DBQsample -- Ottoman

advertisement

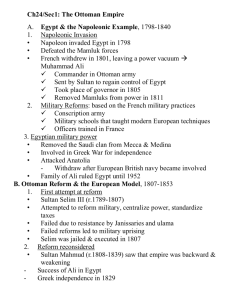

DBQ: For the period 1876-1908, analyze how the Ottoman government viewed ethnic and religious groups within its empire. What additional kind of document(s) would help analyze the views of the Ottoman Empire? [Refer to handouts: Documents One through Seven] From its founding in 1453 with the conquest of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire emerged as a world power that would have to balance its Islamic and Turkish roots with the diversity of its subject peoples1. Within a century, the empire reached its apex with the reign of Suleyman in the mid-1500s. But from that point forward the empire struggled to stave off its slow decline and ultimate demise, which came in the aftermath of The Great War in 19182. The documents at hand exemplify the ethnic and religious tensions that existed within the empire as it struggled with reform, and they illustrate why the Ottomans inevitably were incapable of maintaining their empire in an age of rising nationalism3. The documents reveal that the Ottoman government attempted to make concessions to its manifold ethnic and religious groups, but in the end it still viewed non-Muslims and non-Turks as second-class citizens4. The nationalities table (Doc. 1), the comments of Suleyman Husnu Pasha (Doc. 5) and the memo from historian Ahmed Cevdet Pasha (Doc. 6) point out the challenge faced by the Ottoman government: Ottoman Turks constituted less than 50 percent of the empire, while no fewer than 20 subgroups – each with a distinct cultural heritage – made up the remainder of the empire’s population of 28.5 million people5. Thus, the ruling class found itself in the minority, faced with the dilemma of how to peacefully maintain This is an introductory sentence that’s designed to show I know a bit about the history of the Ottoman Empire (I’m bringing in some background knowledge, which isn’t required but could help me in the expanded core) and immediately establishes one of the issues in question from the documents – diversity within the empire. 1 2 These last two sentences put the timeframe of 1876-1908 into broader historical context, and again reveal some background knowledge on my part. As I initially wrote this, I thought I was crafting my thesis … but as I edited myself (I do this continually), and checked to see if I was explicitly addressing the particulars of the DBQ question, I realized that I needed more. Hence, the next sentence. 3 Here’s the thesis statement. Whether by itself or in tandem with the previous sentence, it nails the thesis point on the Scoring Guide because it is an argument that can now be defended, and it accounts for Ottoman views of ethnic and religious groups. Had I to do it over again, I would compress the last two sentences of the first paragraph into this stronger, more concise thesis: The documents at hand reveal that the Ottoman government attempted to make concessions to its manifold ethnic and religious groups, but in the end it still viewed non-Muslims and non-Turks as second-class citizens – a stance that inevitably prevented it from maintaining its empire in an age of rising nationalism. 4 Here I’ve made my first grouping of documents (1,5 and 6), all of which show – in one way or another – the striking diversity of the empire. [Notice that I’ve referred to the documents in at least two ways: what each one is and/or to whom it’s attributed, as well as the document number itself.] Implicit in this point about diversity is the dilemma of a ruling class that finds itself in the minority … 5 power over the multiethnic majority6. In an attempt to keep this cauldron from boiling over with ethnic and religious strife, Tanzimat reformers in the decades prior to 1876 drew inspiration from European traditions, moving somewhat away from Ottoman law and pushing for reforms such as guaranteed public trials and equality under the law for all citizens, Muslim or not7. The resulting 1876 constitution enshrined liberal reforms, but the constitution’s excerpts (Doc. 2), along with Documents 5 and 6, show that Islam remained the official state religion8. The historian, in fact, identifies Islam as the unifying force bringing together the Ottoman Empire’s many peoples. It follows that a weakening of Islam and its role in the political structure of the state would consequently mean a weakening of the state itself9. Conservative critics of the liberal reforms did in fact make this case10. In any event, the declaration in Document 2, Article 11 that the state would protect the “free exercise of faiths” while still maintaining Islam as the official faith would seem to be an effort at religious duality that was bound to fail. One wonders, for example, if the article’s condition of maintaining “public order and morality” would in actual practice mean prejudicial or restrictive treatment of faiths other than Islam11. Evidence that the Ottoman government viewed ethnic and religious groups other than Muslim Turks as second-class citizens can be found both from within and without12. The historian, definitely an “insider” in that he was also a statesman, flatly states that Turks naturally should be “accorded more worth” than others (Doc. 6)13, while Davis’ lecture (Doc. 3) provides the Christian view that liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire … so I’ve connected the dots in this sentence, converting the implicit to the explicit, making it easy on the AP reader to clearly understand my thoughts. DO NOT FEAR BEING REDUNDANT; GO OUT OF YOUR WAY TO BE EXPLICIT. 6 Here is some more background knowledge – brownie points for the expanded core. It helps set the stage contextually for the 1876 constitution, but a DBQ essay without this thrown in would still maintain its integrity. In other words, if this sentence weren’t here, the essay would still be just fine. 7 This is an important sentence in that it echoes the central focus of my thesis. I’ve grouped the documents again in a new way (2, 5 and 6), and the but is critical: The reforms were liberal but not entirely so. 8 This I’ve pulled from my own analytical mind. This is the essence of what the AP readers want to see – you working with documents and making some kind of sense of them. 9 10 More background knowledge … more brownie points for me! These last two sentences again show that I’m analyzing and interpreting a document just like a historian would. This is one of the skills the AP wants you to develop by taking this course. Also note, here and elsewhere, that I’m making sparing use of direct quotes. AP readers want to see you paraphrasing for the most part, so that they’re confident you really understand the documents (understanding the basic meaning of all [or all but one of] the documents is a point for you in the Basic Core scoring). 11 I’m explicitly saying, “Hey, reader, I’m about to give you some specific evidence in support of my thesis. It’s going to come from Ottomans and non-Ottomans, Turks and non-Turks. Here it comes. Get ready. It’s going to be as clear as day. Really.” 12 13 Note the multiple ways of referring to the documentary evidence (to make it easy on the AP reader) and the use of only a brief direct quote. have not changed the fact that Turks have been a huge thorn in the side of Christians. Davis’ viewpoint no doubt carries the baggage of a Brit’s take on the Crusades and their legacies, so perhaps his assertion that the Turks are a “ceaseless cause of misery” does not give adequate due to the Ottoman reforms of the Tanzimat era, and in any event his lecture predates the constitutional reforms by more than a month14. Along with Doc. 3, the excerpt from the Armenian baker’s book (Doc. 4)15 further details an outsider’s view. One must almost read between the lines or infer the author’s intent with his observations of the sultan’s different sets of guards. There is a hierarchy to the inner and outer rings of guards, with the innermost being exclusively Turkish, all tall and displaying decorations16. That these acute observations of the sultan’s guards come from an Armenian is surely no coincidence, given the Ottoman massacre of Armenians in the late 1890s (and again in 1915)17. In the end, the liberal reforms in evidence by the 1876 constitution (Doc. 2) and the later Young Turks movement (Doc. 7)18 offered considerable rights to all Ottomans. But the underlying tensions that gave rise to separatist movements eventually proved fatal to the Ottoman Empire, as it was unable to reconcile its own diversity along ethnic and religious lines19. Further proof of this thesis – that the patina of legal protections to nonTurks and non-Muslims were inadequate to more fundamental cultural disagreements among Ottoman constituents – could likely be found in, for example, a diary of one of the empire’s Greeks or Serbs. It would be interesting to see the level of nationalistic fervor of a typical Ottoman Greek or Serb, given that Greece itself gained independence in 1830 and Serbia did so in 1867. Such Ottoman ethnic minorities would likely harbor strengthening feelings of nationalism, something the Ottoman government would be forced to recognize and deal with while simultaneously maintaining the preeminence of According to the Scoring Guide, I must analyze the point of view of at least two documents. Here I’ve zeroed in on the source line for Document 3, inferring that an Owen Davis speaking at a British Congregational Church is neither Muslim nor Turk. He would likely have views biased in a certain way, and I’m not thrown off by the irony of his lecture’s title, “Those Dear Turks.” 14 15 Count this as one more grouping … I’m good for another point on the asset-based Scoring Guide. 16 These last two sentences reveal analysis and, I believe, correct interpretation of the document … … and here I’m providing analysis informed by background knowledge. A persecuted ethnic group is the ultimate outsider’s view, which is the point of my grouping. I’m also accounting for another POV. 17 Another grouping and, now with the inclusion of Document 7, I’ve accounted for all of the DBQ’s seven documents. Score another point. 18 These first two sentences of what is the last paragraph of the essay essentially restate my thesis. It’s always a good idea to do this in the final paragraph because AP readers will give you credit for having an acceptable thesis if they find it in the first or last paragraph. You might think you’ve stated the thesis in the opening paragraph – but the AP reader might feel differently. By restating your thesis here at the end in a slightly different way, after you’ve written the body of the essay and come to more clearly understand what you’re trying to say exactly, you’re doubling your chances of earning a point for having an acceptable thesis. 19 Muslim and Turk20. What is more, the most critical document one would need to assess the views of the Ottoman Empire would be from Sultan Abdulhamid II himself. He ruled autocratically, pursuing Tanzimat reforms for decades. He suspended the 1876 constitution, dissolved parliament and either exiled or executed those who challenged him. His views – expressed perhaps in a letter to another government official, or recorded for posterity by an aid – would literally be the view of the government insofar as he was the government21. 20 These three sentences identify one additional kind of document that would aid my analysis. They not only suggest a document, they explain what it would likely show and why it would be useful – showing off some additional historical background in the process. And these final four sentences provide the rationale for a second additional document. I’ve once again brought in some background knowledge, and I’ve gone beyond the requirements of the Basic Core. As I look back through the essay, I think I’ve satisfied all 7 points of the Basic Core and believe additional points on the Expanded Core are warranted. I’m now in a great position to move on the change-over-time essay and the comparative essay. 21