Starting a study club

advertisement

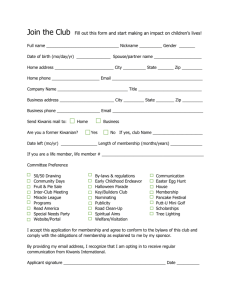

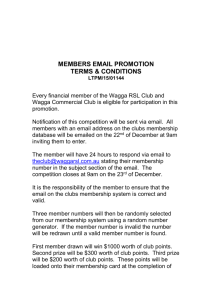

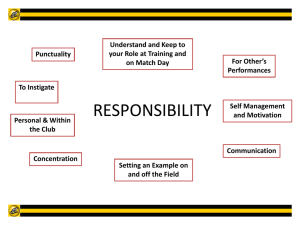

Thinking of starting a PLAB Study Club? There are already study clubs running in different ways in different parts of the country. So if you are thinking of setting up a study club, you don’t have to reinvent the wheel. You might want to visit one of the groups that already exists (contact Jo Constable at the BMA for a list). And you might like to read one or two tips and wrinkles that I wish someone had told me 2 years ago, when I first entered this field. What is a study club? Study clubs fulfil a number of different purposes for their members: Morale and social support by providing a regular meeting place for doctors facing similar problems An opportunity to meet British health professionals and learn about the NHS Study activities - group practise of PLAB questions and presentations to update medical knowledge - given by members themselves, the facilitator or outside speakers Books to borrow - IELTS books, medical textbooks, PLAB question books Access to PLAB 2 equipment Help with CV preparation and interview practise Assistance in finding clinical attachments References from a UK source Financial assistance for PLAB 2 fees, transport costs and some courses. What do we need to start one? Most clubs have a facilitator, who is usually (but not always) a British health care professional. The facilitator is needed because getting into work in the NHS requires more than simply studying clinical medicine. Club members will have lots of questions about the NHS, and there will also be lots of cultural issues (for example around consent, confidentiality and ethico-legal matters) that differ from country to country. Members need to learn about these differences, even though they are not directly tested in PLAB. Don’t underestimate the facilitation time that will be required. I found a two hour study club required a full day of my time, when preparation and one to one advice was taken into account. The club needs somewhere to meet regularly. A lending library of books is useful, and you will need PLAB 2 equipment to allow members to practise venepuncture, cannulation, catheterisation etc. You will need funding. Potential sources include the local primary care and hospital trusts - if they will not provide financial backing, they may offer rooms or library facilities; the strategic health authority - find out who is responsible for recruitment and retention of overseas trained medical personnel; and the department of health - you will have to bid for funding. Once you have had a bit of publicity you may find that other donors come forward - individuals, local Rotary clubs or church groups may offer help. You may also appreciate support in the form of volunteer time. Consider recruiting local medical students or drama students to act as patients for PLAB 2 practise. The medical defence unions can provide some interesting speakers on medico-legal matters. Tap in to the educational activities on offer from your local postgraduate medical deanery, local hospitals and primary care trusts. Seminars for general practitioners and their staff are often pitched at the right level for the PLAB candidates. These also offer an opportunity for the refugee doctors to meet British doctors, often in a social setting over a pre-lecture meal. If you choose to invite outside medical speakers to the club, you will need to prepare them in advance, so that they understand the group’s needs. A one hour talk on a consultant’s pet research topic is unlikely to be appropriate. By providing speakers beforehand with a few sample PLAB questions to use in their teaching session, you will help them to pitch it at the right level. And ask for feedback from club members as to which speakers were interesting and should be invited again. Should we start one mixed level club or several separate clubs? A mixed level group - with doctors studying for IELTS, PLAB 1, PLAB 2 and preparing for work - may not seem a logical mix, because of the difficulty of catering to the very different needs of the students. But, in fact, it can work quite well if the members are free to dip in and out as they feel appropriate. Those further on in their studies provide a useful source of advice and inspiration to those who are only just beginning. Even those with relatively little conversational English can often manage some PLAB 1 questions as medical English is easily recognisable, and this can give this group a morale boost. In a two hour club in Liverpool, we split the session between some PLAB 1 questions and some PLAB 2 practice stations - both on a theme that we had chosen the previous week. Everyone could prepare and join in and the club proved very popular. If you prefer to split the club into separate PLAB 1 and PLAB 2 groups, you need to be sure that you have enough students at each stage to make the session work. There is nothing so dispiriting as trying to run a club with only one member. If you don’t have enough members at an appropriate level for a PLAB 2 club, instead of trying to provide everything yourself, you might try and fund individual doctors to go on intensive courses that are available in London, Birmingham and Manchester. Those who have passed PLAB and are looking for clinical attachments or jobs must not be forgotten. They need as much if not more time, for help with CVs and interview preparation. Some of this will need to be on a one to one basis, so you need to take this into account in your planning. Should we include all overseas trained doctors? Whether or not to open up the club to all overseas doctors will depend on a number of factors, and there is no simple answer to this question: Including overseas doctors may be helpful if you have only a small number of asylum seekers and refugees locally, as there is a critical mass below which your club is unlikely to succeed. In addition, many overseas trained doctors have contacts in the UK and already have a good idea of what is needed to get into work in the NHS. This helps to fire up the whole group and a bit of healthy competition can encourage studying. However, some funding comes with restrictions and may dictate how you run the club. You could choose to charge a small membership fee to non-asylum seekers (for access to books and PLAB 2 equipment) to overcome this problem. An additional issue to consider is the ethics of encouraging overseas doctors - many of whom are from the developing world - to come and work in the UK. And don’t kid yourself, by providing help you are encouraging them. Also if you only have a restricted number of contacts to help provide clinical attachments, then you might want to limit these to asylum seekers and refugees only. Whatever your decision on this issue, be prepared to justify yourself as you are likely to be challenged at some point. How will potential members hear of the club? You will want to advertise the club through the local agencies working with asylum seekers and refugees - NASS housing providers, Refugee Action, ESOL and IELTS providers, local health care providers (many Primary Care Trusts now have special services for asylum seekers and refugees). Once you are up and running, local papers and local radio can be very helpful in advertising your existence through good news stories. In addition, word of mouth will soon increase the numbers coming to a successful club. Remember the principles of adult learning: Beware the old tradition within British medical education of “education by humiliation!” The club should provide a safe environment where students are allowed to make mistakes and learn from them. Students should be actively involved in deciding what it is that they want to learn. They should have the opportunity to prepare in advance of each session - if you are going to cover PLAB questions on cardiology next week, let members know, so that they can read around the subject and come with their questions for clarification. Working systematically through questions around a single theme is likely to be more productive than tackling random questions each session, and will encourage students to organise their thoughts. Students should be encouraged to develop good study habits, recognising their own limitations and learning where to find the information they need. The most worrying doctors are those who do not recognise when they don’t know something. I use textbooks in the club when I am uncertain, and encourage students to do the same. Finally - the club should be fun. If it isn’t fun, you aren’t doing it right! Consider having social activities from time to time - mixing refugee doctors with native English speakers for a meal, ten pin bowling or some other ‘cultural‘ activity. Produced by: Pip Fisher REACHE