2 Country Characteristics

advertisement

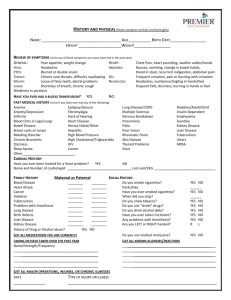

Coordination and Management of Chronic Conditions in Europe – The Role of Primary Care Position Paper 2008 Second draft prepared for the European Forum for Primary Care by Stefan Greß (University of Applied Sciences Fulda, Germany)* Caroline Baan (RIVM, Netherlands) Michael Calnan (University of Kent, England) Toni Dedeu (BRIHSSA Barcelona, Catalonia) Peter Groenewegen (NIVEL, Netherlands) Helen Howson (Welsh Assembly Government, Wales) Simo Kokko (STAKES, Finland) Luc Maroy (NIHDI, Belgium) Ellen Nolte (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, England) Marcus Redaèlli (University of Witten-Herdecke, Germany) Osmo Saarelma (Health Center of Espoo, Finland) Norbert Schmacke (University of Bremen, Germany) Klaus Schumacher (IMTG, Austria) Evert Jan van Lente (AOK-Bundesverband, Germany) Bert Vrijhoef (University of Maastricht, Netherlands) *corresponding author (stefan.gress@hs-fulda.de) Abstract Health care systems in Europe struggle with inadequate coordination of care for chronic conditions. Moreover, there is a considerable evidence gap in treatment of chronic conditions, lack of self-management, variation in quality of care, lack of preventive care, increasing costs for chronic care and inefficient use of resources. In order to overcome these problems, several approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions have been developed in European health care systems. These approaches endeavour to improve selfmanagement support for patients, develop clinical information systems and change the organization of health care. Changes in the delivery system design and the development of decision support systems are less common. As a rule, the link between health care services and community resources and policies is missing. Most importantly, the integration between the six components of the chronic care models remains an important challenge for the future. We find that the position of primary care in health care systems is an important factor for the development and implementation of new approaches to manage and coordinate chronic conditions. Our analysis supports the notion that countries with a strong primary care system tend to develop more comprehensive models to manage and coordinate chronic conditions. Acknowledgements For their support, the authors would like to thank Diederik Aarendonk from the European Forum for Primary Care, Ulrike Fuchs and Hendrik Siebert from the University of Applied Sciences Fulda. 2 1 Introduction Chronic conditions pose an important challenge to European health care systems. According to the WHO definition, chronic conditions are health problems that require continuous management over a period of years or decades (World Health Organization 2003). Moreover, these conditions require coordinated input from a wide range of health professionals (Nolte, McKee 2008a). New models of providing health care are being introduced in European countries in response to a set of problems that are evident to some degree in all health care systems. These problems include the overuse, underuse and misuse of health care services, uncoordinated arrangements for delivering care, bias towards acute treatment, and the neglect of preventive care (Vrijhoef et al. 2001). The models to improve care for chronic conditions are as diverse as health care systems are different. While some countries have introduced disease-specific programmes, other countries are struggling with approaches which are more comprehensive. The aim of this position paper is to analyze the experience of a number of sample countries which are currently trying to reorganize the organization of health care delivery in order to make the management and coordination of chronic conditions more feasible. In particular, we discuss the role of primary care in this process. We use the terms management and coordination in a pragmatic way because in our view they refer to a systematic and organized approach to provide care for chronic conditions (management) as well to an approach which overcomes the segmentation and fragmentation of health care delivery in many countries (coordination). We started out by analyzing the introduction of disease management in a number of European countries – specifically in Germany and the Netherlands. While disease management has been developed an applied in the United States for several decades, the introduction of disease management programmes in Europe is a comparatively new development. However, in the process of analyzing this specific concept of tackling chronic conditions, the limitations of disease management became obvious. Disease management constitutes a single-disease approach and tends to neglect co-morbidities. Moreover, by definition, disease management becomes active only after individuals have developed a particular chronic disease. As a consequence, disease management is unable to prevent chronic conditions. Finally, we found that disease management has a strong American managed care subtext which makes implementation of disease management difficult in a number of European countries. As a 3 consequence of these limitations we extended the scope of the paper towards the management and coordination of chronic conditions in Europe and the particular role of primary care. We do not consider this position paper as the end of a process. Instead we hope that our input will facilitate further discussion about the response of health care systems to the challenge of managing and coordinating chronic conditions. Each country has a very unique health care system with very individual characteristics and need to develop an individual response. Therefore, the position paper has been prepared by experts with a variety of professional backgrounds from a variety of countries. Moreover, the structure of the paper reflects the differences between countries. In the next section we summarize the country characteristics of our eight sample countries. In section 3 we analyze the problems which have led to the management and coordination of chronic conditions. We find that problem definition varies between countries but still many problems are prevalent in more than one country. Section 4 discusses which country has chosen which approach to coordinate and manage chronic conditions. Again, there is considerable variation. In the final section we analyze the implementation problem. We distinguish between a bottom-up approach and a top-down approach to implement the management and coordination of chronic conditions. Moreover, we find that financial incentives are an important tool to facilitate the implementation of these approaches. Section 6 concludes and summarizes our findings. 2 Country Characteristics This position paper analyzes approaches towards the management and coordination of chronic conditions in selected European countries. These countries differ with regard to the predominant mode of financing and with regard to the role of primary care. We have chosen these characteristics of health care systems because they constitute important institutional background for the implementation of improved management and coordination of chronic conditions. We assume that is makes a difference whether health care finance is primarily taxbased or primarily based on health insurance contributions. From the view of policy makers, the implementation of any health care reform most of the time is easier in tax-based national health systems. The line of command is more direct. Moreover, competitive social health insurance systems with inadequate risk adjustment face the problem of risk selection which from the insurer’s point of view might be more profitable than investing in the quality of health care delivery. At least in the German case financial disincentives for health insurers – which have been the consequence of a poor risk adjustment system – have been a major 4 obstacle to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions (Greß et al. 2006). Finally, we consider the role of primary care in the health care system of our sample countries as a major institutional determinant for the management and coordination of chronic conditions. We assume that a strong primary care system is able to manage and coordinate chronic conditions more effectively than a weak primary care system. The strength or weakness of a primary care system is determined by a number of components such as regulation, financing, primary care provider, access, longitudinality, first contact, comprehensiveness, coordination, family orientation and community orientation (Macinko et al. 2003). Table 1 shows that our country sample represents four countries which are financed primarily by taxes (Catalonia, England, Finland, Wales) and four countries which are financed primarily by social health insurance contributions (Austria, Belgium, Germany, Netherlands). Within the group of social health insurance countries, three countries feature competing health insurers (Belgium, Germany, Netherlands) while health insurers in Austria do not compete. According to the classification by Macinko et al. (2003) Catalonia, England, Finland, the Netherlands and Wales have a strong primary care system. Austria, Belgium und Germany have – according to the same classification – a rather weak primary care system. Table 1: Country Characteristics Main source of financing Competing health insurers Strong primary care system Austria Social insurance No No Belgium Social insurance Yes No Catalonia Taxes No Yes England Taxes No Yes Finland Taxes No Yes Germany Social insurance Yes No Netherlands Social insurance Yes Yes Wales Taxes No Yes 3 Problem definition Although all health care systems in our sample are struggling with a variety of problems which have led to a variety of approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions, some problems are in some countries more important than others. Table 2 5 lists the problems identified by the literature and the expert opinions within our group. The first problem – bridging the evidence gap – refers to practice variations which are not in line with the existing evidence. Inadequate coordination of between health services in particular refers to problems between primary care and secondary care. However, inadequate coordination between health professions – such as physicians and nurses – can also be a major problem. The same is true for poor coordination between health care and social care. In contrast, the lack of self-management concerns the missing support for individual activities of the patient in order to improve self-management of her chronic condition. The variation of quality of care – between patient groups and regions – primarily is a matter of fairness. In contrast, the problems of increasing costs for chronic care and the inefficient use of scarce resources primarily have its foundation in an economic line of reasoning. The lack of preventive care refers to primary prevention (measures to reduce risk behaviour or risk factors for a chronic condition), to secondary prevention (identification and treatment of asymptomatic persons who have already developed risk factors or preclinical chronic conditions but in whom the condition has not yet become clinically apparent) and to tertiary prevention (intervention that aims to mitigate health consequences of a clinical chronic condition).1 The perception of problems may considerably, because health professionals, patients and policy makers have different views. In Austria, five problems can be identified as primary motivation to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions. Bridging the evidence gap is one important issue in Austria. There exist a few guidelines but they are not agreed upon nationally. Moreover, coordination between health services is inadequate. What is more, there is hardly any coordination between health services and social care. Lack of self-management is evident, since patients in Austria are not used to get involved in the care progress and there are no incentives to do so. Moreover, there are no concepts for health prevention and promotion. Regional variation in the quality of care is considerable. In Belgium the primary problems are considered to be insufficient coordination of care between health services – in particular between primary care and secondary care – and variation in the quality of care. These problems have been analyzed in detail for diabetes (Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de gezondheidszorg 2006) but they are also prevalent for other chronic conditions. 1 The definition of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention is based on (Reisig, Wildner 2008). 6 In Catalonia…. In England the problem definition depends on the perspective. From a health system perspective the variation of quality of care, the increasing costs for chronic care and the inadequate coordination of care between health services are predominant. From the view of the patient, the two latter problems are most important. The view of the professional varies: Bridging the evidence gap, lack of self-management and lack of preventive care are most important. In Finland, primary problems which have led to the development of models to improve the management and coordination for chronic conditions are considered to be the lack of selfmanagement, the ineffective use of resources and insufficient coordination between health professionals in primary care. From a system perspective, over- and underuse of health services is prevalent. From the view of the patient, the process of care lacks coordination and patients are not active. From the view of health professionals, care is based too much on professionals and patients’ resources are not used. Moreover, resources of nurses could be used more extensively and coordination between nurses and general practitioners could be improved. In Germany, the onset of the development of new approaches towards a better management and coordination for chronic conditions can be dated to a report of the advisory body which reports to the Ministry of Health. The Advisory Council in its seminal report analyzed extensive overuse, underuse and misuse of health services in the German health care system – particularly in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of chronic conditions (Advisory Council for the Concerted Action in Health Care 2001). According to the Council, the primary causes for the overuse, underuse and misuse of services were inadequate coordination between health care services, in particular between primary care and secondary care, negligence of preventive services, insufficient self-management of patients and practice variations which were not in line with existing evidence. Moreover, inadequate risk adjustment made it for health insurers financially harmful to invest in improving the management and coordination of chronic conditions (Busse 2004, Greß et al. 2006). In the Netherlands, stakeholders – in particular policy makers, health professionals and academics – are motivated by all problems listed in Table 2. However, the primary motivations for the improved management and coordination of chronic conditions are the 7 inadequate coordination of care between health services and increasing costs for chronic care.2 Moreover, variation in the quality of care is also a primary problem in the Netherlands. In Wales… Table 2: Problem Definition Problem AUT BEL CAT ENG FIN GER NL Bridging the evidence gap P S P S P S Inadequate coordination of care between health services P P P P P P Lack of (self)management P S P P P S Variation in quality of care (patient groups and regions) P P P S S S Increasing costs for chronic care/inefficient use of resources S S P P S P Lack of preventive care P S P S P S WAL P: Primary problem which led to improved management and coordination of chronic conditions S: Secondary Problem Of course our survey of problems which led to the development of improved management and coordination of chronic conditions in our sample health care systems is not a representative one. However, it shows that inadequate coordination of care between health care services is an important problem in all countries which are represented by our group. This is an important finding from the view of primary care, since coordination between primary care and secondary care and coordination between professions within primary care seems to be ubiquitous problem. Our analysis also shows that other problems – bridging the evidence gap, lack of self-management, variation in quality of care, lack of preventive care, increasing costs for chronic care and inefficient use of resources – are not unique but concern at least half of the countries in our sample. 2 Source: Letter on programmatic approach of chronic diseases by Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport. The Hague, 13 June 2008. 8 4 Components Approaches towards improving the management and coordination of chronic conditions in our sample countries vary considerably. We have categorized these approaches by referring them to Wagner’s chronic care model (Wagner et al. 2001). The chronic care model can be considered as a guide towards improving the management and coordination of chronic conditions within primary care (Bodenheimer et al. 2002a). The six components of the model are closely intertwined. The model suggests that improving and integrating these components is the key towards improving the management and coordination of chronic conditions. It is important to note that “the model does not offer a quick and easy fix; it is a multidimensional solution to a complex problem (Bodenheimer et al. 2002a: 1776).” Existing evidence shows that individual components of the model are effective tools to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions in terms of quality of care and patient outcomes (Bodenheimer et al. 2002b, Zwar et al. 2006). However, the evidence remains inconclusive on the impact of applying the model as a whole. The same is true about the question which components in what combination achieve the greatest improvement. Models that adopt an unambiguous patient-oriented approach are likely to have the greatest effects on patient outcomes (Nolte, McKee 2008b). We have gathered a number of approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic care in our European sample countries. It is important to note that this is not a full inventory of all approaches in the respective country. The six components and their application in each country are listed in table 3. Community resources and policies are an integral part of the chronic care model, because chronic care takes place in “trigalactic universe” – the community, the health care system and the provider organization. To improve chronic care, links towards community-based resources need to be established. Health care organization in terms of provider organization and reimbursement environment is another important component of the chronic care model. Financial incentives need to be in line with the development of chronic care. A key component of the chronic care model is selfmanagement support. Self-management support entails helping patients and their families obtain the skills and confidence to manage their chronic condition, providing selfmanagement tools and assessing problems and achievements on a regular basis. Moreover, the chronic care model also demands change in the delivery system design by creating practice teams and a division of labour between physicians other health professionals such as nurses. Furthermore, evidence-based guidelines provide clinical standards for high-quality chronic 9 care and decision support for health professionals. Finally, clinical information systems supply primary care teams with feedback, remind them to comply with practice guidelines and provide registries for planning individual and population-based care (Bodenheimer et al. 2002a, Wagner et al. 2001). Table 3: Components of the Chronic Care Model Component AUT BEL Community resources and policies Health Care Organization Selfmanagement Support Delivery system design No systematic implementation of components of the chronic care model (yet) Clinical information systems Systematic implementation of all components of the chronic care model (implementation starting after 2009) Decision support CAT ENG FIN GER NL WAL - - X X (X) (X) X X X X - X X X X X - X In Austria and Belgium, initiatives for improving the management the management and coordination of chronic conditions are in a very early stage of development. In Austria, some local or regional efforts in establishing components are under way, but not in a coordinated way and not following a model. In Belgium, health care providers (general practitioners and specialists) and health insurers have in the summer of 2008 negotiated a contract to introduce an integrated system (“care pathways”) which is based on all six components of the chronic care model. The system will start in the beginning of 2009 (diabetes and chronic renal insufficiency). Initiatives in Catalonia… In England the government has launched a custom-built model which was designed to help health and social care organizations to improve care for people with chronic conditions. The model built on approaches such as the chronic care model which adapted to the values and health care system of English NHS. In Finland, initiatives are developing on the level of the municipalities. The approach in Espoo includes five components of the chronic care model. Health professionals have 10 financial incentives for reaching specific goals such as disease specific parameters and process indicators. Patients are provided with tools for self-assessment and receive support for using self-management tools. Self care service points and electronic consultations supplement face-to-face consultations. Division of labour between health professionals is carefully planned. Joint electronic records are available for the entire practice team. Evidence-based clinical guidelines are available electronically for every health professional. In Germany and the Netherlands, approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions so far have been primarily based on disease management. In Germany, disease management has been based on three components of the chronic care model: changes of financial incentives for health insurers and consequently for physicians (see section 5), improvement of self-management support for patients and clinical information systems. The German experience is a good example for physician’s resistance against the introduction of evidence-based guidelines. Physicians were – and to a certain degree still are – afraid that the use of evidence-based guidelines in disease management will lead to a loss of professional autonomy. Physician associations even were asking their members to boycott the introduction of disease management (Greß et al. 2006). However, since third-party payers are paying additional fees for the participation of physicians in disease management, the boycott was not successful. Still, changes in health care organizations are limited to financial incentives. The organization of health care remains largely unchanged. In particular the segmentation and fragmentation between primary and secondary care remains a major problem for improving the management and coordination of chronic conditions in Germany. Disease management provides only weak links between primary care and secondary hospital care. Hospitals play a major part only in conditions such as breast cancer where surgery is involved. Moreover, the development of collaborative models of providing health care is still a matter of contention within primary care. Therefore, disease management in Germany is focused almost exclusively on general practitioners and specialists (endocrinologists; cardiologists; pneumologists and specialists for paediatrics and gynaecologists) in outpatient care. Physicians are extremely reluctant to delegate responsibilities to other health care professionals such as specialized nurse practitioners. Finally, the integration of community resources and the development of decision support do not yet play a major role in disease management. Still, disease management in Germany seems to improve the management and coordination of patients with chronic conditions. The results of the study by Szecsenyi et al. (2008) show that changes in daily practice which have been established by disease management are 11 acknowledged by patients “as care that is more structured and that reflects the core elements of the chronic care model and evidence-based counselling to a larger extent than usual care (Szecsenyi et al. 2008: 1).” Another study found that patients enrolled in disease management programmes encounter less complications than patients in usual care (Ullrich et al. 2007). In contrast to Germany, in the Netherlands the design of disease management initiatives in the Maastricht region is based explicitly on all six components the chronic care model. The components of these programmes in Maastricht include the establishment of collaborative teams which consist of medical specialists, general practitioners, and nurse specialists. Tasks and responsibilities of each type of health care provider in the multi-disciplinary teams were described in a protocol (Steuten et al. 2006). This protocol was based on international treatment guidelines and on the Dutch guidelines for general practitioners. Based on a patient assignment algorithm, the patient population was stratified according to disease complexity. Patients with a low-level disease complexity were assigned to the GP and non-specialized nurse practitioners while patients with medium-level disease complexity were assigned to specialized nurse practitioners. Only patients with a high-level disease complexity were assigned to medical specialists. Nurse specialists independently performed diagnostic and therapeutic tasks. Moreover, they used their nursing skills to improve patient education and promote self-management. Specialized nurse practitioners also served as a link between primary care and secondary care, since they were employed by hospitals but consulted with patients in GP’s office (Steuten et al. 2007). This arrangement seemed to work rather well. Several evaluations of the Maastricht disease management programmes have shown that patient subgroups which were treated by specialized nurse practitioners seem to have benefited most in terms of clinical outcomes, health-related quality of life and patient selfmanagement. Moreover, adherence to guidelines – in terms of number of consultations provided and type of medication prescribed – was highest in the group treated by specialized nurse practitioners such as diabetic nurse specialists (DNS) and respiratory nurse specialists (RNS) (Steuten et al. 2006, Steuten et al. 2007). This is an important finding, since at least in the Dutch context “the stratification of the patient population by disease severity and the key role of the DNS within the collaborative practice model are the most important differences with usual care. The increased attention to patient education and self management probably plays an important role herein, as does the combination of nursing and medical skills of the nurses (Steuten et al. 2007: 1118).” Still, for at least two reasons the Maastricht example does not fully comply with the chronic care model. First, financial incentives in the organization of health care remained unchanged. This makes it difficult to implement approaches similar to 12 the Maastricht experience elsewhere in the Netherlands. Second, the integration of the six components remains incomplete and continues to constitute an important challenge. Initiatives in Wales… 5 Implementation We have shown in section 4 that new approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions require changes in the organization of health care. Therefore, barriers to implementation are to be expected. Third-party payers might be reluctant to pay for the initial investment. Physicians might be reluctant to adhere to evidencebased guidelines and to share care with other health care professionals – as the German example shows quite clearly. Last but not least patients might distrust new approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions as possible tools designed to economize health care. As a consequence, implementation of new models of providing health care needs to be considered carefully. In the European context, two approaches towards implementation can be distinguished. The top-down approach is represented by the German and the English example while the bottomup approach is represented by countries such as Austria, Catalonia, Finland and the Netherlands (for an overview see table 4). The top-down approach is characterized by implementation on a national level, national regulation and national funding. In contrast, the bottom-up approach is characterized by local or regional initiatives within the existing institutional and legislative framework. The main problem of this approach is sustainable funding, since these approaches are mostly financed by one-time grants or short-time contracts. 13 Table 4: Implementation Bottom-up Top-Down Austria X Belgium Catalonia (X) Financial incentives for physicians and patients (in development) X Financial incentives for physicians (pay-forperformance) Financial incentives for primary care providers (pay-for-performance) X Germany Netherlands Financial incentives for physicians and patients X England Finland Instruments and Incentives X X Financial incentives for physicians, patients and health insurers (X) Financial incentives for primary care providers (in development) Wales X X: in place; (X) in development. In Germany, several legislative changes in 2002 had the purpose to neutralize incentives for competing health insurers to select risks and to provide incentives for health insurers to actively manage and coordinate chronic conditions. Most importantly, health insurers were given financial incentives set up disease management for a number of chronic conditions. The tie-in between risk adjustment and the enrollment of patients in disease management in German social health insurance is unique. Health insurers receive higher risk-adjusted payments for patients who are enrolled in a disease management programme. Enrollment for patients is voluntary; the programmes need to be certified by a regulatory agency. Evaluation and re-certification are mandatory. Health insurers face considerable financial incentives to set up as many disease management programmes as possible as fast as possible in order to attract as many chronically ill patients as possible. As a consequence, health insurers need to contract as many physicians as possible in order to convince patients to enroll – which they did by providing considerable financial incentives (Greß et al. 2006, Stock et al. 2006, Stock et al. 2007). In 2007 more than 3.3 million patients have been enrolled in disease management programmes in Germany – about two thirds of them in a disease management programme for diabetes mellitus type 2 (Ullrich et al. 2007). Financial incentives for health insurers to continue disease management will change after the introduction of health-based risk adjustment in 2009. After that, health insurers will receive higher payments for chronically ill 14 patients even if they are not enrolled in a disease management programme. As consequence, health insurers will have financial incentives to invest in other models of providing care for chronically ill patients as well. The advantages of the top-down model – illustrated by the German example – are obvious: By providing considerable financial incentives to third-party payers and physicians it was possible to set up disease management programmes rather rapidly and rather extensively on a national level. Moreover, physicians need to adhere to evidence-based guidelines in order to participate in disease management programmes. However, the disadvantages are evident as well. The introduction of disease management programmes in the German context has not been based on evidence on the clinical and economic consequences of disease management. Moreover, little is known whether physicians indeed adhere to evidence-based guidelines. The bottom-up approach is illustrated by the Dutch example. In the Maastricht region, shared care models and disease management programmes have been implemented since 1997 in a slow and rather deliberate process. The consequences of shared care models and disease management programmes have been evaluated on a regular basis. The shift from shared care to a disease management programme in Maastricht was supported by a demand form general practitioners for the specialized nurse practitioners to expand their role. This demand was supported by evidence, since the shared care model was beneficial in terms of both process and outcomes (Vrijhoef et al. 2001). While the implementation of shared care and disease management programmes seems to be rather successful regionally, the link towards an introduction of disease management programmes on a national level is still missing in the Netherlands. This link may be provided by introducing financial incentives for introducing disease management programmes. More specifically, in the Netherlands an experiment for the introduction of disease management programmes for diabetes has started in the primary care setting (lasting from 2006-2009). In this experiment, diabetes care groups are created. These groups negotiate with health insurers about a fee for diabetes care in the primary care setting and what type of care has to be provided for that fee. After the conclusion and evaluation of this experiment, the Dutch government intends to introduce this new financial incentive on a national level in order to provide financial incentives for the introduction of disease management programmes – not only for diabetes, but for other chronic diseases as well. The advantages of the bottom-up approach of implementing of new approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions are twofold: First, it is possible to 15 develop this new model of providing health care on a step-by-step basis and to adopt it to specific institutional, social and cultural circumstances. Second, by evaluating the process of implementation on a regular basis, it is possible to provide decision makers with rather hard evidence about the clinical and economic consequences of new model of providing health care for the chronically ill. One important disadvantage of the bottom-up approach is obvious as well. Regional experiments – even if they are successful – are not adopted automatically on a national level. The development of financial incentives for health care providers may provide the link between regional and national implementation. 6 Conclusion Health care systems in Europe struggle with a number of problems which have led to a variety of approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions. Inadequate coordination of care for chronic conditions between health care services seems to be a predominant issue – which is an important finding from the view of primary care. Other important problems include a considerable evidence gap, lack of self-management, variation in quality of care, lack of preventive care, increasing costs for chronic care and inefficient use of resources. In order to overcome these problems, several approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions have been developed in European health care system. Although most of these approaches have not been based on Wagner’s chronic care model explicitly, they can be analysed within a chronic care model framework. All approaches endeavour to improve self-management support for patients, develop clinical information systems and change the organization of health care – mostly by designing financial incentives. Changes in the delivery system design – e.g. be establishing division of labour between health professionals – and the development of decision support systems are less common. What is more, the link between health care services and community resources and policies is missing. Most importantly, the integration between the six components of the chronic care models remains an important challenge for the future. Implementation of new approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions is an important problem as well. Top-down approaches - national initiatives based on national regulation and national funding – have one important advantage: It is possible to implement new approaches to improve the management and coordination of chronic conditions rapidly and extensively. Bottom-up approaches – based on local and regional initiatives often struggle for sustainable funding but have a number of advantages as well: 16 They can be developed on a step-by-step basis and can be adapted to specific institutional, social and cultural circumstances. Moreover, by evaluating the process of implementation on a regular basis, it is possible to provide decision makers with rather hard evidence about the clinical and economic consequences of new model of providing health care for the chronically ill. Our analysis has shown that the predominant mode of financing – social health insurance vs. tax financing – does not seems to be a major factor for the development and implementation of new approaches to manage and coordinate chronic conditions. It can be argued that taxbased national health systems can use a more direct line of command to implement change in the organization of health care more easily. However, as the German case shows, the appropriate design of financial incentives for health insurers and health care providers can result in a wide-scale implementation on a national level as well. In contrast, the link towards implementation on a national level is still a challenge in national health systems such as Finland and Catalonia. However, we do find that the position of primary care in health care systems is an important factor for the development and implementation of new approaches to manage and coordinate chronic conditions. Our analysis supports the notion that countries with a strong primary care system tend to develop more comprehensive models to manage and coordinate chronic conditions. In contrast, countries with a weak primary care system are still struggling to develop these models or – as in Germany – neglect changes in the design of delivery systems, particularly in primary care. 17 7 References Advisory Council for the Concerted Action in Health Care. 2001. Appropriateness and Efficiency. Volume III: Overuse, underuse and misuse. http://www.svrgesundheit.de/Gutachten/Gutacht01/Kurzf-engl01.pdf: . Bodenheimer, T; Wagner, EH; Grumbach, K. 2002a. "Improving Primary Care for Patients With Chronic Illness". Jama 288 (14): 1775-1779. Bodenheimer, T; Wagner, EH; Grumbach, K. 2002b. "Improving Primary Care for Patients With Chronic Illness. The Chronic Care Model, Part 2". Jama 288 (15): 1909-1914. Busse, R. 2004. "Disease Management Programs In Germany’s Statutory Health Insurance System". Health Affairs 23 (3): 56-67. Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de gezondheidszorg. 2006. De kwaliteit en de organisatie van type 2 diabeteszorg. Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de gezondheidszorg, KCE reports vol.27 A: Brussels. Greß, S; Focke, A; Hessel, F; Wasem, J. 2006. "Financial incentives for disease management programmes and integrated care in German social health insurance". Health Policy 78 (2-3): 295-305. Macinko, J; Starfield, B; Shi, L. 2003. "The Contribution of Primary Care Systems to Health Outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Countries, 1970–1998". Health Services Research 38 (3): 831-65. Nolte, E; McKee, M. 2008a. Caring for people with chronic conditions: an introduction. In: Nolte, E; McKee, M. Caring for people with chronic conditions. A health system perspective, Open University Press: Berkshire, . Nolte, E; McKee, M. 2008b. Integration and chronic care: a review. In: Nolte, E; McKee, M. Caring for people with chronic conditions. A health system perspective, Open University Press: Berkshire, . Reisig, V; Wildner, M. 2008. Primary Prevention. In: Kirch, W. Encyclopedia of Public Health, Springer: Heidelberg, doi 10.1007/978-1-4020-5614-7_2759. Steuten, L; Vrijhoef, B; van Merode, F; Weeseling, G-J; Spreeuwenberg, C. 2006. "Evaluation of a regional disease management programme for patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". International Journal for Quality in Health Care 18 (6): 429-436. Steuten, LMG; Vrijhoef, HJM; Landewé-Cleuren, S; Schaper, N; Van Merode, GG; Spreeuwenberg, C. 2007. "A disease management programme for patients with diabetes mellitus is associated with improved quality of care within existing budgets". Diabetic Medicine 24 (1112-1120): . Stock, S; Redaelli, M; Lauterbach, KW. 2006. "Population-Based Disease Management in the German Statutory Health Insurance: Implementation and Preliminary Results". Disease Management & Health Outcomes 14 (1): 5-12. Stock, SAK; Redaelli, M; Lauterbach, KW. 2007. "Disease management and health care reforms in Germany-Does more competition lead to less solidarity?" Health Policy 80 (1): 86-96. Szecsenyi, J; Rosemann, T; Joos, S; Peters-Klimm, F; Miksch, A. 2008. "German diabetes disease management programs are appropriate to restructure care according to the Chronic Care Model. An evaluation with the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC-5A) instrument." Diabetes Care (Published online February 25, 2008): . Ullrich, W; Marschall, U; Graf, C. 2007. "Versorgungsmerkmale des Diabetes Mellitus in Disease Management Programmen". Diabetes, Stoffwechsel und Herz 16 (6): 407414. 18 Vrijhoef, HJM; Spreeuwenberg, C; Eijkelberg, IMJG; Wolffenbuttel, BHR; van Merode, GG. 2001. "Adoption of disease management model for diabetes in region of Maastricht". BMJ 323: 983-985. Wagner, EH; Austin, BT; Davis, C; Hindmarsh, M; Schaefer, J; Bonomi, A. 2001. "Improving Chronic Illness Care: Translating Evidence Into Action". Health Affairs 20 (6): 64-78. World Health Organization. 2003. Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions: Building Blocks for Action. World Health Organization http://www.who.int/diabetesactiononline/about/icccreport/en/index.html: Geneva. Zwar, N; Harris, M; Griffiths, R; Roland, M; Dennis, S; Powell Davies, G; Hasan, I. 2006. A Systematic Review of Chronic Disease Management. Australian Primary Health Care Institute: Sydney. 19