SPEECH TO THE HERALD

advertisement

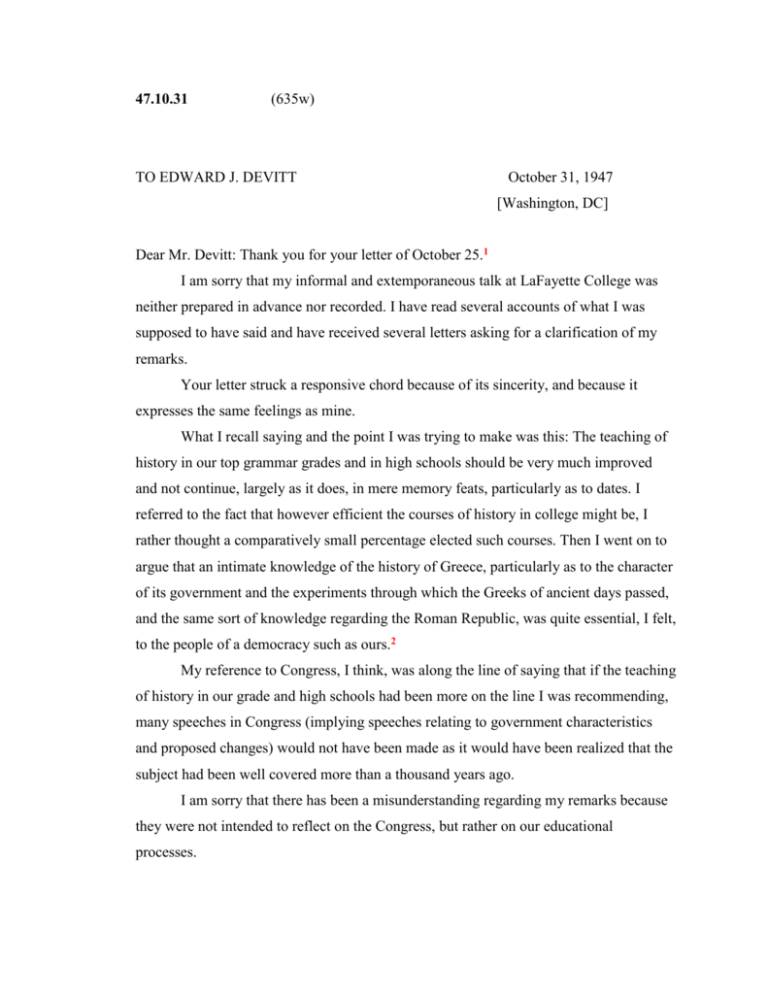

47.10.31 (635w) TO EDWARD J. DEVITT October 31, 1947 [Washington, DC] Dear Mr. Devitt: Thank you for your letter of October 25.1 I am sorry that my informal and extemporaneous talk at LaFayette College was neither prepared in advance nor recorded. I have read several accounts of what I was supposed to have said and have received several letters asking for a clarification of my remarks. Your letter struck a responsive chord because of its sincerity, and because it expresses the same feelings as mine. What I recall saying and the point I was trying to make was this: The teaching of history in our top grammar grades and in high schools should be very much improved and not continue, largely as it does, in mere memory feats, particularly as to dates. I referred to the fact that however efficient the courses of history in college might be, I rather thought a comparatively small percentage elected such courses. Then I went on to argue that an intimate knowledge of the history of Greece, particularly as to the character of its government and the experiments through which the Greeks of ancient days passed, and the same sort of knowledge regarding the Roman Republic, was quite essential, I felt, to the people of a democracy such as ours.2 My reference to Congress, I think, was along the line of saying that if the teaching of history in our grade and high schools had been more on the line I was recommending, many speeches in Congress (implying speeches relating to government characteristics and proposed changes) would not have been made as it would have been realized that the subject had been well covered more than a thousand years ago. I am sorry that there has been a misunderstanding regarding my remarks because they were not intended to reflect on the Congress, but rather on our educational processes. 2 The fact of the matter is that I had been assured that I would not be called on to make any remarks and after receiving a Degree and being seated, I was introduced with the request that some remarks from me would be greatly appreciated. Under the circumstances, rather than appear utterly innocuous, I turned my attention to the subject of the teaching of history, about which I have long felt very strongly. The press reached in and, without regard to the context, made the comments which you have read. I imagine you have had the same experience yourself a good many times. Faithfully yours, GCMRL/G. C. Marshall Papers (Secretary of State, General) 2 3 1. A first-term Republican from Minnesota, Devitt was a member of the House Committee on the Judiciary. He wrote to Marshall on October 25 commenting on a brief mention of Marshall’s remarks at Lafayette College’s Founders Day (October 18) in the current issue of Time magazine that cited Marshall as saying that members of Congress ought to know something about history. If they could be familiarized with the past, “about three-fourths of the speeches would be eliminated. . . . They would know these speeches had already been said.” (Time, October 27, 1947, p. 50.) Devitt defended his colleagues as mainly “well educated, hardworking, intelligent persons of above average capacity. They have studied history.” The congressman was “personally grieved” by Marshall’s criticism. (Devitt to Marshall October 25, 1947, GCMRL/G. C. Marshall Papers [Secretary of State, General].) 2. Marshall had long been critical of teachers and textbooks that emphasized rote memorization of facts and dates alone, as well as excessively inflating the quality of traditional American military prowess and preparedness—to the soldiers’ and country’s detriment in the early days of war. See his speeches to the Headmasters Association, February 10, 1923 (Papers of GCM, 1: 219–22), the American Historical Association, December 28, 1939 (ibid., 2: 124–25), and Princeton University, February 22, 1947, p. 000 . 3