THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION AND THE COUNTER

advertisement

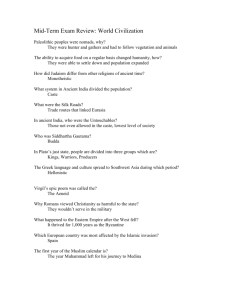

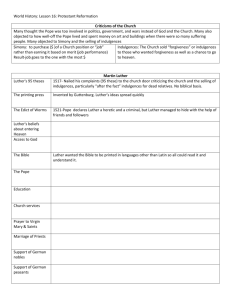

THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION Historical Background—the Renaissance Popes Early 15th century Italy—explosion of creative and intellectual activity, rediscovery of learning, science, art, and values of ancient Greece and Rome—the Renaissance. Martin V (1413-1431) and his successor Eugenius IV (1431-1447) reasserted papal authority after the Great Western Schism. The next pope, Nicholas V (1447-1455), the first of the Renaissance popes, set about restoring Rome, repairing the ancient monuments. Nicholas and his successors focused their efforts on beautifying Rome through Renaissance art and architecture but did not reform the Church. These Renaissance popes were known for their lavish lifestyles and worldly indulgences. To their credit, these popes used large sums of money to build St. Peter’s Square, the Sistine Chapel, and other Vatican sites. Julius II (1503-1513) began a huge campaign of funding the money to build St. Peter’s Square by selling indulgences. Leo X (1513-1521) who was the son of a Medici ruler of Florence spent time in hunting, and ceremonies, ignored the business of reforming the Church. He also promoted the sale of indulgences. Historical Background—Europe at the Time of Reformation Early 16th century—the Age of Exploration had begun, and missionaries were sent to the new world to evangelize new peoples Local parishes had been suffering neglect, and indifference from the papacy. Many of the clergy were untrained and uneducated and did not meet the needs of many Christians. The Renaissance period was an age of rising literacy, so people expected more out of life. The Church resorted to the sale of indulgences to pay for its expenses. This was not a new concept; some of the money or the army raised to fight in the Crusades was from indulgences. An indulgence was a way to buy divine favor in the afterlife; that is, indulgences may be purchased to “lessen an individual’s, or a deceased loved one’s, time spent in purgatory.” Many reformists cried for reform within the Church. Some reform did come but were very few. Besides the spiritual unrest that was being felt in Europe, many monarchs desired to control their national churches and church lands. In 1516, the French monarchy was so strong that Pope Leo X had to compromise by making French King Francis I the independent head of the Church in France. In Spain, the Spanish were successful in defeating the Moors after centuries of Muslim rule. The marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile (the Catholic Monarchs) formed a strong monarchy that “governed” the Church. This same monarchy launched the Spanish Inquisition that resulted in thousands of suspected heretics being imprisoned, tortured, or even killed. In Germany, the Hapsburg Holy Roman Empire remained firmly Catholic though anti-papal sentiment increased. Poland, Holland, Bohemia, and Hungary were eager 1 to free themselves of papal authority. Particularly in Holland, the people struggled to free itself from the Catholic Church and Spanish rule. The fires of religious and political resentment against papal corruption and authority burned brightest in Germany, Switzerland, France, and England. Here in these countries can be found the reformers of the Church that radically changed Christianity to this day. In 1517, the printing press was able to produce mass copies in print. This new technology was a key factor in the rapid spread of the reformation. MARTIN LUTHER’S TEACHINGS Luther was a vocal critic of the sale of indulgences. When he discovered a secret arrangement between a Dominican Johann Tetzel and Prince Albert of Brandenburg that allowed Albert to obtain the office of archbishop through bribery, and using an illicit loan from indulgence money, Luther made it public information. His “Ninety-five Theses” questioned also papal authority to forgive sins, the ‘true treasure’ of the Church (which he believed was the gospel message of salvation) and papal infallibility. He developed the theology of Sola Scriptura (‘scripture alone,’ that is, the Bible alone is the final authority for Christians) and Sola Fide (‘faith alone,’ that is, salvation comes by faith alone and not by good works). He believed that the Bible should be available to all people, and that every Christian is a member of the priesthood of believers. Luther condemned church traditions about the sacraments, the saints, and anything not explicitly found in the Bible. WHAT HAPPENED NEXT Many radical changes were coming after Luther’s posting of his Ninety-five Theses. Luther’s actions caused polarization among the powers in Germany. Many Germans were sympathetic to Luther. Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire reluctantly outlawed Luther’s teachings as heresy at the bequest of Pope Leo X. Meanwhile, Prince Frederick of Saxony sided with Luther. Luther was excommunicated by Leo X and later ordered to be burned as a heretic. That didn’t happen because Luther was given protection by Prince Frederick. Many of Luther’s followers were also peasants. A Peasants’ Revolt in the 1520’s was initially supported by Luther but later condemned it after they burned castles and churches. Then, Luther flip-flopped by allowing German princes license to use “whatever means necessary” to put down the revolt. The result was a massacre of 10,000 peasants by the German princes. At this, Luther flip-flopped again and condemned the massacre, but lost the support of the peasants. Lutheranism polarized Germany to where certain German princes either sided with Catholicism or Protestantism. War soon broke out. In 1555, a peace treaty, the Treaty of Augsburg, allowed each prince to make his territory either Lutheran or Catholic. Lutheranism spread to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Bohemian Hussites initiated reform in Poland. Lutherans elsewhere in Europe united against Catholic authority. 2 Other Protestants like Ulrich Zwingli of Switzerland, and John Calvin of France founded the Reformed Churches and spread other heresies in Europe. Other Protestant reformation churches founded as a result of Luther: the Dutch Reformed Church, Huguenots in Switzerland, Scottish Presbyterianism, the Anabaptists (later became the Amish and Mennonite Churches) and the Anglican Church of England. Source: Price, Matthew, and Collins, Michael. The Story of Christianity: 2000 Years of Faith. Dorling Kindersley Publishers.1999. 3