Read the rest of the interview by clicking here.

advertisement

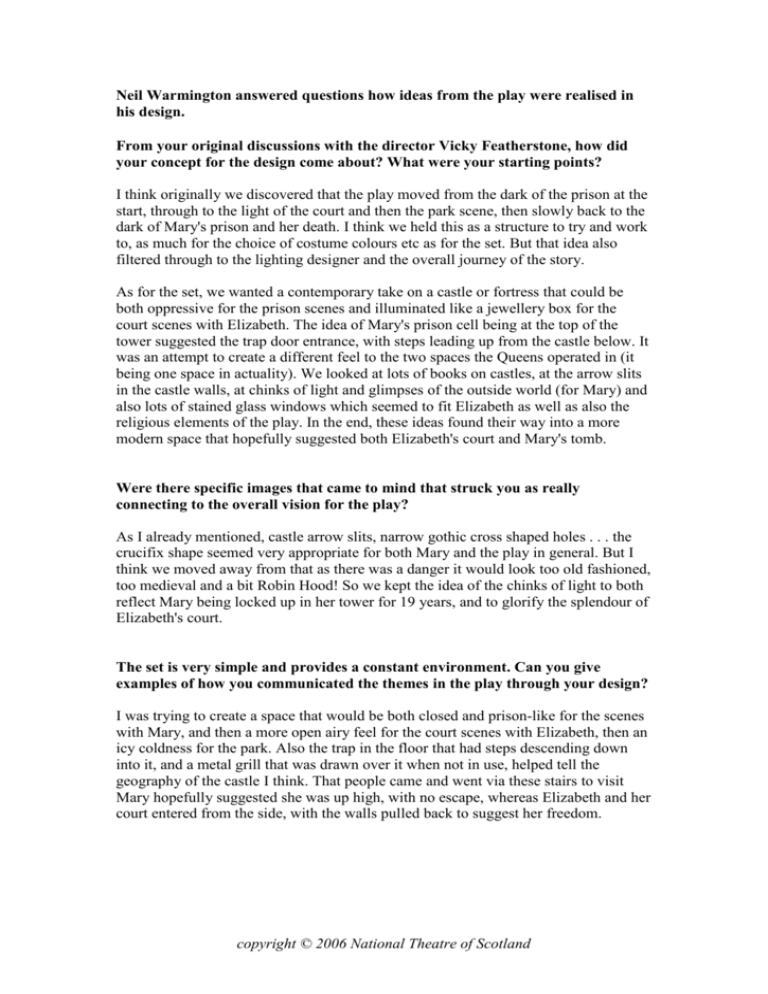

Neil Warmington answered questions how ideas from the play were realised in his design. From your original discussions with the director Vicky Featherstone, how did your concept for the design come about? What were your starting points? I think originally we discovered that the play moved from the dark of the prison at the start, through to the light of the court and then the park scene, then slowly back to the dark of Mary's prison and her death. I think we held this as a structure to try and work to, as much for the choice of costume colours etc as for the set. But that idea also filtered through to the lighting designer and the overall journey of the story. As for the set, we wanted a contemporary take on a castle or fortress that could be both oppressive for the prison scenes and illuminated like a jewellery box for the court scenes with Elizabeth. The idea of Mary's prison cell being at the top of the tower suggested the trap door entrance, with steps leading up from the castle below. It was an attempt to create a different feel to the two spaces the Queens operated in (it being one space in actuality). We looked at lots of books on castles, at the arrow slits in the castle walls, at chinks of light and glimpses of the outside world (for Mary) and also lots of stained glass windows which seemed to fit Elizabeth as well as also the religious elements of the play. In the end, these ideas found their way into a more modern space that hopefully suggested both Elizabeth's court and Mary's tomb. Were there specific images that came to mind that struck you as really connecting to the overall vision for the play? As I already mentioned, castle arrow slits, narrow gothic cross shaped holes . . . the crucifix shape seemed very appropriate for both Mary and the play in general. But I think we moved away from that as there was a danger it would look too old fashioned, too medieval and a bit Robin Hood! So we kept the idea of the chinks of light to both reflect Mary being locked up in her tower for 19 years, and to glorify the splendour of Elizabeth's court. The set is very simple and provides a constant environment. Can you give examples of how you communicated the themes in the play through your design? I was trying to create a space that would be both closed and prison-like for the scenes with Mary, and then a more open airy feel for the court scenes with Elizabeth, then an icy coldness for the park. Also the trap in the floor that had steps descending down into it, and a metal grill that was drawn over it when not in use, helped tell the geography of the castle I think. That people came and went via these stairs to visit Mary hopefully suggested she was up high, with no escape, whereas Elizabeth and her court entered from the side, with the walls pulled back to suggest her freedom. copyright © 2006 National Theatre of Scotland What did you do in terms of research? Did you discover any gems, any new ideas or potentials that you hadn't considered before? I spent many hours in Borders looking at books on castles and Scottish history and pictures of Mary and Elizabeth for costume ideas. Plus I used the internet a fair bit, which has some great costume reference sites that weren't available a few years ago. I spent a day trawling the streets of Glasgow looking at the different surfaces of buildings: the marble of banks, or inside the City Chambers just to get a feel for how marble was put together: slab, veneer, or polished. Apart from that, there was the technical side of working to the plans of the theatre stage, and making the proportions fit both the space and number of actors and different requirements of the play. The production staff at the Citizens Theatre worked very hard gathering different samples of marble, from lino to plastics. We ended up having the whole lot scanned by a computer onto projection screen as this gave the best finish and also allowed the lighting designer to make the back wall change appearance and solidity for the park scene. Something she wouldn't have been able to achieve if we had made it from something solid like lino. Could you comment on the creative collaboration of all the designers? Can you identify a moment in the play where you feel all the production elements come together in a powerful way? I think a designer's role is very collaborative. At least for me it is. I think you'd be silly not to listen to all the various departments like wardrobe and carpenters and stage management and actors, who are all specialists in their field, with many years of collective experience. For example, in wardrobe there are cutters who draw out the patterns for the costumes from your designs, and they are highly skilled in their own right. It makes sense to listen to them when they say things like, 'Could we do it this way instead as I think it would be better?', or, 'I think a heavier fabric would suit this dress.' In a way, a designer's job is to keep hold of the bigger picture, of what colours are on stage at the same time, or whether the colours slowly change, etc. If you allow people to advise and contribute, it not only makes for a more enjoyable time, but also a better end result as they bring details and expertise that you have only skimmed the surface of. I think of my job as being responsible for everything on stage, from a pen to a certain glass, chair, or costume. Then the lighting brings something more, plus the sound designer will bring another layer. I think theatre is at its best when you are not aware of any one element but of the whole. I think Mary Stuart achieved that very well. Lighting, set, sound and direction were all pulling in the same direction. copyright © 2006 National Theatre of Scotland Would you be able to briefly describe your ideas for the costumes? Were they clear in your mind before rehearsals or was there input from the actors also? I think we knew that it would be interesting to put Elizabeth in period costume so that she stood apart. It is such a beautiful image, that farthingale skirt and her ruff and tinkerbell wings, that it would be a shame not to use it to portray her power. I think if we'd updated her to more modern dress it would have diluted her status a lot. I think the men in suits seemed a nice play on the court. It was a very political play, of people meeting in corridors, of watching their backs. The modern Royal family – court life, parliament, MPs – seemed a very logical reference point for all the debate and jostling for position that went on. I also think it made it more real. Women's costume in Elizabethan times was truly beautiful; men's costume was baggy shorts and tights and funny slippers. I think to a modern day audience that image of a man with a stuffed codpiece and tights would have been quite distracting for what were very serious scenes debating the history of England and Scotland's future. What were the particular challenges that this play presented and how did you overcome them? I think every play is a challenge. I can't quite believe I come up with ideas at all. Often you can't remember how you did it after it's all over. Theatre is so collaborative that it's not really who comes up with the idea that is important, more that the idea has come up at all. The challenges were it touring to the Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh after its run at the Citizen's Theatre in Glasgow. To make the set work technically in both spaces involves a lot of planning that isn't needed if the play is only being performed at one theatre. Things like the position of the trapdoor were determined by both theatres’ facilities. Luckily the positions for the having a hole in the floor were fairly close, but you still need to overlay plans and do a lot of maths to make sure it fits in both spaces. The fact that it is a co-production means you have to treat both spaces as equally important. It has to look as good in both venues, otherwise it stops being an equal partnership. Neil Warmington was talking to Naomi Ludlam. copyright © 2006 National Theatre of Scotland