File

advertisement

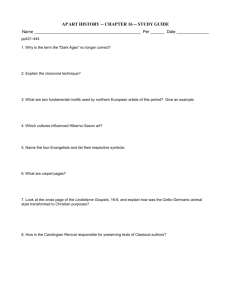

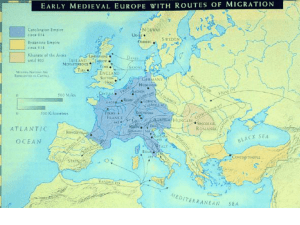

51 CHAPTER TEN EARLY MEDIEVAL ART Anglo-Saxon and Viking Art Key Images Golden buckle, from the Sutton Hoo ship burial, p. 314, 10.1 Hinged clasps, from Sutton Hoo ship burial, p. 314, 10.2 Purse cover, from the Sutton Hoo ship burial, p. 315, 10.3 Animal Head, from the Oseberg ship burial, p. 316, 10.4 The Celtic-Germanic style, with its complex interweaving patterns, was a result of the migrations that followed the fall of the Roman Empire. The primary medium of the Celtic-Germanic style was metalwork and jewelry. These objects were skillfully executed and often made out of gold or silver with inlaid stones. This style is often referred to as ″animal style″ because of the stylized animal forms that were frequently used during this period. The principal medium of the animal style was metalwork. Hiberno-Saxon Art Key Images Symbol of Saint Matthew, from the Book of Durrow, p. 317, 10.5 Cross page, from the Lindisfarne Gospels, p. 318, 10.6 St. Matthew, from the Lindisfarne Gospels, p. 319, 10.7 Ezra Restoring the Bible, from the Codex Amiatinus, p. 319, 10.8 Chi Rho Iota page, from the Book of Matthew (1:18), from the Book of Kells, p. 320, 10.9 ● During the early Middle Ages Irish monasteries became centers of learning. In the scriptoria of the monasteries, religious texts were copied and illuminated. ● The Hiberno-Saxon style combines Christian, Celtic, and Germanic elements. ● Several factors contributed to the development of the Hiberno-Saxon style, including the isolation of the Irish, the sophistication of their scriptoria, and the desire of the monastic communities to spread Christianity. ● The Hiberno-Saxon manuscript style reached its peak with the Book of Kells, the 52 most elaborate codex of Celtic art. The book takes its name from the Irish monastery of Kells where it was located from the late ninth century until the 17th century. Carolingian Art Key Images Equestrian Statue of a Carolingian Ruler, p. 321, 10.10 Christ Enthroned, from the Godescalc Gospels (Lectionary), p. 322, 10.11 St. Matthew, from the Gospel Book of Charlemagne (Coronation Gospels), p. 322, 10.12 Portrait of Menander, p. 323, 10.13 St. Matthew, from the Gospel Book of Archbishop Ebbo of Reims, p. 323, 10.14 Illustrations to Psalms 43 and 44, from the Utrecht Psalter, p. 324, 10.15 Front cover of binding, Lindau Gospels, p. 325, 10.16 Odo of Metz, Interior of the Palace Chapel of Charlemagne, p. 326, 10.17 Abbey Church of Saint-Riquier, p. 327, 10.19 Westwork, Abbey Church, p. 328, 10.20 The period of Charlemagne and his successors dates from ca. 768 to 877. Under Charlemagne there was a ″Carolingian Revival″ in which Charlemagne proclaimed a renovation imperii romani, with a renewed interest in the Classical past. The art of this period combined ancient classicism with native northern European artistic traditions. This can be seen in Carolingian manuscript illumination which combines ancient classicism and the linear dynamism of the Celtic-Germanic style. Charlemagne recognized that the monasteries were essential to the promotion of learning and culture, and he encouraged the collection and copying of ancient works. Toward the end of the eighth century, Charlemagne constructed his imperial palace at Aachen. Modeled after Constantine’s Lateran Palace in Rome, Charlemagne′s palace included a basilica linked to the Palace Chapel, which was based on San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. The palace was designed by Odo of Metz, who also incorporated a westwork into the western entrance of the palace. The monastery plan at St. Gall, Switzerland, reveals the self-contained features of a medieval monastic community. Ottonian Art Key Images Interior, looking east, Church of St. Cyriakus, p. 331, 10.22 Exterior, Abbey Church of St. Michael′s, Hildesheim, Germany, p. 332, 10.24 Interior, with view toward apse, Abbey Church of St. Michael’s, Hildesheim, Germany, p. 333, 10.25 Doors of Bishop Bernward, Hildesheim Cathedral, p. 334, 10.26 53 Accusation and Judgment of Adam and Eve, from the Doors of Bishop Bernward, p. 336, 10.28 Temptation and Fall, from the Doors of Bishop Bernward, p. 336, 10.29 Column of Bishop Bernward, Hildesheim Cathedral, p. 337, 10.30 Christ Blessing Emperor Otto II and Empress Theophano, p. 338, 10.31 Otto III Receiving the Homage of the Four Parts of the Empire and Otto III Between Church and State, from the Gospel Book of Otto III, p. 339, 10.32 Jesus Washing the Feet of St. Peter, from the Gospel Book of Otto III, p. 339, 10.33 St. Luke, from the Gospel Book of Otto III, p. 340, 10.34 The Gero Crucifix, p. 341, 10.35 Virgin of Essen, p. 342, 10.36 Following the death of the last Carolingian monarch in 911, the German kings of Saxon descent consolidated political power in the eastern portion of the empire, establishing a new Ottonian dynasty. The greatest of the Ottonian kings was Otto I. Germany was the cultural leader of Europe during the Ottonian period, from the midtenth to the early eleventh century. The Ottonian emperors relied on the church to strengthen their rule, and this, in turn, led the Ottonian dynasty to build new churches and decorate them lavishly. Ottonian religious art reflects the influence of Byzantine art combined with an ″expressive realism.″ There is also an increased interest in large-scale sculpture during this period. The bronze doors of the Hildesheim Cathedral are considered by many scholars to be the first monumental bronze sculptures created with the lost-wax technique since classical antiquity. Key Terms/Places/Names cloisonné inlaid niello animal style horror vacui Sutton Hoo manuscript illumination scriptoria colophon Codex Amiatinus Charlemagne turrets westwork tribune monastery portico module crypt 54 typology reliquary Discussion Questions 1. How does the treatment of the human figure in Hiberno-Saxon art differ from the treatment of the human form in Greece and Rome? 2. Discuss the innovations in church architecture found in the Abbey Church of St. Riquier, France. 3. How is the Carolingian Revival responsible for preserving texts of Classical authors? 4. Identify two artistic sources for Ottonian manuscript painting and discuss how these sources combined to form a new style of illustration. Resources Books Backhouse, Janet, D.H. Turner, and Leslie Webster. The Golden Age of Anglo-Saxon Art, 966–1066. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984. Beckwith, John. Early Medieval Art: Carolingian, Ottonian, Romanesque. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974. Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983. Cirrker, Blanche, ed. The Book of Kells: Selected Plates in Full Color. New York: Dover, 1982. Horn, Walter W., and Ernest Born. Plan of Saint Gall: A Study of the Architecture and Economy of and Life in a Paradigmatic Carolingian Monastery. (3 vols.) California Studies in the History of Art. Berkeley: UC Press, 1979. Mayr-Harting, Henry. Ottonian Book Illumination: An Historical Study. (2 vols.) New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. DVDs Medieval Siege. (1999). NOVA. 60 min. The Book of Kells. (2006). Kultur Video. 60 min. The Vikings. (1999). NOVA. 56 min.