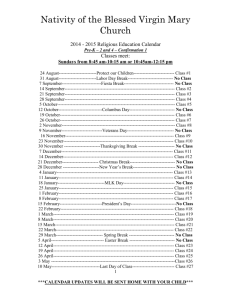

Case Study Of Calendar Use

advertisement

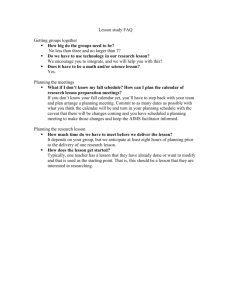

Look Three Times: Feature Constellations Based on Activity Patterns and Incentive Differences Jonathan Grudin Microsoft Research One Microsoft Way Redmond, WA 98052-6399 USA +1 425 706 0784 jgrudin@microsoft.com “Like most phenomena—atoms, ants, and stars—characteristics of organizations appear to fall into natural clusters, or configurations.” — Henry Mintzberg, A Typology of Organizational Structure ABSTRACT The challenge of designing the best overall interface while supporting individual differences has long been with us. As software is used ever more widely, one might think the problem would grow, but in fact it could become more tractable. Wide use enables us to identify and understand patterns of preferences, and greater interaction among users may contribute to coalescing usage into a few widelyshared constellations of features. Field studies indicate that applications that are widely used in organizations have different patterns of use resulting from different activity and incentive patterns: one for individual contributors, one for managers and their staff, and one for executives and their assistants. When designing, acquiring, or supporting such applications, the best approach could be to literally treat it as being different applications. In several cases, failure to consider these three categories of users led to avoidable problems and lost opportunities. Keywords requirements analysis, design, acquisition, deployment, support, training, individual differences, personas, roles, scenarios, organizational behavior INTRODUCTION This paper draws on observations of practices in several major international organizations that are producers or sophisticated users of technology. These organizations have experts in technology design and use who contribute regularly to CHI and related conferences. Yet in requirements gathering, design, deployment, and/or support, each failed to anticipate the impact of new technologies due to not understanding that different constellations of features are used by different people. Most significantly, the different patterns of use are surprisingly systematic, almost predictable once we shift from a broad view of individual differences to a narrower focus on organizational behavior. Individual differences have been important considerations since software became affordable enough to consider accommodating them in design. Nevertheless, designers (and users) generally feel that individual differences are not handled well. It is difficult for designers to get their arms around the problem, and difficult for users to exploit customization or tailoring features. In this paper I propose that for people working in organizational contexts, forces are pushing a user of widely-used applications in organizations into one of three patterns of behavior. The best approach for those designing, developing, acquiring, deploying, or supporting an application is to assume that they are designing, developing, acquiring, deploying, or supporting not one but three applications. Otherwise, they are more likely to make mistakes and miss opportunities. Individual differences exist at all levels of software use. We differ in motor skill, perception, cognition, social interaction, and cultural norms. We have different experience, knowledge, and aesthetic preferences. Within organizations, the focus of this paper, we have different roles and ways of working, different corporate cultures and professional domains. Motor or perceptual differences that an individual cannot work around, such as color blindness, must be addressed directly. Domain differences are addressed by third parties that tailor systems to particular vertical markets. Other individual differences have proven more elusive, and small wonder: The set of all possible variations is immense. Often, attention is limited to the experiential distinction: “beginner-expert” or “user-IT professional.” This distinction is necessary but insufficient. Designers strive to do more. Efforts to include every feature conceivably useful to anyone result in complex interfaces and charges of ‘bloat.’ Providing choices in menus labeled options, preferences, customize, settings, controls and so forth runs afoul of two unpleasant facts: Architecturally it has proven difficult to organize these in a logical way, and people don’t customize their interfaces. Mackay [5] noted that people rarely customize software. When they do, it is usually upon first use. At that point they have little idea how they will use the software when experienced, so they are ill-prepared to customize it well. Nor do they try: Most customization is an effort to recreate a previous interface, not to exploit new possibilities. When people have enough experience to benefit from customizing, inertia has set in: They have found satisfactory ways of using the software. Customization is easier now than in 1990, but rates remain low (McClintock, 2001, personal communication). With users not customizing, designers strive for a single acceptable default interface, even when they know that this is not ideal. Adaptive interfaces are one approach to addressing the situation, interfaces that take the initiative and customize themselves [e.g., 1]. Progress has been slow since the AI efforts of the early 1980s; trials have found some admirers and perhaps more detractors. A new generation of work in this area is emphasizing the crucial role of human-computer interfaces [e.g., 4]. A second approach, also originating in AI efforts of the early 1980s, is to identify a manageable set of user types and find a design or designs that work for them. This has evolved into current work on workflow systems. In organizations, people have different roles, and it seems logical to tailor interfaces according to their role. Efforts to do so over the past 15 years have had limited success. Problems include the effort of setting up and maintaining the identification, the fact that people may shift roles from time to time (as well as more permanently), and that access privileges and other features are often based not only on role but also on experience, level of trust, and so forth. In addition, formal representations of work process that accompany and motivate the assignment of roles often turn out to be overly constraining. Outside organizational settings, this focus is represented by interest in ‘personas,’ which are often applied to consumer as well as organizational settings. Especially to the degree that they are informed by data about real people and their work habits, these can be useful guides to design and development teams. Unlike workflow systems, they do not lead to formal representations in software. The approach described here differs from these. It is confined here to technology use in organizational settings, and focuses not on job titles or roles, but rather on the activity patterns of people. Activity patterns correlate with roles, but are much more general. And with support from organizational theory as well as empirical data, we can posit that there are only three to five basic activity patterns to consider, and they appear in all organizations. This is tremendously helpful, as the possible number of roles and personas is virtually unlimited. The argument that will be made is that differences based on activity patterns to a very large degree overwhelm other individual differences, and that this is increasingly true and will become even more true. Thus, if you are designing, acquiring, deploying, or supporting software that will be widely used in an organization, you will benefit from considering people from at least three categories, and if you do not consider them you are likely to get unwelcome surprises. Hence, the recommendation to think of it as three different applications, one in each context. If your software is targeted at just one category, it remains useful to think carefully about the activity patterns of the targeted group. The next section is a detailed example from a case study of shared calendar use at a large organization. Henry Mintzberg’s five-fold typology of organizations and their parts is introduced. Its usefulness as a tool for organizing and understanding observations of technology use is illustrated through several examples, including a reanalysis of two published case studies. I then describe why it is likely that the activity patterns described here will be even more compelling guides to design and use in the future. CASE STUDY OF CALENDAR USE Over a three-month period I observed and conducted interviews of on-line calendar use at Castle (not real name), a large corporation employing tens of thousands who work at sites around the United States and internationally. Castle employees had been using and sharing calendars for many years. Initially online calendars were used primarily by managers and the office administrators (‘admins’) who worked with them. Executives had long shown ambivalence toward widespread email and calendar use by individual contributors, but in the late 1990s developed a vision of the company’s future that relied heavily on digital technology. This required universal access, and individuals were adopting email and calendars at a rapid pace. Historically, different calendars had been favored at different times. Due to this history and the lack of platform interoperability, Castle had 7 software calendars with 1000 or more registered users. IBM Profs was used most widely, others included Digital All-in-1, Lotus Organizer, Schedule+, Calendar Manager. At the time of my visit Castle was planning to standardize on Exchange and Schedule+ company-wide. They were beginning a trial rollout of Schedule+ and were interested in understanding current practices with a view to smoothing the transition. The 20 interviews lasted over an hour apiece on average. Those interviewed were at different sites; they included engineers and other individual contributors, admins, managers, a director, and staff involved with training in general and the early rollout in particular. The interviews covered the history of online calendar use by the individual. Several of the employees had recently shifted to the use of Schedule+; those interviews also covered their initial reactions. In addition, many employees had in the past experienced more than one on-line calendar and thus had other bases for comparing features. Finally, difficulties with the current system rollout were identified. Patterns emerged from the analysis of the interviews. Experiences reported by engineers and other individual contributors differed in key respects from those reported by managers and the admins who work with them. Additional differences came from the executives and executive secretaries; although only one Director and one executive secretary were interviewed, interviews of the staff handling the rollout of Schedule+ uncovered their experiences handling the needs of executives. Finally, as I conducted this study, Leysia Palen [9] completed an extensive quantitative and qualitative study of calendar use at two other companies, Sun Microsystems and Microsoft. This involved approximately 100 interviews and a detailed survey of approximately 2500 employees partially reported in Grudin and Palen [2]. The discussion that follows draws on their data as well as the interviews. Feature use by individual contributors For fluency individual contributors, employees to whom no one reports, are referred to as ‘individuals.’ (Of course everyone is an individual and at times works on individual tasks. The thesis here is that managers and executives are affected by their schedules, work patterns, and incentives whatever they may be doing at a given moment.) Individual contributors often work at their desks and attend relatively few meetings. On-line calendars were less appealing, sacrificing the portability and versatility of paper calendars for little gain. Many began using online calendars when meeting reminders appeared [2,9]. With few meetings, it was easy to forget that one was happening. Features that beep or pop up visible reminders are popular with this group. Another feature that attracted individuals to online calendars was its integration with email. Meeting templates or invitations that can be dropped into an online calendar are constant reminders that life could be easier than writing details into paper calendars. Printing, on the other hand, is something individuals rarely do. They have few meetings and many of those are regularly scheduled. Most recent online calendars allow users to control how much calendar information they share, both globally and on a meeting-by-meeting or person-by-person basis. Individual contributors who have had no experience with calendars are likely to have some concerns about ‘micro-management’ should all of their calendar information be visible to others. They are generally very comfortable showing ‘free-busy’ time, what times they are and are not available, but not the specifics of their meetings and appointments: who it is with, where it is, what the topic is, relevant attachments, and so forth. Feature use by managers and their admins One admin had recently begun using Schedule+. Early in the interview she asked if there was a way I could get a request back to its developers. I did not work for Microsoft at the time of this study but asked “What message would you like to get to them.” She told me that there was a feature that was completely useless and terribly frustrating: meeting reminders. The two managers she worked with, and she herself, knew their calendars inside out and had no need to be reminded. But Schedule+ was being rolled out with a default of setting a reminder for regularly scheduled meetings, and she did not know how to turn it off. This illustrates two points. One is the radically different value attached to this feature by people with different roles in the organization. The second is that this was not recognized by the team rolling out Schedule+; individual contributors themselves, they set defaults based on their own use of the application. The managers she worked with, like many managers, printed their calendars frequently, often two or three times in a day. Schedule+ came with several print format options, understanding them was important to admins. Most admins received some training on Exchange and Schedule+ during the rollout. One said that she had learned some things, but hadn’t felt it was really designed for her. And it wasn’t, discussing meeting reminders more than printing, for example. Because admins spend a lot of time maintaining calendars, the ease of dragging or dropping or clicking on invitations, in contrast to retyping meeting information from an email or phone message, was considerable. It was more than an invitation to use online calendar; for some it was a crusade to convince everyone to use meeting invitations. The biggest surprise to me was the attitude toward open sharing of calendar information at Castle. Managers and admins found it extremely useful to share calendar details with one another. They could use the information in myriad ways: to learn where someone would be after a meeting ended, when they might be interrupted, where a meeting was being held, who needed to be involved, and an endless number of ways, including ingenious approaches to solving problems efficiently or learning about the organization. In fact, open sharing of calendar information was so useful to managers and admins that it greatly reduced the risk of micromanagement or other abuse: It could lead to a discontinuation of accurate calendar maintenance, eliminating the benefit. Individuals came to see this as well, and about 90% of Castle employees had fully open calendars, marking as confidential the occasional private meeting. Feature use by executives and executive secretaries An executive secretary confided that she was on a personal campaign to stamp out the use of a calendar feature that she considered an abomination: meeting invitations! The very feature beloved to some of the admins she worked with. Why? In the past, the executive would ask her to schedule meetings that came to him in email, and she would have a chance to point out concerns about agreeing to that meeting at that time and place. Now the executive was all too likely to accept the meeting himself, reducing her involvement and possibly requiring her to cancel it, which is trickier than declining in the first place. It was quite clear that admins and this executive secretary were at loggerheads, but they did not fully understand why. Early in the rollout, the transition team considered the issue of writing or contracting conversion software, for example to convert Profs calendars to Schedule+ calendars. They decided it was too difficult, that people would have to retype their calendar content. They had not recognized that although this was only a few minutes work for them, executives had densely-packed calendars scheduled out for months and even years. It might take an executive secretary a week to rekey all of that information. The rollout team was forced to reconsider the decision to get conversion software. Executives relied even more heavily on printed calendars. Unlike most managers, some of them had calendars typed for them prior to online calendars. They were extremely attached to familiar formats. Schedule+ only supported about seven different print formats. The leader of the rollout team told me that the single most unanticipated problem was the incredible fussiness of upper management about print formats. (He himself never printed his calendar.) It was a major problem, eventually solved by contracting with Microsoft to develop a couple dozen special print formats for use within Castle. The only people interviewed at Castle who did not work with open calendars were the executive secretary and the Director. At this level in the organization, who is meeting with whom and about what is much more sensitive. Executives typically don’t even allow access to their freebusy information. This reticence of executives is also found at Sun, where employees also default to open sharing of calendar information [9]. people rarely customize. It does not reflect the fact that certain sets of features naturally go together. The oversight extends in Castle to the requirements analysis process. People are often consulted, but all preferences are merged and some are deemed essential and others dispensable. “It may turn out that the resulting set of features isn’t usable by anyone,” one employee observed. In the next section, I review an analysis of organizational behavior that helps support, explain and extend these observations. This framework is then applied to observations from several other organizations. 1. Individual contributors — Live at desks, reminders popular — Meeting invitations an incentive to use — Printing unimportant — Privacy can be a concern, often unwarranted 2. Managers and ‘office administrators’ — “Live from calendars,” reminders unnecessary — Meeting invitations very useful — Printing important — Benefits of very open sharing far outweigh privacy 3. Executives — Live on the road, schedule far in advance — Meeting invitations dangerous — Printing very important — Privacy very important Figure 1. Calendar use: constellations of features. Constellations of features A TYPOLOGY OF ORGANIZATIONAL FORMS Figure 1 summarizes points drawn from the experience at Castle and supported by Palen’s data from Sun. Much of this is also found in Palen’s study of Microsoft, except that open sharing of calendar information is not widespread perhaps for historical reasons. (Some at Microsoft who do share calendar information are impressed with the efficiencies that result.) Henry Mintzberg [7] outlines a typology of organizations that is on very detailed, but tractable. It is not focused on technology use in organizations but may be a useful tool in exploring and understanding technology adoption and use. The typology is accompanied by some organizational theory. This section is a summary of the cited book chapter, which itself is a summary of a book. In hindsight these data make sense. People in these different roles have different activity structures, different demands on their times, different sensitivities concerning their meetings, difference incentives. It makes sense that different sets of features support people in different roles. Mintzberg describes 5 “natural clusters or configurations” into which organizational characteristics fall. He begins by identifying 5 basic parts of most organizations, illustrated in Figure 2. The operating core consists of the individuals who produce the organizations products and services, the strategic apex are the executives or top management, and the middle line consists of all managers in a direct line between them. To the side are the technostructure, referring to those who design and define the organizations work processes and standards, and the support staff, which encompasses everyone else, possibly including mailroom, cafeteria, library, public relations, and legal staff. This pattern has not been recognized by designers, by those rolling out the software, creating the training, and so forth. The one size fits all approach is taken to setting installation defaults, training, documentation, FAQ lists, and so on. The software supports customizing many of the features, but Strategic Apex Technostructure Support Staff Middle Line Operating Core Figure 2. Parts of an organization. (After Mintzberg, 1984.) Mintzberg contends that these five parts often vie for influence. Based on the nature of the work, the competitive environment, or other factors, one of the five usually has particularly strong influence. Thus, there are five basic types of organization, each manifesting the ascendancy of one segment of the organization. In a start-up company, the founders or executives—strategic apex—have considerable influence. In a university, the professors and lecturers— operating core—have unusual influence, and so on. There are also five basic ways to coordinate work, each corresponding to one type of organization: Direct supervision of work, standardization of work processes (as on an assembly line), standardization of outputs (as in piecework), standardization of skills (through diplomas or accreditation), and mutual adjustment. Depending on which part of the organization is dominant— that is, which type of organization is being considered, a different way to coordinate work is emphasized. For example, management — middle line — favors standardization of output, retaining flexibility for each division or department to formulate its work processes. If the technostructure is ascendant, standardization of work processes is the focus, and so on. This is a partial sketch of Mintzberg’s detailed and logically compelling description. To what degree organizations are pushed toward one of five configurations, as Mintzberg claims, or to what extent hybrids or other variants occur, is not clear. Nevertheless, the typology provides a useful way to think about an organization. A key point to bear in mind is that each of the five parts of an organization can have very different outlooks, biases, ways of working, priorities, incentives, and so forth. If true, it is no surprise that people in different part of an organization will react to a technology differently. It makes perfect sense to consult them independently when gathering requirements, when designing and testing a system, when planning a rollout, when setting up support. As the case study of shared calendars illustrates, this is not done. It is not often done at any step of the process. Confusion, backtracking, resistance, miscommunication, and lost opportunities occur throughout because of the failure to recognize and take into consideration these differences. In the case of shared calendars, it is clear that differences in patterns of activity contribute to the constellations of features that members of different parts of an organization find useful. Whether people have many meetings or few, whether their meetings are politically sensitive or not, these shape the use of the technology. Mintzberg focuses more on differences in attitudes and incentives in different parts of an organization. These two are likely to shape the response to technology. Markus and others [3,6] have noted that technology adoption can shift power balances. One can methodically set about trying to identify all stakeholders when a major system is being introduced, but it is trickier when an application that could be used by everyone is being considered. If everyone is a potential stakeholder, where do we start? Mintzberg provides an answer: Start by reflecting on the affects of the software from the perspective of the major parts of the organization. HOW MANY PARTS TO CONSIDER? The Castle description covered three of Mintzberg’s five parts of the organization. Should we expect to see three patterns of application use, or are more likely? For any given organization this is ultimately an interesting question that can only be answered by investigating. Key factors are likely to be the activity patterns surrounding the use of the technology by different parts of the organization, differences in incentives among them, and also the number and influence of people in a given part. The activity pattern, the structure of people’s days, may be similar across groups. People working in support or technostructure roles may have similar patterns to those in the central parts. Managers in all areas attend many meetings, individuals may work primarily at their desks. Barring differences in incentive structures, we would expect behavior to be covered by the three designs. On the other hand, as Mintzberg suggests, there can be different incentive structures, and perhaps activity patterns, based on organizational part. In the next section I present several examples of widely-used applications that are received differently in different organization parts, including one in which the reward system of mobile individual contributors in the support staff is different than that of individual contributors in the operating core, resulting in use of technology that falls into a very different pattern. The three organizational parts in the main line are common and critical in most organizations, so it is safe to begin with those three in considering a design or a product. Careful study could find that a fourth or fifth pattern exists. Nevertheless those currently designing, acquiring, and supporting applications typically think in terms of only one pattern of use, so three would be a major advance, not difficult to achieve. EXAMPLES Email In a 1989 paper based on ethnographic studies, Perin [10] described differences between individual contributors and managers in the use of email in the mid-1980s. The asynchronous, interrupt-driven nature of email was a positive feature for individual contributors. Not so for many managers. With their time often solidly booked into meetings, already feeling over-burdened with interruptions, many managers did not relish yet another channel of interruption. Some managers at the time printed out email, placed it in a folder corresponding to the sender, and reviewed it shortly before their next meeting with the person. Another advantage of email for individuals is that as a relatively informal medium, one in which the recipient can choose if and when to examine it and whether or not to respond or even acknowledge reading it, it was a more permissible channel for circumventing hierarchical communication paths. It was more like a conversation in the elevator than a formally scheduled meeting. This advantage for individuals was a disadvantage for the manager being circumvented. Rumor-propagation, generally enjoyed by individuals, could be a problem for managers. So could the converse: A manager placing a spin on a communication received from above by email (in contrast to verbally) risked having the spin revealed if the original email spread. Perin described managers who felt strongly threatened by email. Email use spread from the bottom up. Managerial acceptance grew appreciably when features useful to managers, such as document attachments and calendar integration, became prevalent. Application sharing NetMeeting, a free software application supporting application-sharing, chat, shared whiteboard, and point-topoint audio and video, was released in the mid-1990s. In 1998 I participated in a study of NetMeeting deployment in a large organization, where it was used by individuals, managers, and executives. It was evident that NetMeeting was designed for individual contributors and as a result missed a range of opportunities. In this organization, managers and project leaders used NetMeeting to conduct distributed meetings. To use the conference server to set up meetings, a group was supposed to have several sites, and they usually did. The audio, limited to connecting only two sites, could not be used, so speakerphone conference calls were used. After the initial use of the software by one group, the manager who led the meeting was furious. The open floor control feature was an abomination, she said, included only because a developer had found a way to do it. In her meeting, people had intentionally or accidentally wrested control from her and one another. Chaos often reigned in large meetings, with people accidentally sharing out their email and so on. However, open floor control is ideal for two or three individuals sharing an object. In the same vein, NetMeeting did not provide tools that would be very useful to managers: agenda tools, action item tools, brainstorming tools. In one meeting, a group kludged a brainstorming tool: Everyone typed their ideas into the chat window, which one person then copied into a notepad and from there into Word, where he deleted the names one line at a time to get the desired list. In the course of my observations, a team of NetMeeting developers visited to observe its use in this organization. They had never seen it used by more than three people at a time. (They also noted that the ad hoc brainstorming tool would be more efficient if the list were copied into a spreadsheet: the column of names could be deleted as a whole.) NetMeeting 3.0 subsequently supported multiple floor control models, but not the other tools. An opportunity was missed: Thirty years of research into meeting support software was neglected because the product was designed for only one category, individuals. Lotus Notes Orlikowski [8] describes the early use of Lotus Notes in a consulting company. The partners saw the benefits of using it to share knowledge and experiences, cutting down on duplication and increasing efficiency and profits. The individual contributors, the consultants, had no incentive to learn the system. Even worse, the environment was extremely competitive among consultants, some of whom would be promoted and some let go, and their value was in their experience and knowledge. Sharing it with their colleague-competitors was not a priority. This unanticipated executive-individual difference was very expensive to the company. Careful thought to the organizational parts could help anticipate the potential problem and lead to the creation of incentives to learn the system and share knowledge, something that rivals of this company subsequently did. There is a further twist. The company was deploying thousands of copies of Notes around the world and a support team handled installation and training. Support team members are not in the competitive “up-or-out” battle to become partners. Ironically, they used Notes discussions to share best practices in the fashion envisioned for the consultants. In this case, a fourth of Mintzberg’s organizational parts came into play. The incentive structures and activity patterns of the technical support group plausibly coincided with other support staff distributed around the field offices of the company. Many would be engaged in noncompetitive tasks similar to those at other branch offices. Thus, Notes could be especially good tool for this category. More calendars In the late 1990s, a team highly experienced designers and developers, including two solid contributors to the HCI literature, developed a set of office applications to run on a ‘network computer.’ The intent was to create streamlined, useful, usable, core-functionality email, calendaring, and other productivity tools for transaction processors. The team had difficulty identifying workers dedicated to transaction processing, and eventually prepared to deploy the applications widely in their own organization, first to individual contributors, then to managers and executives. (Sources: email and conversations with the design team and Leysia Palen.) When managers began using the calendar, the team had to deal with a show-stopping problem. The reducedfunctionality calendar has no printing capability. Managers, recall, print calendars; individuals rarely do. The calendar had been designed by and for individuals and had to be reengineered to include printing. Another problem cropped up when executives began using the calendar. In this company, as in Castle, open calendar use is the default – almost all individuals and managers allow others to access calendar information unless an item is explicitly made private. As at Castle, executives are the exception. The reduced-functionality calendar did not allow one to block off the entire calendar, one had to make appointments private one at a time. This was unacceptable to executives and executive secretaries, who insisted on another reengineering of the product. A general phenomenon Upon consideration, what initially seemed surprising comes to seem inevitable. People with different demands on their time and attention find different application features useful or find different ways to use the same features. One cannot be certain and must still conduct an investigation, but a sensible hypothesis is that a widely-used application will find three or four distinct patterns of use, constellations of features, sets of preferred practices. Even setting aside considerations of use by IT professionals, it will likely need three requirements gathering exercises, three regimens of usability testing, three training programs, three FAQs. PRESSURES OF INTERACTION Why hasn’t this been noticed before? For several reasons, all pointing to this being an emerging phenomenon. Only recently have many managers and executives become computer users, and they are only gradually expanding their use of software. The key change, however, is that software use has become much more collaborative. The examples described above -email, shared calendars, Lotus Notes, NetMeeting – support communication, collaboration, and coordination. Collaborative software use leads to greater conformity in behavior within a group in three ways. First, to be most effective, many group support technologies must be used by all group members. As a result, considerable (if sometimes subtle) peer pressure is exerted to bring one’s peers on board [2]. Then, once the application is being used by a group, people discover the features that others find useful by seeing and discussing them. Finally, to work effectively, people establish shared social conventions and patterns of use. In this way, if a feature or way of using it fit with one of the activity patterns -- if on balance it helps individual contributors, or managers, or executives work more effectively – then its use will propagate, overriding minor preferences that an individual might have based on past experience, working style, aesthetic preference, and so on. An individual preference that is strong enough may of course prevail, but on balance, and over time, conformity within one of these categories is likely. As a gedanken experiment, one can see that the same pressures can operate for individual productivity tools, albeit more slowly. Early word processors were used as improved typewriters, to produce documents that were then printed and distributed. Individual authors could indulge their personal preferences to a great measure, using different software, different fonts, different styles, and discovering different features. When networked PCs and workstations and email attachments made document sharing possible, pressures to conform grew. First at the application level – co-authoring and document sharing became much easier if people conformed on the use of a tool. Once this happened, one reader would see styles, fonts, and other features used by another person. One might borrow a template for a document, slide presentation, or spreadsheet. Best practices can be shared in ways that were less likely with standalone systems. This ongoing process, in which the use of an application by one of the three parts of the organization becomes more uniform, is potentially a major boon to designers of widelyused applications. It will also help those who set about determining system requirements for an organization. Those who deploy and support the system in use will be better able to anticipate issues that will arise. In effect, they will know that for software used by more than one of the three groups, they are working on more than one application. Of course, they still have to get those two or three applications right. But the job of ‘listening to the users’ or obtaining feedback from observation will be a lot easier when you know in advance that they will be speaking in two or three voices. For software used within one group, the job is easier, and pressures that encourage conformity also make the support tasks easier. Insight is still to be derived from considering the activity patterns, priorities, and constraints on that group, and from listening to them. But they may speak with greater harmony. CONCLUSION Some complex applications, project management for example, clearly need different interfaces for managers and individual contributors. But for most applications we do not consider job categories as significant. Calendars are for recording meetings and appointments, whoever you are. Pretty simple. But not true—different sets of demands and constraints lead people with certain roles to use even basic tools very differently. The striking aspect of this phenomenon is that however obvious it might seem in retrospect, people have not paid attention to it at all. The case studies described here are drawn from three major international organizations, all with outstanding people in the fields of requirements analysis, design, product deployment, and customer support. Repeatedly, the most significant problems that they and their customers faced in addressing this category of software could be traced to this single oversight. REFERENCES 1. Fischer, G., Lemke, A. & Schwab, T. (1984). Active help systems. In T. Green et al. (Eds.), Proc. European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics, 116-131. Springer-Verlag. 2. Grudin, J. and Palen, L. (1995). Why groupware succeeds: Discretion or mandate? Proc. ECSCW'95, 263-278. Kluwer. 3. Henderson, D.A. Jr. (1986). The Trillium user interface design environment. Proc. CHI’86, 221-227. 4. Horvitz, E. (1999). Principles of mixed-initiative user interfaces. Proc. CHI’99, 159-166. These findings lead to two concrete recommendations. First, if an application is intended to be used significantly by more than one of the three to five categories identified by Mintzberg, then the requirements, design, deployment, and support efforts should consciously focus on the relevant categories. Observations, interviews, surveys, user tests – all should analyze these categories independently, not merging the data. 5. Mackay, W. (1990). Users and customizable software: A co-adaptive phenomenon. Ph.D. Thesis, Sloan School of Management, MIT. This is not necessarily more work. Within each category, there is likely to be much less variance, so fewer people will be needed. The same number of participants should yield much cleaner data, in fact, because a significant source of variability is accounted for. 7. Mintzberg, H. (1984). A typology of organizational structure. In D. Miller and P. H. Friesen (Eds.), Organizations: A quantum view (pp. 68-86). PrenticeHall. Reprinted in R. Baecker (Ed.), Readings in groupware and computer-supported cooperative work. Morgan Kaufmann, 1993. Second, professionals engaged in requirements analysis, design, deployment, support, training, and so forth can work to build up their intuitions about the organizational behaviors they face. Read the literature, examine the use of software already deployed, identify the organizational types and roles in the settings of interest. Where I have looked, the lack of awareness has been significant, so it should be relatively easy to make fast progress. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Steven Poltrock and Leysia Palen are major contributors to this work, providing access to field sites and discussing the observations. Marshall McClintock, Eleanor Wynn, and Gayna Williams provided useful comments. This research was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant #IRI-9612355. 6. Markus, M. L. (1983). Power, politics, and MIS implementation. Communications of the ACM, 26, 6, 430-444. Reprinted in R.M. Baecker and W.A.S. Buxton (Eds.) Readings in Human Computer Interaction. Morgan Kaufmann, 1987. 8. Orlikowski, W. (1992). Learning from Notes: Organizational issues in groupware implementation. Proc. CSCW’92, 362-369. ACM. 9. Palen, L. (1998). Calendars on the New Frontier: Challenges of Groupware Technology. Dissertation, Information & Computer Science, University of California, Irvine. 10. Perin, C. (1989). Electronic social fields in bureaucracies. Proc. American Anthropological Assoc. Conference Session on Egalitarian Ideologies and Class Contradictions in American Society.