Micro-history of a House. Memory and Place on the Milanese

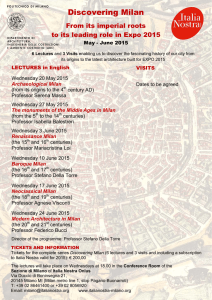

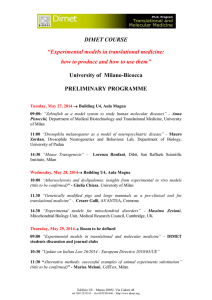

advertisement