Inventories - NYU Stern School of Business

advertisement

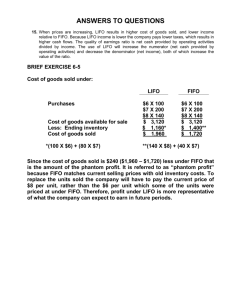

Professor Paul Zarowin - NYU Stern School of Business Financial Reporting and Analysis - B10.2302/C10.0021 - Class Notes Inventories I/S (CGS): LIFO vs FIFO B/S (inventory): FISH vs LISH LIFO Reserve Δ LIFO Reserve: compare LIFO vs FIFO CGS Δ LIFO Reserve: price effect and quantity effect quantity effect = ΔQ (RC - HC); dip profits, realized holding gains LIFO layers LIFO liquidations and earnings management LIFO inventory management price effect = Qb * (RCe - RCb) LIFO disclosures LIFO tax savings switch from FIFO to LIFO Dollar Value LIFO Inventories Everyone should know the basic LIFO, FIFO, and Average Cost inventory methods. In this module, we will discuss: (1) LIFO reserve disclosures, (3) Dollar Value LIFO, and (4) lower of cost or market (LCM). LIFO Liquidations (dipping into inventory layers) In a year in which a LIFO firm purchases (or produces) more units than it sells, it builds up a LIFO layer (a group of units at a give year=s purchase price). Thus, a LIFO firm=s EI is composed of numerous layers, and the per unit cost of most layers is lower than the current (FIFO) cost. Thus, if a LIFO firm sells more units than it purchases, it must take items from BI. This is Adipping into LIFO layers@. It is important, because putting the older, lower cost items into CGS reduces CGS (relative to maintaining or increasing inventory levels), raising NI and taxes (this is the Aquantity effect@, see below). To avoid this, LIFO firms may Amanage@ their inventories to avoid dips (for example, by accelerating purchases at year-end), and this might not be best for the firm=s operations (i.e., the firm might maintain higher than optimal inventory levels). For example, a LIFO firm that faces a potential dipping situation near the end of the year might accelerate purchasing or production (causing a higher per unit cost than necessary) in order to avoid the dip, because dipping would result in a higher tax bill. [The penalty here is that the IRS=s LIFO conformity rule says that if firms use LIFO to get the tax benefits of higher CGS (lower NI and lower tax payments), they must use LIFO for financial reporting.] Alternatively, if the firm is having a bad year, management might want to dip, in order to show higher NI. Thus, the managerial incentives can work either way. FIFO firms do not manage their inventories in this way, because accelerated year-end purchases do not affect CGS. Note that while a LIFO firm can calculate the FIFO (replacement cost) value of its inventories, a FIFO firm can=t calculate the LIFO value of its inventories. This is because the FIFO firm must know about the component layers, but it would not have such information. This is why a switch to LIFO is not a cumulative effect or retroactive change, because the dollar magnitude of the switch cannot be calculated. LIFO Reserve Disclosures The names FIFO and LIFO focus on the I/S, i.e., what costs go into CGS. A more useful way to think of FIFO and LIFO is from a B/S perspective: FIFO=LISH (last in, still here); LIFO=FISH (first in still here). Since prices generally rise over time, LISH valuation is greater than FISH. Because of the discrepancy between FISH and current cost, firms that use LIFO must report in a footnote the difference between the B/S (LIFO) valuation of their inventories versus the current or replacement valuation of these inventories, at both the beginning and the end of the year. This difference is called the LIFO reserve. Intuitively, the LIFO reserve equals the number of units in inventory times the difference between their current cost and their (historical) LIFO cost. Thus, a large LIFO reserve results from a large number of inventory units and/or a big difference between their historical vs current cost. Reporting this difference is important because the LIFO valuation can be an old, out-of-date number. Since, LIFO means FISH, the LIFO balance on the B/S may be very different from current market valuation. Note that this out of date valuation is not a problem with FIFO (LISH), because the FIFO inventory balance is like a current valuation. That is why some firms report the LIFO reserve as the difference between the LIFO balance and what the inventory balance on the B/S would be if the firm used FIFO (called Aas if FIFO@). Thus, adding the LIFO reserve to the LIFO B/S number tells you the FIFO or current (replacement) cost value of the inventory. In addition to converting the inventory on the B/S to FIFO valuation, the LIFO reserve can be used to convert the LIFO CGS to an Aas if FIFO@ CGS. This is done by using the inventory identity: ΔBI + ΔPUR = ΔEI + ΔCGS, where Δ is the difference between the LIFO and FIFO values: ΔBI is the LIFO reserve at the beginning of the year, and ΔEI is the LIFO reserve at the end of the year. Let ΔPUR = 0 (this means that purchasing behavior is not affected by choice of inventory method), and solve for ΔCGS; i.e., the change in the LIFO reserve (from the beginning to the end of the year), equals the difference between the LIFO and (Aas if @) FIFO CGS. Thus, it is important to understand why the LIFO reserves changes from the beginning to the end of the year. Intuitively, changes in either the number of inventory units and/or their replacement cost change the LIFO reserve. The attached page decomposes the change in the LIFO reserve into 1. a price effect (the change in replacement costs times the beginning quantity), and 2. a quantity effect (the change in the number of units times the difference between the current and historical costs). This decomposition helps us to understand how the LIFO reserve changes. The beginning quantity and the the difference between the current and historical costs must be positive; but the change in replacement cost and the change in quantity can be either positive or negative. The most interesting (and counter intuitive) case is when the LIFO reserve declines, i.e., when LIFO CGS < FIFO CGS. From the decomposition, we can see that this happens when quantity falls (a dip) and/or replacement costs fall (a deflation year). The effect of a dip on NI must be disclosed, if this effect is material (this is the quantity effect, component 2 in the previous paragraph). The disclosure is required, because the dip=s enhancing effect on NI is transitory (the firm cannot dip forever, because quantity is not infinite). Since LIFO inventory is in layers, it is easy to know if a LIFO firm dipped (besides the footnote disclosure): a decline in the B/S amount of inventory implies a dip. By contrast, the B/S cannot tell whether a FIFO firm increased or decreased inventories. Recall that FIFO inventories are like current cost (LISH). Thus, an increase or decrease in the inventory balance can be due to either a change in physical quantities or a change in quantities. The LIFO reserve can also tell you the firm=s cumulative benefits from LIFO (relative to FIFO), since the firm first adopted LIFO. The benefit of LIFO is the tax savings from higher CGS (lower NI), which is why firms use LIFO in the first place, despite the LIFO conformity rule. How much is this benefit? From the inventory identity, all costs of inventory (the left side of the equation) must go into EI or CGS. As noted in the previous paragraph, ΔEI is the LIFO reserve at the end of the year. From the identity, ΔEI equals minus ΔCGS (because GAS is given). Thus, ΔCGS is the cumulative CGS difference since the firm first adopted LIFO. The cumulative tax savings equals ΔCGS x the marginal tax rate. In fact, this calculation is an underestimate of the tax savings benefit, because it ignores the reinvestment of the cash. Dollar Value LIFO - DVL DVL is based on layers and uses a specific price index for each layer. The DVL balance on the B/S is the sum, over all layers, of the quantity in each layer x the price index of the layer. This is probably the way you learned to think about LIFO in intro accounting, with one inventory layer and one price (the end of year price index, rather than an actual purchase price) per year. The importance of DVL is that since real goods flow is (almost always) FIFO, companies know the FIFO value of their inventories, i.e., the current quantity at the current year price. But a LIFO company must report LIFO value on the B/S. DVL is a practical way to translate FIFO (current) value into LIFO value. The steps to do DVL are: 1. Start with beginning and ending inventory at their current prices 2. Restate beginning and ending inventory to base year price, by dividing by their price indices you must choose a base year 3. Using EI and BI at base year price (i.e., holding prices constant), compute change in inventory 4. Restate this quantity change into current prices, by multiplying by the current price index 5. DVL ending inventory balance = DVL beginning inventory balance + the change from 4. 6. For dipping, peel off layers at the price they were added Another way to think about DVL is to start with base year inventory at base year price, and to add layers at their current year prices. Lower of Cost or Market (LCM) The key issue with LCM is choosing the M. There are 3 choices: 1. Replacement Cost (RC) 2. Net Realizable Value (NRV) = estimated selling price - normal disposal costs 3. NRV - normal profit margin Obviously #2 > #3. #2 and #3 are the ceiling and floor, above and below which M cannot go. In effect, M = RC, except (1) if RC > ceiling, use the ceiling, (2) if RC < floor, use the floor. In practice, this means using the middle value of 1, 2, and 3 for M. Then compare Market to Cost, and use the lower one. Note that LCM can be applied to either individual goods or to groups of inventory. Differences in application will affect both the B/S amount of inventory and recognition of any write-downs.