What`s in a word

advertisement

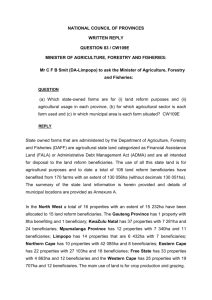

What's in a word Author : Jennifer Pfuetzner Date : May 2010 ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jennifer Pfuetzner TEP is an Associate Lawyer at Taylor McCaffrey LLP T he natural meaning of the word ‘issue’ is descendants of all degrees, meaning one’s children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren etc. Interpretation problems can arise when it appears in the will that this term was intended to mean only the first generation of descendants, or ‘children.’ The word ‘issue’ will only be given the secondary meaning of ‘children’ if that meaning was intended by the testator, based on clear and cogent evidence from the rest of the will.1 Therefore, my recommendation is to only use ‘issue’ in a will in the context of its primary natural meaning of descendants of all degrees. How to use per stirpes One of the most frequent problems I see in wills prepared by lawyers is the misuse of the term per stirpes. The only proper way to use per stirpes is with the word ‘issue’, as in the following phrase: ‘among my issue in equal shares per stirpes.’ Any other use of the term per stirpes is not legally correct and will potentially create a serious interpretation problem. Per stirpes describes the manner in which property is to be divided among beneficiaries, but does not identify or define those beneficiaries. It is a division literally by ‘the stocks.’ In a division among ‘issue per stirpes’, the division into shares takes place at the first generation, where there is a living individual. The living individuals of that generation are each entitled to one share. If there are any individuals of that generation who have predeceased, the share that he or she would have received will be divided in the same manner among his or her descendants. So a division among issue per stirpes will exclude some surviving issue, in the case where there is one or more interceding ancestors between the surviving individual and the testator. The key point to remember is that per stirpes does not identify or add beneficiaries. It merely describes the manner of division among the class of beneficiaries, that class being the ‘issue’ of the testator or another person. Examples of Canadian Cases that have analysed use of per stirpes In Re Clark Estate2 the court considered the phrase ‘children per stirpes.’ The court decided that there was no intention to provide for a gift over to surviving issue of any children who predeceased. The court speculated that the solicitor and client did not fully understand the meaning of ‘per stirpes’ and had merely left it in the will based on its appearance in a precedent. The court essentially refused to give a meaning to the phrase ‘children per stirpes’ that would have resulted in expanding the class of beneficiaries beyond children. The recent Ontario case of Lau v Mak3 considered the effect of a will that left property ‘equally between Jackie and Shirley, as his or her own property absolutely, in equal shares per stirpes.’ Shirley predeceased. The question posed to the court was whether the addition of the words per stirpes after the gift to Shirley had the effect of enlarging the class of beneficiaries in the will to include Shirley’s descendants. After carefully reviewing the Canadian authorities, Justice Cullity determined that the words per stirpes had no meaning in the context in which it was used in this will. It is so important that we as lawyers use this phrase correctly, as it is clear that many judges are reluctant to expand the meaning or use of per stirpes beyond its traditional technical meaning and are willing to recognise that some solicitors do not really understand the meaning of the phrase. Per capita It is important to understand the difference between a division ‘per stirpes’ and a division ‘per capita.’ A division per capita provides one equal share to each and every living member of the class of beneficiaries. A division ‘among issue in equal shares per capita’ would provide an equal share to each living child, grandchild and great-grandchild of the testator, regardless of how many living interceding ancestors there are between the individual and the testator. Therefore, you must be extremely careful as to how you combine the phrases per capita and per stirpes with the beneficiary classes of ‘children’ and ‘issue.’ Gifting shares of residue When drafting a residuary clause, lawyers should carefully consider how to ensure that the entire residue is disposed of and that a partial intestacy will be avoided, even if one of the named residuary beneficiaries has predeceased. Problems that I have seen in residuary clauses include: giving away percentages of the residue, the total sum of which add up to more, or less, than 100 per cent giving a share or percentage of the residue to a beneficiary and not providing for an alternative gift in the event that the named beneficiary predeceased. I have seen more than one estate being administered and distributed on the mistaken belief that such a gift automatically gets added back into the residue and divided among the surviving residuary beneficiaries – it does not – it belongs to the intestate successors of the testator. These were cases where anti-lapse provisions in modern legislation did not apply. Better ways to deal with residuary clauses include: never use percentages; use equal shares as they don’t have to add up to 100; include a general clause in the will providing that the share of a residuary beneficiary that has predeceased will be divided equally or pro rata (as the case may be) among the surviving residuary beneficiaries, or use a preamble to the allocation of shares of residue that says ‘divide the residue of my estate into as many equal shares as shall be required to make the following distributions…’ and then set out the list of beneficiaries entitled to shares, each one with the condition ‘provided he survives me.’ Therefore only the shares of the surviving beneficiaries will be set aside when the division of residue is made, as the other shares are not required under the preamble. Problems with will trusts Trusts in wills sometimes seem to be added as an afterthought, or precedents are used and amended without due care. Common errors include: Trust of residue for a deceased beneficiary. This is a trust of residue that is conditional on the life tenant surviving the testator. The will entirely fails to dispose of the residue in the event that the life tenant predeceases. What happens? An application to court for advice and directions would be made to determine if the residue goes on an intestacy. ‘Am I forgetting something?’ Trusts – these are the trusts that forget to dispose of the income or capital of the trust fund. Another example is a discretionary trust that fails to contain a direction to accumulate unpaid income. Remainder interests in trusts that vest on the death of the testator. The first example is a trust that provides for payment of income ‘to my spouse for life with the remainder to my children who survive me’ (as opposed to my children who survive the survivor of me and my spouse). The children have vested interests in the remainder on the testator’s death. If a child dies during the lifetime of the spouse, the child’s interest has already vested and goes to the child’s estate to be dealt with under his or her will, or to be distributed to his or her intestate successors or creditors. The second example is a trust for a young person where distribution is delayed until past the age of majority, but there is no gift over if the person dies before that age. Setting aside the potential application of the common law rule in Saunders v Vautier, the trust has fully vested in the young person and, if he or she dies, the fund would be distributed as part of his or her estate. The following two topics deal with issues arising when drafting mirror wills for spouses. Double dipping legatees When spouses give instructions for mirror wills, they sometimes instruct that, (i) upon the death of the first spouse, the residue goes to the survivor (ii) upon the death of the survivor of them, certain legacies should be paid, and (iii) the residue is then to be distributed to the ultimate beneficiaries. Typically, one drafts each of the mirror wills to provide as follows: To pay the residue to my spouse if he survives me by fifteen days; If my spouse fails to survive me by fifteen days, to pay the following legacies: CAD10,000 to Joe and CAD15,000 to Sam; If my spouse fails to survive me by fifteen days, to divide the residue as follows… However, what happens if the spouses die within less than fifteen days of each other, leaving the mirror wills? The legacies that appear in the wills will be paid twice – once out of each estate. There are ways to draft around this problem. For example, the condition precedent for payment of the legacies could be drafted differently under each will. So one will should continue to say ‘if my spouse fails to survive me by fifteen days to pay…’. However, the other will should say ‘if I survive my spouse by fifteen days to pay…’. In that manner, the legacies will only be paid out under the first will if the spouses died within less than fifteen days of each other. The beneficiary lottery This refers to the phenomenon of spouses (usually those without joint children) who instruct you to draft wills where everything goes to the surviving spouse, but if there is no surviving spouse, they each want their estate to go to their own list of beneficiaries. For example, the wife’s will provides: ‘to my husband, and if he fails to survive me by fifteen days, to my nieces and nephews who survive me, in equal shares’. The husband’s will provides: ‘to my wife, and if she fails to survive me by fifteen days, to the following three charities…’ The potential inequity here would occur if one spouse died and the survivor died 16 days later, having inherited all the first spouse’s assets. The second spouse’s beneficiaries would receive the entire joint estate and the first spouse’s beneficiaries would receive nothing. When I raise this possibility with clients, most of them view it as too random an outcome. I recommend drafting both wills so that the ultimate beneficiaries are identical. For example, under each will, the residue could be split half to the wife’s beneficiaries and half to the husband’s. I hope this article will be a useful guide to identifying and avoiding common will drafting pitfalls. 1. Adams v Laursen 1998 CarswellBC 1211, 23 E.T.R. (2d) 317 (B.C.S.C.). 2. 1993 CarswellBC 253, 83 B.C.L.R. (2d) 284, 50 E.T.R. 105, [1994] 1W.W.R. 497. 3. 2004 CanLII 6673, 10 E.T.R. (3d) 152 (Ont. S.C.).