CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OUTLINE

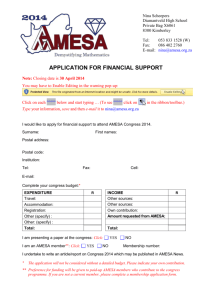

advertisement