Московский государственный институт международных

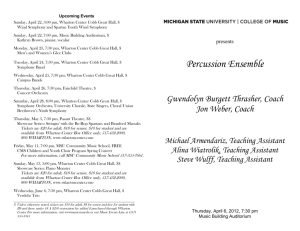

advertisement