels like. My wife reminded me I had explained it like this to her: “I am

aware now of every breath I take” – and I would now add a rider “but also of its own

quality”. To be quite frank, I am only comfortable when I am lying down or sitting down

doing nothing physical. So it is no wonder that patients suffering from breathlessness can

easily become inactive and seat-ridden, unfulfilled and depressed.

So if you remember this: COPD really stands for

CAN ONLY PLAN DAILY

The behaviour of your COPD patients becomes a whole lot clearer.

Within the context of my own COPD, the level of breathlessness is very variable which can

be intensely frustrating. For example, for no apparent reason I can wake up, medicate and

find that even walking the five steps to the loo is a great effort that leaves me wobbly,

breathless and tired out. The next day it’ll be easy peasy … or not … or something in

between. Whilst weather seems to play a part in this (I seem to remember there was a trial of

a special weather forecast for us a few years ago), I am clear it is multifactorial. And this is

just normality for me before we even think about the trials and tribulations of exacerbations.

It is hard enough for us to manage in my semi-retired state, but I think this must be terribly

hard for fellow sufferers who are still in full time employment.

The important concept to understand is we are constrained in every sphere of life. The

simplest every day act can be a trial. Showering and washing my hair exhausts me – even

with a sneaky faceful of oxygen when I get out, that’s followed by dressing – which is not

much fun either and I do not want to be in leisure wear all day long.

2

We are fortunate enough to live in a pleasant three story Edwardian house in North London –

but it is on a hill, and the slightest slope is anathema to me with no breath. It’s also built as

six half floors and a cellar. There is no loo on the ground floor. This gets a bit more difficult

when my gut problems flare up, or when I am taking prednisolone, a mighty effective drug

for opening up my chest. Unfortunately it carries a massive load of nasty side-effects

including an increase in “urgency” similar to when my prostate was in full spate. The myriad

stairs at home, whilst my physio tells me it’s good for me and keeps me fit, can tire me out –

even when using oxygen.

Bending down for whatever reason has me breathing very hard very quickly.

Again, too much effort when I am trying to cook (which I really enjoy) leaves me slow and

feeble. Our kitchen is not particularly ergonomic so I have to move around a lot and that

means running out of breath. I can’t use my oxygen when I have the burners on the hob

alight.

Also, I soon learnt that it is false economy, so to speak, not to get my breath back properly

before I carry on. I have to operate in my own time and others around me just have to respect

that. I think you need confidence to demand that.

The best way I can describe it to people is by saying that I have enough oxygen just to sit/lie

down and do nothing physical except talk and eat perhaps, and that there is no oxygen

reservoir in any of our lungs, just what I carry on my back. This is especially true,

incidentally, when walking. Easy for me to say – not so easy to actually do, especially if

those around you do not understand and have little sympathy for your condition.

But OK, all these and every other aspect of life are now just normal day-to-day inhibitions on

my life at home, where we control the environment. What happens when I go out?? It took

me a while to get a grip on this. And it still frightens me. Why?

Easy – when you think about it – I am NOT in control.

I get anxious, nervous, have we got everything sorted? Just to get today organised means

probably an exchange of a dozen or so mails, for example. And that is with some very helpful

staff.

How are we going to get there? Have we ordered the cab? Or what’s the parking like and

how far from the front door? Chest tightening …

Where’s the meeting – are we on the stage? How many steps? Are there mikes? Who’s

looking after us? Shaking inside …

How much oxygen do I have? It’s heavy to lug around. Where are the loos? What’s the traffic

going to be like? Where are my inhalers?

And I get worried about it. Never used to. I sit down. Do my breathing exercises. Pursed lips.

My chest is tight, really tight. Resist the urge to have a suck at my salbutamol … go quiet: go

calm: five minutes to departure … but a further mini panic as I slide into the car.

Once we’re on the move I feel I can relax again, because I am back in control of my little

universe, making our way through London’s traffic in my space. Phew … and that is when

things are running relatively OK.

3

I’m not even going to share with you the negative influences of my co-morbidities on these

trips.

So what happens when it all starts to go wrong? I think everyone who is breathless should be

taught (on a one-to-one basis if necessary) pursed lip breathing and deep breathing

techniques. And when to use them. They talk about this on the PR courses. They try to give

you coping strategies. But I like to get things done and fixed, sorted. So I get a bit impatient.

I’ve overdone it a few times and got really frightened and panicky. I did discover, however,

that a squirt of salbutamol generally got me out of those situations although it was really hard

– I do always carry an inhaler with me, as we were advised. I thought these were the panic

attacks people talked about. I was rather puzzled that what I had experienced seemed a bit

mild as to what a few colleagues had mentioned.

Then recently I happened to hear an account by actor Rebecca Front (aka T/V’s Barbara

Wintergreen in The Day Today) on Radio 4 from her latest book Curious – True Stories and

Loose Connections. She recounts her experiences of panic attacks on train rides, flights and

tunnels caused by claustrophobia. For our purposes, what causes it is not the point. It is the

flavour of the horrific experience that she catches:

“I’ll describe the symptoms: hot flushes, cold shivers, racing pulse, the

inability to breathe, the feeling you want to run away but you can’t move a

muscle, nausea, dizziness … that’ll do for starters. And it all comes over you

in a wave in a matter of seconds, sometimes completely out of the blue …

And here’s the thing: once you’ve had one, the feeling is so overwhelmingly

grim that you’ll go to almost any lengths never to have one again.”

So never, ever minimise the effect of panic attacks. They are horrific. And I am so so grateful

that I do not get them … I guess it’s also highly problematic how to treat them.

That’s the dramatic effect when things go wrong – but breathlessness also has a permanent,

long term depressive effect on us and our loved ones. Dreams have to be ditched. You must

remember that we have suffered a loss – a great loss. There are things we have had to reduce

doing or even give up. We’re never really sure we’re going to get to any date we set up. For

us, it is really sad that I can not go to the States anymore where we have many friends and

relatives, for example.

Losses mean depression, sadness and resentment. And that leads to rejection, isolation and

unhappiness. But help is at hand from many providers. Do not forget the British Lung

Foundation has a helpline open to patients, carers and HCP’s as well as local Breathe Easy

groups over the country offering support.

So I do hope I have given you fresh insights into the lives of some of your breathless patients.

And perhaps a deeper understanding as to why we are like we are.

Chris Warburton

London 1 July 2014

© 2014 Chris Warburton All rights reserved

email: chris@working.co.uk

phones 020 8292 8898 (h) 07973 256123 (m)

4