Social and economic

advertisement

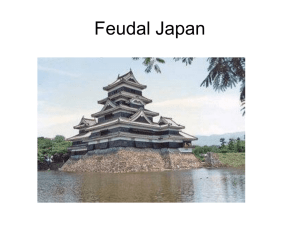

From G. Samson “ A Short Cultural History of Japan” Ch. 23 A. Economic and Social Conditions of the country Since the sakoku policy, Japan enjoyed a long period of political stability. Until the 1850s, Japan was free from any foreign intrusion; nor was there any foreign aid coming to the hostile tozama and ronin. Against this favourable background, Japan also entered a long period of economic and social prosperity. Agriculture was encouraged and cash crops were grown. There was a strong spurt of internal commerce. Many important transportation facilities, especially public highways like tokaido (東海 道), sanyodo(山陽道), nakasendo(仲仙道)and koshishukaido (甲州街道)were constructed and improved. In the Genroku period (元祿時代)of 1688-1703, there took place races among Tokugawas and daimyo for the construction of grandeur castles and palaces, which in turned stimulated the improvement of many superstructures. (see http://www.geocities.com/kwokyeunghk/index.htm for some of the pictures.) Originally the sankin kotai system aimed at exercising strict control over the daimyo to reduce their capacity of revolting against the Bakufu. The side effects of the system were the formation and accumulation of inflationary spiral. Upkeep of residence and mansions at Edo, expenses involved in traveling to and fro Edo, salaries to retainers and samurai, periodic subscription and contribution, and above all pleasure-seeking activities of the daimyo themselves while staying at Edo for half a year all needed money. This led to the increase demand for goods and over consumption. The samurai also posed a great problem to the society of Tokugawa. A long orderly period questioned the role the samurai played. Wars were no longer needed, what would be their new duties and functions? About 10% of the total population, they were mostly non-productive in economic sense. Rather than an asset, their subsistence became a burden to the Bakufu. If, however, nothing were done to relieve their difficulties, the pillar of the feudal society upon which the Tokugawa was built would be shaken. With the growth of domestic economy, cities began to spring up one after another. Concentration of ruling class in castle towns, efficient commercial framework, attractive town life and extreme poverty throughout the countryside contributed to the growth of cities. Amongst them Kyoto, Osaka and Edo (三都) were the most populous ones. Kyoto was a political, commercial and cultural centre, totalling 400,000 in the 17th century. Osaka was a great market place and a commercial centre for all central and western Japan, with a population of 300,000. Edo was the political and largest city in 1 Tokugawa Japan. In 1721 its population reached 500,000. one-sixth of all Japanese lived in towns. 2 By 1850, it was estimated that about Notwithstanding that Japan was a feudal society, the Bakufu did not adopt any intervention policy in commercial and economic activities. People from all walks of life were freely indulged in luxurious and pleasure-seeking lives. Commercial capital was accumulated. Currency were improved and in great circulation. Only when the government was in need of money did it adopt harsh measures against the merchant class, or regulate the market (e.g. the control of rice and commodity prices). So, merchants were the only class of people who benefited most in the Tokugawa regime. B. Problems existing in the countryside While the whole country seemed to enjoy the prosperity arising from the long period of peace, there were mounting problems in the countryside. Because of extreme poverty, natural disasters and poor harvest, small nuclear families grew in large number while large extended families reduced. Secondly, 1 there emerged in the countryside a rich class. Known as the rural entrepreneurs , they made their fortune at the expense of the majority peasantry and gradually became absentee landlords (if they lived in towns as chonin 町人) or modern businessmen lending money at a high interest rate. Moreover, an increasing number of peasants could not own their land to such an extent that they became either tenants or landless villagers. Few of them were to become the industrial labour working in cities and towns. Thus, there were rich landlords, tenants and landless peasants among the peasantry class. C. Living conditions of the peasantry The most suffering of the peasantry was the fluctuating prices of rice. No matters what efforts paid, peasants found that their destiny were put at the hands of the Osaka merchants who controlled rice wholesaling and retailing of the whole country. On the one hand, if harvest was good, a peasant could profit little because he had to pay a large amount of tax. If, on the other hand, harvest were poor, he and his whole family would be on the fringe of starvation. Generally speaking, peasants were the final victims of the country’s misfortune. Pressed by the merchants and moneylenders, the daimyo and the samurai transferred their burden onto the peasants. It is described by a contemporary source that officials and tax-gathers treated farmers “as a cruel driver treats an ox or a horse, when he puts a heavy burden on the beast, and lashes it mercilessly, getting all the angrier when it stumbles and whipping more violently than ever, with loud curses.” Peasants were often compared to seeds, like sesame, which were pressed for their oil, because “the harder you press the more you squeeze out.” 2 They were rich villagers who extended their economic bases from soil cultivation to non-agricultural pursuits such as retailing, money lending, manufacturing, marketing of commercial crops and managing of local factories. Coming from lower and humbler background, they were said to be more aggressive than the urban merchants 1 2 自 1726 年至 1828 年這一百年間,農民每人年平均收穫量僅合稻一石左右,所交的地租不僅有五公五民、六公四民,甚至有八 公二民。農民年終有餘糧者十無一、二。 3 For survival, peasants had to seek different ways. usurious townspeople. Some got into debt to the richer peasants or to Owing to intensive culture, which the increased demand for foodstuffs brought about, they had to buy manure, agricultural implements, horses, and oddments of clothing. If they got into debt, they would be on a steep road down to destruction. Some left for other districts, in the hope of making a fresh start. Some absconded and became vagrants. Some migrated to the towns where they could work as domestic servants or day-labourers. Abortion and infanticide were the common phenomena that occurred in the countryside by the middle of the 18th century. While their occurrence reflected the miserable conditions of the peasantry, it also meant insufficient supply of labours in the field, so farmers were known to buy children kidnapped in the large towns by the so-called “child merchants”. In so doing, they could secure labour supply without the expense of bringing up children. Urban migration also reached to a stage whereby laws had to be issued to forestall it from happening. These decrees known as hitogaeshi (人返)started as early as 1712 and were repeated at intervals until as late as 1843. But all failed. Different living conditions between the rural and the urban areas was the main factor that accounted for it. While peasants had to struggle ceaselessly for their survival, they, especially those who were young, found that the attractive, exciting and pleasurable city life offered them not only satisfaction but also a relief from oppression. As chonin, they were untaxed and received a money wage which they could spend as they chose. Because of urban migration, starting from about 1725, there was a decrease in rural population (or it may be safely assumed that the number of agricultural workers remained almost stationary even if it did not actually decrease). This in turn resulted in the corresponding drop in food supply and so fall in their income. It must be said that not all farmers were impoverished. expense of the majority of the poor ones. There were a few who prospered at the ‘For one man who makes a fortune, there are twenty or thirty reduced to penury.” The poverty of the peasants forced the majority poor to sell their land to the minority rich. This brought into existence of two new classes, one of persons who owned land which they did not farm, the other of persons who farmed land which they did not own. Tenant disputes arose when a landowner reproved his tenant for producing too much, because taxation increased in proportion to the yield, while the tenant objected because low yield meant no surplus for his own subsistence. Consequently, anomalies as such continued throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. In addition, there were frequent epidemics of pestilence, while famine raged from 1732 to 1733 and again from 1783 to 17873. Thus, it is not surprising to find that the population reduced by more than 1,000,000 in the years between 1780 and 1786. By coincidence, natural disasters were most serious in the period 1760-1786 when Tanuma Okitsugu was in reign and in the period 1828-1836 before the Tempo Reform. 3 4 In view of the peasants’ misery, the government leaders were not unaware of it. However, most of them proposed only neat ethical solutions of the equation of supply and demand. Peasant must work hard and respect their betters, merchants must be honest and content with small profits, and samurai must not be extravagant. With no help from the government and with increasing misery and misfortune, there found in the countryside a frustrated atmosphere. to improve their livelihood. Call for armed uprisings became their only outlet if they wanted From about 1750 peasant uprisings became more frequent. According to a finding made by H. Borton, there were 1153 uprisings between 1603 and 1867. However, its frequency increased with time.4 Sometimes they were mere peaceful demonstrations, sometimes they were angry revolts by armed mobs in their thousands. Towards the year 1800 the rioters became bolder and the samurai less inclined to resist. The causes of these peasant riots were varied and complicated. They might be responses to the oppression of merchants or outcry against the local authorities. They might be the result of loose political control due to the sankin kotai system. Natural disasters, overtaxation and maladministration of village officials were the immediate causes leading to their outbreaks. After 1730 tenancy disputes became more and more frequent. Although peasant riots were frequent, they did not pose a threat to the Tokugawa regime. It is because of their spontaneous nature, viz. an expression of resentment and a desire for removal of grievances. Once their grievances were removed, they would easily be dispersed. Never did the peasants aim at overthrowing the existing governments; nor did they have any future plans to create a new social order. So there were no leaders, ideologies and organization found in the peasant uprisings. Unlike the nomin ikki(一向一揆)or the monk-soldiers in the warring period, they had no social and religious affiliations among themselves. Nevertheless, from another perspective, the increasing number of peasant uprisings were also indicative of the fall of the Tokugawa authority. Suppose the peasants lived in peace and happiness and suppose the government took a good heed of them, how dared they revolt at the risk of their lives? D. Problems existing in the urban areas Long period of peace and stability resulted in the occurrence of many golden eras, the genroku jidai of 1688-1703 and the bunka-bunsei jidai (文政文化時代)of 1804-1830 being the typical examples. Amongst all four classes of people, merchants benefited from it. What were the factors which explained the rise of merchant class in Tokugawa Japan? The long period of prosperity and economic growth provided the most important explanation. Since all the townspeople, samurai in particular, needed money for their daily needs, needs which increased as the standard of living in cities rose owing to the lavish ways of the daimyo and the prosperous habits of the samurai, the traditional rice economy was totally unfit for the changing economy . At this juncture merchants played a decisive role, for they 4 The figure was 157 in the period 1603-1703; 176 in the period 1703-1753 and more than six each year in the period 1753-1868 5 not only fixed the rates of exchange from rice into money but also lent money to them to meet their needs. Meanwhile, the government itself was in great financial problems. Not just their debtors to the merchant class, they needed their expertise. Merchants’ knowledge of regulating quantities and prices of commodities were required and so they usually served in the government as bankers, purveyors and agents in the marketing of all goods. So one writer said: “The anger of the wealthy merchants of Osaka can strike terror into the hearts of the daimyo.” The rise of merchant class had far-reaching consequences upon the Tokugawa government. Their prominent role totally challenged the traditional Japanese social structure dominated by their military class, namely, the samurai. It was the samurai people of all classes looked up to. Their rise (and the decline of the status of the samurai) completely destroyed the foundation of the feudal society. still, merchants also gave rise to a carefree, materialistic and unpuritanical culture. Worse As found in the ukiyo(浮世繪), their prevalence also indicated the decay of a moral, frugal values taught by Confucianism. So the minds of the Japanese people were also changed. Troubled by the financial difficulties and deeply in debt from merchants, the ruling class had to look for different means of survival. A few daimyo encouraged industries in their fiefs, such as cotton-spinning and silk textile industries. But in doing so were they compelled to be engaged in commercial field and business upon which they once looked down. In general, the higher the rank, the less reluctant were they to do so. The majority daimyo resorted to traditional means: they borrowed money from their samurai, by the simple device of reducing their stipends at about one-tenth to six-tenths of the annual grant of rice. Indeed it was just a forced loan, at no interest, in perpetuity. In the long run, this practice eroded the old lifelong feudal relationship between daimyo and samurai, which had been based on loyalty and not on cash. 6 What happened to the ruling class at next level? Long period of peace turned most of the samurai into parasites. They should have carried their spear or led their horse in wartime, and hired merchants as servants. But they found all these futile and no longer needed. While their income had to be reduced because of the same financial difficulties that troubled their master, they had to seek other means of living. The most needy of them resorted to infanticide when they found their families growing too numerous. Others would adopt the son of a rich commoner if they could induce his father to pay handsomely enough for the privilege.5 This practice had profound effects on the society of Tokugawa. The samurai no longer prided themselves on the purity of their blood and the dignity of their ancestral name. Since the practice grew in frequency, towards the end of the Tokugawa regime it was quite usual for a commoner to purchase the rank of samurai. Such transactions were not unnoticed by the government. As early as 1710, decrees were promulgated calling attention to the importance of frugality and honesty in the military class. Contemporary literature contains many passages showing that the integrity declined with their fortunes and this double collapse brought them slowly but surely down in the esteem of the commoners6. They could no longer slash the commoners with their swords for fancied insults. Sometimes their swords were in pawn, with their armour and their ceremonial robes, and mostly they dared not resent affronts from merchants. As the main pillars of the feudal society, the Tokugawa of course did not want to see its collapse. Regulation of the price of rice and the currency measures were carried out to no avail. The traditional policy of exhorting samurai to be more frugal was equally useless. The government then endeavoured to fix rates of interest, with no real effect; then it resorted to the measure of cancellation of debts. In 1780 an edict ( or kien-rei 棄捐令) decreed that all debts incurred before 1785 by hatamoto and other liege vassals of the Shogun should be cancelled; and all debts incurred in 1785 and after were to be repaid in instalments so small that the creditors would certainly run into bankruptcy. Starting with the above economic and social changes, there took place in the Tokugawa society a fusion of classes or at least a blurring of that distinction between classes. Farmers became townsmen. Townsmen bought farms. Commoners and some farmers entered the ranks of samurai by adoption or purchase. Samurai surrendered their social privileges and became chonin for financial reasons. By about 1850 there was a regular tariff for the entry of a commoner into a samurai family, and many men of humble antecedents thus obtained samurai status, including “sons of low-class commoners, relatives of usurers; sons of blind men; criminals who had fled to Edo from their native towns; people expelled by their daimyo; excommunicated priests; sons of monks who had broken their vows, and even members of the pariah class.” Some of them rose to important positions towards the end of the Shogunate, becoming dependable officials. Indeed, the organization and formation of the new Meiji government of 1868 was in a great measure the work of them, Ito Hirobumi (伊藤博文) being one of the typical examples. 5 上層武士還可以剝削農民及商人及經營領地內專賣以自保;中層武士不僅變賣自己的財產,甚至出賣祖傳的世襲特權謀生;下層 6 當代作家如井原西鶴的十返舍一九以武士的墮落為平民嘲弄的對象。 7 It must be noted that people living in towns were not happier than the peasants. The mercantile organization of the chonin was almost as stiff and minutely regulated as the samurai. Their charters and their guild privileges rendered no free competition with the result that they were often able to hold the community at ransom, whether by putting prices up against consumers or by keeping wages down against workmen. Although the government had made several attempts to reduce their corpulence, they failed in the final end and it was the plain citizens, the small shopkeepers and the day-labourers who suffered.7 The see-saw battle between government and merchants made matters worse, and food riots occurred repeatedly in cities. The rioters raided shops and the houses of rich men, looting food and wrecking buildings. These risings occurred throughout the 18th century, and into the 19th. Two of them deserved mentioning. The first took place in 1787 as a result of the long famine of the Temmei reign (天明)in which there were incessant rain, volcanic eruption and unprecedented flood, the price of rice, 61 momme in 1785, rose to 101 in 1786 and 187 in 1787. There were raids not only in Edo, but throughout the country, from Kyushu(九州)in the west to Mutsu(陸奧)in the north-east. Another took place in 1837 when Oshio Heihachiro (大盬平八郎), a scholar, an Osaka official and a leading O-yomei(王陽明)philosopher, led a hungry mob attack Osaka and tried to set fire to the city. The riot was finally put down and Oshio took his own life. Indeed, it was found that between 1800 and 1868 the number of city riots was more than 200,8 showing the livelihood of the city dwellers was no better than that of the peasantry. E. Conclusion While the Bakufu was beset with the above problems, it must be noted that the situation was different in its strongest rivals, the tozama in the southwest, Satsuma, Choshu, Tosa (土佐)and Hizen (肥前). They had greater autonomy, utilized local industries and commerce without falling into the clutches of usurers and, most important of all, had preserved among their people the old feudal virtues of discipline and frugality. The Tokugawas did make several attempts to remedy the situation, but they did not succeed in commanding the allegiance of the daimyo and the discontented samurai, whose numbers were constantly swollen by financial distress, and whose loyalty was breaking under the strain of misrule. “The country was full of restless spirits, dissatisfied with their condition and thirsting for activity. Every force but conservatism was pressing from within at the closed doors; so that when a summons came During the Tempo Reform when the government tried to adopt anti-mercantile measures such as goyokin and removal of nakama, which led to the bankruptcy of a large number of Edo merchants, the Osaka merchants held up the supplies of all goods, and when they were ordered to sell the goods at a very low price, they sold only those inferior goods. They even stopped the delivery as a last resort. 8 During the Kyoho period (1716-1736), there were 10 city riots. The number increased to 60 in the Temmei period (1781-1789), and more than 45 in the Tempo period (1830-1844). There were 35 such riots in the last twenty years of the Tokugawa Bakufu. (Source from Yazaki Takeo) 7 8 from without they were flung wide open, and all these imprisoned energies were released”9, leading to the final collapse of the Tokugawa Bakufu. However, when we trace the origins of the social and economic changes, it is ironical “credited” to the success of the early Tokugawas in establishing a strict control system watching people at home and cutting the country off from the outside world, for its success provided the country with a long period of peace and stability leading to great social and economic changes. 9 from G. Sansom, p. 528 9