New directions in the social studies of market(ization)s

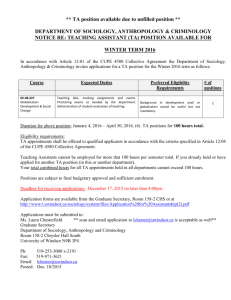

advertisement

1

Economization:

New Directions in the Social Studies of the Market

Michel Callon (CSI-Ecole des Mines de Paris)

Koray Caliskan (Bogazici University, Istanbul)

correspondence email: koray.caliskan@boun.edu.tr

Work in progress. uncorrected English, references to be checked.

Please do not cite or quote without consulting the authors.

Abstract:

The aim of this paper is to outline a theoretical framework for the analysis of markets and

to present the main elements of a program of future research. Locating marketization in

the larger framework of economization, the approach stresses the increasingly dominant

role of materialities and economic knowledge in market making. The paper has two parts.

The first introduces a short history of how researchers from different backgrounds

addressed the question of economization, referring to the actions, devices,

analytical/practical descriptions assembled by social scientists and market actors. In this

process of economization certain types of behaviours, preoccupations, logics of actions,

spheres of activities, forms of calculation or institutional arrangements are defined and

qualified as economic. The importance, meaning and framing of economization are

discussed through an analysis of selected works in anthropology, economics and

sociology. We argue that those works are now leading contemporary researchers of

markets to construct a program of studying economization. The second part of the paper

illustrates this point by focusing on six clusters of research, illuminating the new

directions in the social studies of the marketization as a case study of economization.

Introduction:

Markets are everywhere. Yet studies devoted to their actual functioning are still few. This lack

of research produces a striking contrast between the pervasiveness of the market concept and

the fuzziness of our knowledge on the actual realities to which it relates.

We believe that the lack of interest in the study of concrete markets is the outcome of a long

intellectual and political history.

The aim of this paper is to untangle the social scientific threads in order to give a

disciplinary base back to the contemporary understanding of markets and the dynamics of their

emergence and development. Drawing on the old and new approaches to the market, we

propose a draft research programme to better understand relations of economization of which

markets is a part. The proposed program is an invitation to move on from the study of the

economy to that of economization. We illustrate this point by two moves. First, we review

previous approached developed to study economic phenomena and reinterpret their findings

form the vantage point of contemporary approaches to economization. Second, we review

current research concerning the working of markets and propose a preliminary program for the

social study of marketization. We bridge these two moves with the concept of performativity.

Science studies' recent encounter with disciplines such as economic sociology or

economic anthropology has raised a question that is certainly not new, but that was never

considered as a research priority: the contribution of economics to the constitution of the

economy, i.e., the performativity programme. This encounter has posited that the development

of economic activities, their mode of organization and their dynamics could not be analysed

and interpreted without taking into account the work of economists in the broad sense of the

2

term1. This programme has been captured by Callon in a provocative phrase: no economy

without economics (Callon 1998).

The research concerning the formative relationship between economic sciences and

markets has contributed to the furthering of our understanding of economic phenomena

(Mackenzie, Muniesa, Siu 2007; Callon, Millo, Muniesa 2007; Fourcade 2007; Pinch and

Swedberg 2008). In particular, it has focused attention on a number of new and important

issues. One of them is what Callon called economization (Callon 1998). This term is used to

denote the processes of constitution of the behaviours, organizations, institutions and, more

generally, objects which, in a particular society, are tentatively and often controversially

qualified by scholars and/or lay people as economic. One of the aims of this paper is to

provide elements of analysis to advance the exploration of these processes and to identify a

number of topics to be studies empirically.

The term “economization” implies that the economy is an achievement as much as an

outcome, a starting point or a reality already there that could simply be revealed. The diversity

of scientific or vernacular definitions of the economy or of behaviours and activities qualified

as economic, and the controversies triggered by these definitions, are an indicator of a state of

relative indeterminacy. We talk of economies, of economizing time, for example, or of the

economy of a literary work (to denote its organization). In each of these expressions the

meaning of economy or economic differs. We observe this polysemous diversity in the social

sciences and particularly in economics itself, not to mention sociology, anthropology, business

and political science. The neo-classical definition of economic behaviours is different from

those of institutional or evolutionary economics.

The process of economization is never complete; it is on-going and open. This

incompleteness obviously concerns contemporary societies, whether they have been developed

and economized for a long time, or are still developing and have been economized only

recently. In both cases the sphere of what is considered as the economy is expanding (and

rarely limited) and in turn this expansion alters our conceptions of the economy. This process

also concerns past societies, for which the very concept of an economy or the idea of

qualifying certain behaviours or activities as economic is the result of analytical work by

anthropologists or historians who constantly revise their interpretations. Hence, the

economization of past societies is also an on-going process.

Consider, for instance, Mauss' seminal essay and the long series of anthropological

studies that it inspired. These are still effecting our view of the role of economic activities in

non-Western societies and consequently in Western ones as well. This perpetually unfinished

work, in which present and past societies are redefined, is one of the visible manifestations of

this undertaking of representation and intervention (Hacking, 1999) that can be captured in the

verb 'to economize'.

Asserting that the economy, once it is produced, is variable and polymorphic and that

it cannot be dissociated from the constantly restarted process of economization in which

scholarly and vernacular discourses play an active part, is not a relativist position. Lay and

scholarly knowledge are instituted, maintained, perpetuated, and are able to frame practices

and impose on them the meaning that they attribute to them only if they overcome their own

tests of reality or verisimilitude; one cannot economize just anything, anyhow. Economization

has its own demands and is crowned with success only if it is undertaken properly. The

concept has the advantage of combining the pros of realism and constructivism, without the

torments of relativism. The economy does not exist in a natural state, just waiting to be

discovered, unveiled; nor is it the arbitrary outcome of equally arbitrary discourses. Whether it

is tracked down within our societies or in those which are distant in time and space, the

economy is the result of actions of performation; it is enacted (Law & Mol 2007). This

enactment implies actions which develop simultaneously in a discursive and material sense:

the economy exists as an assemblage, a socio-technical agencement that combines discursive

and material activities. Economizing means establishing agencements which are themselves

Rose and Miller’s work on governmentality have been a decisive contribution to the performativity programme,

even before this programme was formulated. (Miller and Rose 1990).

1

3

interpreted as economic, and which produce this particular version of the economy with

materials that guarantee it a degree of longevity and stability. Hence, economization consists

of a process of establishing socio-technical agencements which are able to do what they say

they do, that is, to make their version of the economy coincide with the way in which they

frame and organize activities that, as a result, match their interpretation of them and can

readily be qualified as economic.

The aim of this paper is to propose a first draft of a research programme devoted to the

study of processes of economization, that is, of the socio-technical agencements they frame

and in which they are embodied. Some aspects of this programme pertain to the various

modalities through which these processes contribute towards shaping what is called the human

being: his/her agency, subjectivity, and mode of socialization. Thus, in certain respects it

coincides with what could be called an anthropology of economization. But agencements have

a collective dimension as well, so that this programme could also be called a social study of

economization. In a sense, it is the will to capture both of these components that could

characterize the way in which we position the programme that we propose.

In the first part we define the concept of economization and situate ourselves in

relation to other similar concepts. The strategy that we have opted for consists in starting from

a set of studies, chosen for their rigour and precision – dare we say their scientificity? –, which

are not explicitly on economization but revolve around the concept and, implicitly,

demonstrate its importance and relevance. This review enables us to position ourselves in

relation to certain established research streams. We analyze two broad strands of research. The

first consists of an analysis of substantivist and formalist debate in economic anthropology.

We show that this debate was instrumental in giving birth to subsequent research on the

economy, teaching us that one cannot qualify an economic situation without mobilizing a

theory of the economy. More technically-speaking, this controversy has shown that the only

way of questioning the economy has been to switch from a noun to an adjective, defining the

observable criteria as economic. The second strand of research we review consists of the

contribution of economics, economic sociology and the anthropology of value regimes.

Drawing on the empirical findings of these three literatures, we present a comparative analysis

of their strengths and weaknesses from the vantage point of understanding various

economization processes.

The second part of the paper presents our definition of economization in general and

marketization in particular. Given the vast terrain of relations that produce various trajectories

of economization, we chose to illustrate the programme we propose by focusing on social

studies of the market, or to better put it, marketization. We have therefore decided to focus on

only one of the modalities of the economization process, the one that leads to the

establishment of economic markets (or, in our terminology, market socio-technical

agencements), that is, the processes that we call marketization2. The reasons for this choice are

multiple. The study of marketization provides a clear illustration of what a study programme

on economization in general could be. Moreover, marketization is at present unquestionably

the dominant, even hegemonic, form of the oldest movement of economization. Nowadays

economizing primarily means marketizing. Finally, there are many studies on markets and

their socio-technical construction. The programme for studying marketization that we propose

and outline here makes it possible to link up as yet disparate studies whose numbers and

diversity are growing. We summarize the finding of the new directions in the social study of

markets under six headings: Things, Agencies, Encounters, Price, Market Maintenance, and

Market-Writ-Large. Arguing that these new research trajectories differ from what is usually

called the study of the social construction of markets, we show that a new programme of

research seems to be emerging in the social studies of marketization.

In the conclusion we examine the tracks opened by these new directions, especially the

question of the role of experiments in the process of marketization, and the role that the social

sciences could have in designing such experiments.

2

Marketization is a sub-set of economization. In this paper we only consider the most recent aspects of the process.

4

I. In search of economization

Until recently, economization as a process that established activities, behaviours, spheres or

fields qualified as economic (whether there was consensus on that qualification or not), was

not considered as a research subject in its own right. The reason for this is obvious. The study

of economization cannot be dissociated from that of the effects produced by those disciplines

which, directly or indirectly, analyse the economy. But the social sciences, like the natural or

life sciences with which they share the same ideal of objectivity, have always been very

reluctant to consider their impacts on the objects that they study, due to the epistemological

difficulties that this type of questioning entails. We felt that one way of lessening these

difficulties, or at least of circumscribing and relativizing them, was to start off from social

science studies which at some point have directly raised the question of the identification or

characterization of the realities that they qualify as economic. By studying them in their

undertaking of creating their own research subject, there is probably a lot to be learned about

the mechanisms through which they contribute towards transforming the realities that they

study.

The aim of this necessarily superficial, limited and selective inventory is to suggest

two things. First, due to their systematic and rigorous nature, these studies show (unwittingly)

the dead-ends to which research leads when it is loath to question its own contribution to the

constitution of its research subject. They also show that a way of putting an end to this

paralysis is to give a name, economization, to these mechanisms rather than turning around

them without naming them. In short, the message delivered, implicitly of course, is that to

study the economy one has to start by studying economization. Second, even though these

studies have not directly addressed the subject of economization, they provide conceptual and

methodological tools to constitute it as a research subject in its own right. The stumbling

blocks that it has encountered (how to agree on what can be qualified as economic?) and the

dynamic that they have followed in their endeavour to overcome them, yield valuable clues as

to what a research programme on the process of economization might be.

We will start this inventory with the famous controversy between formalism and

substantivism, which has been instrumental in shaping subsequent research on the economy.

This debate has been reported on extensively and our aim in revisiting it is to highlight one

aspect which, in our opinion, has not been sufficiently emphasized. The controversy between

formalists and substantivists teaches us that one cannot qualify an economic situation without

at some point mobilizing a theory that defines what is meant by economy. More technicallyspeaking, this controversy has shown, it seems, that the only way of questioning the economy

has been to switch from a noun to an adjective. In other words, rather than asking what the

economy is, one has to define the observable criteria which enable one to say that an activity,

behaviour or institution is economic.

After an analysis of this debate (I.1), which serves also as a reminder of its content for

those readers unfamiliar with it, we show how different disciplines have pursued this

exploration and how they have indirectly, without any explicit questions, highlighted the fact

that the establishment of an economy involves arrangements, institutional and material

assemblages, without which it cannot exist and be sustainable. For reasons pertaining to space

and competencies, we have limited our analysis to three contributions: that of economics, of

economic sociology, and of the anthropology of regimes of valuation (I.2). It would probably

have been possible to review other analytical approaches, but we felt that these three sufficed

to show what needs to be added to economics to account for the process of economization.

At the end of these two sections, we hope that the reader will have a more precise idea

of what we mean by the process of economization and of the terms on which it has to be

studied. At the same time, we would also have shown the contributions and limits (from our

point of view) of some of the most popular approaches.

I.1. Qualifying the Economy: Formalists and Substantivists

5

The debate between formalists (F) and substantivists (S) reached its climax at the end

of the fifties and during the sixties. From the point of view of interest to us here (that of the

process of economization), we need to emphasize that formalists and substantivists shared the

same conviction: to decide on the nature of economic activities and their place in collectives,

the only acceptable approach is first to define a number of theoretical hypotheses and then to

make and collect theoretical observations that serve to confirm or invalidate them. As good

scientists, close to an epistemology that could be qualified as Popperian (quite popular among

researchers in those days), S and F are directly opposed not over the definition of the economy

or of what should be qualified as economic, but over the capacity of their definitions to

account for the variety of the observable real. What They denote by the word economy is not a

real object but a theoretical one whose robustness and relevance have to be tested. In short, F

and S meet to consider that the economy and what it is and does are in the hands of the

theoreticians; hence, it depends on economics. We would say that scientific work is an

essential component of the work of economization of the observed realities, and the modalities

of that economization are as numerous as the theoretical convictions engaged in the debate.

The Popperian epistemologist has the advantage of making this multiplicity of points

of view on the economy compatible with a realistic conception of the economy. This realism

can be strong if the scientist considers that the real matches the theory (when the facts argue in

its favour); it is weak if the scientist refuses to say anything at all on the real, and is content to

assess the relative degree of verisimilitude, fecundity or power of the theories developed

(Callon, 1994). In both cases the theory is subjected to a test of reality, which is that of the

observation of the facts anticipated by the theory. The controversy is not about the theoretical

objects themselves but the observable phenomena postulated in the assertion of the existence

of those objects. This form of realism makes it possible to reconcile the recognition of the role

of the theory with the criticism of relativism as an epistemological position. Thus, economics

is clearly a stakeholder in the object that it constitutes and the soundness of that object can be

tested in the controversy over the observable facts. Another way of summing up this

epistemology, on which the protagonists implicitly agree, is to emphasize that it exits the

aporias of relativism by making a move: to grasp the economy one has to look at that which is

economic since all that is visible are the qualities of the object, its characteristics, and not the

object itself. This shift from a noun to an adjective is the first step on the path to the study of

economization. In this move leading to the study of economic-X (in which X could be a

behaviour, a way of reasoning, forms of activity, institutions, or arrangements) and not of

economies, the role of economics is central. It is economics that is invoked to explain what

these Xs are and why they can be qualified as economic. We are now going to demonstrate this

point by considering, in turn, the positions and arguments of F and S which, beyond their

divergences, afford an identical framework for the study of processes of economization.

The Formalists: economizing individual behaviours

The F's position is closely linked to neoclassical economics which defines the economy by its

object, that is, the study of the maximization of utility under conditions of scarcity. In this

approach, the pivotal notion is instrumental rationality: individuals are decision-makers and

choose between alternative means to maximize their utility (maximization of utility with the

minimum input or effort). This necessity to choose implies a situation in which available

resources are scarce and are used to achieve various goals.

Formalism consists in asserting that all human societies can be analysed as collections

of choice-making individuals whose actions imply trade-offs between alternative ends and

similarly alternative means to attain them. (Salisbury, 1962; Pospisil, 1963; Belshaw, 1965;

Cook, 1968; Epstein, 1968; LeClair, Schneider et al., 1968; Swetnam, 1973; Schneider, 1974).

To guarantee the universality of this model, one simply has to posit that the ends pursued are

culturally defined. The goals assigned to the action do not necessarily refer to monetary or

financial values but to everything that is valued by individuals in terms of religion, ethics,

power or altruism. As we can see, the model of instrumental rationality is sufficiently abstract

(it is enough to distinguish means from ends and to posit that individuals are endowed with

adequate calculative capacities) to have a universal scope and simultaneously to account for

6

the wide diversity of observable realities. From this point of view, the concept of culture is

crucial because it makes it possible to explain why certain ends and means are valued more

than others within a particular community, as individuals can moreover conform to these

values or reject them. When markets with monetary prices exist the model is applied explicitly

in its full force and purity (Fifth, 1961; Laughlin, 1973).

In this approach the economy as a set of activities is a secondary, not a primary notion.

Actually, the Formalists care little about defining the economy since it is everywhere. The

subject of their reflection and investigation is more simple and general: it concerns individual

action and its universality. This subject is obviously theoretical. It is advanced as a hypothesis,

and the supporters of the programme are left to verify whether empirical observations confirm

its validity. The advantage of this approach is its immense conceptual economy(!). A single

concept, instrumental rationality, is mobilized to account for the diversity of existing societies.

It would moreover be more accurate to say that two concepts are needed here, for individual

instrumental rationality is linked to culture, and the latter accounts for the variations whose

boundaries are defined by the former.

Another way of describing this approach is to say that the formalist programme

defines individual human action as an economizing behaviour (with economizing being

synonymous here to instrumental rationality) whose modalities, forms and expressions vary,

depending on the cultural model. We see how the Formalists lithely get rid of the question of

the economy by focusing on economic behaviours which are, more exactly, economizing

behaviours. The noun is replaced by an adjective (in this case a gerund) applying to an X that

(in this case) is individual action. From there, contending that the economy is consubstantial

with human cultures is one easy step that it could be tempting to take.

It stands to reason that these behaviours, qualified by the social scientist as economic

or economizing, do not necessarily correspond to what these qualifiers denote in everyday

language, or to what some associate with the economy in scholarly discourse. In cultures that

have price regulating markets (briefly, of the Western type), the theoretical and common

meanings can be similar. In other cultures, the analyst reveals logics which are ignored (even

denied) by the categories of practice: like any good science, economics (in this case neoclassical) contributes towards making visible the regularities and determinations which,

without it, would remain invisible to the actors themselves who unknowingly follow them. It

may seem that economizing behaviours exist only in certain types of society (developed

Western societies); in fact, and this is at least what the Formalists implicitely claim, they can

be seen everywhere, provided one has the right tools for analysis and observation. The analyst

produces an effect (of surprise) which corresponds to the role that economics plays in the

construction of economic reality, in what we call the process of economization.

The formalist approach can be characterized as an anthropological research

programme in its own right. It postulates the universality of instrumental rationality and the

"economic" behaviours that it induces, and uses the notion of culture to account for the

diversity of the concrete actions observed.3 The Formalists urge us to recognize that: a) from a

scientific point of view – the only one that allows for discourse to be put to the test of reality –,

what needs to be defined is not the economy but the individual behaviours that are qualified as

economic or economizing; both theory and observation focus on the epithet (economic) or the

gerund (economizing) and not the noun (economy); and b) the observable variations cannot be

ascribed to differences in the ways in which individuals are assumed to take their decisions: in

all cases they maximize their utility; they are explained by the modalities of valuation of ends,

which depend on culture. Anthropology, centered on cultural variations, is the continuation of

economics by other disciplinary means. As a result, economization remains caught in the

circle of academic disciplines.

3

Thus characterized, the formalist programme can be greatly enhanced as "progress" is made by economics or

rather by certain strands of economics. The individual agent's calculative capacities can be upgraded to take

strategic interactions into account, as in game theory. It is also possible to introduce information searches and to

select less restrictive optimization criteria by replacing the criterion of maximization by that of satisfaction, or by

introducing the simple ranking of preferences.

7

The Substantivists: Economizing societies

The substantivist approach was first proposed by K. Polanyi in The Great Transformation.

Like the formalist approach it has an implicit epistemology in which the economy or, more

precisely, what is commonly qualified as economic, depends on definitions proposed by

economics. The Formalists draw their inspiration from neo-classical economics; the

Substantivists turn to another, older stream, that of political economy. The former made the

rational individual the cornerstone of their theoretical framework; the latter place the notion of

society and the institution, derived from it, at the centre of their analyses.

For the Substantivists, the existence of behaviours, activities and forms of organization

which, in any society, can be qualified as economic, stems from the fact that, in order to

survive, humans everywhere rely both on nature and on their fellow beings. The term

economic qualifies everything which, in a given society, can be linked (by the observer armed

with her or his theory to verify/invalidate) to the mechanisms and arrangements through which

that society meets its material needs.

The Substantivists' economy is thus an economy of action embodied in a wide variety

of institutional configurations: there are a thousand ways of acting and organizing to survive or

subsist! To describe the institutional variety of these collective subsistence activities, the

Substantivists introduce distinctions which vary with the authors, but are generally inspired by

those proposed by Polanyi. For the author of The Great Transformation, the economy can be

likened to an institutionalized process. This process, which causes goods to circulate from

hand to hand, is organized around a triple distinction borrowed from political economy. In a

semi-empirical, semi-logical sequence, this distinction separates production, distribution and

consumption. If it is to be sustainable the process, which is universal, has to be framed by

institutions, variables, which weave interdependences between individuals and ensure that they

contribute to the different collective subsistence activities. Institutions ensure the viability of

these activities by giving meaning (most often not explicitly economic) to the technical and

materialized operations that individuals carry out to survive. The different resulting

institutional configurations can be described from the point of view of both the forms of

interdependency that they favour and the social structures that they mobilize. K. Polanyi thus

proposes a distinction between three eventualities: reciprocity, which needs groups of long

lasting relations in order to develop; trading, which takes place in markets; and redistribution,

which implies the existence of a centralized structure.

With the analysis of institutionalized processes, the accent is no longer on individual

"calculations", whether conscious or unconscious, but on the way in which goods circulate and

move from hand to hand: activities of production, distribution and consumption are grounded

in logics and collective structures that define forms of engagement and relations between

individual agents. By favoring this approach, the Substantivists are part of a longstanding

tradition in anthropology (marked, in particular, by the prestigious figures of Mauss and

Malinowski). They are also in a position to strengthen their ties with political economy (which

shares the idea that a society's economic activities stem from its most essential requirements

and that they are logically divided between production, distribution and consumption),

primarily with the Marxist tradition and its strong accent on the circulation of goods

(especially commodities).

The examination of the various existing modalities of circulation enables the

Substantivists to underscore the diversity of forms of rationality that prevail on both a

collective and an individual level. Instrumental rationality is simply one eventuality among

others, which corresponds to bartering or trading. The forms of circulation linked to

reciprocity or redistribution obey different logics and rationales. Polanyi's typology is

moreover simply a starting point. Like any classification, it can, and must, be revised on the

basis of observations made. Sahlins (1960, 1972), for example, distinguishes between

generalized reciprocity and restricted reciprocity (he argues that bartering and trade are a

negative reciprocity), thus highlighting the contrast between the gift without a counter-gift

(excluding any form of calculation) and the gift followed by a counter-gift (which implies a

calculation); Gudeman (1986, 2001) distinguishes between communities and markets;

Godelier (1975, 1977) follows the same line of research by linking individual rationality, as

8

described by the Formalists, with the rationality of the capitalist mode of production. In the

analysis of these different modes of circulation, of which there is an abundance of illustrations,

the idea is maintained that each of these modalities corresponds to goods whose nature and

sphere of circulation may differ.

Apart from the diversity of the classifications that they propose, the Substantivists

agree among themselves that the market and the instrumental rationality that it promotes are

simply one eventuality among others. Any society – and this point is emphasized by Polanyi

himself – combines the different regimes in a way that is variable and empirically analysable.

Pure gifts, gifts and counter gifts, bartering and redistribution are present, with trade, in

Western societies which are wrongly described as market societies. Likewise, in non-Western

societies the most extreme forms of calculative behaviour (negative reciprocity) can exist, in

which everyone can acquire the goods they want free-of-cost or at a minimal cost (everyone

can try to maximize their interests at others' expense, through guile or fraud). What the

Substantivists nevertheless agree to recognize, is the existence of a divide between Western

and non-Western societies: self-regulated, price-regulated markets are found only in the

former.

Thus, the S have an approach very similar to that of the F. Like them, they avoid

giving general criteria which would make it possible to identify, for sure, that which in a

society could be considered as "its" economy. Their implicit epistemology, identical to that of

the F, makes them more interested in that which is economic, in what we have called the

economic-X. It is on the identity of the X that they differ. For the F, the X are individual

behaviours, whereas for the S they are the societies themselves; it is societies and not

individuals which, by necessity, are compelled to act "economically". To define and

characterize the activities that in a given society can be characterized as economic, the S, like

the F, resort to economic theory. In contrast they fit into the political economy tradition and,

with it, consider that producing, distributing and consuming are the base on which the variable

institutions shaping the collective and individual logic (or rationality) of these activities

develop. As in the case of the F, the process of economization starts with economics, but

rather than extending into an anthropology of cultural variations, it opens onto a sociology of

institutional differences.

Formalists vs Substantivists

There are obviously several ways of describing and analyzing the debate between Formalists

and Substantivists. We believe that it would be caricaturized and misleading interpretation to

see the debate as nothing but two opposing approaches, one focused on the priority that it says

should be given to individual rational agents, and the other on the pre-eminence of social and

institutional structures. Actually, the two camps share the same bipolar conception of

economic activities. The Formalists start with the individual and arrive at the culture that they

conceive of as a force and a case of coordination and integration; the Substantivists start off,

symmetrically, from the existence of institutionalized processes and mechanisms of integration

and reproduction that they establish, to describe and analyse the different observable

modalities of individual engagement. The disagreement pertains not to the distinction between

individuals and structures, but to the way of defining each of the terms and of describing the

distribution of agency between them.

This agreement on the essential (the agency/structure dichotomy) is one of the reasons

for which the parties in the formalist/substantivist debate described their respective positions

in exactly the same terms, as the following excerpts show.

Scott Cook, one of the outspoken formalists and author of the main article that fuelled

the debate with the strongest contentious power, “The Obsolete ‘Anti-Market’ Mentality: A

Critique of the Substantive Approach to Economic Anthropology,” wrote,

“Economic anthropology … is plagued by a series of communication

gaps between its practitioners. Since the impact on the field of the

writings of Karl Polanyi and his followers, a clear-cut dichotomy has

emerged between scholars who maintain that ‘formal’ economic

9

theory is applicable to the analysis of ‘primitive’ and ‘peasant’

economies and those who believe that it is limited in application to the

market-oriented, price-governed economic systems of industrial

economies.” (Cook 1968)

Cook chose his article’s title in relation to that of an essay Polanyi had written more than two

decades earlier, “Our Obsolete Market Mentality” (Polanyi 1947). For Cancian, a critique of

Cook, the parameters of the debate were almost the same:

“The formalists say that economics is the study of the allocation of scarce

means to alternative ends. That is, it is the study of economizing, or the way in

which people maximize personal satisfactions. Economists have some theories

about how people do this, say the formalists, and there is no reason to think

that these theories are not general enough to be helpful in the study of nonWestern societies. In fact, say the formalists, some scholars have shown that

they’re helpful in understanding events in non-Western societies. No, say the

substantivists, economic theory is based on the study of economies where the

point is maximization of profit by both parties to a transaction, and nonWestern societies are not like that, so the theory is not general enough and

will not apply to non-Western societies… Economic anthropology is about the

institutions surrounding the provision of the material necessities of existence

to man”. (Cancian 1968)

For another critique of formalism, “… the main issue of contention [was] whether the

concepts and propositions of formal economics … [were] also applicable to the analysis of

non-market economies. The formalists say they are applicable and the substantivists that they

are not” (Kaplan 1968).

Marshall Sahlins clearly illustrated this deliberate refusal to ask the question of the

existence of the economy, while (unwittingly?) highlighting its importance. Dragging “the

economy” into the heart of anthropology in the late 1950s, he wrote in his article “Political

Power and the Economy in Primitive Society”:

“To live is to economize, but this indicates the worthlessness of so defining an

economy. The question is whether economic choices are specifically determined by

the relative value of the goods involved. If so, as can be true only in a price-setting

market system, then the entire economy is organized by the process of maximization

of economic value. If not, as in primitive societies where price-fixing markets are

absent and social relations channel the movement of goods, then the economy is

organized by these relations… We are indebted to Karl Polanyi for pointing out the

logical weakness of the identification of economy with economizing” (emphasis added,

Sahlins 1960).

As these excerpts show, the protagonists agree on the fact that, if the controversy is all

about defining that which is economic and that which is not, the only way of drawing the line

between the two is by means of the various available economic theories and by empirically

testing their validity to evaluate both their possibilities for application and their relevance. For

both camps, research is synonymous with producing and recording an increasing number of

empirical findings, field work accounts and "data". The aim is either to show the validity of a

few formalist assumptions in order to account for the diversity of observable individual

behaviours, or to show the validity of the distinctions proposed by the Substantivists in order

to describe the modes of production/consumption of goods and their regimes of circulation.

We could never over-state just how productive this approach has been (see below).

From our point of view, it has the advantage of reminding us, very clearly, that, scientificallyspeaking, it is not possible to study the economy without the theories that talk about them and

whose validity and relevance are evaluated by means of the empirical tests and observations

10

that they imply. In the case of the Formalists, as in that of the Substantivists, this results in a

dual movement. The first triggers interest in that which is qualified as economic: for the

Formalists, this is individual behaviours and, more particularly, the way in which individuals

take their decisions to fulfill their needs; for the Substantivists, it is societies confronted with

the need to survive and live.

This movement corresponds to an essential component of what we propose to call

economization, and it provides a first approach. Economizing means explaining and clarifying

that which can be qualified as economic in behaviours and in collective or individual

activities, or in both at once. Both Formalists and Substantivists clearly show that this

qualification is based on the construction of the more or less formalized, more or less

theoretical discourse that defines its nature. The word qualification is important here: it means

that it would be illusory and unrealistic to talk about what the economy is before agreeing on

what is considered to be economic.

To be sure, and this is the second movement, once the robustness of certain

qualifications has been tried and tested (especially through the trials of reality constituted –

from the point of view of the epistemology shared by Formalists and Substantivists alike – by

factual observations), it can be posited that there really is something which we call economy

and which explains that economic-X are observable (where X is an individual rationality or an

institutionalized process). As shown below, economization can encompass this return

movement, the conditions of which still need to be studied in detail. But Popperian

epistemology is unsuited to such an extension, for it overlooks the socio-technical

agencements necessary for the process of objectification. Whether we limit ourselves to the

first movement or include the second, economization is embedded in economic theory and,

like it, is multiple: Formalists opt for neo-classical theory, while Substantivists prefer the

political economy tradition.

I.2. Institutions and materialities: Economics, Embeddedness Approach of Economic

Sociology and the Anthropology of Regimes of Value

The study of economization cannot be dissociated from the mobilization of economic or socioeconomic theories designed to identify the realities that they qualify as economic and that are

supposed to be observable. That is the main lesson that we learn from the debate between F

and S. But what the controversy also shows is that it is no longer possible to talk of

economization in the same terms. If this programme is to be completed, certain difficulties

need to be overcome. Economization starts with economic theory but the qualification

enterprise stumbles against a series of obstacles that the debates between F and S have

highlighted. Saying that economizing means identifying economic-X is a considerable step

forward. But the controversy has not clarified the identity of the X. It has nevertheless

suggested that, at least initially, one has to disregard individuals and society, and focus on the

intermediate X, especially the institutional processes and the mechanisms of valuation.

The formalist approach needed the notion of culture to end its demonstration; it relied

on culture to explain the observable differences between societies. On this point, it seems

accurate to say that the formalist enterprise ended suddenly, not due to the Formalists

themselves but simply because anthropology veered away from the notion of culture which

proved to be empirically ungraspable. Concepts such as “symbolic order” or “the imaginary”

have gradually been preferred. The Substantivists, on the other hand, have developed the

concept of embeddedness which leads to the description and differentiation of institutional

configurations, modes of circulation of goods or forms of organization of productive or

consumptive activities: the concept of institution, with the interdependencies and modalities of

coordination that it implies, allows for the empirical and theoretical examination of these

differences. Of course the analysis of institutions remains, to better understand how they

contribute towards making certain activities economic.

In addition the controversy has made it possible to explicitly address the question of

the divide between Western and non-Western societies, in an argued way. On this subject, the

11

F's and the S's positions are both similar and different: similar in so far as they tend to consider

that Western societies are distinguished from others by the existence of price fixing markets

not found in non-Western societies4; different because the Substantivists accept the Formalists'

position on the West and question the applicability of formalist hypotheses in the non-West. In

doing so they merely replicate the more general assumption that anthropology is the study of

the non-West, and leave the Formalists with the advantage of a symmetrical position: the nonWestern individual is not ontologically different from the Western one; the only thing

distinguishing them lies outside of them, in the content of the cultures in which they live. This

was the Substantivists' weakest point, for they handed an easy victory to the Formalists on a

topic with which the latter were not prepared to deal ethnographically. However, one of the

Substantivists' essential contributions was to resist the Formalists' assumption that

economizing is a one-sided process, by showing the variety of forms taken by the economic

activities presented. The Substantivists see non-market forms of economy not only in nonWestern societies but also in Western ones. What the controversy finally leaves us with is a

series of questions on the existence of different forms of economic rationality, spheres or

regimes, and on their radical separation or, on the contrary, their constituent entanglements.

This affords a direction for the analysis of institutionalized processes and consequently

institutions.

One of the key questions raised by the Formalists and the Substantivists pertains

indeed to the valuation of goods that are produced, circulated or traded. As we have seen, for

the F, the singular and historically contingent culture in which individuals are immersed

explains why certain preferences prevail and certain choices are made. For the Substantivists,

valuation stems from the institutional mechanisms which format and organize the regimes of

circulation: value is not assessed in the same way in trade, in redistribution and in a

relationship of reciprocity, and the goods that are oriented towards one type of regime or

another do not have the same characteristics. Monetary valuation in terms of prices is simple

one case among many others.

How does an institutional configuration contribute towards the emergence of

economic activities and behaviours? What do we call economic valuation? To understand the

dynamics of the process of economization, as we define it, it is necessary to answer these

questions, for a precise delimitation of the economy, or rather of economic-X, will depend on

them. This is the perspective in which we are now going to examine three disciplines that are

going to help us to further our understanding of processes of economization.

I. 2.1 Economics: Institutions as Socio-Cognitive Prostheses

The real followers of the now obsolete formalist anthropology are its midwives: economists.

They enhanced and amended its core assumptions and even incorporated some central ideas of

the anti-formalist stance.

In many different schools of economic research, concepts of institution and culture

have increasingly become central even in simplified and disembodied forms. It is worth noting

the sea change: all major trends of economics in neo-classical, institutional and evolutionary

schools now employ the notion of institution. Even if they define it in dissimilar ways, they

agree that individuals would be incapable of coordination if they shared nothing more than

simply judgments or calculative capacities. Institutional arrangements such as conventions,

cultural values and routines provide the individual with prosthetic tools. Some try to determine

the extent to which and the conditions under which an unequipped coordination (that is,

between agents endowed only with their cognitive capacities) is possible and efficient. This

epistemological tension is highly productive because it obliges those who assume the necessity

of the existence of institutional prostheses to be extremely rigorous in order to define the

conditions of their efficiency and usefulness. The idea is that humans create institutions to

4

This agreement has led to a non-problematization of Western markets which are assumed to be known or

described by economists and have therefore received little attention from anthropologists, whether F or S.

12

solve the problems encountered in the pursuit of their interests or in their will to survive and to

expand. In these approaches the social becomes an outcome, not a contextual nest surrounding

the economy or setting the conditions of its limits. The social is not substantively exogenous,

but formally endogenous to the economy.5

For the majority of economists there is nothing revolutionary in the assertion that

markets are social and human constructions, but they do see it as worrying. For them such an

assertion is not merely a critique but a challenge. They would like to answer the following

practical questions: Are some configurations more efficient than others? If so, what criteria

can be used to rank them? What are the most efficient conditions under which these

configurations can appear and be maintained? When economists – irrespective of the school to

which they belong – answer these questions, they start with a number of shared assumptions.

First, the fact of agreeing on the existence of institutions as devices required for coordination

implies that economic agents have creative and innovative capacities. Faced with practical

problems, economic agents, because they know that their cognitive capacities are bounded,

strive to create useful devices. The history of markets is the long history of the inventiveness

of human beings, capable of reflection and innovation. Secondly, the sometimes explicit and

often implicit idea is that these different proposed solutions are always competing with each

other in a selection process. This is clear in the case of evolutionary economics, but equally so

in the case of neo-classical economics. In the management of this selection process, national

governments and international organizations, usually advised by economists, play an essential

part. Left to itself, the selection process could result in blatantly under-efficient and even

socially unbearable situations. The twofold concern of economics is to unfold the variables

that could explain the different levels of market efficiency, and to urge governments to follow

the experts' advice and expertise in either designing the markets or in structuring national (or

transnational) economies.6

The analysis of institutions as socio-cognitive prostheses which facilitate efficient

coordination has naturally led certain economists to enter into the black box of human agents’

cognitive capacities and then to imagine and propose adequate institutions.

At the centre of formalist theses lay a genuine anthropology: the human being was

defined as a rational maximizer. In its different theoretical versions economics pursues this

anthropological investigation by studying individual agents’ real cognitive competencies. This

cognitive turn (Thévenot, 2006) highlights the importance of certain factors (internal or

external to individuals) which limit the efficiency of what Sahlins called economizing

behaviors. Human beings’ base is this very ability to optimize or at least to reach satisfying

solutions, but their calculative capacities and strategic competencies are bounded. By studying

these limits in greater depth, the economist-anthropologist is in a position to conceive of the

institutions and tools designed to offset these deficiencies, in a finer and more appropriate

way. We could compare the economist to a designer of prostheses and equipment for the

disabled, the nature of which is to optimize their behaviors but which do not always have the

means or the capacity. The anthropology as implied by economists’ practice, becomes more

ambitious, more complex and richer, since the economist thinks about the conditions in which

humans in society (and no longer humans considered as individuals limited to their somatic

envelope) can be “economized”.

In the terminology used in this paper, we can say that economics reaches the

conclusion that markets, conceived of as human and non-human arrangements (rules, routines,

etc.), have a dual status: they are natural, since they extend human nature and its optimizing

behaviors; and they are artifacts, since they are partly the outcome of human activity. The

economist “knows” that the nature of the human being is that of an optimizer but also that that

nature can be fully expressed only if certain conditions are met. The organization of economic

5

Some economists go beyond the simple recognition of the existence of these institutions. They also want to

analyse their emergence, transformation and maintenance: (North 1990); (Williamson 1985); (Williamson 1991).

6

On the role of economists as professionals, see Fourcade (2006).

13

activities shaped by norms and incentives, rules and routines, provides a satisfactory answer to

this paradox. In this perspective, the role of economics is threefold: furthering our insight into

human behaviours and their logic; analysing the obstacles preventing or impairing those

behaviours; and designing institutional frames which will eliminate or alleviate the obstacles

and enable economizing individuals to express themselves freely. Economics is, strictly

speaking, an anthropology in action; an anthropology for which human beings are by nature

economizing beings. It is to enable this nature to express itself fully that this anthropology

endeavors to design, and to help create, the conditions of economizing behaviours. Thus,

without diverging from the tradition opened by the formalists, it goes further. It explicitly asks

itself the question of economization, that is, of the nature of the mechanisms which enable

economizing behaviours to become explicit and dominant.

Economists’ contribution is essential for the programme that we wish to develop. First,

it is demonstrated that the economization of human behaviours is closely related to

institutional frames. This link is different from the one postulated by the notion of

embeddedness. It is to emphasize this difference that we have employed the concept of sociocognitive prostheses (obviously not used by economists). Institutions enhance and bring into

existence the competencies or appetencies which potentially exist in human beings and to

which they afford the possibility of being enacted. Economics is right to maintain, contrary to

the substantivists’ thesis, that in the narrow frame of certain conveniently designed

institutional configurations, economizing behaviours can be observed. The truth of such an

assertion depends only on the capacity to imagine, test and implement the institutions which

make these behaviours possible and effective (MacKenzie 2006).

Second, and this point stems from the first one, economics and more generally the

social sciences might play an important part in designing and setting up institutions.

Economization is linked to economics.7

Yet economics remains a prisoner of the highly restrictive hypotheses on which its

anthropology is based. The diversity of empirically observable human behaviours generates

doubts – at least from a methodological point of view – on the uniformity of economizing

behaviours: to economize, as emphasized by substantivists when they criticize the overly

narrow definition given by formalists (economizing as maximizing), could mean many

different things. We have to leave open the possibility that there is not only one single

profound human nature. It would perhaps even be preferable to give up the idea of a profound

human nature. Human nature is an historical achievement, a multi-sided path-dependent

process. Several possible anthropological trajectories exist and, with them, several modes of

economization.

I. 2.2 The New Economic Sociology: the Embeddedness Approach

Like the heirs of formalism, the successors of Substantivism seem not to be anthropologists.

Neo-substantivists are recruited from the ranks of the new economic sociology (NES) that was

developed in the late seventies and early eighties. One of the emblematic figures of the NES is

Granovetter with his seminal article (1985). (New) economic sociology is now a soundly

established institutionalized discipline with academic departments, handbooks and

professional organizations (Swedberg 2004). The heritage left by the substantivists was the

pivotal and polysemous notion of embeddedness.

For (new) economic sociologists, embeddedness as developed by Polanyi – “human

economy is embedded and enmeshed in institutions, economic and non-economic” (Polanyi,

1957: 250) – had two advantages. First, it established a productive link between the essentially

7

The nature of the relation may change according to the theoretical frame. Neo-classical economics would focus on

the design of incentives and of information circulation; evolutionary economics would choose as an entry point the

conception and implementation of appropriate routines; behavioural economics would be more oriented towards an

experimental approach.

14

European tradition of the sociology of economy, such as that of Durkheim, Weber and

Simmel, and heterodox institutionalist economics such as that of (Commons 1934) and

(Veblen 1953 {1899}).8 The concept also had the advantage of calling off the peace Parsons

signed with economists: You study the inside of the economy, I do society and the flows of

exchanges and interrelations between the two!” The idea of embeddedness rendered the

boundary between economy and society obsolete. Rather than being an independent subsystem within society, economy is enmeshed in it. For the incipient Neo-substantivists,

imagining two distinct disciplines makes no sense, for economic sociology is nothing but a

case of applied sociology. The new economic sociology is based on a prevailing

epistemological and disciplinary project: sociology is the queen of disciplines.

By making the concept of embeddedness a rallying cry, new economic sociology has

also managed to rid itself of one of the susbstantivists’ goals; hence, it no longer needs to

define what the noun economy or even the adjective (economic or economizing) mean. This

explains why, especially at first, economic sociology adopted a critical point of view in

relation to economics. Economics is based on the assumption (see 2.1) that a general definition

can be given of economic rationalities (and behaviours) as such, and that they can be

distinguished from non-economic behaviours. The new economic sociology rejects this

assumption. It sees the market as simply one site amongst many others, where the unrealism of

economics can easily be demonstrated and where the tools of sociology can prove to be fertile

(Granovetter, 2002). One consequence is that for the new economic sociology, notions like

production, exchange and consumption are non-problematic. Not because they are considered

to constitute the substance of economic activities but because, in certain circumstances, they

are taken for granted and/or enacted by actors themselves: they are institutionalized categories.

From a scientific point of view the objective is to study this enmeshing (or embeddedness)

itself and not the economy as such.

It is difficult to define the outline of this new economic sociology with precision. First,

this is because the notion of embeddedness has multiple meanings. Sociologists who refer to

it, more or less directly, develop distinctly different approaches because they depend on the

type of sociological framework used. Granovetter's embeddedness is different to that of

Dobbin, itself different from that of Di Maggio or Fligstein, to name only a few leading

figures (Dobbin, 1994; Fligstein, 2001; Granovetter, 1985; DiMaggio, 1994).

Second, it would be more exact to consider that the concept of embeddedness has

frequently been used as a rallying cry. It applies to research programmes whose ultimate

objective is to show that the economy cannot be removed from sociological analysis and that

economics does not have a monopoly on the analysis of the economy. That is why it is

appropriate in this section to take into account not only the new economic sociology (which

refers positively to embeddedness and to Granovetter’s founding work) but also all the

sociological approaches (even when they criticize the notion of embeddedness or when they

ignore it) which claim that the analysis of economic activities is simply a field of application

of sociological theory. Sociologists such as White (2001), Fligenstein (2001) and Bourdieu

(2005) have a critical or distant attitude to the notion of embeddedness. They nevertheless

share with the NES the conviction that sociologists should not change their analytical tools

when they study the economy. This approach constitutes a new sociology of economy (NSE),

as opposed to the sociology that left it up to economists to study the economy. To characterize

it, we can conceive of maintaining the notion of embeddedness and saying that the NSE’s

ambitious goal is to embed the social study of the economy in sociological analysis;

irrespective of the strategy applied, economics has to be embedded in sociology! In the

English-speaking world the new economic sociology, that of Granovetter, is the most active

component of this general movement.9 NES can be seen as the American branch of NSE.

8

For a presentation of an analysis of the decline of institutionalism see Yonay (1998).

The list of elements conceived of by sociologists to dissolve economic relations in the social grows by the day:

after culture, norms and interpersonal relations, it is now individual emotions or even collective spirit that give

capitalism the strength it needs (Boltanski and Chiapello 2006 ).

9

15

The diversity of approaches followed by the new sociology of the economy has

triggered many attempts to fight against this fragmentation and to maintain some degree of

unity.10 This is reflected in the recent proliferation of textbooks, readers and handbooks.

Dobbin's long introduction to his reader, The New Economic Sociology, is a good example of

integrative strategy (Dobbin 2004). He presents a concise and elegant synthesis of all the

explanatory strategies of economic sociology and simultaneously gives an overview of all the

sites investigated. Dobbin considers that embeddedness can be studied from four points of

view reflecting the vantage points of institutions, social networks, power relations and

cognition. For him, the concept of convention, i.e. the set of scripts followed by actors, is the

bridge connecting these four vantage points.11 He sees economic sociology as aimed at

analyzing how conventions emerge and are stabilized by tracking the complex web of relations

constantly being woven between institutions, cognition, social networks and power relations.

All those who know the growing corpus of works belonging to new economic

sociology will probably agree that these key concepts account fairly well for the wide diversity

of approaches and reasoning of this discipline. But what Dobbin highlights strikingly well is

the unity of what we call the new sociology of economy: there is no reason to change

analytical tools when one redirects one’s sociological curiosity from society to the economy,

because the latter is embedded in the former. Dobbin presents various empirical examples to

make the case that “social and economic behavior alike originate not in the individual but in

society”. 12

We agree with new sociologists of economy (and with Dobbin at least) to a certain

degree. First, they rightly overcome one of the most worrying limits of the substantialist

approach. There is indeed a categorical difference between substantivist anthropologists and

embeddedness sociologists. Without changing the main theoretical cartography of the

substantivist argument, sociologists dragged the explanatory framework from the exotic nonWest to the all too human West; the analytical tools to apply should not be changed when

moving from one to the other.

Secondly, the notion of embeddedness has freed sociological analysis. It has given it

both strong programmatic coherence (dissolve the economy in the social by all possible

means) and a large degree of latitude and inspiration. Sociological theory has taken up objects

that until now were monopolized by economics or other disciplines such as anthropology or

political science (for a mapping of these new territories annexed by sociology, see Smelser and

Swedberg, 2005). Moreover, the absence of a rigid and strict definition of the economy as such

has opened up new sites of investigation such as technical innovation and the relations it

assumes exist between markets, scientific research and public policies (Powell and Brantley

1993), intimacy (Zelizer, 2005), law (Swedberg 2003) (Stark 1996) (Edelman 1990) or art

(White and White 1965) (Moulin 1992) (Velthuis 2005), to mention only a few examples. This

obstinate work of critical conceptual deconstruction of the economy, on all fronts, has the

immense advantage of rendering visible and analysable the multiplicity of relations and

entanglements needed in the construction and reproduction of economic activities and

behaviours.

Thirdly, by emphasizing the fact that the economy is a social activity like all other

human activities, albeit a particular one, the sociology of economy, following in the footsteps

of the substantivists, has contributed powerfully to the recognition that there are multiple

forms of organization of economic activities, in general, and of markets, in particular. The

notion of embeddedness indicates, at least implicitly, that the economy is the result of

processes which have given it the specific and variable forms it has had at different times in

10

Several syntheses have been attempted, such as: (Smelser and Swedberg 2005); (Swedberg and Granovetter

2001); (DiMaggio 2001) (Guillen 2003) (Carruthers, B. and B. Uzzi 2000).

11 On the centrality of the notion of convention, but defined differently, see also Dupuy and al. (1989)

12 (Davis, Diekmann et al. 1994; Carruthers 1996); (Fligstein and Markowitz 1993) (Roy 1997). See also: (Fligstein

and Mara-Drita 1996);(Uzzi 1996; Swedberg 1997) (Carruthers and Stinchcombe 1999) (Carruthers and Uzzi 2000)

(Podolny 2001); (Le Velly 2002); (Velthuis 2003) (Duina 2004).

16

diverse societies. By deconstructing the economy (by means of general concepts such as

networks, power, fields or institutions), the new sociology of the economy has contributed to

the understanding that the economy has constantly been constructed and reconstructed. It has

thus suggested the importance of processes of economization – even if it has neither

pronounced the word nor addressed the problem as such. At the same time it highlights

implicitly the possibility, at least theoretical, of processes of dis-economization which are

supposed to denote all mechanisms through which, locally and for some time, the specificity

of economic behaviours and activities can be called into question.

The sociology of economy, with its ambition to embed the economy in society and

economics in sociology, nevertheless helps to push into the background a number of questions

that we believe are important.

a) The NSE tends to be interested in markets simply as one site amongst others where

the unrealism of economics (which implies at least some degree of calculative autonomy in

agents) and possibly the fecundity of applying social theory can easily be demonstrated

(Granovetter, 2002). By trying to show that markets can be deconstructed and analysed like

any other social reality, this sociology of economy has difficulty explaining and characterizing

their specificity and, in particular, their galloping expansion. What it misses is the progressive

construction of the specificity and force, celebrated or challenged everywhere, of what is

known as economic markets. By socializing everything, the NSE misses the issue of the

specificity of what we suggest calling economization.

b) As soon as we examine the process of economization (or, in NSE’s words,

disembedding/re-embedding), the importance of techniques and, more generally, of

materialities appears. From a theoretical point of view the sociology of economy focuses on

sociology’s favorite objects: networks and social relations, institutions, rules, conventions,

norms and power struggles. Yet the empirical research that it has inspired highlights the

decisive role played by techniques, sciences, standards, calculating instruments, metrology

and, more generally, material infrastructure. To build itself up and to last, withstand attacks,

reproduce and even change, a market is anchored in materialities which contribute towards

profoundly structuring and manufacturing the irreversibilities ensuring its perpetuation

(Granovetter and MacGuire 1998). The construction of markets is a socio-technical

construction, not a purely social one.

The paradox of NES, irrespective of the approach, is to have empirically shown the

essential role of techniques in the shaping and dynamics of markets, without providing

theoretical insights or analytical tools to understand their contribution.13 From this point of

view they are simply following Polanyi, who never hesitated to see the machine as one of the

founding events of self-regulated markets but never dreamed of integrating it into his analysis

of markets and their functioning (Polanyi, 1944).

c) To sum up: the notion of embeddedness has had positive effects but there is a

chance of it becoming almost meaningless due to overuse.14 Is it really true that the notion of

society is clearer than that of economy? Do we explain something by dissolving the object to

13

A recent article by Yakubovitch, Granovetter and MacGuire (2005) enables us to assess the devastating effects of

this absence of theoretical treatment of techniques and materialities. Wishing to explain the setting of electricity

prices, the authors reach the conclusion that pricing can partially be explained by technical and economic elements,

and partly by social relations (in its case, social networks). We could talk of an underdetermination of the economy

by society, reminiscent of the famous Yalta proposed by Parsons to economists: finally the autonomy of economy

and … economics is again conceded.

14 A good example of this danger is the impressive work of Zafirovski. In three books and tens of articles published

in a period of a few years, all he could write was how embedded the economic was in the social, without publishing

even a single account of a concrete market (Zafirovski and Levine 1997) (Zafirovski 2000) (Zafirovski 2001)

(Zafirovski 2002) (Zafirovski 2003). Whichever dimension of markets is discussed, we are told by the

embeddedness approach that it is social. Even the best critique of the embeddedness approach, which argues that

“[t]he concept of embeddedness posits that the world of the market exists apart from society even as it attempts to

overcome that divide” (Kripner 2001: 798) proposes that the market should in the end be “fully appropriated as a

social object” (ibid.: 801-02).

17

be explained in another general and controversial frame – society? The explanans being

fuzzier than the explanandum, this approach leaves us with a more complicated and trickier

unanswered question: what is society made of? Is it really satisfactory to limit the answer to

the usual ‘sociological’ list without mentioning, even in passing, socio-technical assemblages

and things that circulate from hand to hand? What would an economy be without commodities

and their physical properties and materialities?

To further our understanding of the part played by materialities in processes of

economization, we will now turn to a third current of analysis which has placed things and

their circulation at the centre of the analysis of processes of economic valuation.

I. 2.3 Circulation of Things and their Value

I. 2.3.1. The end of the great divides

In recent decades anthropology has made two changes which have led it to propose

new orientations for the study of the economy and economization.

First, disowning the previous problems, many anthropologists have decided to

question the validity of imposing the a priori trilogy of production, exchange and consumption

over objects of social research (for a striking example of such an approach see: J. Roitman

2005). More generally, summing up twenty years of research in cultural and material

anthropology, Descola rightly emphasizes that a comparative anthropology has to detach itself

from these categories and raise a more challenging question concerning the mechanisms

through which beings, whether humans or non-humans, are characterized and can enter into

relations of various kinds whose nature and distribution are a matter of research, not

assumption. Relations of production and consumption, which imply an ontological divide

between animate and inanimate entities, are simply one mechanism among others organizing

the transformation of beings and their mutual attachments (Descola 2005).

Second, the hypothesis that radical qualitative differences exist between Western and

non-Western societies have grown weaker, at least for a certain literature.15

Several reasons explain this trend. Note, in particular, the importance acquired by a set

of studies which have empirically highlighted the complexity and richness of the interactions

and relations between colonizers and colonized, and have thus contributed towards rendering

irrelevant the idea of a great divide. Within that research stream a particular role must be

granted to the post-Said, post-Orientalism literature. It engaged with Subaltern Studies in

South Asia, in which subjectification – and not just interaction or hybrid forms – was a major