INTRODUCTION

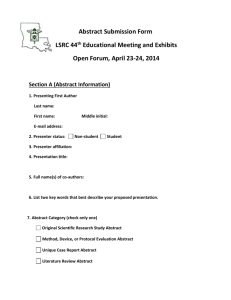

advertisement