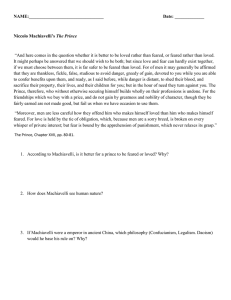

Medieval Sourcebook: Niccolo Machiavelli: The Prince [excerpts

advertisement

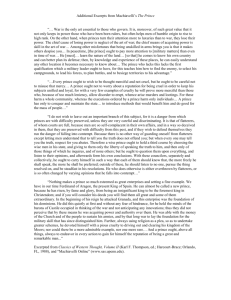

Medieval Sourcebook: Niccolo Machiavelli: The Prince [excerpts], 1513 Niccolo Machiavelli, a diplomat in the pay of the Republic of Florence, wrote The Prince in 1513 after the overthrow of the Republic forced him into exile. It is widely regarded as one of the basic texts of Western political science, and represents a basic change in the attitude and image of government. That Which Concerns a Prince on the Subject of the Art of War The Prince ought to have no other aim or thought, nor select anything else for his study, than war and its rules and discipline; for this is the sole art that belongs to him who rules, and it is of such force that it not only upholds those who are born princes, but it often enables men to rise from a private station to that rank. And, on the contrary, it is seen that when princes have thought more of ease than of arms they have lost their states. And the first cause of your losing it is to neglect this art; and what enables you to acquire a state is to be master of the art. Francesco Sforza, though being martial, from a private person became Duke of Milan; and the sons, through avoiding the hardships and troubles of arms, from dukes became private persons. For among other evils which being unarmed brings you, it causes you to be despised, and this is one of those ignominies against which a prince ought to guard himself, as is shown later on. Concerning Things for Which Men, and Especially Princes, are Blamed It remains now to see what ought to be the rules of conduct for a prince toward subject and friends. And as I know that many have written on this point, I expect I shall be considered presumptuous in mentioning it again, especially as in discussing it I shall depart from the methods of other people. But it being my intention to write a thing which shall be useful to him to apprehends it, it appears to me more appropriate to follow up the real truth of a matter than the imagination of it; for many have pictured republics and principalities which in fact have never been known or seen, because how one lives is so far distant from how one ought to live, that he who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation; for a man who wishes to act entirely up to his professions of virtue soon meets with what destroys him among so much that is evil. . Each person in your group will have a role. Read your role and take notes on the reading as directed to prepare for a group discussion. 1.Discussion Leader: You are responsible for discovering key elements in the reading and coming up with a list of analytical questions for group discussion. What did the text make you think about? What are the main ideas of the reading? What is the historical significance? What questions should you ask to help you comprehend this primary source (can include confusing vocab) 2. Polisher: Identify 2-3 important passages (one from each paragraph) in the reading section and lead your group members in a discussion of the passages. The passages should be interesting, confusing, important. Your notes should include why you selected these passages and 1 question to ask the group about each passage. 3.Linker: Your job is to connect the reading with what you know about the time period of the Renaissance and with today. As you read, write your questions and connections down in your notes. Consider: What links can you make between the reading and the time period, class lessons, current events? What questions do you have about how the text relates to the time period? 4.Summarizer: Your job is to create a graphic organizer that summarizes the main points of the reading. You need to make the organizer easy for the rest of the group to see as you explain it to them. Think about: What are the most important ideas in the reading? Why are they so important? What is the main idea of this reading selection? What questions would you see on an exam about this reading? Hence, it is necessary for a prince wishing to hold his own to know how to do wrong, and to make use of it or not according to necessity. Therefore, putting on one side imaginary things concerning a prince, and discussing those which are real, I say that all men when they are spoken of, and chiefly princes for being more highly placed, are remarkable for some of those qualities which bring them either blame or praise; and thus it is that one is reputed liberal, another miserly...; one is reputed generous, one rapacious; one cruel, one compassionate; one faithless, another faithful.... And I know that every one will confess that it would be most praiseworthy in a prince to exhibit all the above qualities that are considered good; but because they can neither be entirely possessed nor observed, for human conditions do not permit it, it is necessary for him to be sufficiently prident that he may know how to avoid the reproach of those vices which would lose him his state... Concerning Cruelty and Clemency, and Whether it is Better to be Loved than Feared Upon this a question arises: whether it is better to be loved than feared or feared than loved? It may be answered that one should wish to be both, but, because it is difficult to unite them in one person, it is much safer to be feared than loved, when, of the two, either must be dispensed with. Because this is to be asserted in general of men, that they are ungrateful, fickle, false, cowardly, covetous, and as long as you successed they are yours entirely; they will offer you their blood, property, life, and children, as is said above, when the need is far distant; but when it approaches they turn against you. And that prince who, relying entirely on their promises, has neglected other precautions, is ruined; because friendships that are obtained by payments, and not by nobility or greatness of mind, may indeed be earned, but they are not secured, and in time of need cannot be relied upon; and men have less scruple in offending one who is beloved than one who is feared, for love is preserved by the link of obligation which, owing to the baseness of men, is broken at every opportunity for their advantage; but fear preserved you by a dread of punishment which never fails. Nevertheless a prince ought to inspire fear in such a way that, if he does not win love, he avoids hatred; because he can endure very well being feared whilst he is not hated, which will always be as long as he abstains from the property of his citizens and subjects and from their women. Critical Thinking Question: Why was Machiavelli’s advice to leaders appropriate for the time period of the Renaissance?