Timothy J

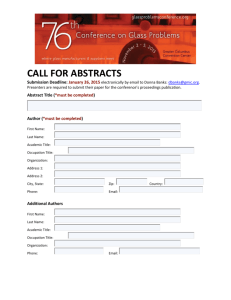

advertisement

Timothy J. O’Brien Buzzanco Fall 2006 Mary A. Renda, Taking Haiti: Military Occupation & the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915-1940. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Mary A. Renda, a history professor at Mount Holyoke College, won the Stuart Bernath book prize for her study Taking Haiti: Military Occupation and the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940. The prize is given by the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations for an author’s first book. It also won the Albert J. Beveridge Award which is presented by the American Historical Association. Because Renda’s monograph closely examines culture she used more mainstream sources than the average diplomatic history or foreign policy book usually would. In addition to manuscript collections she utilized films, plays, novels, newsreels, soldier’s accounts, oral military history collections, and an extensive amount of secondary literature. She also conducted a small amount of personal interviews. The book begins with a lengthy introduction that relates the immediate one hundred years of Haiti history leading up to the occupation. The rest of the overly detailed introduction almost obscures her research question which is understanding the occupation as an event in the cultural history of the United States. Renda argues that the American occupation of Haiti came out of a culture of paternalism and imperialism. Renda breaks her book down into two sections, the occupation and the aftermath. The first section looks at how paternalism, racial attitudes and conditions in the United States, male gender identity, homosocial behaviour, the individual soldier’s upbringing and background, military training, the formation of an American identity among immigrants, and the reality on the ground all affected the outcome of the military occupation. Because it is a cultural study Renda is trying to understand how specific American cultural forming events influence and explain how the U.S. military was acting and reacting on the ground in Haiti. She relates how the military combated the Haitian Cacos who were fighting to rid the island of the U.S. occupiers. Specific incidents of brutality by the U.S. marines, forced labor of Haitian peasants, and the dehumanization of black Haitians by white marines bring the story to life and highlight the despicable consequences of a large powerful country inflicting its will on a small undeveloped nation. The second half of the book traces the “path of Haiti’s career in the United States.” This portion of the book is of particular interest to readers with an interest in twentieth century African American history. Paternalism, exoticism and the commidification of Haiti in the American public are stripped down, and turned every which way in order to try and understand how the occupation was absorbed by the U.S. populace. The narrative is most engaging when Renda uses popular culture to show how Americans viewed voodoo, mysticism and zombies that they associated with Haiti. The zombie was originally based on Haitian material and became a popular image in a young and rapidly growing American film industry. Renda concludes that the military occupation came from the American culture of imperialism. By 1915 when the occupation began, this manifested itself as a discourse on interventionist paternalism. Ultimately the American policy of interventionist paternalism in Haiti fell somewhere in the gray area between success and failure. While it is a tricky business trying to gauge this brand of paternalism on both the occupiers and occupied, 2 Renda argues that it did leave a distinct impression on both. In the U.S. this imprint was visible on foreign policy, as well as the politics of race and gender. 3