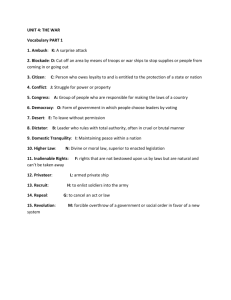

EnlightenedRuleandTy..

advertisement