Fear and (Self) Loathing in Lubbock, Texas

advertisement

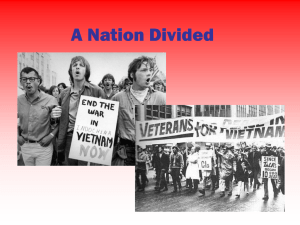

Fear and (Self) Loathing in Lubbock, Texas, or How I Learned to Quit Worrying and Love Vietnam and Iraq The U.S. lost the Vietnam War because “the American people came to hate the war” and, hence, “they hated themselves.” Normally, one might think that such an observation would come from a talk-show host or new age guru, but those words were uttered not by Dr. Phil of TV fame, but Dr. Keith Taylor of Cornell University, one of our more esteemed historians of Vietnam studies.1 Dr. Taylor’s belief (I’m reluctant to call it an analysis) reflects an increasing trend in studies of the Vietnam War–namely the rehabilitation of southern Vietnam2 and its leaders, a renewed justification of the American war on Vietnam, and increasingly stronger alibis for the failure to defeat the Vietnamese communists and retain a state below the seventeenth parallel. Taylor’s expressed his views recently at the 5th Triennial Symposium on the Vietnam War sponsored by the Vietnam Center at Texas Tech. That Taylor would offer his views at Texas Tech is not surprising, but it is a cause for concern that such ideas have become the de facto party line at the Vietnam Center in Lubbock and increasingly popular in public discussions of Vietnam. Unlike the Vietnam archives there, which remain a valuable resource with well-trained and professional archivists for anyone studying the war, the Center clearly resembles a right-wing think tank. On the surface, its ideological underpinnings are not a problem–institutions should be able to reflect a variety of opinions–but the Center also seeks academic legitimacy and claims to represent, as its director James Reckner says, opinions all along the spectrum of views on Vietnam. While it is true that Reckner has given a voice to officials from the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and some antiwar groups, such as the Vietnam Veterans Against the War [VVAW], the vast majority of voices heard at Center events tend to represent the far right to the near right. Since it was established by a number of Vietnam Vets and has included a number of influential retired officers and government officials on its board, this might not be surprising, and is not illegitimate. But it seems to be imperative that the representatives of the Center in Lubbock make clear what their mission and purpose is. In the past decade or so, the Center has featured, among others, Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, William Colby, Sam Johnson, a right-wing congressman from Texas, General Vang Pao, Laotian commander and alleged drug lord in Southeast Asia, many officials from the government and army of southern Vietnam, a number of representatives from POW-MIA groups (in fact, with Bruce Franklin’s discrediting of the POW-MIA issue, Texas Tech seems to be the last refuge for people in that particular cottage industry), Stephen Young (who argued that everyone who protested against the war in Vietnam should be brought up on charges of treason), the Swift Boat Veterans, and a host of scholars defending the war and castigating those who opposed it.3 Indeed, at the conferences I have attended, well-established and respected scholars like George Herring, Randall Woods, and David Anderson seem to have constituted the left fringe of the proceedings, probably a unique experience for any of them. But the issue is also bigger than what goes on in Lubbock. Over the past few years there has been a revival of Vietnam revisionism. While the war was undeniably unpopular while it was being fought, it was politically and intellectually rebuilt in the early 1980s, when candidate Ronald Reagan called it a “noble cause” and Army Colonel Harry Summers published the best-selling On Strategy to defend the war and give impetus to the “stabbed in the back” thesis that has become de rigeur among many conservatives. Just in the past half-decade or so, scholars like Michael Lind, Lewis Sorley, Ed Miller, Mark Moyar, Ron Frankum, BG Burkett and Glenna Whitley, and of course Keith Taylor, among others, have written and delivered papers arguing, on many points, that the war was indeed a noble cause, that Vietnam below the seventeenth parallel was a viable and stable state, that the war was not fought disproportionately by the poor, that the U.S. military won in the field but was undermined at home, and that poor decisions and leadership in the United States–not the skills and appeal of the Vietnamese communists–were the main reason for American failure. Today, with the United States facing uncertain, if not dismal, prospects in the aftermath of its invasion of Iraq, such messages are not only poor history but bad politics, for they are being used to justify more than the war in Indochina in the 1960s and 1970s but American foreign policy and intervention sui generis. Refighting the Last War In the decade or so after the Vietnam War ended, most scholars wrote critically of the U.S. intervention in Indochina. George Herring’s America’s Longest War (1979, 4th edition 2001) was the first serious scholarly entry in the field and remains a standard today. While not an overtly harsh indictment of the American intervention, it certainly presents the decision to fight in Vietnam and subsequent involvement and escalation as clear mistakes. More pointedly, George McT. Kahin’s Intervention (1986) and Gabriel Kolko’s Anatomy of a War (1985) were early and powerful denunciations of the war, from two scholars who were also active in the antiwar movement and familiar with many of the Vietnamese leaders on a personal basis. Since that time, most scholarly books on Vietnam have tended to be critical of U.S. policy on many levels. Recently, however, there has been a drift away from those approaches–normally a good sign in historiography but one that also holds peril. In the early 1990s, historians began to reappraise John F. Kennedy’s role in Vietnam, and began to argue that the young president, had he not been felled by an assassin’s bullet, would have withdrawn American troops from Indochina, or at least not escalated the conflict into a major war. Not only old Kennedy standbys like Arthur Schlesinger but also Robert Dallek, Howard Jones, Fred Logevall, David Kaiser, Lawrence Freedman, and others have made this claim. No mind that Kennedy’s death should have logically closed this issue, there is now a fairly significant public belief, especially promoted by the Oliver Stone movie on JFK, that Kennedy was a dove on Vietnam and Lyndon Johnson was responsible for the eventual tragedy.4 More recently, the revival of the war has gone further, with Philip Catton, Ed Miller, and others claiming that America’s hand-picked leader in southern Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, was actually a capable leader and his ouster and death, sanctioned by the U.S., was a major mistake in retrospect for he was developing a stable regime below the seventeenth parallel. Indeed, at a session, chaired by Keith Taylor, during the 2004 meeting of the Society of Historians of American Foreign Relations [SHAFR], Ron Frankum and Mark Moyar spoke glowingly of Diem, with only a few concerned questions from the audience of experts.5 At the same time, BG Burkett and Glenna Whitley, Lewis Sorley, and Michael Lind, among others, put out forceful justifications of the war and revised interpretations of the men who led and fought it. American soldiers suffered from “stolen valor” and had their “history” and their “heroes” robbed from them by the media, politicians and activists who opposed the war. Lind and Sorley moreover contend that the United States actually won the war militarily, but lost due to weak politicians who were unwilling to defend southern Vietnam against the northern onslaught from 1973-1975, and that the intervention in fact was essential to the containment of communism in the Cold War.6 The Race is to the Swift . . . Boats: the 2004 Election and Vietnam Despite these recent efforts to rewrite the war positively, most recent work on Vietnam continues to be critical. It would be a mistake, perhaps a grave error, however, to write off the previous authors as a fringe element. In fact, the positions they have taken received powerful reinforcement in the public sphere during the 2004 campaign, when for the first time a veteran of the Vietnam conflict, Massachusetts Senator, 3-time Purple Heart winner, and Navy Lieutenant John Kerry, was the nominee of a major party for president. Kerry, trying to compensate for public perceptions that the Democratic Party was weak on issues of war and terrorism, highlighted his Vietnam service, traveling with a “band of brothers” who had served with him on a Swift Boat in the Mekong Delta and turning his nominating convention into a military parade, complete with tales of heroism from “the ‘Nam,” supportive officers on the dais, and a symbolic salute and “reporting for duty” introduction. What Kerry left out, as is often the case, was more important than what he included. In 1971, as a representative of VVAW , Kerry spoke eloquently and harshly about the war before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and then threw away military medals–later revealed to be those of another soldier, a World War II veteran–at an antiwar protest at the Capitol. At the time, Kerry’s compelling remarks were applauded and they represented the views of a significant number–probably a majority–of Americans. Yet in 2003-2004, nary a mention was made of his role in VVAW or opposition to the war in Vietnam, and Kerry–to show his gravitas as a military man–had voted to authorize war in Iraq and to increase funding for hostilities there, and vowed to “win” in Iraq if he became commander-in-chief. If Kerry had hoped to use his experience in Vietnam as a campaign asset, he was in for a huge surprise. A Texas Republican and wealthy developer, Bob Perry, became the principal funder of the “Swift Boat Veterans for Truth,” a group of anti-Kerry veterans who charged that the senator had lied to receive two of his purple hearts and a decoration for bravery and had been disloyal and anti-American in his 1971 testimony to the senate. No matter that Navy records and Kerry’s former crew mates disproved the allegations and his views in 1971 reflected the mainstream, even within the military,7 the media took the Swift Boat story and ran with it, and Kerry did little to respond for nearly a month in August and September 2004. Nearly thirty years after the war ended in victory by the National Liberation Front and Democratic Republic of Vietnam in April 1975, Vietnam was once again a compelling national political issue. Kerry had hoped to use his story of Vietnam to take him to the White House, but the Swift Boat vets created an alternative version of both Kerry’s service and the war. The battle over a war in Indochina that had been so painful and costly decades ago was once again joined. Keith Taylor’s Vietnam: Emotions without Evidence8 Amid the backdrop of the election and power of the Swift Boat attack on Kerry–ironically in defense of an administration headed by two draft-dodgers themselves–the new rehabilitations of Vietnam take on an urgency and importance that should be recognized. If a war that was so unpopular and tragic while it was being fought can be presented so positively and affect a presidential campaign in a subsequent generation, then there are historical forces at work that need to be recognized and reckoned with. And that’s where Keith Taylor comes in. Taylor is not the most important historian of the Vietnam War nor even recognized as a leading scholar of the war period– his specialty is in Vietnam’s early history, before the tenth century–but his views are presented strongly, well-received by those who are already defensive about the war, and cumulatively representative of a much larger body of scholars and public figures–from Texas Tech to the Swift Boats–who are spoiling for a fight, or a re-fight, over Vietnam. Accordingly, it is essential to look at the type of arguments Taylor is making and to repudiate them forcefully and quickly.9 As these new versions of Vietnam are presented, and more importantly taught in high school and university classes, then future foreign invasions, such as Iraq, are facilitated. If Vietnam is indeed seen as a “noble cause,” then American forces can more easily and aggressively intervene elsewhere–in Iraq already, and perhaps Iran, North Korea, or Venezuela in the future. What is immediately striking about Taylor’s critique is its passion and anger. He’s mad at Kennedy and Johnson for their apparently half-hearted efforts to win in Indochina, upset at those who did not have his “sense of honor” and dodged the draft, disturbed by those in America who did not support the war, even if it was “ . . . a consequence of poor leadership.” But listen or read more and that anger does not dissipate–which by itself is not a problem, and I personally think we could use more passionate scholars debating vital issues–but neither, however, is it supplemented by evidence. Taylor’s arguments, like those of many other revisionists, is based on emotions, on what they feel should have happened, on their sympathy or pity for soldiers or the southern Vietnamese, or their detestation of hippies, or disrespect for political leaders who did not wage war vigorously enough, or contempt for scholars who now write disparagingly about the war–hence Taylor’s analysis about self-loathing Americans as the cause of failure in Vietnam. While I’m not an expert in psychology, neither Dr. Freud nor Dr. Phil, I do know that it is quite a leap to say that virtually an entire nation, an entire generation, hated America and hated themselves. In fact, the vast majority of those who opposed the war did so within the American tradition, and many of the most radical showed their respect for our society and our customs by refusing draft induction and accepting the consequences of it. With a few extreme examples like the Weather Underground, which had but a handful of adherents, those who protested the war did so legally and peacefully, and they included ministers, businessmen, “average Americans,” students, military officers, and a lot of soldiers. To determine that Americans came to hate their society and themselves is intellectually immature as well as an emotive outburst and an insult to those who tried to stop the war in Vietnam because of the way it was ripping apart Vietnam and American society. And yet Taylor continues. He is proud that he is “not among the self-loathing Americans who notice people in other countries looking to us for leadership and see nothing but neocolonialism and imperialism.” Just where are all these people who are looking to “us” for leadership? Apparently Taylor has not seen surveys showing vast majorities, often over 90 percent, of people in other countries holding negative views of the U.S., or is unaware of the level of hostility aimed at American institutions or symbols. Perhaps he should take a look at a document entitled “Anti-Americanism in Arab World,” which begins “anti-Americanism is resurging in the Arab world” and then lists a series of recent incidents such as bombings, “vitriolic public statements,” and “diatribes and fantastic rumors” which “all testify to the rekindling of Arab animosity against the United States.” That particular document, by the way, which could have been written in the past few months by Colin Powell or Condoleeza Rice, was produced by Dean Acheson in May 1950.10 Or perhaps he should look at, say, southern Vietnam, where so many people were apparently so eager for American leadership that they took up arms, with the Viet Minh and National Liberation Front, to attack their countrymen who collaborated with the Americans, staged a series of coups d’etat to oust American client regimes, and waged a long-term and brutal war against U.S. forces. Taken to a logical conclusion, Taylor’s opinions on Vietnam sound much like those of George Bush and others who, in the aftermath of 9/11/01 decided that the attacks in New York and Washington occurred because “they” hate “us” because “we have freedom” or because “we’re so good.” Perhaps that’s true–I doubt it, but I’ll concede it’s possible–but it would be nice to have some evidence to back it up. When considering the way the war was fought, Taylor’s emotive views again surface. One of the bigger flaws in American planning for Vietnam, we learn, was a “lack of attention.” As Taylor says, “I believe that Kennedy made bad decisions about Vietnam because he was not paying sufficient attention and Johnson did so because it was not his priority.” Hmmmm . . . Ask anyone who had done research on the Vietnam War, and he or she will tell you that one of the problems that we face is the sheer mass of documents, oral histories, interviews, and other data on the war. I doubt any conflict in history has had so many documents produced while it was being conducted. The Kennedy and Johnson Libraries have, I would suspect, many millions of pages of reports, analyses, and other information produced by virtually every agency, military branch, and diplomatic official. This massive record of the war, one would easily conclude, is testimony to the vast levels of attention given to it by national leaders and its priority in state affairs. Yet Taylor “believes” that American leaders suffered from attention-deficit disorder, that Kennedy, who saw Vietnam as a way to reclaim lost credibility lost in Laos and Cuba, and Johnson, who agonized over the war daily and went to an early grave probably due to the stress it caused him, did not take Vietnam seriously enough? Taylor’s emotions also flow freely when he tries to put Vietnam into a larger cold war context. In discussing the way he teaches Vietnam, Taylor sets up straw men and then knocks them down. First, he claims that his students today know nothing about the Cold War and think it was an effort by somewhat crazed American leaders to gain world power by threatening war against a non-existent enemy. Perhaps such a view is predominant among those who just read John Gaddis’s work for the first time, but it, again, ignores overwhelming evidence otherwise. What of the establishment of the national security state and massive military budgets, the power of the red scare after World War II, the Sputnik scare, the cultural impact of the cold war on education and entertainment, or the “bipartisanship” that takes precedence when the U.S. goes to war? In 1980 polling, 73 perecent of Americans believed that the goal of the USSR was “global domination” and 39 percent thought the Kremlin would risk “major war” to gain it; in 1985, 54 percent said Moscow posed a “real, immediate danger”; and even in 1988, after the Reagan-Gorbachev thaw, 60 percent still saw the Russians as a “serious threat” to American security due to “Soviet aggression around the world.” More recently, a February 2005 Gallup Poll showed that Americans consider Ronald Reagan the greatest president because he, they believe, “won” the Cold War.11 So, if Taylor believes that Americans are too self-critical about the Cold War, he needs to produce some evidence to back it up. In addition to his caricature of cold war critics, he tries to play the race card. At Texas Tech, Taylor claimed that opponents of the Vietnam War believed that the U.S. intervention was wrong because it was trying to modernize a people “not ready for democracy,” which, he said, was “a racist argument.” I agree. I think the Vietnamese were capable of self-determination, as demonstrated in 1945 and 1954, when Ho Chi Minh and his communist and nationalist supporters tried to develop a free and independent Vietnam, only to have the French and especially the Americans undermine them. But Taylor should look at the mirror before calling the antiwar movement racist. At the core of Taylor’s feelings about Vietnam is the idea that American leaders lost the war. By putting the onus for failure on Kennedy and Johnson’s ADHD and the antiwar movement’s self-loathing, Taylor, by deduction, takes agency away from the Vietnamese, who, one has to conclude, were not able to gain democracy on their own, but then saw the Americans mess it up as well. But that’s not racist . . .? Taylor, who believes that the U.S. was trying to help the southern Vietnamese establish democracy, seems to have a strange idea of that concept, though. He laments the notion that the “governments opposed to a non-communist Vietnam were able to mobilize their populations without regard to dissent.” Considering that only Australia, New Zealand and the Republic of Korea assisted the U.S. in Vietnam, should we assume that the nations of western Europe and Scandinavia opposed to the war were also “opposed to a non-communist Vietnam” and did not allow political dissent within their systems? But Taylor continues that line of argument, asserting that “one of the fundamental long-term aims of the United States was to develop the right to dissent” in southern Vietnam. One cannot really mock this view, because it is too repugnant to be humorous. In Guatemala, Iran, Chile, Indonesia, many nations of the Middle East, and most of Latin America the United States used its military and economic power to crush liberation movements and keep in place some of the more murderous juntas of the modern era. Are we to really believe that Castillo Armas, the Shah of Iran, Suharto, Pinochet, Middle Eastern monarchs and Israeli authorities in Palestine, Pol Pot or others supported by the U.S. were developing the right to dissent, or that the very authorities who produced McCarthyism, COINTELPRO, and “Homeland Security” were trying to extend democracy? One really expects to hear such opinions on right-wing talk radio rather or the books of John Gaddis12 rather than in the lecture halls of Cornell. And the sentiments do not stop at Vietnam. Taylor has brought his analysis up to the present, emoting about 9/11 and the current war. Ever since Vietnam, since we have hated ourselves, America has become weak. Because of that continued self-loathing, terrorists knew we were vulnerable and “9/11 happened because we were weak.” Now, with the war on Iraq foundering, Taylor is having a bad flashback of a bygone era, as the so-called Vietnam Syndrome is resurging: “I saw people at pointy-headed universities indulging as self-hating Americans” and “it seemed awfully familiar.”13 Again, emotions run into the brick wall of history. While I would deny a “Vietnam Syndrome” ever really existed–look at arms sales in the Nixon years or continued meddling in Latin America or Asia–or, if it did, that it lasted more than a few years–look at Carter’s attempt to deny the Sandinista victory in Nicaragua, his early intervention in Afghanistan, his defense budgets, and the emergence of Brzezinski–one cannot seriously look at U.S. global policies for the past two-and-a-half decades and proclaim it weak. From Reagan’s illegal wars in Latin America, bankrolled by illicit arms shipments to the outlaw government of Iran, through the attacks on Grenada, Libya, Panama and elsewhere, into the Gulf War and attendant sanctions of the 1990s, up to the present invasion of Iraq, American military power has not been quiescent. On top of that, U.S. military spending remains enormous. Indeed the current $400 billion annual pentagon budget exceeds the next 24 highest-spending countries combined.14 But, more than that, the idea that terrorists struck in September 2001 due to America’s “weakness” is, again, fundamentally anti-historical. It replaces an analysis of “our” historical role in the world, and especially in the Middle East, with affective concepts like weakness and evil. No one should try to justify al-Qaeda’s actions, but it is perilous to ignore the motives, or history, behind them. To untold numbers throughout the world, the proximate causes of 9/11–the presence of U.S. bases in Saudi Arabia, continued U.S. support of Israel’s repression of Palestine, and the destructive sanctions against the people of Iraq–rang true. To most people across the globe, 9/11 did not happen because the U.S. was “too weak” but precisely the opposite, because it is perceived to have so indiscriminately used its strength and power against weaker countries. Even if Taylor is right, and “pointyheaded” professors and activists (a category which we should assume excludes mildlyspoken professors of Vietnamese history at Cornell, apparently) are now upset because the U.S. has awakened from its weakness and is giving the world the leadership it seeks, it is folly to simply explain away Vietnam, or Iraq, as products of self-loathing and weakness rather than actually examine the basis for the enmity that so much of the world breathes upon the United States. “Facts are Stupid Things”~~Ronald Reagan Even if the defense of Vietnam put forth by Taylor and many of the Texas Tech participants is emotive and bathetic, it’s also important to recognize that emotions and symbols are powerful, and to believers they are real, not simply ethereal articles of faith. Thus it’s also important to look at the arguments put forth by Taylor and point out the way they diverge from the facts, or at least from the conclusions drawn by the large majority of scholars who have done research on the topic. Facts may be “stupid things,” as Ronald Reagan said in an alleged misstatement, but evidence does hold more legitimacy in our epistemology, at least since the Enlightenment, than do beliefs based on our values or desires. So, then, what are the specific points along our continuum of selfloathing anti-Americanism? Taylor begins by claiming that there are “three axioms in the dominant interpretation of the U.S.-Vietnam War that were established by the antiwar movement . . . and subsequently taken up at most schools and universities as the basis for explaining the war.” These axioms are, first, that there was no legitimate non-communist government in Saigon; second, that the U.S. did not have a legitimate basis for intervention in Vietnam; and, finally, that the U.S. could not have won the war under any circumstances. These points, he contends, are the “ideological debris” of the antiwar movement, not “sustainable views supported by evidence and logic.” So, Taylor now cloaks his views in the world of “evidence and logic,” but what helped him arrive at his conclusions–vast research in presidential libraries, poring over documents in the National Archives, long sojourns to study the holdings of military collections? No, “what enabled me to do this,” that is to conclude that these axioms were “debris,” was “that I finally came to terms with my own experience.” So there we have it, Taylor’s long and intimate journey– from Vietnam soldier, to veteran in grad school in Ann Arbor where he “simply subscribed to the dogmas of the antiwar slogans then fashionable,” to professor at an elite university who has seen the light about the nobility of America’s purpose in the world– becomes the basis for his “evidence and logic.” But let’s give him the benefit of the doubt, and test his axioms and other claims using the criteria of evidence and logic. Taylor claims that it’s simply a “foundational tenet of the communist version of national history” to say that Ho Chi Minh represented the only “legitimate or viable” government in Vietnam after 1945. Correlative to that, he claims that the southern government, under Ngo Dinh Diem and his successors, had established a real state. These are big statements, and he declares them with force, but what does the evidence say? We do know–if we are to believe George Herring, David Anderson, George McT. Kahin, Gabriel Kolko, Dave Marr, William Duiker and most other credible scholars who have done original research in archives and libraries–that Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh, carrying the banner of both national liberation and communism, were deeply involved in and ultimately led the resistance to French colonial rule (which, incidentally, wasn’t as bad as we make it out to be, according to Taylor) and to Japanese occupation, politically and militarily. We know that Ho advocated a strategy of inclusion, often counter to his comrades in the Indochinese Communist Party, and was willing to join with any individual or group who opposed the French.15 We know that the Viet Min carried the fight against the Japanese and against the restoration of the French colonialists in 1946, until their successful defense of Vietnamese sovereignty at Dien Bien Phu. We know that in 1945 and 1954 that Ho declared Vietnamese sovereignty–quoting from the U.S. Declaration of Independence and making overtures through the OSS and in private letters to Harry Truman for American support–but was ignored. We also know that virtually every American official who analyzed Vietnamese politics understood that Ho was overwhelmingly popular and would easily win any real election, as even President Dwight Eisenhower conceded. The Viet Minh, Army planners in Vietnam reported in 1950, enjoyed the support of 80 percent of the Vietnamese people, yet 80 percent of its followers were not Communists. That level of indigenous appeal, as well as support from China, which they conceded was limited, virtually assured Viet Minh success.16 Subsequently, the history of the war provides compelling testimony to the appeal and effectiveness of the nationalist-communist side. The NLF and Viet Cong were able to effectively challenge the Diem regime, develop broad networks of support on both sides of the seventeenth parallel, and defeat what was undoubtedly the most technologically sophisticated military ever put in the field, the U.S. armed forces in the 1960s. That, it would seem, by almost any “expert” analysis, would constitute some kind of legitimacy and viability. But it is the other side of that coin that is even more troubling, the argument that the south was a viable state. This was the gist of the panel at SHAFR consisting of Taylor, Ron Frankum and Mark Moyar, (and Philip Catton and others in print), and just as disturbing as the assertions they made–which they essentially conceded were not backed by hard evidence–was the lack of critical commentary from the audience, which was full of scholars of the Vietnam War. Perhaps academic niceties and politeness has its place, but it would certainly not have been in bad form to point out that these assertions flew in the face of what we know and have no basis behind them.17 The increasing trend to lament the “good old days” of Ngo Dinh Diem is the first piece of this revisionist puzzle. Diem, Taylor and others argue, was a real nationalist, not a puppet of the U.S., and was on the cusp of developing a sovereign state below the seventeenth parallel. Well, the Church Lady might say, isn’t that special! Again, there is a record, a vast one, of Diem’s rise and behavior and ouster. He was, as we know, a Catholic ascetic who fled Vietnam and found sanctuary in a New York seminary, where the likes of Francis Cardinal Spellman, General John O’Daniel, Mike Mansfield, and John Kennedy designated him to be the leader of southern Vietnam after 1954. In office he created a kleptocracy, with his family holding most of the important positions of state and most of the funding send to the south by the United States. Indeed, the Ngo family put 78 percent of the American aid it received between 1956 and 1960 into the budget of the military while using but 2 percent on health, housing, or welfare programs–the “stuff” of modernization.18 In fact, Wesley Fishel, an advisor from the infamous Michigan State Group and supporter of Diem, essentially admitted at the outset that Diem’s position and future were dependent on the U.S., observing that “I’ve never seen a situation like this [in southern Vietnam]. If defies imagination . . . The government is shaky as all hell. It is being propped up for the moment only with great difficulty. Nothing can help it so much as administrative, economic, and social reforms . . . The needs are enormous, the time short.”19 To solidify their power, Diem and his brother Nhu fired about 6,000 army officers and replaced them with more loyal, if less qualified, soldiers, while forcing military personnel to join the their Can Lao Party.20 The army also assumed civil police functions, and officers took over civil administration duties. Under the Ngos the civil order was steadily militarized, and the army’s responsibility was not to fight the Communists but to protect the first family. Thus secure, the Ngos went after their enemies, both real and imagined. Diem closed newspapers, made it illegal to criticize his government, and made it a capital offense to be a “communist.” By 1958, he had jailed over 40,000 political prisoners and executed over 12,000 dissidents. By 1961, those numbers had tripled. The United States apparently had little trouble with the Ngos’ behavior: Washington supplied the regime with 85 percent of its military budget and twothirds of its overall budget. Diem also set in place regressive land policies. As always, property ownership was the crucial political issue in Vietnam. In 1954, after the victory over France, the Viet Minh began to seize lands held by the French and by Vietnamese collaborators and to redistribute over 600,000 hectares of it to landless peasants. Once in power, Diem began to reverse those agrarian programs and took personal control of 650,000 hectares, much of it by denying the titles of peasants or by seizing it in place of tax payments. He then gave out about 250,000 hectares to loyal military officials and Catholic cronies, while keeping the rest, and the best, for his family. By the later 1950s, the land situation for southern peasants was not appreciably different than it had been in the French period. Diem at the same time put friends and supporters in charge of all the village councils, increased taxes, and intimidated and arrested those criticizing his land policies. In May 1959, in Law 10/59, he authorized his military-political forces to arrest any “subversives,” which was a blank check for roving bands of armed forces and Can Lao zealots to arrest, try, convict, and execute anyone suspected of disloyalty. By the early 1960s Diem’s repression had set into motion two major lines of opposition, and this is a point that the apologists always seem to ignore. Clearly, his attacks on the enemy had made an impact, and the Viet Minh in the south was in fact on the ropes, with its members often in hiding, in prison, or dead, and so the politboro in the north, due to southern pressure as much as their own designs, helped establish the National Front for the Liberation of South Viet-Nam, or the NLF. But, more importantly, Diem had alienated such vast numbers of southerners, including those ostensibly in power with him, that he had also prompted a broad internal campaign against his rule. Not only did many southerners join the NLF but his own people–army officers and government officials–began to seek ways to remove him and his family from power. The opposition political parties (suppressed by the regime) and the coups d’etat staged against him (thwarted at first) were not created by or organized by the communists, but by his own people. Finally, it was his own people –his officers, his generals–who overthrew and killed him in November 1963, with U.S. acquiescence (most likely because his brother was in talks with the NLF over a neutralist settlement, rather than any misgivings over his murder of Buddhists. Kennedy, it seems, was afraid peace might break out in Vietnam). And in the aftermath of the coup it was generals in the ARVN–not Ho Chi Minh, not the Viet Minh–who conducted an opera bouffe of government, changing heads of state as often as George Steinbrenner used to change managers, having about a dozen governments over the next 15 months. How–Keith Taylor needs to explain–does this add up to stability, legitimacy or effectiveness? How does providing the Ngo family junta with billions of dollars in aid and military equipment, as well as training, and tolerating his repression until late 1963 constitute an abandonment? How does the ouster of Diem, by his own people, constitute a grave turning point in a war that was inexorably headed toward failure from the first? If the rehabilitation of Diem is the first piece of the overall revisionist puzzle, then the argument that the southern part of Vietnam was a viable state is surely the second. As I argue in note 2 above, and James Carter has shown compellingly in a recent dissertation he completed at the University of Houston titled “Inventing Vietnam: The United States and State-Making in Southeast Asia,” there was never a real state below the seventeenth parallel, one that could exist on its own–without massive infusions of American military and economic aid, without Americans building both a political and physical infrastructure, creating a currency, covering up for the defects of its leaders, staging phony elections, dropping 4.6 million tons of bombs on an area the size of New Mexico, and so forth. “Nationhood” involves more than a titular head of state and an army–it involves consensus, sovereignty, development, international legitimacy and other defining criteria, and southern Vietnam lacked that essential “stuff” so the U.S. had to try to invent it, with results that were really not surprising to those who were involved in Vietnam decisions at the time. But don’t listen to a “pointy-headed” scholar. How about Senator Mike Mansfield, one of the senate’s experts on the area and an early supporter of Diem, who in 1965 said “We are no longer dealing with anyone [in Saigon] who represents anybody in a political sense. We are simply acting to prevent a collapse of the Vietnamese military forces which we pay for and supply.” Or Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, that same year, in the aftermath of the revolving door of governments, who said “There is no tradition of a national government in Saigon. There are no roots in the country…I don’t think we ought to take this government seriously. There is no one who can do anything. We have to do what we think we ought to regardless of what the Saigon government does.”21 In early 1965, as Johnson, who was apparently giving Vietnam some attention, deliberated over America’s future in Indochina and began to consider seriously sending combat troops to Vietnam, General William Westmoreland, cited as a hawk by many who study the war, opposed the introduction of ground forces, observing that “we would be occupying an essentially hostile foreign country.” General Victor Krulak, the Marine Corps’ Pacific Commander, was more blunt, writing to the undersecretary of the navy that “despite all our public assertions to the contrary, the South Vietnamese are not--and have never been–a nation.”22 Even more striking was the observation of a young congressman from Illinois in 1966. “Twelve years have elapsed since we began contributing economic assistance and manpower to…Vietnam, “ he said. “Yet, that nation continues to face political instability, lack a sense of nationhood, and to suffer social, religious, and regional factionalism and severe economic dislocations. Inflation continues to mount, medical care remains inadequate, land reform is virtually nonexistent, agricultural and education[al] advances are minimal, and the development of an honest, capable, and responsible civil service has hardly begun.” Thus Donald Rumsfeld laid out in some detail a strong argument against the viability of the southern state.23 Robert “Blowtorch Bob” Komer, pacification guru and hardline advocate of the American war on Vietnam, did not pull any punches either when describing the south– “Hell, with half a million men in Vietnam, we are spending twenty-one billion dollars a year, and we’re fighting the whole war with Vietnamese watching us; how can you talk about national sovereignty?” His assistant Richard Holbrooke piled on, observing that “it is still not unfair to say that there is no real government in Vietnam…It is…the result of a political structure still so fragmented and weak that division commanders can choose those orders they intend to obey, and Ministries can follow their own paths regardless of the desires of the Prime Minister.” Paul Warnke, a defense department official and longtime establishment policymaker, agreed, pointing out that “the people I talked to [in Vietnam] didn’t seem to have any feeling about South Vietnam as a country. We fought the war for a separate South Vietnam, but there wasn’t any South and there never was one.”24 Clearly, then, many of the ranking Americans who were trying to “invent” South Vietnam with billions of dollars, arms, and contracts to “Vietnam Builders” like Brown & Root did not delude themselves that they had created a real nation. In fact, it is fitting that Bui Diem, last ambassador to the fictive state of South Vietnam said, metaphorically but in fact as well, that “Americans came in like bulldozers.” More unsettling was the impact of that type of American presence–two to three million dead, a land devastated beyond any kind of quick or effective reconstruction, a social system ripped asunder, and a violent removal of people from their homelands so great that the chair of the International Rescue Committee, Leo Cherne, simply said that “it is very clear that in many respects, much of Vietnam is today a nation of refugees.”25 With the rehabilitation of Diem and legitimation of the southern state as the underpinnings of the revisionist argument, Taylor and others finish their puzzle by looking at the American side and finding that the U.S. had a legitimate basis for intervention and could have been successful had it chosen different strategies, political and military. But, again, there are stupid facts in the way. Taylor seems to argue that American intervention in Vietnam was legitimate because the U.S. has a duty “nurturing baby democracies in a world awash with tyranny.” As shown above, calling the regimes of Diem and his successors, as well as a host of client states all over the globe, “democratic” is such a bastardization of the term that it means nothing. Nor, however, does the argument have much meaning in the real world of politics. There are international conventions and institutions governing the rights of a nation to intervene in the affairs of another, the conditions under which such involvement may occur, and the rules for any conflicts arising from such interventions. On those counts, it is difficult to see any justification for the U.S. invasion of Vietnam. Even if one accepts the legitimacy and viability of the southern state, Vietnam is, at best, or worst, a civil war, and, having no sanction from the U.N. or other controlling body, America’s military invasion does not meet the test for accepted intervention.26 But the right to intervene ultimately becomes a political question, and on that count the Tayloristas have no basis either. To contend that the Kennedy and Johnson invasion of Vietnam was legitimate would seem to mean that it had a coherent basis, was done with a particular goal in mind, that its reasons were spelled out clearly, that it had been debated among the responsible parties, that it had a plan for success, politically and militarily, and, perhaps most importantly, that there was international recognition of the need for such action. But those criteria just don’t exist in the record. Only through the carrot of military contracts and other economic compensation did the United States get South Korea to join the war, and its failure to attract “many flags” to the war effort is well-established. There was no international support for the intervention. Nor was there any serious goal in mind–other than to prevent the people of Vietnam from choosing the leaders they wanted because they were almost certainly going to be communists. What is most striking when thinking about this question of the correctness of U.S. intervention is the consensus among military officials–those who would have to prosecute the war, fight, sacrifice and see their men die–that the U.S. should not intervene. In the process of writing Masters of War, based on my research in the relevant archival collections at the time, I was continually surprised, if not shocked, by the number of officers who recognized the futility of war in Vietnam, who understood the perils of warfare there, who were not enthused about fighting, and who were not optimistic about success. Far from Dr. Strangeloves dying to turn Vietnam into a “parking lot,” they were aware of the deep political problems facing any American mission in Vietnam–the popularity of the nationalist-communist forces led by Ho and the sense among the Vietnamese that the southern regimes were puppets. The officers were also aware that the nature of People’s War would make military operations in Vietnam difficult if not insurmountable, and, despite public attestations to “turning the corner” or “light at the end of the tunnel,” they were never sanguine about prospects there. Perhaps it was best explained by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who in a prescient memo in 1949, avant la chute, that “the widening political consciousness and the rise of militant nationalism among the subject people . . . cannot be reversed”; hence intervention in Vietnam would be “an anti-historical act likely in the long run to create more problems than it solves and cause more damage than benefit.”27 Blending into the Taylor argument that the war was legitimate is the belief that it was “winnable.” In this context, he blames “poor strategic thought and deficient political courage” with several barbs at the antiwar movement thrown on as topping. It is not clear what these deficiencies were, since we’re dealing with emotions rather than evidence, but it appears that Taylor believes that U.S. leaders erred, as mentioned, in not keeping Diem in power, in its strategy of attrition, in Johnson’s “decision” to “persuad[e] the enemy to give up rather than doing what was necessary to obtain victory,” LBJ’s refusal to mobilize the economy for war and call up reserves, and the president’s decision to “allow war policy to be inhibited by a misreading of the likelihood of Chinese intervention.” All of this is pretty standard stuff, promoted by Richard Nixon, William Westmoreland, Harry Summers, Guenter Lewy, Norman Podhoretz and others since the early 1980s, and all dealt with by scholars subsequently.28 I suspect it would surprise the millions of Vietnamese who lost loved ones to hear that LBJ merely decided to “persuad[e]” the enemy to give up rather than take measures “necessary to obtain victory,” whatever they might have been. Indeed, the claim that Johnson’s initial forays into Vietnam were “gradual” or “limited” ignores fundamental political and physical realities. What type and size commitment should Johnson have developed in those crucial months of 1964 and 1965? Should he have sent 500,000 men to Vietnam then? And would the congress or, more importantly, the public have supported such a massive commitment to such a small, and peripheral, country? Even during the crucial July 1965 deliberations on the war, at the end of which LBJ decided to substantially expand the U.S. force structure in Vietnam and send more troops “as needed,” the military’s biggest disagreement was over the activation of reservists, not troop numbers. And where would all these troops and arms and equipment have gone, had Johnson not pursued “limited war” and “graduated escalation?” As late as 1966, with nearly 400,000 U.S. troops in country, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara could describe Vietnam as “primarily an agricultural country; the only major port is Saigon. The deployment of large U.S. military forces, and other friendly forces such as the Korean division, in a country of this sort requires the construction of new ports, warehouse facilities, access roads, improvements to highways leading to the interior of the country and along the coasts, troop facilities, hospitals, completely new airfields and major improvements to existing airfields, communications facilities, etc.”29 Some of Taylor’s argument, such as his criticism of attrition, is on target, as almost ever critic of the war would agree.30 But much of it is just reheated right-wing dogma, used by scholars and veterans of the Vietnam era to ennoble that war, and scholars and Swift Boat veterans of this era to justify Iraq and other interventions. Obviously, the question of what “might have worked, ” is inherently antihistorical. But we can judge the war by what we do know. We know that most ranking military officials were never enthused or optimistic about the war, that they had grave misgivings about the political and military conditions they were encountering in Vietnam. We are aware of the skill and tenacity of the enemy, its ability to strike and melt back into the population, and quickly hit again. We agree that the Vietnamese enemy had an impressive capacity to withstand huge numbers of casualties, with a sturdy reserve it could call on to replenish its losses. We know that the physical infrastructure of southern Vietnam was so underdeveloped that it could not have sustained a more rapid or massive deployment of US manpower than happened. We know that the world–including traditional allies–either did not support or openly opposed the U.S. invasion. We know that the war took a huge toll at home, with over 58,000 killed and billions of dollars spent leading to a global financial crisis (a point Taylor concedes). We know that the United States unleashed the greatest concentration of firepower ever used against a small country, and, to top it all off, trained most of its destructive weaponry upon its putative ally, Vietnam below the seventeenth parallel. And we know that southern Vietnam never had a stable government, billions of American dollars and a half-million American soldiers notwithstanding. What don’t we know? Well, importantly, despite Taylor’s assertions about the “misreading” of Chinese intentions, we don’t know how the PRC would have reacted to a more aggressive war. While it may be easy to dismiss the idea that China would have come to the aid of the Vietnamese communists, memories of Korea in October 1950 were vivid and it would have been folly to attribute any certainty to any predictions about Mao Zedong’s actions amid the Cultural Revolution. We also don’t know how American soldiers–beset by problems of drugs and racial conflict and often opposed to the war themselves–would have responded if given more aggressive missions which would have caused higher casualty rates. We cannot say for certain how the rest of the world would have responded to an even more destructive American intervention in Indochina. And, maybe most importantly, we have no idea what the fallout at home would have been to more escalations of a war that never went well and was highly unpopular and costly. Just because Keith Taylor says that the war was winnable, that Kennedy and Johnson did not pay enough attention to Vietnam, that China would have sat by idly, that a more dynamic strategy, or a strategy of pacification (which is it?) would have made the difference, does not make it so. Finally, Taylor takes aim, as do the other revisionists, at the antiwar movement, antiwar politicians, and the media. Had Americans only supported the war, had not loathed themselves, the argument goes, U.S. troops would have been able to fight without restraints, without undue political considerations, with greater morale, and they would have succeeded in Vietnam. Again, this takes agency away from the Vietnamese Communists and places the outcome of the war squarely in America’s hands, but beyond that, it substitutes right-wing apologia for research and evidence. Plenty of politicians and the American people, as Taylor points out, supported the war strongly up to early 1968– the Tet Offensive. In fact, the army’s own study of media matters found that the press was not unduly adversarial or aggressive for the most part, that, “government and media first shared a common vision of American involvement in Vietnam” until the war turned sour and journalists more critical.31 In the same way, politicians were on board at the outset, as evidenced by the overwhelming votes–416-0 in the House and 88-2 in the Senate–in favor of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. And public opposition to the war, the Tayloristas refuse to recognize, was and is not a clean-cut proposition. No doubt millions of Americans from all walks of life opposed the war, but plenty supported it as well, and many held negative views of both the war and antiwar protestors. Often, if the war was perceived as going well, more people supported it; when things seemed to be going badly, the numbers in opposition rose. The Vietnamese, not the Americans, held the initiative, militarily and politically. On this point, Taylor makes special mention, as do his ideological brethren, to the events of early 1968 and the Tet Offensive, which he claims was a decisive U.S. victory in every sense yet undermined at home by weak politicians and an overly-critical media. Once more, there is evidence to indicate otherwise. Tet had laid bare claims of “light at the end of the tunnel” and showed that the enemy could attack with impunity, even inside the grounds of the U.S. embassy. It caused massive desertions among the army of southern Vietnam and caused massive setbacks to pacification programs. Westmoreland’s response, asking for 206,000 more troops and the activation of about that number of reserves, merely added to the sense of shock. Tet also highlighted the lack of international support for the U.S. war in Vietnam and exacerbated global financial problems, leading to an economic crisis that American officials feared might bring a return to 1929 conditions. In surveying the aftermath of Tet, JCS Chair Earle Wheeler admitted that “it was a very near thing” while Army Chief Harold K. Johnson lamented “we suffered a loss, there can be no doubt about it.”32 And so it goes. The withdrawal of 1973 and defeat of 1975, Taylor and Sorley and Lind argue, was another case of political officials and the American people, in effect, surrendering while on the verge of victory. Weak politicians, confused media, and self-loathing antiwar Americans dominate this ideological discourse. The Vietnamese could have had an effective government if only Ngo Dinh Diem, who was put in power by the U.S. and put untold numbers of his own people in prison or graves, had not been ousted. The “government” of southern Vietnam was stable and legitimate, never mind that it was so internally riven that it changed heads of states and regimes on a regular basis and had to be maintained by American treasure and blood. Attention-deficit suffering U.S. leaders also deserve fault, for not fighting to win, although no one seems to know what that means, nor can they logically describe that, since it did not happen. Memory and History “The struggle of man against power,” the Czech playwright Milan Kundera wrote, “is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” And so, thirty years after the liberation or fall of Saigon, we are still struggling to determine what we should remember about Vietnam, and whether it has any “lessons” to teach us today. If Swift Boat partisans and selfloathing explanations come to dominate the discourse over this past war, if the ideological detritus of the Texas Tech Vietnam Center gains more public and academic acceptance, then the doors are open to not only to the increased politicization of history in support of interventions and wars, but the legacies of those who both fought the war and fought against the war are stained. If the war can simply be explained away by concepts like “self-hating” or “weaknesses,” we have lost our history, our responsibility to use the past to learn from its mistakes and to help create a better world. The distance between My Lai and Abu Ghraib, as we have seen, is not as great as it might seem. If one of Taylor’s self-hating antiwar Americans were to stand up and say “all Vietnam soldiers were baby-killers and war criminals” then that person would, with justification, be summarily and harshly repudiated. Yet those who support the war can make ugly blanket statements about self-hatred and anti-Americanism among those who oppose wars in Vietnam and Iraq and pass them off as Ivy League scholarship. As for me, I’ll continue to rely on evidence, the archives, the work of George Herring, George Kahin, Gabriel Kolko and others. I can’t conclude anything but that Vietnam was a moral and political disaster, and that it is essential that we remind everyone we can of that, if only to make sure that those who would use Vietnam for other purposes, like war and interventions and human-rights abuses, do not do so without challenge. 1. Taylor is the author of The Birth of Vietnam, published in 1983 and reprinted in 1991, which has become one of the standard histories of Vietnam, up to the tenth century, in English. Taylor’s field is Vietnam studies, which is distinct from Vietnam War studies and generally focuses on Vietnam’s history before the arrival of European colonialists. 2 . As I’ve written elsewhere and will explain below, I think it is proper to describe the area of Vietnam below the seventeenth parallel, the demarcation line established by the U.S., Soviet Union, and People’s Republic of China, among others, at the 1954 Geneva Conference, as southern Vietnam rather than the Republic of Vietnam [RVN] or the Government of Vietnam [GVN]–as U.S. officials and, subsequently, scholars have. To call the area below the seventeenth parallel the RVN or GVN conveys a level of legitimacy that I believe does not exist. This is a key point in the analysis of Taylor and others–that southern Vietnam was a viable and real state. Needless to say, I and other historians of Vietnam see otherwise. On this point, see especially Gabriel Kolko’s Anatomy of a War and a dissertation recently completed under my supervision at the University of Houston by James Carter titled “Inventing Vietnam.” Carter shows with impressive evidence that the U.S. did not conceive of Vietnam as an independent state but as a project, a country to be essentially invented both politically and physically–in terms of its government, infrastructure, currency, foreign affairs and other accouterments of a modern state. 3 . Information about the Center and its past events can be accessed at http://www.vietnam.ttu.edu/vietnamcenter/index.htm. Despite the appearance of some speakers critical of the war, it is hard to look at rosters of past events and not see a decided right-wing tilt. 4 . Arthur Schlesinger’s Pulitzer-winning A Thousand Days, published in 1965, that is, before the massive escalation that went terribly wrong, deals with Vietnam rather matterof-factly, but in 1978, with the outcome known, he argues, in Robert Kennedy and His Times, that JFK was preparing a withdrawal or deescalation; see also John Newman, JFK and Vietnam; Howard Jones, Death of a Generation; Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life; Fred Logevall, Choosing War; David Kaiser, American Tragedy; Lawrence Freedman, Kennedy’s Wars. For a thorough repudiation of these Kennedy apologists, see Noam Chomsky, Rethinking Camelot, and Lawrence Bassett and Stephen Pelz, “The Failed Search for Victory: Vietnam and the Politics of War, in Thomas Paterson, ed., Kennedy's Quest For Victory, 223-52. 5 . Philip Catton, Diem’s Final Failure; Miller and Moyar papers presented at Texas Tech conferences on Vietnam; Ron Frankum and Mark Moyar papers delivered at 2004 meeting of the Society of Historians of American Foreign Relations, Austin, Texas. Unfortunately, the papers from that session have not been posted on the H-Diplo website at http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/reports/. 6 . BG Burkett and Glenna Whitley, Stolen Valor; Michael Lind, The Necessary War; Lewis Sorley, A Better War. 7 . It is indeed curious that Kerry refused to mount a strong defense of his 1971 views, since they did in fact represent widespread sentiment against the war in the public and even within the military. In the aftermath of the 1968 Tet Offensive, a significant number of soldiers and even officers turned against the war, and VVAW was one of the more important and effective antiwar groups. See, for instance, Richard Moser, The New Winter Soldiers; Andrew Hunt, The Turning; Gerald Nicosia, Home to War; Robert Buzzanco, Masters of War; on the Swift Boat allegations, see the Annenberg Center’s factcheck.org, at http://www.factcheck.org/article231.html. 8. My good friend William O. Walker III, now at the University of Toronto, has helped me develop my thoughts on this section, and I would like to thank him. Taylor, by making an emotive argument resting on this concept of self-loathing, is engaged in what International Relations/Political Psychology scholars call attribution theory. If “we” don’t like a particular group, then “they” are “disposed” to act against “our” interests, like those who opposed the war. It then becomes only a short, illogical leap of faith to identify them as self-loathing, thereby creating an adversarial “other.” Those in "our" favor, the well-meaning Diem clique or American soldiers who “wanted to win the war,” for example, fail but are well intended. It is the "situation" in which they find themselves that makes failure more likely. That situation is compounded by the self-loathing types. So the responsibility for failure never rests with America's authoritarian clients or, on some level, with US officials. The "self-loathing" paradigm has contemporary resonance as the spectrum of permissible dissent over U.S . adventurism increasingly narrows–and that is why the lines of thought opened by the Texas Tech crowd and Keith Taylor are in fact quite important, despite their small numbers thus far. The recourse to seeking charges of treason, real or metaphorical, against those who oppose Bushs's foreign policy is a way of stifling dissent in the name of the new American century. Terror is too dangerous for there to be freedom at home while it is pursued via intervention abroad. 9 . The subsequent critique of Taylor will be based on his article, “How I Began to Teach About the Vietnam War,” Michigan Quarterly Review, Fall 2004, his talk at the Texas Tech conference, “When Americans Hate Themselves: Another Way to Remember the Vietnam War,” and an article about the Taylor presentation in the Lubbock AvalancheJournal, 19 March 2005, pp. A1 and A8. 10 . Circular Airgram from Dean Acheson to Certain Diplomatic and Consular Offices, “Anti-Americanism in Arab World,” 1 May 1950, http://www.gwu.edu/%7Ensarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB78/propaganda%20003.pdf; see also Ussama Makdisi, Anti-Americanism in the Arab World: An Interpretation of a Brief History,” Journal of American History, September 2002. 11 . Alvin Richman, “Poll Trends: Changing American Attitudes Toward the Soviet Union,” The Public Opinion Quarterly, Spring 1991, 135-48; “Gallup Poll Reveals Reagan Now the People’s Choice,” http://www.editorandpublisher.com/eandp/news/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=100 0809416. 12 .See John Gaddis, Surprise, Security, and the American Experience; and We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History. Even many establishment thinkers, like David Kennedy and the late James Chace, have taken issue with Gaddis’s work, which puts the onus of the cold war singularly on the Soviet Union, apologizes for apparent American misdeeds in that era, and contends that the Americans have acted out of a desire to extend liberty and freedom globally. Listen to the Gaddis-Kennedy exchange at http://www.nytimes.com/audiopages/2004/07/25/books/20040725_GADDIS_AUDIO.ht ml, and Chace’s review of Gaddis, “Empire, Anyone?” New York Review of Books, 7 October 2004, excerpt at http://www.nybooks.com/articles/articlepreview?article_id’17454. 13 . Taylor in Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, 19 March 2005, A8. 14 . See graph at http://www.globalissues.org/images/USvsWorld2004Top25.gif. 15. See, for instance the older biography of Ho by Jean Lacoutre, or the more recent and comprehensive work of William Duiker. 16. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, 337-38; Army Plans and Operations position paper, “U.S. Position with Respect to Indochina,” 25 February 1950, Record Group 319, G-3 0981 Indochina, TS, in National Archives. Also in Masters of War, 31. 17. Lest anyone say “well, why didn’t you speak out,” I have to concede to briskly walking out of the room just moments before the entire panel ended. On more than one occasion I have spoken up–“pissed in the punch bowl” as a friend describes it–and I frankly don’t like the role of crank. There were many others who could have contributed and I didn’t see the need to do so and begin the equivalent of an intellectual pie fight. Perhaps I was craven, but I’d probably do the same. And in some way, this article is my penance for my silence in Austin. 18. David Anderson, Trapped by Success, 133. 19. Fishel in Letter to Edward Weidner, August 25 & September 4, 1954, Michigan States University Vietnam Advisory Group (MSUG) Papers, Vietnam Project Papers, Correspondence, Edward Weidner, 1954, box 628, folder 101; this and subsequent quotes were also used in James Carter’s dissertation at the University of Houston, “Inventing Vietnam.” 20. The following treatment of Diem is taken from my Vietnam and the Transformation of American Life, 56-58. 21. Mansfield quoted in Kahin, Intervention, 345. Lodge quote in Foreign Relations of United States, Vietnam, III, 1965, 193, again also in Carter, “Inventing Vietnam.” 22. Westmoreland and Krulak quotes in Masters of War, 190 and 257. 23. Rumsfeld in “An Investigation of the U.S. Economic and Military Assistance Programs in Vietnam,” 42nd Report by the Committee on Government Operations, October 12, 1966, 127. 24. Komer quoted in Lloyd Gardner, Pay Any Price, 303. Holbrooke quote in “Vietnam Trip Report: October 26 – November 18, 1966.” Warnke quoted in Christian Appy, Patriots, 279. 25. Bui Diem, In the Jaws of History, 127. Cherne in “Refugee Problems in South Vietnam and Laos,” U.S. Senate, Subcommittee on Refugees and Escapees of the Committee on the Judiciary, July, 1965, 56. 26. See especially Telford Taylor [a prosecutor at Nuremberg], Nuremberg and Vietnam: An American Tragedy, and Richard Falk, The Vietnam War and International Law. 27. JCS 1992/4, _U.S. Policy Toward Southeast Asia,_ 9 July 1949, 092 Asia to Europe, case 40, Records of the U.S. Army Staff, Record Group, National Archives. 28. Nixon, No More Vietnams; Westmoreland, A Soldier Reports; Summers, On Strategy; Lewy, America in Vietnam; Norman Podhoretz, Why We Were in Vietnam. 29. McNamara quote is Hearings before the Committee on Armed Services and the Subcommittee on Department of Defense of the Committee on Appropriations, United States Senate, 89th Congress, 2nd Session, January – February, 1966, 12. 30. Consider, for instance, the deep conflict between Westmoreland and the Marines, and his own boss, Army Chief of Staff Harold K. Johnson, who commissioned the PROVN report which criticized attrition and called for a strategy of pacification, covered in detail in Masters of War. 31. Quote is from promotional materials for William Hammond, Reporting Vietnam: Military and Media at War. 32. On this topic, see chapter 10, AThe Myth of Tet: Military Failure and the Politics of War,” in Masters of War.

![vietnam[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005329784_1-42b2e9fc4f7c73463c31fd4de82c4fa3-300x300.png)