Models of Mental Disorder

advertisement

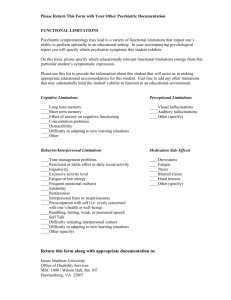

1 Models of Mental Disorder Summary Tommy Svensson and Lennart Nordenfelt (2012) Introduction Team-based psychiatric care of non-institutionalised patients requires that staff with different professional and occupational backgrounds shall be able to co-operate and make well-founded joint decisions concerning the particular patient. Furthermore it is important that patients themselves and their next of kin should to the greatest extent possible be involved in — and have a say in — the decision-making. A prerequisite for well-functioning co-operation is that the basic models of mental disorder which guide the thoughts and actions of the particular team-members shall be in accord. Such models can involve on the one hand notions concerning the essential nature of mental disorder, its aetiology and appropriate treatment, on the other hand broader notions concerning such matters as the patient’s and society’s rights and obligations in respect of care. Though in certain cases the models and the underlying notions may be explicit and well-articulated, in many cases they would seem to be simply taken for granted, implicit and perhaps not reflected upon. It is reasonable to assume that a consensus among the members of the psychiatric team with regard to the appropriate model (whether this model be articulated or not) will greatly facilitate co-operation and joint decision-making, and thereby enhance the quality of the care. In contrast, lack of consensus (especially if implicit and not reflected upon) can be supposed to give rise to difficulties and a lower quality of care. Comparatively little is known about the state of affairs in Sweden when it comes to similarities and differences between the various occupational categories making up psychiatric teams in respect of the basic models of mental disorder to which they (explicitly or implicitly) adhere. The project “Models of mental disorder and their role in joint decision-making” was designed to provide some of the missing knowledge. Background In the discussion of mental illness and mental disorder which has been so abundant since the 60s, both within the field of psychiatry and outside it, the opposition between the different paradigms, perspectives and approaches has sometimes been very much in evidence. In the early stage of this discussion there were several attempts to concretise and characterise different basic models of mental illness — models not easily reconcilable with one another. The perhaps best-known categorisation of models was drawn up by Siegler and Osmond (1974), who distinguished and described a dozen of them. Since that time, however, there has been considerably less evidence (either in Sweden or elsewhere) of open opposition between one model and another. The transformation of the organisation of psychiatric care during the so-called “de-institutionalisation period” was characterised by an increasingly marked striving for concord and co-operation both between professions and between psychiatric traditions. A now common — and perhaps somewhat idealised — representation of how severe mental 2 disorder should be understood and treated indicates that both biological, psychological and social factors are to be accorded importance (see e.g. Crafoord, Jacobsson & Åsberg 1997). It would seem often to be presupposed that that there is a sort of nuanced bio-psycho-social model to which allegiance is paid by doctors, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, mental orderlies, etc. — and perhaps, indeed, by patients and their next of kin as well. However, very little Swedish research has been undertaken concerning what allegiance is paid to this model by those engaged in the day-to-day reality of providing psychiatric care. A number of international studies indicate that a consensus model such as this can be problematised on both theoretical (Fulford 1989, 1998) and empirical (Colombo 1997) grounds. It appears that unobserved differences in the models of mental disorder to which different actors within the realm of psychiatric care at least implicitly pay allegiance can give rise to defective communication and thereby seriously impede constructive joint decisionmaking. Furnham and Bower (1992) maintain that there emerge five main paradigms when it comes to the position adopted with regard to mental illness. Colombo (1997) distinguishes a medical model, a moral one and a psychosocial one. And Taylor and Taylor (1989) say that most programmes for working with the mentally disordered in the UK are based on Colombo’s three models — or rather, on one of the three. The project “Models of mental disorder and their role in joint decision-making” was inspired by, and influenced in both conception and design by, a research project which has been going on since 1998 at the University of Warwick under the direction of Professor Bill Fulford. The starting-point for the latter project was the increasing awareness during the 90s that communication and decision-making within team-based psychiatric care were not without their problems and that certain of these problems might be attributable to divergent — sometimes, indeed, more or less irreconcilable — basic conceptions of how mental disorders should be understood and treated. The purpose of the Warwick study is on the one hand to elucidate what conceptions of the nature, causes and appropriate treatment of mental disorders are held by the different categories of staff within psychiatric care and by the patients and their next of kin, on the other hand to elucidate how the similarity or dissimilarity of these conceptions affects joint decision-making. The purpose of our project was much the same as that of the Warwick project. A further aim was that it should be possible to compare our results with the Warwick ones in certain essential respects. Purpose and principal questions addressed The purpose is twofold: first to characterise the basic models of mental disorder such as they appear among representatives of the different categories of staff making up the psychiatric team and among patients and next of kin, second to investigate whether differences between the models adhered to affect the quality of joint decision-making in psychiatric teamwork. The principal questions addressed are these: Are there essential differences between the models of mental disorder adhered to (whether explicitly or implicitly) by the different occupational groups within psychiatric teams? Are there differences with regard to such models from one clinic to another? 3 What is the relation between the staff’s models and those of patients and next of kin? Do similarities in the models make for the smooth functioning of joint decision-making in psychiatric teamwork, and dissimilarities impede it? Method and accomplishment Clinics and respondents The study concerns staff, patients and next of kin at the psychiatric clinics in the towns of Motala, Oskarshamn and Värnamo. A random stratified sample was drawn from the members of the psychiatric teams at these clinics, comprising doctors, nurses, orderlies, psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists. Motala Värnamo Oskarshamn Total Doctors 4 2 1 7 Nurses 4 4 4 12 Orderlies 4 2 4 10 Psychologists 4 4 3 11 Social workers 4 4 2 10 Occupational therapists 4 3 1 8 24 19 15 58 Total The 8 patients and 9 next of kin who participated in the study were selected by the local patient and next of kin associations. Interviews The method of data collection was semi-structured two-stage face-to-face interviews. The first stage comprised an inquiry, based on a fictitious case history, concerning basic conceptions of the causes, prognoses and appropriate treatment of severe mental disorders, whilst in the second stage the focus was on experiences of critical events in psychiatric teamwork calling for joint decision-making. Thus the interview guide was in two parts. The first focused on the respondent’s conception of the nature of mental illness/disorder — focused, in other words, on the basic model to which the respondent paid allegiance. A fictitious case history/vignette constituted 4 the basis for a number of semi-structured interview questions about conceptions of causes, consequences and treatment. The case history closely followed the case vignette used in the Warwick project but was modified so as to better fit the Swedish context. It is based on descriptions of schizophrenia to be found in DSM IV. This approach is common and welltried in research (not least that which has a social-scientific orientation) on mental-health issues (see e.g. Star 1952, Phillips 1963, Bord 1971, Howells 1984, Nieradzik & Cochrane 1985, Furnham & Rees 1988). With reference to the case history, questions were asked concerning the following topics: (1) description of the problem; (2) interpretation of the (fictitious) person’s behaviour; (3) conception of the value of diagnoses; (4) aetiological assumptions; (5) methods of treatment; (6) conception of traditional institutional psychiatric care, of non-institutional psychiatric care and of the relation between the two; (7) prognosis; (8) rights and obligations of society and of the patient. The responses to these questions were to form the basis of an analysis in terms of the different (explicit or implicit) models of mental disorder as described above. The second part of the interview involved questions concerning the experience of joint decision-making in team-based psychiatric care. The approach was that of the Critical Incident Technique. The respondents were asked to tell of any crucial clinical sequences of events where there was joint decision-making, including whether the outcome was satisfactory or not. They were encouraged to offer as exact and detailed an account as possible of what factors facilitated or impeded the decision-making and affected the outcome in a positive or negative direction. Results: Comparisons between professions The overall impression to be gained from the data is that there would seem to be a considerable degree of agreement among the representatives of the different professions as to the causes, characteristics and appropriate treatment of mental disorders. Broadly speaking, there appears to be a well-established bio-psycho-social model underlying the manner in which issues are considered and described. Only rarely, for example, did any of the respondents argue in favour of a clear-cut exclusively biological or psychological approach. Nor did it often occur that a person rejected or disparaged the angle of approach adopted by a team-member of another profession. Nevertheless there are fairly distinct differences of emphasis within the framework of the prevalent bio-psycho-social model. Most of the doctors emerge as embracing a more or less marked biomedical point of view, though at the same time acknowledging the importance of other points of view when it comes to assessing a patient’s need for care. This biomedical stance comes out most clearly in respect of on the one hand the importance assigned to diagnosis and medication, on the other a consensus of opinion that Erik, the fictitious protagonist, is ill. A more diversified picture emerges in the case of both the nurses and the mental orderlies. Some of them strongly favour a biomedical standpoint, others a more psychosocial one. There is similar variation in the view of diagnoses, which are seen by some as descriptions of symptoms but by others principally as a means of professional understanding. The psychologists are generally cautious in the use of psychiatric diagnoses, though there are those that see such a diagnosis as an equally valid alternative. Naturally enough, the psychologists are those who most clearly perceive the utility of conversation as a form of treatment — it is worthy of note, however, that few of them directly reject medication as an alternative. 5 Common to the social workers and the occupational therapists is that more often than not there was an unwillingness to offer a diagnosis of Erik simply on the basis of the case history. They wanted more information about the case and its context. Though some of them did see medication as an alternative, the general view was that other forms of treatment were called for and that the first thing to do was to determine what network the patient had. A marked characteristic of the occupational therapists is the divergent view of what should be given priority. Attention should not in the first place be directed towards the illness but towards the patient’s ability to function in daily life in spite of the illness. Thus treatment of the illness was not the primary concern. Comparison with the Warwick study The Warwick study (Colombo et al. 2003) which was briefly referred to in the Background section was the source of inspiration for — and indeed to a great extent the model for — our study with regard to design and data collection. One of our aims was that it should to some extent be possible to compare our results with those of the English study. In contrast with our study, the Warwick study started from a predefined model typology. On the basis of literature studies six models of mental disorder were set forth: a “medical” (“organic”) one, a “social” one, a “cognitive-behavioural” one, a “psychotherapeutic” one, a “family-orientated” one and a “conspiratorial” one. It was presumed that these models were clearly distinguishable from one another with regard to the conception of mental disorder (involving assumptions concerning aetiology, the significance of diagnoses, etc.), with regard to measures to be taken (treatment strategies, hospitalisation, hospital care in relation to community-based care, etc.) and with regard to ideology (conception of the rights and obligations of the patient and of society, etc.). Twenty persons from each of the following categories involved in psychiatric teamwork were interviewed: psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, social workers, patients, next of kin. As in our study, the interviews involved on the one hand questions in respect of a “case vignette” designed to identify implicit models of mental disorder, on the other hand questions concerning joint decision-making based on descriptions of “critical incidents”. The most important findings from the study are that the models receive markedly different support from the different professional groups involved and that the patient group endorse two models and can be divided into two distinct sub-groups in accordance with which of the two they endorse The pyschiatrists massively endorse the medical model whilst the social workers endorse the social model. The psychiatric nurses strongly endorse the medical model but also endorse the psychotherapeutic and social models. One sub-group of patients more or less unequivocally endorse the medical model, the other sub-group incline to the psychotherapeutic or the social model. Colombo et al. maintain in their analysis that the results point to ideological tension between psychiatrists and social workers, a portent of difficulties in co-operation. Psychiatric nurses often have to act as “mediators” between the different ways of looking at things, thereby exposing themselves to criticism from both sides. The authors state that the psychiatrists, because of their greater power, often exercise a disproportionately large influence, and that this gives rise to certain difficulties of co-operation in that other groups feel steamrollered and feel that their competence is not put to proper use. The disparity of power also affects the relation between psychiatrists and patients in that the patient’s 6 autonomy and right to have a say concerning his or her care and treatment are not respected, whereby patients often feel that they are not being listened to. The authors conclude that if teamwork is to be successful, it is necessary that greater consideration be shown for different groups’ implicit models and that the patient’s right to participate in the decision-making be taken far more seriously. There are certain important differences between the Warwick study and our own which make direct comparison difficult. For instance, the teams we studied included two professional groups (psychologists and occupational therapists) not included in the English study. Further, our study involved the participation of mental orderlies (Sw. mentalskötare), a group of care staff with a long historical tradition within Swedish psychiatry and who have played a central role particularly in institutional care but for whom there does not appear to be an equivalent in contemporary English community-based psychiatry. Another important difference is that the social workers included in the Warwick study’s psychiatric teams appear to have a much more independent status than their Swedish equivalents. The social workers included in our study are an integral part of the psychiatric clinical organisation, whilst the English social workers come from “outside” and represent the social services rather than psychiatry in the teamwork. If we make an overall comparison of the the results of our study with those of the Warwick study, certain differences emerge fairly clearly. One important difference is that when it comes to the nature, causes and appropriate treatment of mental disorder, the team-members in our study exhibit a far more eclectic and pragmatic position than do their counterparts in the English study. With regard to the aetiology of mental illnesses, the participants in our study tend to look for combinations of biological and psychological or social causes. They can speak, for example, of a particular person’s illness as being probably explicable in terms of a genetically determined vulnerability in combination with the triggering effect of mental or social factors. Furthermore many of our respondents (regardless of professional affiliation) speak of the need of combined treatment strategies, where both medication and psychosocial measures have an important role to play. This means that the clear distinction between the support for one model and that for another such as is to be found among different professional groups in the English study is absent from our study. The difference which Colombo et al. observed between psychiatrists and social workers with regard to the endorsement of the medical model or the social one, and which involved a repudiation of the other model, is barely visible in our study. It can indeed be said quite generally that our respondents’ reasoning about the interpretation and treatment of mental disorders hardly ever had anything to do with the repudiation of one or another way of looking at things. There emerges from our interviews a sort of care-ideological “culture of mutual understanding” not to be found in the Warwick study. The role of mediator, seen as so problematic by the psychiatric nurses in the latter study, is not described in anything like the same terms by the nurses in our study. Further, the endorsement of a “conspiratorial”, anti-psychiatric model which Colombo et al. found in the case of some of their respondents is almost completely absent from our findings. When it comes to joint decision-making there emerges another interesting difference between the two studies. In the English study joint decision-making appears as a comparatively well-defined and familiar phenomenon. The participants discuss its pros and cons with no apparent questioning of what it implies. In our study, however, there is often considerable uncertainty about it. The co-operation in psychiatric teams is for the most part seen as being a question of different professions contributing different knowledge and skills, whilst the making of important decisions is for the most part seen as occurring side by side with this co-operation. For this reason the persons involved often find it difficult to offer clear examples of joint decision-making with good or bad outcome. It seems likely that a closer 7 analysis of these differences presupposes a deeper study of the actual processes of decisionmaking in English and in Swedish team-psychiatry. It is fairly apparent, though, that joint decision-making forms a more clearly articulated part of the ideal image of psychiatric teamwork in English psychiatry than in Swedish, and that practical difficulties having to do with this decision-making come out more clearly in the English study. A third area where there are marked differences between the Warwick study and our own is that of the involvement of patients and next of kin in the teamwork. The former study appears to presuppose that patients and next of kin shall have a very great deal of influence — they are described virtually as members of the pyschiatric teams. In our study, by contrast, there emerges a great deal of uncertainty with regard to such influence. The patients and next of kin often seemed a little bewildered when it came to the part of the interview that concerned their participation in some form of decision-makin, and they were unable to give any examples of decision-making in which they felt they had played a significant part.