Economic Globalization and Scottish Nationhood since 1870

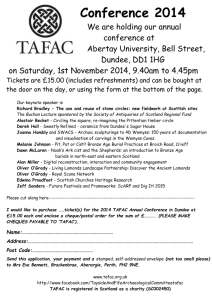

advertisement

The Economic basis of Scottish Nationhood since 1870* Paper for the Economic History Conference University of Warwick, 28-30 March 2014. Jim Tomlinson, University of Glasgow Scotland faces an independence referendum in September 2014 on the back of a resurgence of Scottish nationalism which led to the election of a majority SNP government in Edinburgh in 2011. This nationalist upsurge raises the question of how far we can talk about a Scottish ‘national economy’, and whether there is in this regard a ‘material base’ for Scottish nationalism. This issue is addressed historically through looking at the development of the Scottish economy, especially in the period since 1870. Economic nationhood is ‘imagined’ in historically contingent ways. 1 For much of the twentieth century it was commonly imagined through the construction of National Income Accounts, the circular flow of income and GNP. 2 But such constructions usually relied on the nation having statehood, so that the state apparatus treated the national economy as coterminous with the state’s own boundaries. Unsurprisingly, therefore, Scotland, has until recently not had this statistical underpinning of economic nationhood. 3 While the first National Income accounts for Scotland were constructed in the 1950s, no official data was published until the 1970s, and only today are their efforts underway to construct comprehensive historical Accounts. 4 A similar absence relates to other macroeconomic data; there are no systematic historical balance of payments data, nor estimations of a Scottish inflation rate. 5 However, Scottish data on unemployment rates exist from the 1930s, with Scotland a ‘region’ of the UK for specification of the ‘regional problem’. 6 I am grateful to Jim Phillips and Duncan Ross for conversations on the topic of this essay. 1 A. Benedict, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (2nd. ed. 1991). 2 A. Tooze, ‘Imagining national economies: national and international economic statistics, 1900-1950’ in G. Cubitt (ed), Imagining the Nation (Manchester, 1998) pp.213-4; idem., Statistics and the German state, 1900-1945: the Making of Modern Economic Knowledge (Cambridge, 2001); A. Cairncross, ‘The development of economic statistics as an influence on theory and policy’ in D. Ironmonger, J. Perkins and T. Hoa (eds.), National Income and Economic Progress (Basingstoke, 1988). 3 For the case of Wales, see T. Boyns, ‘The Welsh Economy-historical myth or modern reality?’ Llafur, Journal of the Welsh People’s History Society 9 (2005), pp.84-94. 4 T. Johnston, N. Buxton, D.Mair, Structure and Growth of the Scottish Economy (London, 1971), chapter 6; A.D. Campbell, ‘Income’ in Cairncross (ed.), The Scottish Economy (Cambridge, 1954), pp.46-64; some of these statistical issues are discussed in B. Jameson (ed.). An Illustrated Guide to the Scottish Economy (London, 1999), especially pp.169-178. 5 On the Scottish balance of payments, see W. Murray ‘Trade’ in Cairncross, Scottish Economy, pp.133-148; S. Dow, ‘The Scottish balance of payments’ Royal Bank of Scotland Review, (160) 1988, pp.12-22; N.Hood, ‘Scotland in the World’ in Jameson, An Illustrated Guide, pp.38-53. 6 In general, there is much more data on employment and the labour market in Scotland reflecting a) the persistence of high unemployment rates, b) a common belief in the literature that Scotland’s particular economic history has largely reflected changes in its sectoral output and employment patterns. A key way Scotland has been imagined historically is as an ‘industrial nation’: W. Knox, Industrial Nation: Work, Culture and Society in Scotland 1900 to the Present (Edinburgh, 1999); C. Macdonald, Whaur Extremes Meet: Scotland’s Twentieth Century (Edinburgh, 2009), especially pp.3466. For the particular specification of the ‘problem’ of the Scottish Highlands, see A. Perchard and N. Mackenzie ‘”Too Much on the Highlands?” Recasting the Economic History of the Highlands and Islands’ Northern Scotland 4 (2013), pp.3-22. 1 Another starting point for imagining Scottish economic nationhood historically is the debate about globalization and nationhood. In the final chapter of his Nations and Nationalism, Eric Hobsbawm observes that: ‘”The nation” today is visibly in the process of losing an important part of its old functions, namely that of constituting a territorially bounded “ national economy”…’. But a little later on he concedes that ‘this does not mean that the economic functions of states have been diminished or are likely to fade away’, above all because ‘their growing role as agents of substantial redistributions of the social income by means of fiscal and welfare mechanisms, have probably made the national state a more central factor in the lives of the world’s inhabitants than before’. 7 The first of these claims is a commonplace, though a disputable one.8 The second is more interesting and important. It suggests that the idea of a national economy, in the sense of the nation as an economic ‘community of fate’, is far from out-dated even in an era of globalization. This paper addresses this second claim from the perspective of the history of Scotland. The central argument of this paper is that recent developments in the economy have made Scotland more of a ‘national economy’, an ‘economic community of fate’, than at any time in its history. I Since 1707 Scotland has been part of a Union within Great Britain. At the time of this Union Scotland could be characterised as having a set of largely independent regional economies, some of which had strong connections with Western Europe, some with England and Ireland. Some Scots had also built up small connections with extraEuropean markets and sources of supply in the (English) Empire. 9 It was the desire to expand these imperial connections, and to also sustain trade with England, which seems to have motivated many of those who favoured Union. 10 The new Union was not a highly-integrated and self-sufficient economy. While Anglo-Scottish trade (and probably capital flows?) grew, so did economic links with the Empire. In the eighteenth century the most spectacular feature of Scottish economic development was the growth of the Glasgow tobacco trade, drawing of course on the benefit of servile labour in the British Empire in the Atlantic and Caribbean. 11 But, as Whatley suggests, external connections were especially important in the overall picture of early Scottish industrialization, with both the key textiles, linen and cotton, heavily dependent on imported raw materials and foreign markets.12 But the core of Scottish 7 E. Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism (2nd ed. Cambridge, 1992), pp.181,182-3. On Hobswawm and nationalism, see T. Nairn, The break-up of Britain,(3rd ed Edinburgh, 2003), p. xxviii. 8 For a sceptical discussion of such claims, P. Hirst, G. Thompson and S.Bromley, Globalization in Question (3rd ed, Cambridge, 2009). 9 C. Smout, Scottish Trade on the Eve of the Union, 1660-1707 (Edinburgh, 1963). 10 C. Whatley Scots and the Union (Edinburgh, 2006). 11 T. Devine, The Tobacco Lords (Edinburgh, 1975); however the impact of this in the domestic economy was slight. 12 C. Whatley, The Industrial Revolution in Scotland (Cambridge, 1997), pp.39-44; T. Devine, ‘Colonial Commerce and the Scottish Economy, c.1730-1815’ in L. Cullen and C. Smout (eds.), 2 industrialization in the nineteenth century was increasingly metal manufactures, especially ships and capital goods, with associated developments in coal and iron and steel. This ‘second industrial revolution’ was linked to an even greater globalization of the Scottish economy in the period after circa 1870. II Economic historians have made clear that the first great age of economic globalization came in the second half of the nineteenth century, with Britain at the centre of an unprecedented expansion of international economic linkages encompassing trade, investment and migration. 13 This period of rapid globalization had an important imperial dimension, but at its core was the ‘British world’ connecting the ‘colonies of settlement’ (Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa), the United States, and the ‘informal empire’, especially in countries such as Argentina. 14 In the years up to 1914 Britain became the most globalized economy in the world, with a degree of exposure to international economic forces unprecedented for a major country. Politically this degree of exposure was sustainable not only because, as a limited democracy, major benefits accrued to the ruling groups, but also because the mass of the population, while suffering from major economic fluctuations, benefitted from the cheap food which accompanied this globalization. Only on a very limited scale before the Great War did political pressure emerge to ‘manage’ the British economy, and given the degree of international economic integration, the capacity to exercise such management would in any event have been extremely limited. The gold standard, free trade, and a low and balanced budget, ‘the three arks of the covenant’ of Victorian and Edwardian political economy left very little scope for national economic management. 15 Within this Union Scotland was even more economically globalized than Britain as a whole. At the core of the economic development of Victorian Scotland were the heavy engineering industries of the West of the country, especially shipbuilding, marine engineering and locomotives. 16 All of these industries were heavily dependent upon international markets either directly, or, as in the case of ships, indirectly, via the volume of international trade. 17 Large quantities of coal were also exported; some of this went coast wise to London, but more went to markets in Northern Europe, and overall, including bunkers, 38 per cent of Scottish coal output was exported in 1913. 18 While overall the Scottish economy was moving away from its reliance on textiles, especially because of the lack of ability to deal with competition from Lancashire in cotton goods, the two remaining important textile industries, cotton thread in Glasgow Comparative Aspects of Scottish and Irish Economic and Social History 1600-1900 (Edinburgh, 1977), pp.177-190. 13 M. Daunton, ‘Britain and globalisation since 1850: I. Creating a global order, 1850-1914’ Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 16 (2006), pp.1-38. C. Harley, ‘Trade, 1870-1939: from globalisation to fragmentation’ in R. Floud and P. Johnson (eds), The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain vol II Economic Maturity, 1860-1939 (Cambridge, 2004), pp.164-167. 14 G. Magee and A. Thompson, Empire and Globalization. Networks of People, Goods and Capital in the British World, c.1850-1914 (Cambridge, 2010). 15 R. Middleton, Government versus the Market (Cheltenham, 1996), pp.216-219; J. Tomlinson, Problems of British Economic Policy 1870-1945 (1981), chapter 1. 16 A. Slaven, The Development of the West of Scotland 1750-1960 (London, 1975). 17 L. Johnman and H. Murphy, British Shipbuilding and the State since 1918 (Exeter, 2002), p.7. 18 Slaven, Development, p.166. 3 (J. and P. Coats) and jute in Dundee, were especially globalized, with overwhelming dependence on international sources of raw materials and world markets. 19 In addition, Scotland contributed disproportionately to the extraordinarily high level of British exports of both capital and people. 20 This scale of exposure to international economic forces brought with it especially high levels of economic instability and insecurity, but as in the UK as a whole, the economic costs of globalization were significantly offset by cheap food, at least in the last quarter of the nineteenth century (and again in the 1930s). However, this economic instability was a key underpinning for the emergence of Labour as a political force, though before the Great War organised labour, both trade unions and socialist parties, remained committed to free trade and did little to question the ‘three arks’, so that socialism was not yet centrally associated with demands for a managed (national) economy. 21 Alongside this international orientation, the Scottish economy retained considerable separation from England. Its banks and other financial institutions were largely autonomous, and most of its major industrial corporations were owned and controlled within Scotland. 22 In this sense, we can agree with Payne that: ‘In 1913 Scotland could be said to possess a distinctive semi-autonomous economy’.23 There was, of course, considerable trade across the Anglo-Scottish frontier, with, for example, London playing a major role as an entrepot in the trading of many commodities. But in most respects the Union in this period was a ‘loosely-coupled’ economic entity, with substantially differentiated regional industrial economies, most of which had their strongest ties to imperial and global sources of raw materials and product markets (and local labour markets). Though we do not have precise data, it is likely that, as Cairncross suggested. ‘At the beginning of the present century (ie 1900) America may well have provided a larger market for Scottish products than England and Wales’. 24 Overall, we can argue that by 1913 Scotland probably had the most globalized economy in the world. 25 So it is hard to talk of a ‘Scottish economy’ in this period beyond the sense of an agglomeration of activities within a particular geographical space. There was little of an economic ‘community of fate’. The economic livelihoods of Dundonians rested largely on the monsoon in Asia, the intensity of Calcutta competition in jute, and the state of the American market; that of Glaswegians rested on global levels of trade feeding through to demand for ships, and fluctuations in the 19 On Coats see P. Payne, Growth and Contraction: Scottish Industry c.1860-1990 (Edinburgh, 1992), pp.10-11. On Dundee, Tomlinson, ‘Dundee and the World: De-globalisation, De-industrialisation, and Democratisation’ in Tomlinson and Whatley (eds), Jute No More (Dundee, 2011), pp.1-26 and J. Tomlinson, Dundee and the Empire: Juteopolis circa 1850-1939 (Edinburgh, forthcoming 2014). 20 C. Schmit, ‘The nature and dimensions of Scottish foreign investment, 1860-1914’ Business History 39 (1997), pp. 42-68; on emigration, T. Devine, To the Ends of the Earth. Scotland’s Global Diaspora (London, 2012). 21 F.Trentmann, Free Trade Nation (Oxford, 2010). 22 J. Scott and M.Hughes, The Anatomy of Scottish Capital (London, 1980). 23 Payne, Growth and Contraction, p.48. 24 Cairncross, ‘Introduction’ to Cairncross, The Scottish Economy, p.5. 25 This globalization embraced large scale emigration and capital flows as well as trade; on emigration, T. Devine, To the ends of the earth. Scotland’s global diaspora, 1750-2010 (London, 2011); on capital flows, C. Schmitz, ‘The nature and dimensions of Scottish foreign investment, 1860-1914’ Business History 39 (1997), pp.42-68. 4 world market for capital goods. For the great bulk of Scots, economic welfare was provided overwhelmingly by their (or their household’s) position in the labour market, supplemented by voluntary collective provision (eg friendly societies), philanthropic support, and, in extremis, some support from local public sources in the form of the Poor Law. Only at the very end of the pre-war period were any resources made available from central (ie London) government, for example, pensions from 1908, but though the principle was important, the immediate impact was tiny. Public employment was likewise almost exiguous. 26 III The inter-war period is generally regarded as a period of international economic disintegration or ‘deglobalization’. The disruption of the First War was followed in the 1930s by the break-up of the gold standard, a sharp shift towards protectionism, and a repatriation of both capital and people exports. For such a highly globalized economy as Scotland the results of this disintegration were especially severe 27 Its staple trades were especially hard hit by the two global downturns of 1920-22 and 1929-32, with only limited recovery across the whole period down to rearmament in the late 1930s. Mass unemployment followed, with the largest numbers in the Central Belt, but even higher proportions in such places as Dundee. Scotland’s problems reflected what came to be called an ‘over-commitment’ to a limited range of industries which all suffered from international instability and a variable combination of two trends: a global slowing of demand and enhanced international competition. However, the problems of these industries did not lead to a major switch to ‘new’ industries as occurred in Southern England. While diversification was recognised as desirable, it was forthcoming only on a limited scale, a fact usually accounted for by the low incomes of Scots failing to provide the domestic market for the consumer products which were an important part of these ‘new’ industries. 28 The predominant political response in Scotland to the inter-war economic crisis was to push for Union-wide solutions. While the Labour (and Communist) presence in Scotland grew at the expense of the Liberals, it was the even more Unionist Conservatives who dominated in the 1930s (and who continued to be strong in Scotland until the 1960s). The triumph of Labour in 1945 reinforced Unionist politics; the ‘nation’ which now owned the nationalised industries and the National Health Service, and provided welfare ‘from the cradle to the grave’ was the British nation. Symbolically, the Labour party gave up its formal commitment to Scottish home rule in 1954. The Second War, with its demands for all manner of metal goods, reinforced the ‘over-commitment’ to the Victorian staples, so that by the early 1950s Scotland retained its reliance on heavy engineering and the industries supplying this sector, 26 It is notable that at this time both Liberal and Labour parties were formally committed to Scottish Home Rule. But this seems to have more to do with ideological positioning vis-à-vis Irish Home Rule than any serious sense of Scotland as a nation seeking a degree of political sovereignty. 27 For the first time since the early nineteenth century, Scotland recorded net immigration in the early 1930s, albeit on a small scale. 28 G. Peden, ‘The Managed Economy: Scotland, 1919-2000’ in T. Devine, C. Lee and G. Peden, (eds) The Transformation of Scotland. The Economy since 1700 (Edinburgh, 2005), pp.233-243. 5 coal and iron and steel, with only limited change since these industries’ heyday before 1914. 29 But from the 1950s a process of de-industrialization began in Scotland.30 Its proximate causes, as elsewhere, were shifts in consumption patterns as higher income consumers spent increments of income on services; lower productivity growth in services, so that even with equivalent growth of demand, employment would rise faster than in manufacturing; and the growth of imports of manufacture from foreign countries. 31 Initially this decline in employment did not come from manufacturing, which continued to expand into the 1960s, with a peak in 1965/6. 32 Rather, the contraction began in coal and the railways. In coal the numbers peaked in 1958, and the subsequent contraction was especially striking, with numbers falling by more than half in the following ten years.33 On the railways numbers also fell sharply, especially after the Beeching report of 1963 brought about a major ‘rationalisation’ of the network. Iron and steel employment was sustained longer, into the 1960s, as attempts were made to switch its output from the heavy inputs for ship construction to lighter sheet steel for products like cars. 34 Ironically, these contractions took place in nationalised industries (coal and railways were nationalised in the 1940s; iron and steel renationalised in 1967); public ownership provided a ‘humane’ framework for labour-shedding. 35 This rundown was, until the 1970s, facilitated by an overall buoyant demand for labour, albeit Scottish unemployment levels persistently exceeded those in England. 36 Table I Employment in Scotland 1961 to 1978 (000s) 1961 Total 717 manufacturing Of which: shipbuilding Of which: electrical and instrument engineering 1963 687 1968 701 1971 669 1978 604 49 46 45 41 51 63 69 64 Cairncross, ‘Introduction’, pp.3-4; Peden’ Managed Economy’, pp.243-247. De-industrialization can be analysed from a number of perspectives, but here the focus is on employment, where the term means both the absolute and proportionate fall in the numbers employed in ‘industry’ conventionally including manufacturing, mining, and construction; G. Peden ‘A New Scotland? The Economy’ in T. Devine and J. Wormald (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford, 2012), pp.653-656. 31 R. Rowthorn and J. Wells, De-industrialisation and Foreign Trade (Cambridge, 1987). 32 C. Lythe and M. Majumdar, The Renaissance of the Scottish Economy (London, 1982), Table 3.1. 33 P. Payne, ‘The Decline of the Scottish Heavy Industries’ in R. Saville (ed), The Economic Development of Modern Scotland 1950-1980 (Edinburgh, 1985), p.80; J. Phillips, ‘Deindustrialization’. 34 Payne, ‘The Decline’, pp. 93-98, and on the attempt to create a Scottish car industry, Phillips, Industrial Politics, pp.13-51. 35 J. Tomlinson, ‘A “Failed Experiment”? Public Ownership and the Narratives of Post-War Britain’ Labour History Review 73 (2008), pp.199-214. 36 Peden,‘The Managed Economy’, p.248. 29 30 6 Of which: Metal manufacture Of which: mechanical engineering Of which: Food, Drink and Tobacco Of which: textiles Mining and quarrying Construction Gas, electricity and water Industry Total employment 50 47 46 37 111 108 96 87 91 94 97 91 88 86 72 55 69 45 39 39 173 31 171 31 26 172 28 1,013 2,088 919 2,055 892 2,087 851 2,070 85 Source: Lythe and Majumdar, Renaissance, Tables 3.1 and 4. 10. Heavy engineering also declined from the 1950s, with shipbuilding output peaking in the middle of that decade.37 Jute also contracted after an initial period of post-war stability, aided by the wartime Jute Control which until the 1960s provided tapering protection for the Dundee producers against Calcutta competition. 38 For two decades after the mid-1950s the contractions in coal, iron and steel and railways and heavy engineering were partly offset by an influx of light engineering and electronics activity, much of it based on inward investment by US corporations anxious for ease of entry to Western European markets, and encouraged by subsidies from post-war regional policy. This latter sustained industrial employment, generating 70-80,000 jobs in the 1960s.39 But from the 1970s all trends in industry tended in the same direction. Total manufacturing employment in the UK and Scotland started to decline in the 1960s. The newer sectors of manufacturing which had expanded in the 1950s and 1960s started to contract in the following decade, especially as a result of the retreat of the multinationals. 40 Contraction was also evident in Food, Drink and Tobacco. The long-standing decline in coal, railways and iron and steel continued, albeit at a slower pace until the 1980s. 37 Johnman and Murphy, British Shipbuilding, pp.100-103. J. Tomlinson, C. Morelli and V. Wright, The Decline of Jute. Managing Industrial Change (2011). 39 B. Moore and J. Rhodes, ‘Regional Policy and the Scottish Economy’ Scottish Journal of Political Ecomomy 21 (1974), pp.215-235. 40 N. Hood and S.Young, Multinationals in Retreat. The Scottish Experience (Edinburgh, 1982) 38 7 But in the early 1980s disaster came in the form of the adventurist policies of the Thatcher government, which in an unanticipated fashion drove up the exchange rate at a speed and on a scale unprecedented in the modern history of industrial countries, with an appreciation of, according to different calculations, between 30 and 50 per cent in the space of two years. 41 This appreciation squeezed the tradeable section of the economy, especially manufacturing, leading to a fall in output and rise in unemployment. Though a UK wide phenomenon, this had a disproportionate impact on Scotland. De-industrialization has continued albeit at a varying pace since then, (Table 2). Table 2. Industrial Employment in Scotland 1965-2007 (excluding construction) Year 1965 1979 1993 2007 Percentage of total in employment 39.3 32.3 17.7 11.1 Source: Peden ‘A New Scotland?’ pp.652-3 (based on www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Labour-Market/DatasetsEmployment) IV De-industrialization is widely recognised as key feature of recent Scottish economic history, but poses major problems of interpretation. As Jim Phillips argues, lots of accounts of this process are ‘catastrophist’, in character, greatly foreshortening the period of its occurrence, and especially linking it almost entirely to the Thatcher slump. 42 As Table 1 shows, it began much earlier, and has continued much longer, however much the early 1980s does mark a dramatic intensification and concentration of the downward movement in industrial employment. Second, we can note the predominance of ‘declinist’ accounts, which treat deindustialization as evidence of a pathology of the Scottish economy. For example, Campbell does this for the inter-war period, and Payne for the whole period from 1913 onwards. 43 Scottish declinism has also, like that for Britain coupled its diagnosis with identifying arrange of ‘usual suspects’—such as weak entrepreneurialism, over-mighty trade unions, excessive state spending and taxation and under-investment. 44 Such interpretations may be challenged by noting that, first, Scottish incomes, on trend, have continued to increase in the wake of deJ. Tomlinson, ‘Mrs Thatcher’s Economic Adventurism, 1979-1981, and its Political Consequences’, British Politics 2 (2007), pp. 3-19. 42 Phillips, ‘Deindustrialization and the moral economy of the Scottish coalfields, 1947-1991’, International Labor and Working Class History 84 (201) pp.99.-115; for example C. Harvie, No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Twentieth Century Scotland 3rd ed (Edinburgh, 1998) p.164 characterises the experience post-1979 as ‘instant post-industrialisation’; cited in Peden ‘A New Scotland?’, p.652. 43 R. Campbell, The Rise and Fall of Scottish Industry, 1707-1939 (Edinburgh, 1980); Payne, Growth and Contraction. 44 J. Tomlinson,‘Thrice Denied: ‘Declinism’ as a Recurrent Theme in British History in the Long Twentieth Century’ Twentieth Century British History 20, (2009), pp.227-251. 41 8 industrialization (and relative to the UK average).45 Second, in comparison with the trends in the OECD, Scottish de-industrialization looks fairly unremarkable. In the 1970s the UK and Scotland were close to top of the range of these countries in the share of manufacturing in the total economy, by the end of the century they were about average. This means the fall has been faster than many OECD countries, but it is the starting not the finishing point which is most remarkable. De-industrialization is important in the current context because its disproportionate impact in Scotland, and because of the belief that it is evidence of pathological failings in the economy. Given the role of the state in regulating economic life in the wake of the UK post-war settlement, discontent with economic conditions was readily translated into political discontent. As Jim Phillips has persuasively argued, the beginnings of serious pressure for devolution in Scotland can be found simultaneously with the beginnings of deindustrialization from the 1960s, and the perceived failure of London government to reverse it or address its consequences. 46 Phillips’ focus is on the 1960s and 1970s, but since then de-industrialization has continued apace (Table 2). V For all the rhetoric about Britain living in a ‘neo-liberal’ society, one of the most striking features of the last thirty years has been the growing role of the state in sustaining employment. Up until the 1970s full employment was sustained by macroeconomic policies combined with explicit subsidies to regions. Since then the shift has been, with qualifications, 47 to give priority to holding down inflation as the key macroeconomic goal, and simultaneously regional policy has been much reduced in scale and scope. But over the same period the state has begun to subsidise wages by tax credits on a large scale, and continued the long-run trend towards providing increasing volumes of employment directly in the public sector. 48 Official Scottish Executive figures give public sector employment in Scotland as 580, 000 in 2012, having fallen slightly from its peak of 600,000 in 2009. The 2012 figure represents 23.5 per cent of the total employed population. But there is good reason to suppose that these figures are a considerable underestimate given the amount of outsourcing and the growth of publicly-funded but ‘non-state’ employment. Buchanan et al suggest that adjusting for these boundary problems would inflate the figure for Scotland (for 2007) by almost a third, from the official figure of 580,000 (including G. Peden, ‘The Legacy of the Past and Future Prospects’ in Devine, Lee and Peden, Transformation, p.266. 46 J. Phillips, The Industrial Politics of Devolution. Scotland in the 1960s and 1970s (Manchester, 2008). 47 Most obviously, the major deployment of Keynesian policies to sustain employment in the wake of the financial crash, led by the British and US governments in 2008/2009: S. Wren-Lewis, ‘Macroeconomic Policy in the Light of the Credit Crunch: The Return of Counter-Cyclical Fiscal Policy’ Oxford Review of Economic Policy 26 (2010), pp.71-86. 48 Many public sector jobs were lost due to privatization of previously nationalized industries in the 1980s and 1990s, but here I am focussing on the ‘non-market’ public sector, ie employment in the provision of public services. 45 9 financial institutions) to 772, 000. 49 As it happens, the official 2012 figure is the same as the official figure for 2007, so adjusting the later figure in the same proportion would suggest again a total of 772,000, 31 per cent of the total in employment. These figures seem broadly compatible with those provided by the Centre for Cities on a city basis, which on a basis somewhere between the government figure and the CRESC estimates, gave (for 2009) the Dundee figure as 37.3 per cent, and that for Glasgow as 31.9 per cent.50 This growth of public sector employment matters in the current context because it is a large part of the process of de-globalization evident in Scotland as an accompaniment to de-industrialization. Most historically sensitive accounts of globalization describe a cyclical pattern, with a major upswing from around the middle of the nineteenth century, a ‘downswing’ of deglobalization and fragmentation inaugurated by the Great War, with a return to enhanced globalization evident from the late 1940s, accelerating later in the twentieth century. Yet the historical political economy literature has also recognised that from the late nineteenth century workers have sought protection against the uncertainties and insecurities of a globalized economy especially by seeking state welfare to offset this market insecurity.51 For much more recent years it has been shown that, contrary to fears of a ‘race to the bottom’ in tax and spending levels, exposure to globalization has been positively correlated with state welfare provision. 52 When this process of seeking security leads to expanding employment outside the private sector it can reasonably be said to lead to deglobalization. This broad idea can be applied to Scotland. Historically, high levels of economic insecurity have not been responded to by protectionist and isolationist politics, but by seeking state support for a degree of income security. 53 For the century after 1870s this pressure represented itself politically in ‘the rise of Labour’, which, in an industrial society, sought solutions through policies largely at UK level. But as deindustrialization from the 1960s undermined existing employment patterns, it also undermined the organized working class which had spear-headed the fight for ‘Unionist’ solutions. In a world where a major revival of industrial employment is wholly implausible, the route to greater economic security has de facto consisted in large part of state subsidies to poorly paid service sector jobs and the growth of public employment. Ironically, this has occurred alongside a persistent and substantail erosion of the income security supplied by social security against unemployment, which might be thought of as the ‘classic’ counterpart to the insecurities brought J. Buchanan, J. Froud, S.Johal, A. Leaver and K. Williams, ‘Undisclosed and Unsustainable: problems of the UK National Business Model’ CRESC Working Paper No 75, University of Manchester 2009. 32,000 were employed in public sector financial institutions. 50 Centre for Cities, ‘Public Sector Cities: Trouble Ahead’ (London, 2009), p.9. These figures include employment in universities as ‘public sector’, an assumption more obviously justified in Scotland than England, the latter now having ‘full-cost’ fees for most degree courses. 51 M. Huberman, ‘Ticket to Trade: Belgian Labour and Globalization before 1914’ Economic History Review 61 (2008), pp.326-359. 52 D. Rodrik, ‘Why do More Open Economies have Bigger Governments?’ Journal of Political Economy 106 (1998), pp.997-1033. 53 Though in Dundee in the 1930s, whilst the Labour party remained officially committed to free trade, local party and union leaders entered into alliance with local Conservative MP to press for protection of the jute industry. 49 10 about by globalization. 54 Of course, the forces making for this development have been complex. The rise in public sector employment has been especially in health and social care and education; labour-intensive services demand for which demand is driven relentlessly upwards by an ageing population, increasing expectations about levels of health, and similar increases in beliefs about the desirability of education. It should be emphasized that the persistence of these trends over time has meant that growth has taken place under governments of all political shades, including, at the UK level, the Thatcher government of 1979-1990. 55 This growth of public sector employment is a key, but not the only, facet of deglobalisation, which is occurring simultaneously with the upswing in globalisation brought about by ever-increasing globalisation of manufacturing. But manufacturing is now a small part of economic activity (around 10-11 per cent of GDP), so we cannot take what is happening there as representative of the economy as a whole. The largest part of the economy is now private sector services, whose level of globalisation is extremely diverse. Some elements, such as (part of) financial services and business services are very highly globalised. But others—retail, hairdressing, entertainment—are highly labour intensive and ‘unglobalised’. In addition, as emphasised here, there is the substantial growth of the public sector. There are ‘global’ elements in this area, most problematically the way the NHS sucks human capital out of poor countries to provide nursing and medical staff. But overall these services inject stability and security of employment into the economy, with a very high degree of insulation from global forces. The scale of these public services is largely determined in Edinburgh: the official Scottish government figures show 485,000 out of 580,000 public sector jobs coming under devolved budgets, with the great bulk in the NHS (156,000) or local government (278,000, mainly school teachers). 56 Of course, most of the funding for these jobs currently comes from the national UK tax pool, via the Barnett formula, and since the banking crisis Scotland has been subject to cuts decided in London. But these cuts cannot be seen as in any straightforward way as a result of ‘global’ fiscal pressures on London; they have been the result of political choices. 57 But in any event the London government has ring-fenced NHS and school spending (with qualifications about ‘efficiency savings’) so there is no major threat to these jobs in the foreseeable future. To summarise the argument. From a globalised industrial economy, reaching its peak in the years before 1914, Scotland has become a significantly post-industrial economy with strong de-globalizing elements. Much more of the forces acting upon the Scottish economy are now internal than ever before; above all, political decisions The ‘generosity’ of unemployment pay reached its peak in the 1960s, when the Labour government sought to reduce resistance to economic restructuring by reducing the costs of unemployment. 55 J. Tomlinson, ‘De-Globalization and its significance: From the Particular to the General’ Contemporary British History 26 (2012), pp.213-230. 56 www.scotland/gov.uk/research/0041/00417000.pdf Labour market Briefing March 2013, accessed 18 April 2013. This reflects the fact that transfer payments (social security), which redistributes a great deal of spending power without directly employing very many people is not devolved to Scotland, while education and health are. 57 V. Cable ‘Keynes Would Be On Our Side’, New Statesman, 17 January 2011, pp.31-33; D. Blanchflower and R. Skidelsky, ‘Vince Cable is Working: the Coalition Isn’t’ New Statesman 24 January 2011, pp.37-38. 54 11 made about public spending in Edinburgh, within some constraints imposed from London, matter a great deal. The state of the world economy, however manifested, matters much less to Scotland today than in 1913, or 1932, or 1981. In this sense there is now more of a ‘national economy’ in Scotland than ever before in its history. 12