Research for Decision

advertisement

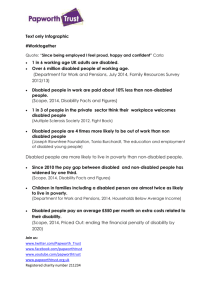

Research for Decision-Makers Issue 50 – March 2013 In this month's bulletin This monthly bulletin provides short summaries of relevant new research and draws out key points for Adult Services in Hampshire. Autism – transition Carers Disabled people - statistics Learning disabilities – crisis – mental health Older people – dementia Older people – social exclusion Palliative care Prevention New research In Brief A recent report on hospice care usefully collates evidence on people’s preferences concerning where they wish to die. It includes views from the general public and data on whether or not people’s requests were met. This includes people in care homes. The report, Current and future needs for hospice care: an evidence-based report, by the Cicely Saunders Institute is available at http://www.helpthehospices.org.uk/ourservices/commission/resources/. On the same theme, My life until the end: Dying well with dementia, published by Alzheimer’s Society, summarises existing evidence from carers, bereaved carers and people with dementia. It highlights that just 6% of people with dementia die in their own home compared to 21% of the population overall. The report is available at http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=1537. Autism – transition Transition to Adult Services and Adulthood for Young People with Autistic Spectrum Conditions Bryony Beresford, Nicola Moran, Tricia Sloper, Linda Cusworth, Wendy Mitchell, Gemma Spiers, Kath Weston and Jeni Beecham SPRU, University of York February 2013 This study took place in five sites. It aimed to investigate the roles of multi-agency transition services in relation to young people with autistic spectrum conditions (ASC), and the arrangements that were in place for planning transitions for young people with 1 and without learning disabilities; explore young people’s and parents’ experiences of planning for transition and making the transition from children’s to adults’ services; explore the costs and outcomes for young people of the transition process. The research sites had been identified as localities that had established multi-agency transition planning processes and systems in place and which had actively developed ASC specific services. A mixed methods approach was adopted including: interviews with managers and practitioners in the five research sites working in transition services or services which support young people and young adults with ASC, including both statutory and non-statutory agencies and organisations; a survey of young people with ASC and parents: both those who were on the cusp of leaving school (defined as ‘pre-transition’) and those who had recently left school and moved into adult services/adulthood (defined as ‘post-transition’); interviews with young adults (18 – 24 years) with High Functioning Autism (HFA) and Asperger’s syndrome (AS); interviews with parents/carers of young people with autistic spectrum conditions (aged 16 – 24 years); and an analysis of the costs of providing transition support in each of the research sites. The survey of parents and young people yielded very low responses rates and was extremely variable between research sites. This meant the researchers could not explore and compare families’ ‘post-transition’ outcomes against the different models of transition planning and support in place in the research sites. In addition, not all research sites provided adequate financial data. This lack of data, coupled with the low response to the family survey, significantly restricted the work they could do on costs. Many of the findings are similar to the findings of our own Autism strategy preconsultation work. Findings include: Some research sites had systems and structures in place that sought to ensure all young people with a diagnosis of ASC were receiving some sort of support during transition. However, in other sites it was evident that young people with HFA and AS were not eligible for support from transition teams and thus were vulnerable to planning and preparing for leaving school with no ASC-specific input or support. Experiences of planning for leaving school were mixed – both for those families who had experienced transition planning within statutory SEN/transition planning processes and for those who had not. The lack of post-school options and, for those ineligible for adult social care, the lack of support was the issue of greatest concern to parents and practitioners. Concerning further education, the greatest area of concern was with regard to suspensions, expulsions and/or simply dropping out of college. These were typically viewed by parents and practitioners as outcomes of colleges failing to properly support young people with ASC and manage any challenging behaviours. This was particularly felt to be an issue in mainstream college settings. The lack of post-school/post-college options was an issue for young people with ASC. The absence of any meaningful daytime occupation was an enormous worry for parents. The accounts of some of the young people with HFA and AS that were interviewed corroborated parents’ views that this had a negative impact on wellbeing. 2 Interviewees agreed that a lack of appropriate employment opportunities, and insufficient support to gain and maintain employment, were key barriers to paid work. Policies and practice with respect to supporting young people with ASC into employment appeared to be specific to localities. Transition teams did not appear to view employment as an outcome in which they actively engaged. The perceived (and actual) role of Connexions varied considerably between sites. There were examples of positive practice from ASC-specific services supporting young people into work. However, there was also evidence to suggest there may be lack of understanding of ASC among Job Centre and Job Centre Plus staff. Community mental health teams and, in some places, specialist ‘Asperger’s teams’, were identified as the first port of call for young adults with HFA or AS who were struggling with the transition to adulthood. All these services provided multidisciplinary, but time-limited, support. The consistent view of interviewees was that, for many young people with ASC, moving into an independent living situation was not appropriate or feasible in the early years of adulthood. The lack of meaningful daytime activities for young adults with ASC placed considerable organisational, time and financial burdens on parents as they sought to ‘create’ a meaningful life for their child. Some third sector organisations were providing day services and peer support opportunities for those with ASC, particularly those with HFA or AS. Some of the young people interviewed were very clear that they preferred spending time in such settings, which they saw as ‘normalising’ them. The report is available online at http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/pubs/pdf/TransASC.pdf. Carers Carers UK Caring & Family Finances Inquiry Carers UK /YouGov February 2013 Two online surveys were undertaken in February 2013 for Carers UK by YouGov as part of Carers UK’s ongoing Caring Family Finances Inquiry. For each of the surveys there were 2073 participants across the UK. The figures in the results have been weighted in order to be nationally representative of all adults in the UK. Findings include: Three quarters (76%) of the adult population would be worried about the financial impact of giving full time care to a family member. Those aged 35 to 54, the age group most likely to be taking on caring responsibilities for older parents, expressed greatest concern - with over half of 35 - 44 year olds (51%) saying they would be very worried about the financial impact on their family if they had to give full time care to a family member. However, the worry also significantly affects younger generations. Four in 10 of those aged 18 to 34 said they would be very worried about how they would cope financially if they had to care for a family member (40%). 67% of UK adults said they either would be unable or would struggle to pay household bills if they had to give up work to care and rely on the current level of state help for carers. 3 Just over 1 in 5 UK adults have seen their work negatively impacted as a result of caring (22%), including 2.3 million who have quit work and almost 3 million who have reduced working hours. The impact was highest amongst 45-54 year olds, where more than 1 in 4 reported that caring had taken a toll on their work (27%). The press releases with information about the surveys are available at http://www.carersuk.org/newsroom/item/3033-research-reveals-over-2-million-quit-workto-care and http://www.carersuk.org/newsroom/item/2961-3-in-4-fear-cost-of-caring. Disabled people - statistics Fulfilling Potential: Building a deeper understanding of disability in the UK today Department for Work and Pensions February 2013 This document presents current data on disability in the UK. It aims to be the most comprehensive overview of the evidence on disability since 2005. As part of the work, the researchers synthesised published research; carried out secondary analysis of surveys including the Life Opportunities Survey (LOS), Family Resources Survey (FRS) and Labour Force Survey (LFS); commissioned focus groups of disabled and nondisabled people undertaken by the Office for National Statistics (ONS); and added questions to the ONS Opinions Survey 2012. Some of the key statistics in the document include: Although the age-specific prevalence of long-term conditions is expected to remain stable over the next few years strong growth is expected in the number of people living with multiple long-term conditions. For example, the number of people with three or more health conditions is forecast to rise by a third by 2018. Whilst the prevalence of mental health conditions has not changed, the perception of mental health conditions has. There has been a change in awareness amongst people themselves, doctors, employers and society. Only around half (6 million) of the 11.5 million people covered by the disability provision in the Equality Act are in receipt of disability-related benefits. Only around 2-3 percent of disabled people are born with their impairment. Some will acquire impairments in childhood (or be diagnosed with an impairment in childhood). Most acquire impairments later in life (for example, 79 percent of disabled people over State Pension age reported that they acquired their impairment after the age of 50), and increasingly after State Pension age (47 percent of disabled people over State Pension age acquired their impairment after the age of 65). Forecasts predict a rise of 86 percent in the number of disabled people aged 65 years and above by 2026 translating into an additional 730,000 disabled people. In addition to this, many people are living longer as disabled people, both those who are disabled in later life and those who are disabled from birth. More than 8 out of 10 people aged 65 or over will need some care and support in their later years. 3.2 million disabled people are in work. 11.5 percent of all employed people are disabled and only 9 percent of working-age disabled people have never worked. 4 15 percent of adults with an impairment provide informal care. Over half (55 percent) of disabled people play an active role in civic society by formal volunteering, civic activism, civic participation and civic consultation. Disabled people along with their friends and families make up a large consumer market. The combined spending power of disabled people in the UK has been estimated to be at least £80 billion a year. Disabled people are more likely than non-disabled people to live in poverty. The levels of aspirations among disabled 16 year olds are similar to those of their non-disabled peers and they expect the same level of earnings from a full-time job. However, by the age of 26 disabled people are nearly four times as likely to be unemployed compared to non-disabled people. Among those who were in employment and with the same level of qualification, earnings were 11 percent lower for disabled people compared to their non-disabled peers. By the age of 26 disabled people are less confident and more likely to agree that ‘whatever I do has no real effect on what happens to me’. At age 16 there had been no significant differences between them and their non-disabled peers on these measures. In 2010, the UK’s employment rate for disabled people was lower than the EU average (41.9 percent compared to 45.5 percent). The employment rates for people with some impairments remain consistently low. For example, people with learning disabilities or mental health conditions have employment rates of less than 15 percent. Disabled people are around half as likely as non-disabled people to hold a degree level qualification (15 percent compared with 28 percent) and nearly three times as likely not to have any qualifications (19 percent compared with 6.5 percent). Most disabled people in work are employed in the private sector. Around 800,000 (26 percent) work in the public sector, about the same proportion as non-disabled people (23 percent). International evidence suggests that the key to achieving job outcomes is a focus on work capacity rather than disability and active engagement with the labour market. Work should pay and provide clear financial incentives to take up jobs. The proportion of social care service users and carers receiving a direct payment has increased from 12 percent in 2010/11 to 14 percent in 2011/12. 25 percent of those aged 18-64 with a learning disability receive a direct payment and 35 percent of carers receive a direct payment. There are over 17,000 organisations providing adult social care employing 1.6 million workers, across the private, voluntary and public sector. Disabled people are more likely to remain single (never marry) or to be divorced or separated. Among those aged 30-44, 36 percent of disabled people remain single compared with 26 percent of non-disabled people. Similarly, for this age group, 19 percent of disabled people are divorced compared with 14 percent of non-disabled people. People with learning disabilities have poorer health than their non- disabled peers. Mortality rates among people with moderate to severe learning disabilities are three times higher than in the general population, with mortality being particularly high for young adults, women and people with Down’s syndrome. 5 Only 7 percent of disabled adults participate in at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity sport three times per week compared with 35 percent of all adults. Since 2005 a higher proportion of people are likely to think of disabled people as the same as everyone else (80 percent in 2011 compared to 77 percent in 2005). There has been an increase in the proportion of people who have friends or acquaintances who are disabled – this has increased from 66 percent in 2007 to 73 percent in 2009. However, in 2011 86 percent of people thought that disabled people need caring for some or all of the time, up from 72 percent in 2009. Around four in ten people (41 percent) in 2011 felt that disabled people cannot be as productive as non-disabled people (compared with 36 percent in 2009). In 1998, almost three-quarters (74 percent) wanted to see more spending on benefits for disabled people, compared to 63 percent in 2008 and 53 percent by 2011. Support for more government spending on those caring for sick and disabled people has also declined from 85 percent in 2008 to 75 percent in 2011. Whilst understanding and tolerance of mental health conditions remained high in 2011, the proportion of adults voicing these tolerant attitudes has decreased since 1994. There has been a significant increase in the reporting of disability in the print media in 2009/10 as compared with 2004/5. During this period, there has been a reduction in the proportion of articles that describe disabled people in sympathetic and deserving terms. This was coupled with an increase in the number of articles documenting the claimed ‘burden’ that disabled people are alleged to place on the economy. Disabled people are significantly more likely to experience unfair treatment at work than non-disabled people (19 percent compared to 13 percent). Motivations for hate crimes experienced by disabled people are not always due to their disability. In 2009/11, 2 percent of all adults interviewed on LOS had been a victim of any hate crime in the past 12 months. Victims were asked what they thought the motivations were for the hate crime they had experienced. For adults with impairment, ethnicity was the most commonly reported motivation for hate crime (27%). Disabled people are more likely than non-disabled people to be a victim of any crime Adults with an impairment have a lower level of social contact (i.e. contact with close friends and relatives) than those without an impairment. For example, adults with an impairment are more likely to have no or just one or two close contacts compared with adults without an impairment (14 percent and 8 percent respectively) 32 percent of disabled people experience difficulties, related to their impairment or disability, in accessing goods or services (goods and services include going to the cinema/theatre/concert, library/art galleries/ museums, shopping, pubs/restaurants, sporting events, using public telephones, websites, a bank or building society, arranging insurance, accommodation in a hotel/guest house, accessing health services/Local Authority services, Central Government services, law enforcement services, or any other leisure, commercial or public good or service). This figure has decreased from 42 percent in 1995. 6 Transport is an important factor in supporting participation but remains a barrier for one in five disabled people The document is available online at http://odi.dwp.gov.uk/docs/fulfillingpotential/building-understanding-main-report.pdf. Learning disabilities – crisis – mental health Mental Health Crisis Information for people with Intellectual Disabilities Colin Hemmings, Shaymaa Obousy ands Tom Craig Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities Volume 7 issue 3 2013 This interesting article presents research looking at whether accessible, portable mental health crisis information was useful for 20 people with mild learning disabilities and mental health problems. Personalized information to help in a crisis was recorded on folded A4 sized sheets that could be carried in a conveniently sized wallet. Nine (45%) participants were men and eleven (55%) were women. Nine were under age of 40 and eleven were aged over 40. Fifteen (75%) were of white UK or Irish ethnicity and five (25%) were of Black UK or African or Asian ethnicity. Four (20%) were in independent accommodation with outreach support whilst sixteen (80%) were in staffed accommodation of various forms. The participants were told that certain basic information would be on their crisis information. This consisted of their name and address and contact numbers for a key person they would like to have contacted in the event of a crisis, their GP and out of hours GP service, the local Community Learning Disabilities Team, the local hospital Accident and Emergency department and Social services including the out of hours contact number.. They could choose whether they wanted to have a picture of themselves on a plastic identity card to be kept with the crisis information. They were also asked if they wanted the following information included: their mobile telephone number, mental health history, physical health, medications, allergies and contact numbers of professionals involved in their care. They were then asked if they wanted the following information included and if so, asked to give details: What happens when I first become unwell...What I think would help me if I am in a crisis...What doesn't help me if I am in a crisis...Which things or belongings are important to me...How I would like people to talk to me...What makes me sad or unhappy...What makes me happy and cheerful...What makes me irritable or angry...What makes me worried or anxious...What makes me calm or relaxed...What makes me scared or frightened...Any other important information I would like people to know. The completed crisis information was colour printed on A4 paper tri-folded down to fit in provided leather wallets, suitable in size to be kept in pockets or bags. Findings include: Seventeen of the twenty participants (85%) nominated a carer or relative to assist them in the completion of their crisis information. The majority wanted to include a picture card and their own mobile phone number if they had one. Nearly all wanted to include contact numbers of professionals involved in their care (95%), details of their mental health (95%), physical health (90%) and current medications (85%). 7 The majority wanted to include the following items: How I would like people to talk to me (95%), What makes me calm or relaxed (95%), What happens when I first become unwell (90%), What I think would help me if I am in a crisis (90%), What makes me happy and cheerful...(90%), Which things or belongings are important to me (90%), What makes me irritable or angry (85%), What makes me sad or unhappy (80%), What makes me scared or frightened (80%), What doesn't help me if I am in a crisis (70%), What makes me worried or anxious (65%). The item that produced the most detailed response was How I would like people to talk to me. The details given included: "People being kind", "Please talk softly and calmly", "I want people to talk to me politely, no big words, not talking too much, going on and on", "Slow and simple, I don't like too many questions", "Not too many people, two or three people and that's enough." The participants provided several comments on what they would not like to happen in a crisis. One said, “I don’t like people talking about my mum because she is dead”. Participants were less inclined to include information about allergies because the majority did not have any and so possibly did not understand the purpose of recording this information. It can be speculated also that they were less inclined to include negative things in their crisis information. Several of the participants did not want to include information about things that frightened or scared them or made them feel unhappy, sad, or anxious. Only four participants had had a mental health crisis in the preceding six months before receiving their crisis information. All felt that not enough had been known about them by the staff who saw them. Three quarters of the participants carried their crisis information wallets on a daily basis for six months before evaluation. They and their carers expressed positive feedback about them carrying the crisis information. No one carrying the information actually experienced a mental health crisis in the six months follow up period so their usefulness in such crises could not be evaluated. However, they were unexpectedly used in other non-mental health settings and reported to have been helpful. Places used included a GP practice, an Accident and Emergency Department and an employment advisory service. Two of the participants would not take their crisis information wallets out of the house as they wanted to keep them safe. Three participants lost or mislaid theirs. The participants clearly liked having the crisis information wallets and they seemed to enhance self- esteem and confidence. 19 out of 20 wanted to continue to use them after the six-month evaluation period. A number of carers commented favourably that the crisis information wallets were portable, gave reassurance and would be available without any prior planning. Care staff suggested they may be useful in other settings, e.g. if the person started to panic in a shopping centre. The crisis information was not expensive, difficult, or time-consuming to produce once a template had been established. In clinical practice, it would entail at least a meeting of approximately 30 minutes for the person to choose what would be in their crisis information and to have their picture taken if they chose to have an identity card as well. Updating the crisis information would take additional time when changes were necessary although care staff and key workers may often be able to do that. The report is available to people with SCIE Athens account at 8 http://www.emeraldinsight.com/journals.htm?issn=2044-1282&volume=7&issue=3 or on request from Rachel Dittrich, rachel.dittrich@hants.gov.uk. Older people – dementia Study of the use of antidepressants for depression in dementia: the HTA-SADD trial – a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of sertraline and mirtazapine Banerjee S, Hellier J, Romeo R, Dewey M, Knapp M, Ballard C, et al. Health Technol Assess 2013;17(7) February 2013 This is yet another report showing that antidepressants should not be given to older people. It reports on a randomised-controlled trial of the two antidepressants most likely to be prescribed to people with Alzheimer’s - sertraline and mirtazapine. The trial was double blind: the medication and placebo were identical for each antidepressant. Referring clinicians, research workers, participants, pharmacies and statisticians were not told which was antidepressant and which was placebo. Participants were recruited from community old-age psychiatry services in nine English centres (including Southampton). 326 people were randomised to one of three groups – 111 to receive placebo, 107 to receive sertraline and 108 to receive mirtazapine. Groups were evenly matched, and the majority of participants were female, with a mean age of 79 years; 146 (45%) were married. Findings were: There was a strong consistent pattern of improvement in the depression at 3- and 9month follow-up for participants. However, this study gives strong evidence that this improvement is not attributable to antidepressants: improvement was across all groups. In other words, the trial shows the antidepressants appear to be no more effective than placebo. What this study cannot tell us is if this improvement is a function of the non-drug ‘treatment as usual’ by these old age psychiatric services, or due to things such as regression of the mean or the Hawthorne effect. The placebo group had fewer adverse reactions (29/111, 26%) than the sertraline (46/107, 43%) or mirtazapine (44/108, 41%) groups. Fewer of the reactions were severe. The paper is available online at http://www.hta.ac.uk/fullmono/mon1707.pdf. Older people – social exclusion Understanding material deprivation among older people Anna Bartlett, Claire Frew and Joanne Gilroy Department for Work and Pensions March 2013 This report provides in-depth quantitative analysis of the material deprivation and low income experiences of older people. It is based on 2009/10 - 2010/11 data from the Family Resources Survey, a major survey completed by 20,000 households in the UK. 9 Material deprivation is measured in this survey by asking people if they have access to the following things: At least one filling meal a day Go out socially at least once a month See friends or family at least once a month Take a holiday away from home Able to replace cooker if it broke down Home kept in a good state of repair Heating, electrics, plumbing and drains working Have a damp-free home Home kept adequately warm Able to pay regular bills Have a telephone to use, whenever needed Have access to a car or taxi, whenever needed Have hair done or cut regularly Have a warm waterproof coat Able to pay an unexpected expense of £200 The respondent is defined as being deprived for that item if they lack it for financial or non-financial reasons, but not if they choose to not have access to/own that item. Key points include: The vast majority, around 80 per cent, of pensioners do not experience relative poverty or material deprivation. More than half (over 5 million, or 51 per cent) of all pensioners do not report any level of material deprivation. A further 40 per cent (around 3.9 million) report that they lack up to 3 of the 15 items; this means that they experience some (small) level of material deprivation, but are not deemed ‘materially deprived’ according to the Family Resources Survey definition. 9 per cent (800,000) of pensioners were materially deprived (according to the Family Resources Survey definition) in 2010/11. The majority of those pensioners who are materially deprived lack between 3 and 6 items. These individuals tend to be experiencing some level of social and financial deprivation. They tend to be lacking the ability to replace a cooker, deal with an unexpected expense of £200 and take a holiday away from home. Social deprivation is the most common form of material deprivation for pensioners, with over 90 per cent of materially deprived pensioners lacking a social item (e.g. being able to go on a holiday, or see friends and family regularly). Only 2 per cent of pensioners do not have a warm waterproof coat, with the most common response for not having one being ‘no money for this’. 10 Only 1 per cent of pensioners do not have at least one filling meal per day, with the responses here for this being ‘health/disability prevents me’ and ‘not something I want’. Lacking access to a telephone, is experienced by 3 per cent of all pensioners. Disability appears to be one factor that is associated with material deprivation. This suggests that disabled pensioners have difficulty in being able to access certain goods & services. Housing tenure is also an important factor, with those pensioners living in socialrented accommodation appearing to be at greater risk of material deprivation than those who own their own homes. The most common reasons given by pensioners for being materially deprived vary by item and degree. Not being able to afford an item and health/disability issues affecting them are some of the most common reasons cited. The report is available online at http://research.dwp.gov.uk/asd/asd5/ih20132014/ihr14.pdf. Prevention Prevention services, social care and older people: much discussed but little researched? Jon Glasby, Robin Miller and Kerry Allen University of Birmingham March 2013 This briefing presents findings from a survey sent to Directors of Adult Social Services in nine Local Authorities (LAs) to identify what they viewed as their top three investments in prevention services for older people. Interviews took place with the leads for each intervention. The researchers also reviewed the local evidence as to whether these interventions lead to a delay or reduction in the uptake of social care services. I would treat this briefing with a bit of caution: the researchers say that formal research evidence shows that the three interventions discussed can have an impact - this is true, but, apart from for reablement and some aspects of telehealth, there is generally little or no clear evidence they have a preventative impact. Findings include: All of the nine LAs surveyed reported that reablement was one of their ‘top’ approaches to prevention. Reablement services were generally directly provided by LAs. Most worked with older people in general but a few focused on those with particular conditions, such as dementia. They were all based around core teams of specialist home carers with input from occupational therapists. There were also examples of other health and social care professionals being integrated within the reablement service. Telecare, telehealth and/or other technology based interventions were amongst the top three interventions in six Las. Information and advice services were amongst the top three in three authorities. In all cases these were provided by a third sector organisation, and older people and/or their carers could self-refer. There were also links to LA call centres. 11 LAs were often influenced by evidence and/or advice provided by national and regional sources on the best way to invest in prevention. This included findings from central government-funded pilot initiatives and reports from third sector organisations with a focus on the needs and wishes of older people. Many of the reablement and telecare services, in particular, had begun with pump priming money from the Department of Health. Formal research studies in relation to reablement, telecare, and information and advice services suggest that they can have positive impacts on prevention. However, the number and scope of such studies is limited and there continues to be a considerable evidence gap. Local analysis of current and predicted need referral patterns and current use of services were often part of the decision-making process. Views of older people and professionals were sought through both formal consultations and anecdotal feedback. Learning from the experiences of LAs that had already developed a similar service was also seen as helpful. However, decisions on investing in prevention were not always evidence-based. Other factors could influence how local funding was spent. This included political commitment to maintaining the role of a local third sector provider and/or retaining inhouse services and the practice based experience of senior members of staff. Reablement services were clear about the outcomes that they were expected to achieve by the LA and were given targets to reduce the amount of social care support required by older people accessing their service. They also asked older people whether their personal outcomes were met. LAs were generally not able to state the outcomes they expected from other interventions clearly, and these services often did not have processes through which older people could set their own outcomes. Some interventions worked on the basis that if the older people perceived the service had been useful then it was achieving the right outcomes. Local evidence indicated that by the time they were discharged from reablement services between 50–90% of older people (depending on the LA concerned) needed less or no support than when they initially contacted the service. Local evidence also revealed that many of older people’s personal outcomes were met. These findings reflect those of formal research studies that have shown that reablement services can improve outcomes and can sometimes create efficiencies. The briefing is available online at http://sscr.nihr.ac.uk/PDF/Findings_17_preventioninitiatives_web.pdf. Further outputs from the project will be available shortly. 12