Corresponding Member of the Romanian Academy

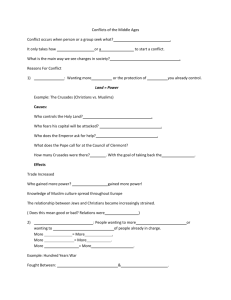

advertisement

THE ROMANIAN ACADEMY THE HISTORY INSTITUTE ‘GEORGE BARIŢIU’ CLUJ – NAPOCA Candidate for a doctor’s degree: Mircea- Dumitru MOTOGNA THE ORTHODOX MONACHISM FROM MARAMURES AND NORTHERN TRANSILVANIA UP TO THE BEGINNING OF THE 19TH CENTURY PHD THESIS (SUMMARY) Scientific guide: Prof. Univ. Dr. Nicolae EDROIU Corresponding Member of the Romanian Academy Cluj – Napoca 2007 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… The PHD thesis is entitled ‘The Orthodox Monachism from Maramureş and Northern Transilvania up to the beginning of the 19th century’ and in its contents I have spoken about those orthodox hermitages and monasteries which lasted from the beginning of Christianity up to the beginning of the 19th century, on whose territory lay the canonical jurisdiction of the locum tenens Pahomie of the patriarchal monastery from Peri, of the county Maramureş (1391), that is the regions : Maramureş, Sălaj, Ardud, Ugocea, Bereg, Ciceu, Unguraş and Bistra. The geographical area of research includes the Northern part of Someşul Mare and the part of the historic Maramureş which is situated on the right side of the Tisa river and which belongs now to Ukraina. The oldest history of romanian monachism still lies hidden in the darkness of the first millenium. Regarding the clerical institutions and the monastic ones, we do not have any clear news since the early Christianity and the axiomatical beginning of the formation of the romanian nation. The foundation acts, the acts regarding the datum of apparition, documents regarding the inventories, the inner order, the givers, the bead-rolls with survivers, the landed acts, all these are totally missing. Each attempt of historiographic recomposition refers to the origins. A well-done bibliographical research shows us which were the real beginnings of romanian science that deals with the study of monasteries. The hermitages and the monasteries from this geographical area of research were few, they were built especially thanks to the monks’devoutness and faith, to the priests of the chrism or even to some believers. The majority of monasteries mentioned in this work appear in other writings too – more or less – others do not, and now are being brought new evidences in this regard, including archeological discoveries like those which were found at the monastery Bîrsana this year, but not only. The work contains five chapters, preceded by an introduction, followed by conclusion, bibliography and annexes, as follows: Chapter 1. The socio-political status of the romanians from Maramureş and the Northern Transilvania up to the beginning of the 19th century. Chapter 2. The church organization of the romanians from Transilvania and Maramureş up to the 18th century. 2 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… Chapter 3. Features and characteristics of the orthodox monachism from Transilvania and Maramureş up to the beginning of the 19th century. Chapter 4. The hermitages and monasteries from Maramureş and Northern Transilvania up to the beginning of the 19th century. Chapter 5. The cultural size of the monachism from Maramureş and Northern Transilvania. The work ends with some pages of conclusion, selective bibliography and annexes. *** The romanian slot from the Northern part of the Someş river has made acquintance of an evolution which frames it in the typical becoming of the Mediaeval Era. This evolution is connected to the insight of the Hungarian regality in this territory and to the historical trajectory which this event has conferred upon the transilvanian slot up to the Contemporary Era. Anonymus speaks about the existence of some romanian political crystallizations or a combination between romanian and slav political crystallizations which the hungarian horsemen submit. Anonymus’ chronicle was elaborated between 1150-1200; in that period existed several ‘countries’: ‘The Country of Maramureş’, ‘The Country of the Duke Menumorut’ and ‘The Country of Gelu’, but about the Northern Transilvania we do not find too many data. The first embryos of some future counties are certified at the beginning of the 11th century : in 1166 is certified the Solnoc county, which was later separated in four counties : Dăbâca, the Outside Solnoc, the Middle Solnoc and the Inner Solnoc. In 1181 is certified the County of Sătmar. Before the arrival of the Hungarians, the romanian hospodars had their abode towards North, at the edge of Mramureş, on the valley of Bîrjava. The statute of the romanian high societies was typical for Transilvania, as they were represented there after the 9th century by the following cathegories: founders, hospodars, aristocrats and soldiers. This region lead by a hospodar was certified in 1299, then in 1303 is mentioned the hospodar Nicolae and in 1326 his son Ştefan, after that, we actually assist to a division of Maramureş in two parts lead by hospodars, each of these two parts being divided in other small districts lead by their founders. 3 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… In Maramureş existed seven districts lead by their founders, valley districts : the district of Cuhea, the districts from Cosău, Mara, Câmpulung, Tabor, Bîrjava and Bedeu. Although Maramureş contained seven valley districts aproximatelly, each of them made up of several village districts again lead by their founders, it remains a model of the romanian socio-economical and political structure, kept even after the superposition of the county. Unlike the valley district lead by its founders, the region of Maramureş lead by a hospodar, a kind of hereditary possession, was an elective institution, with the tendency of becoming hereditary. Regarding the romanian demographic element, we may say that it is processed in the historical documents, and it illustrates a massive romanian ethnical preponderance in the Northern part of Someş. In this period, the first cities have been certified: Satu Mare (1230), Baia Mare (1329), and Baia Sprie (1329). The citadel Chicho (Ciceu) appears in documents on the Valley of the Someş river, around 1304, the citadel of Chioar was towards North-West probably built in 1270-1272, and the citadel Hust will be built in 1350. Three citadels are documentary mentioned in the county of Sătmar before the Mongolian invasion: Satu Mare, Ardud, Medieşu Aurit, and the Citadel Ardud (castrum Ardud) is mentioned in 1215. The citadel Crasna (castrum Karaznay) is also mentioned before 1241. Inside the county The Inner Solnoc is known the citadel Cuzdrioara. In the area of Maramureş are cited the citadel Nyalab in 1351 and the citadels Bea War and Rona in the 15th century. An important episode in the history of the romanians from the North-Eastern part of the Someş river is the one that presents the establishment of the military border in Năsăud, in March 10th, 1761. One of the reasons for founding a regiment there was to stop the Romanians from Transilvania from migrating towards Moldova. The area from the Northern part of Someş will be reached by the disturbances which affected Transilvania in the second half of the 18th century. The emissaries of Sofronie from Cioara arrive in that area around 1760. The 18th century, by means of the illuminist ideology has favoured the cultural raise of the Romanians from Ardeal and one of the most remarkable events from the Romanians’ histoy of this century was the Supplex’s motion. A nation with old christian traditions, with a strong faith which had deep roots in history, roots which can be traced back until the 2nd-3rd centuries, a nation who around the 4 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… year 900, appears organized in strong political and military systems, having as leaders dukes, founders, hospodars with entrenched citadels, with hard-set places, with churches, with an advanced economical and social life, it definitely had a church organization too, lead by bishops. Each hospodar wanted to have in his ‘citadel’ a bishop, whose profession was to shepherd over the priests and believers, inside the boundaries of a political system governed by that hospodar, and such rural districts existed at Dăbâca, Biharia, Alba Iulia (Bălgrad) and at Bogdan Voda’s Cuhea. After Transilvania was occupied by the hungarian kingdom, confessionally fronted towards the Romanian Church, this institutionally extended in Transilvania too, founding monasteries and bishoprics. The Great Schism from 1054 added a religious conflict to the ethno-political conflict which arised from the conquest of a region lead by a hospodar. This is how an era of religious intolerance began and lasted from Ştefan the Saint to Sigismund. Gradually, the orthodox bishoprics from the ex-residences of hospodars have been substituted by catholic bishoprics: one in Biharia, moved to Oradea in 1092, another in Tăşnad soon moved to Cluj, and in 1092 at Bălgrad (Alba Iulia). We must keep in mind that after the peasants’ rebellion in 1437, the well-known ‘fraternal union’ was glued, it was called ‘Unio trium nationum’ and it was composed by hungarian noblemen and the leaders of saxons and szeklers. The deal had from the beginning a social meaning, of hierarchy, being reformed against peasants. In spite of these repressive measures and in spite of the reduction to the state of ‘religio ilicita’, the Orthodox Church continued to manifest itself, to be present in churches and monasteries by means of its men-servants, priests, arch-priests, hegumens and hierarchics. There was a monastery in Maramureş in the 14th century, in the village Peri (today Hruşevo, in Ukraina). In August 13th, 1391 the Patriarch Antonie the IV th (1389-1390 and 1391-1397) declared the Monastery Peri patriarchical monastery. The year 1391 is a representative moment in the lives of the Romanians from Maramureş, a presumptuous achievement of the Baliţă and Drag brothers in their fight for political and church independence against Hungary’s catholic kings for the custody of the romanian national being and of the orthodox faith. Between Transilvania, Ţara Româneasca and Moldova existed strong and lasting connections regarding both the national and the religious idea. 5 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… Along the centuries, the church contacts have been determined by three elements: 1. On both sides of the Carpathians lived our people, not only with the same blood but also with the same religion- the orthodox one. 2. From the 14th century the Northern Orthodox Church hierarchically depended on the metropolitan church from Ţara Românească and Moldova. 3. The gentlemen and the landowners from the romanian principality possessed lands in Ardeal, where they built churches and monasteries which they upholded, where they put priests and monks and even hierarchics. Regarding the religious life of the Romanians from those lands, their mastery by the hospodars of Moldova had a special importance. It seems that in the village Vad, situated near the citadel Ciceu, existed an orthodox monastery, since the 14th century. Ştefan cel Mare is the one who set up the bishopric from Vad, and put there an orthodox bishop. The reason for which Ştefan cel Mare did so, was that he needed not only a military and political support, but also a religious one. Regarding the problem of the origins of Transilvania’s metropolitan church, our old historians expressed different opinions, but it is certain the fact that Mihai Viteazul, hearing about the precarious materialistic state of the metropolitan church, he built a church -monastery- in Alba Iulia, near the walls of the citadel, which was used after that as a cathedral and metropolitan residence. A new historical stage for the evolution and reinforcement of the metropolitan church took place during the mastery of the great hospodar upon Transilvania and Moldova. From a religious point of view Mihai Viteazul has followed the strenghtening of the old hierarchical links between the metropolitan church of Transilvania and metropolitan church of Ungrovlahia, the emancipation of the romanian priests from serfdom, but he was also preoccupied of the raising of moral state of the romanian orthodox clergy. We must take into account the fact that once with Mihai Viteazul came in Transilvania many priests and monks from Ţara Românească, whom helped him in his actions, thus the archimandrite Serghie of Tismana was named bishop of Muncaci and he was able to dart that bishopric from the catholic influence, but also from the one of the metropolitan church from Kiev. From the 14th century we have the oldest information about the church life from Maramureş, comprised in the nobiliary diplomas, where are recorded religious names of places and of priests. Later will be added notes from the books of cult and official markings. We mention the fact that sometimes the same bishop lead the bishopric of 6 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… Maramureş and the one of Muncaci, and when the region of Maramureş had no bishop of its own, the bishopric of Maramureş was lead by metropolitans from Alba Iulia. Confessionally speaking, the period 1541-1700 is characterized by the reinforcement of the Protestant dominations (Lutheranism, Calvinism and the United Church). The diet of Transilvania institutionalizes Lutheranism (Turda 1550), Calvinism (Aiud 1564) and the United Church which, alongside catholicism much diminished in power and role as a consequence of the abolition of bishoprics and as a consequence of nationalization of lands, these will form the four accepted religions. The orthodox religion continues to be a ‘religio ilicita’, persecuted, and the believers continue to be tolerated. The calvinist proselytistic action pursued like the catholic one, the ‘hungarianization’ of the orthodox Romanians, by attracting them to Calvinism. In the 17th century, the anti-orthodox and anti-romanian campaign was harder than in the previous century, and it met several forms and burden-some conditions. After 1688, the new political situation lead to essential changings even inside the romanians’ church life. By attracting the romanians to the union with the church of Rome, it was pursued the growth of the number of the catholics and implicitly the growth of the political role of the catholic representatives in the Diet – on the one hand, and on the other hand the weakening of any kinds of links with the orthodox romanians from Ţara Românească and Moldova. Even if accepted by the clergy from the Supreme Forum of the Church – signer of the testimony Book from October 7th , 1698 and institutionalized by the king by means of the two leopoldine Diplomas from 1700 and 17001, the union was just a partial success, the majority of the Romanians continuing to be orthodox. Although disputed even during the negotiations, the Union has started an entire resistance movement which developed from negation and protest to revolt. Great fights for the Orthodoxy took place in 1744, when the priest Visarion Serai went from Carloviţ to Banat and then to Transilvania, fights which continued with a greater force between 1759 – 1761, under the guidance of Sofronie. All the attempts of the habsburgic government, during 60 years, to convert the Romanians from Transilvania to the union with the catholic church, proved to be in vain. Different methods have been used : persecutions, beatings, arrests, death convictions, lurings, promises of equal situations with the ones of the four accepted religions, abusive passings of entire villages as united, the exile of the orthodox persons from their villages so 7 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… that in their place to be brought the united ones, the ablation of the churches, the military and administrative power. All the hue and cry mentioned above, persuaded queen Maria Tereza to give in 1759 the edict of religious tolerance and to name a bishop for the orthodox Romanians from Transilvania – this being Dionisie Novacovici – and this is how the Orthodox Church from Transilvania has institutionally remade itself. We can speak about the orthodox monachism from Transilvania only by taking into consideration all these political, social and church factors. Regarding the genesis of the christian monachism, the majority of the historians agree that it took place in the second half of the 3rd century in Egypt, Palestina, Syria and Mesopotamia. Monachism has always been a true reality of the church and it is an authentic form of church life, in other words, monachism is an integrant part of the church just like the parish, neither above the parish, nor outside the church. Many christians from the 3rd and 4th century have dedicated themselves to this life style, and among them: Pavel from Teba, Pahomie the Great, Antonie the Great, Ilarion, Macarie the Egyptean, Teodosie and many others which play an important role in the church life and may be considered the founders of monachism. The real community life was to be founded by Saint Pahomie the Great who built the first monastery where the monks lived their lives jointly at Tabennisi, after the year 315. St. Pahomie gave 194 rules for his monks. In Small Asia, St. Vasile the Great carried on a special activity regarding the organization of monachism and drew up in 362, 55 great rules and 318 small rules. St. Vasile the Great’s rules have been well perceived by the orthodox monachism and they represent the foundation of the statutes of the most important orthodox monasteries. Up to the 5th century, the Supreme Forum of the church from Calcedon (451), in which monachism was for the first time brought into discussion as well as his place in church, monachism existed as a society of pious people who were independent from the church jurisdiction. This Supreme Forum of the church gave to monachism the canonic base over which to organize itself. Monachism existed on the territory of our country from its beginnings, being brought once with the learning and the christian spirituality which cannot be separated from it, and this monachism is older than the one of our slav neighbours. 8 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… In Transilvania just like in the other two romanian provinces the monastic life existed in organized forms even from the beginning of the second christian millenium. Transilvania has known a different historical development from the one that existed in Ţara Românească and Moldova. Due to the foreign domination, which lasted up to the end of the first world war, the Romanians from Transilvania could not make up an independent political organism. This thing has strongly marked the development of monachism and its nature which was missionary and defensive rather than one of preservation of the straight faith, in a period when the Orthodox Church from Ardeal was attacked by the calvinists and by the catholics. With probable origin in the first christian millenium, orthodox monachism from Transilvania has increased in proportion and value in the first eight centuries of the second millenium, so that the number of the hermitages and monasteries has reached almost 200. Due to the location of these monasteries, almost always in isolated places, far from the villages, the news about their existence and activity were made public late, rarely officially recorded, thus the documentary information which certifies them are few and isolated. This, in case they have not remained anonymus. The fact, associated to the restrictive frame imposed to the orthodox monachism , tolerated at the limits of the law and to the conditions of small rural hermitages with limited resources and minimum chances of assertion beyond the borders of the villages in which they were, explains in part, the difficulty of identifying the chronological moment of the foundation and of the temporal segment in which they have activated. The chronological moment of the foundation of some establishments was certified by retrospecting them to the religious inscriptions, to objects about which it is known to have belonged to them, to notes from the books, to official documents or by accrediting the tradition as a document. Several establishments had an existence certified only by tradition, oral history. We know that they existed, thus they were canned in the system of heritable values, assimilated by the oral history of the villages as evidences of the ancientness and insistence in orthodoxy. The substitution of the halidoms and of the orthodox church institutions with new ones, catholic ones can be traced almost everywhere in Transilvania. Among the oldest monasteries from Transilvania we have Meseş (1165), then in 1185. Meanwhile, there existed orthodox monasteries between the borders of the hungarian 9 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… feudal kingdom, such as the one from Oroszlanus, another was the monastery HodoşBodrog (Arad) (1177), but her origin seemed to be from the 11th century. In 1192 was recorded the ‘founder’s monastery’(monasterium Kenez) in the area of Bihor, later met in the documents of the 13th century, certainly a foundation of an orthodox romanian founder. Other documents mention a whole series of monasteries on the valley of the river Mureş, from the 12th –13th century, but today there is nothing left of them. Besides the monasteries mentioned above, several settlements built on the cliffs have been discovered: at Moigrad, Jac, Creaca and Brebi in the area of Sălaj. All these discoveries certify the existence of the monastic life on these lands even from the first christian centuries, but to these we may add other evidence inspired from the names of certain places, which uphold the romanian monachism’s ancientness: Chilia, Chilioara, Călugărea, Călugăreni, Râmeţ, Schitu, Mănăstirea, ‘La Mănăstire’, ‘Valea Mănăstirii’,’Valea Călugărului’, ‘Podurile Mănăstirii’, ‘Movila Călugărului’, ‘Buza Călugărului’, ‘Călugăr’, ‘Faţa călugărului’, ‘Drumul Călugărului’, ‘Gura Râmeţii’,’Valea Remetea’etc. Once with the state organization of the romanian provinces, the first monastic settings appear and they last over the centuries. The monasteries from Transilvania, humble as they were, became residences for some hierarchics. There, the bishops used to study and they prepared themselves for becoming priests, they kept the Supreme Forum of the Church and they ordained priests and deacons. Such monasteries, episcopalian residences were those from : Ariniş, Barania, Bârsana, Bichigiu, Biserica Alba, Bixad, Budeşti, Ciumuleşti, Cuţa, Drăgoieşti, Giuleşti, Habra, Moisei, Păduriş-Strâmba, Peri, Petrova, Uglea, Vad, the last one being an episcopalian centre, which consisted in 11 bishops. In some villages existed several hermitages, as it happened in the village Chiueşti, near Cluj, where in the 18th century existed five hermitages, that is why in many cases the name of the monasteries are improper, as they are actually hermitages, but I have widely called them monasteries. The forth chapter of this work is the most complex and it is full of information about the monasteries that existed in Northern Transilvania and Maramureş up to the beginning of the 19th century. In this chapter we have presented the names of the monasteries, the booking, the founders, the sactification, the living beings, the activities, where possible we have shown the chronological moments in which they have functioned. 10 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… We enumerate here only the names of the the monasteries which existed in this area, since, about them we have written in the work itself. These monasteries are: Ariniş, Barania, Bălan, Bârsana, Bichigiu, Biserica Albă, Bixad, Blaja, Bogdan Vodă, Boiereni - Valea Rohiiţei, Botiza, Brebi, Buciumi, Budeşti, Călineţi (Maramureş), Călineşti (Satu Mare), Căşeiu, Chechiş, Chilia, Chiueşti - Dealul Podului, Chiueşti - Valea lui Ivan, Chiueşti - Valea lui Vlad, Ciceu - Poieni, Ciocmani, Ciumuleşti, Copalnic, Cormaia – Sângeorz - Băi, Crişăneşti, Curtuiuşu Mare, Cutiş, Cuţa, Dolheni, Dragomireşti, Drăgoieşti, Feldru, Giuleşti, Groşi - Habra, Ieud, Lăpuş, Lăscâia, Leurda, Mara, Merişor, Moisei, Negrileşti, Păduriş - Strâmba, Păltineasa, Peri, Petrova, Popteleac, Rebra, Rebrişoara, Rona de Jos, Rozavlea, Rugăşeşti, Santău, Săcel, Săliştea de Sus, Sălsig, Sârbi, Stobor, Şimişna, Şomcuta Mare, Tresnea, Ţeghea, Uglea, Vad, Văgaş, Valea Căşeielului - Schitul Fanti, Valea Căşeielului, Vălenii Şomcutei, Vetis, Vişeul de Sus, Zagra. During the 18th century, our monasteries have been real points of resistence in front of the propaganda lead by the kings from the Habsburg dinasty, with the purpose of attracting the Romanians to the union with the Catholic Church. Although the monasteries from Transilvania have not been imposing from an architectural point of view, or immovable as structural-hierarchical organization, or as a number of living beings, they imposed themselves by means of the role they played. Here is a very cruel order, given by this role to its subalterns in June 13th, 1761: “The wood monasteries must be burnt from everywhere, those of rock must be destroyed, and it must be done a report to His Excelence the General about the returning of the churches (to the united) and also about the action of demolishing the monasteries, and if someone would remonstrate against the supreme royal order, he shall be punished by all means, with death by scaffold or by cutting his head off, just like some who despise the royal order and abash the public peace and order”(Ilarion Puscariu, Documente pentru istorie si limba, vol.I, Sibiu, 1898, p.233). The distruction of the hermitages and monasteries was not a campaign action, but an action that lasted the whole 18th century, retrospected to the capped heads who have underwritten the action, from Carol the V th – the father, MariaTereza- the daughter and Iosif the II nd – the nephew: “A family business”. The moment Maria Tereza – Nicolae Adolf von Buccow, consumed during two years (1767-1762), was strongly imprinted in the collective memory and the general was equalised with an evil symbol. 11 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… The first hurtful episode for the monachism from Transilvania took place in the first half of the 18th century, founded on the changes produced by: the establishment of the habsburgic domination, the transformation of the Orthodox Church from Transilvania into annex of the Catholic Church (1696-1700), the war of rioters (1703-1711), the rebellion of Visarion Serai and the opposition more and more evident of the orthodoxes towards the union. Several historians and cultivated men were preoccupied with the destructions caused then with a fury that worried some of the officials and some men of the Church – except for the bishop Petru Pavel Aron- and this is the reson for which they inventorized and often reconstructed in their works, the history of the destroyed monasteries. Anyhow, those who in the name of the power’s right have subjugated the Church from Transilvania to all hardships, from humility to the distruction of the halidoms, they couldn’t understand that the sacred cannot be destroyed, that it is forever. In the sacred places of the churches, of hermitages and of monasteries, people met with God, they got close to Him through words. The word connects people with each other, and people with something. This fact was unknown to the ones who destroyed the monasteries: that the establishment can disappear in a way or another, but the pledges remain. This is why all the monasteries remained quiet, without power to move, in the collective memory, by means of the word, the names of the places, hills, valleys, woods, meadows, even the ones who destroyed them were forced to admit their existence the moment they drew up maps, landed books, cadastres or such registered works regarding the boundaries. Although physically lost the hermitages and the monasteries have been spiritually ‘rebuilt’ in the hearts and the consciousness of the believers, who confered eternity upon the sainted places, putting them in the patrimony of the oral history as goods of the national thesaurus. The places where the hermitages have been, became so sacred as the halidom that adorned them once. Over the mounds of ashes and ruins left after the monasteries’ arson ans collapse were built crosses and those places have been marked in order to always remember that there was a place of meeting with God. The romanian Orthodox monasteries from Maramureş and Northern Transilvania besides their fate of religious hearth and monasterial inwardness, they have been at the same time romanian institutions for defense and custody of the national conscience and national unity of the Romanians living on both sides of the Carpathians. 12 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… The humble origin of the religious education are interlaced with the humble origin of the romanian education in general. The education was practiced only by the church for a long period of our past, because of its needs to form men-servants. Even the children of hospodars or of noblemen learnt near some priests or scholar monks, in the church’s entry, at the monasterial, episcopalian and vicarage schools. It is certainly not the case here to talk about the foundation of some systematic schools, but about their incipient stage. Thus, monasteries are the first culture centers from which appeared, in time the light of science near the chairs of the eparchy and near the churches from the towns and from some villages too, and the monks can be considered the first founders of the romanian school. Gradually, near the monasteries, especially near the ones which were substantialy more gifted have started to function ‘cell schools’ or in ‘church entry’ for the prepartion of the priests, deacons, schoolmasters, clerks, and not only, in this way becoming centers of irradiation of culture. Such monasterial schools have been in: Bârsana, Budeşti, Căşiel, Ciceu - Poieni, Chiueşti, Ciocmani, Cutiş, Dolheni, Feldru, Ieud, Leurda, Moisei, Negileşti, Peri, Rebra, Strâmba - Fizeşului, Valea Căşeielului, Vălenii Şomcutei, Sângeorz - Băi, Şimişna, Vad, Zagra. In the 16th –17th century, education has registered a favourable evolution, as a consequence of the fact that the necessity of assuaring the access to education was understood, moreover this access was without any ethnical, confessional or social discrimination. After a period of assertion of the monasterial schools, in the 18th century, especially in the second half, following the leopoldine and iosephine reforms, their place will be occupied by the rural schools. As the monastic orders and the orthodox monachism have been abolished, the monasteries remain just places for education. In monasteries a special significance and importance was given to the manuscripts- copies and printed books, these being printed in monasterial presses. The religious and church authonomy of Maramureş had certain consequences over the spiritual and cultural life of its inhabitants: many monasteries were built, certain books were translated into romanian, books that are considered to be the origin of the romanian writing. The manuscripts found there in full process of rhotacism were identified as belonging to the men-servants from the romanian orthodox hermitages from Maramureş. Near the monastery from Peri, was periodically functioning a press, which printed not only books written in Slavonic, but also two books in Romanian (Evanghelie, 13 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… Molitvelnic) and others in Slavonic (Bucvar, Penticostarion, Triod) and Ukranian (Penticostar). The center of the artistical activity were the monasteries, where the technical traditions of old times have becalmed. In a period, in which architectonic preoccupations seemed unimportant, the monasteries, by means of their founders, had them, for building solid and imposing edifices which they adorned with immortal and art treasures. The north-transilvanian religious art has a very long and rich tradition. The relatively great number of : icons from the 15th and 17th century and churches of wood from 16th – 18th century prove the existence of a remarkable local art activity and represent the proof of a high handicraft skill, who knew how to combine the resistence with the armony of the shapes, constructing lasting churches with elegant forms, creating in fact a style, the Maramureş’s style. Even from the 16th century, but especially on the following centuries in the lands of the Northern Transilvania took shape -on the two Someş rivers, Maramureş, Sălajauthentical and valuable ‘painting schools’ illustrated by the big number of the painters and of the works they realized: icons, rood screens, painted churches. Monachism’s role in the progressive formation of the romanian spirituality is undeniable. The romanian monks have been near the people, they have been opened to the people’s spiritual and cultural needs. People received an education by sermons or by the religious service and church paintings, but also by procuring and spreading the books, the monasteries being real depositary of books. We will probably never know how many books were brought from Moldova and Ţara Românească, who brought them and what material efforts the buyers did for giving them to the churches or monasteries. From the book downry of the monasteries – lost or put in museums and collections – we know only few tenths. The romanian monasteries accomplished a double mission along the time, in peace and humility: they permanently watched at the spiritual salvation of the people, but they opened their minds too, by teaching them to love the traditional earth, the orthodox faith and the romanaian language, custom which existed in monasteries until nowadays and it has always been the support of the historical permanence of the Romanians. In this context, we must underline the fact that monks and monasteries had a great contribution in the conservation of the language and the romanian notion’s unity, which was for a long time separated in three countries because of the vicissitudes of the time. But, 14 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… the exchange of monks, the movements of manuscripts or of books among these countries never stopped. Among Transilvania, Ţara Românească and Moldova existed strong and lasting links concerning both the national and religious idea. The noblemen and the hospodars from Moldova and Muntenia did donations for maintaining monachism in Transilvania, and thus it was the donation of a calyx by Brâncoveanu Vodă for the monastery The White Church and a discos given by Toma Cantacuzino to the monastery from Şomcuta Mare, objects which are preserved even today at the History Museum from Baia Mare and at the Orthodox Parish from Şomcuta Mare. These links among the Romanians from both sides of the Carpathians, who compose an extremely important and favourable chapter for the history of the romanian nation explain the traffic of the ideas , the unity and the faith’s depth in Romanians, the unity and the beauty of our customs. What other significance could have the circulation of the romanian old books of cult and their presence in the villages from Maramureş, Sătmar, Lăpuş, Chioar, or the Valley of the Someş river, short after their printing. Many monks received their education at the Athos Mountain or in the Romanian Countries, then they ordained themselves and came back in Transilvania for giving spiritual help to the orthodoxes from here. Many of them brought to Transilvania jewels, books for services, writings about the Holy Parents, lay and religious manuscripts for the education of the believers. The Romanians from Maramureş had an important part in the foundation of the moldavian state. A century later, Moldova will pay its debts towards Maramureş by irradiating here the force of his civilization. The essential contribution which Moldova brought to Transilvania is linked to the committal of crystallization of a church institution, under the circumstances in which the orthodox Romanians did not have a structured frame in whose limits to manifest their membership. In the 18th century many young from the Valley of Someş river or Bistriţa river or from Maramureş went to the monasteries from Moldova to learn; some of them came back as priests to advice the people from their villages, others remained there and became hegumens of monasteries and bishops, moreover even metropolitans. In Moldova they were sanctified for being bishops of Maramureş and the Northern parts of Ardeal: Iosif Stoica (1690), Ioan Ţirca (1706), Dosoftei Teodorovici (1718). The bishop Pahomie (18th century) was from Gledin (tha county of Bistriţa Năsăud) and he entered the monastery in 1697, at the monastery Neamţ. 15 Monahismul ortodox din Maramureş şi Transilvania Septentrională… The romanian nation’s cultural history must be searched for in our church history. Our church history is a history of culture too. Christianity meant for us not only spiritual salvation, but also culture and civilization. Once with the destruction of the hermitages and of the monasteries –as walls but also as monastic life- almost all the cultural vestiges were destroyed: the archives with the documents, books, manuscripts, icons - a real history, that is everything that could have remained as a testimony and talk to the next ganerations about the beginning of Christianity, of orthodox monachism and the social and cultural missionary activity in this part of the country and about the custody of the national human being. The great majority of the monks, a little if at all known, modest inhabitants of the hermitages, seldom mentioned in statistics only as numbers, had an important role in the custody and defense of faith imposing themselves in the history of romanian monachism and the history of culture by means of their literary, artistic or theological creations, others by their lives of confessors. The orthodox monasteries from Transilvania have always answered to the spiritual necessities of the romanian nation even if Transilvania couldn’t enjoy the blooming of a monastic life similar to the one from Ţara Românească or Moldova. 16