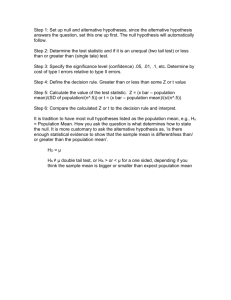

Solutions Manual for Fundamental Statistics for the Behavioral

advertisement