`Religion` and the `new Irish`: a study in the use of Census data

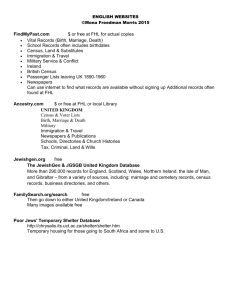

advertisement

Malcolm P.A. Macourt Honorary Research Fellow, Cathie Marsh Centre for Census and Survey Research, University of Manchester The ‘new religious landscape’ and the ‘new Irish’: the Census – a useful tool? To what extent can or should a Census of Population provide detailed evidence on an apparently new social phenomenon? In making Census data available to the public, where should the balance be struck between individual privacy and the need of society to have reliable evidence through which social policies may be addressed? Can a ‘new religious landscape’ be identified through Census data? In the context of ‘new religious movements’ this paper addresses both the censuses in the Republic of Ireland and in Northern Ireland, though its primary focus is on the Republic of Ireland. The Republic of Ireland’s population increased markedly in the decade from 1996. Much of that increase was through the inward migration of people with little or no prior connection with the state. Not only were there significant numbers of ‘new Irish’ (as the media called them) whose places of birth, nationality, or ethnic origin differ from the historical “Ireland, Irish and ‘White’” but also, in a hitherto almost mono-cultural state, “Catholic” appears no longer to be the only response to the religion question. Analysing the results of Census questions on religion and comparing those results with responses to questions on nationality, place of birth, ethnicity and length of stay in the Republic this paper explores how much it is possible to glean about ‘the new Irish’ and ‘new religious movements’ from the Census taken on Sunday 23rd April 2006. Data are taken from tables in published in Census Volumes and elsewhere by the Central Statistics Office (CSO), from its Small Area Population Statistics and from its Samples of Anonymised Records1. While it is possible to identify the nature and extent of changes to the religious landscape of the Republic of Ireland, it is only possible to provide limited detail on the arrival of religions longestablished elsewhere. The extent to which people classify themselves as non-religious or as consciously resisting religion can only be estimated from data which does not fully address these ways of being. Identifying the changing religious landscape of Northern Ireland from Census data is more difficult because (a) the most recent census was in April 20012, because (b) the different approach to the provision of data on the religions questions taken by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) and because (c) the ways in which British requirements on confidentiality have been interpreted makes detailed material difficult to assess. Nonetheless the extent of the province-wide provision of data on religions with small numbers of adherents provides some evidence of the changing religious landscape and offers some indication how new religious movements developed between 1991 and 2001. ________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction Both jurisdictions in the island of Ireland include questions on religion in their censuses. Civil disturbances for much of the period 1970-1995 in Northern Ireland and the, later, development of the ‘Celtic Tiger economy’ in the Republic of Ireland provide rather different contexts in which responses to the question have been given and data published. The population of the Republic of Ireland with inward investment, a buoyant labour market and inward migration increased by over 600,000 between 1996 and 2006. Net inward migration accounted for almost 60% of this increase3, fuelled partly by the widening of membership of the European Union from 15 to 25 members. This substantial immigration, with immigrants each bringing their own religious and cultural experience, make the Census results for 2002 and 2006 worth examining – particularly the results of the questions on religion, nationality, place of birth, length of stay and ethnicity for those religions with more than 10,000 adherents. [Sections 2-6] Little is published on religions with fewer responses, and many of those responses published have been grouped together. In Northern Ireland even less data on such responses from the religion questions in the 2001 Census is published, however the responses appear not to be grouped. Nonetheless the evidence on the religion questions is worth examining because it provides basic data on religions with few responses and because it provides evidence of the fragmentation of Protestantism. [Section 7] The benefits of examining ‘new religious movements’ through the results of the religion questions are not extensive, however some useful information can be discerned about religions long-established elsewhere. [Section 8] ________________________________________________________________ 2. Sources of census data (Republic of Ireland) on which this paper is based The 2002 and 2006 Census returns for the Republic relate to the de facto population and therefore much of the published material includes visitors present on census night as well as those in residence; usual residents temporarily absent from the area were excluded from the census count. The next census is scheduled for April 2011. For the 2006 Census one volume (No. 4) covered ‘Usual Residence, Migration, Birthplaces and Nationalities’, another (No. 5) covered ‘Ethnic or Cultural Background’; a further volume which covered ‘Religion’ (No. 13)4 was published in November 2007 as the last in the numbered list of volumes announced by the CSO. In a new departure, the CSO published in June 2008 ‘a thematic examination of the non-Irish national population’ which contained some additional evidence on religions longestablished elsewhere. Religion Religion has been a key feature of the development of the Republic of Ireland. A question on religion has featured in all decennial censuses since 1861. The question was worded: ‘State the religion, religious denomination or body to which the person belongs’, until 20025 when the wording changed to ‘what is your religion?’ In 2002 and 2006 respondents were asked to tick a ‘box’ – a new innovation in 2002 – one ‘box’ was provided each for Roman Catholic, Church of Ireland, Presbyterian, Methodist and Islam, and one for ‘Other, write in your RELIGION’. There was also a ‘box’ for ‘no religion’6. The numbers reported as belonging to what might be described as ‘new religious movements’ or to religions long-established elsewhere were not separately published until 1991 7, and then only national totals by gender for those religion labels recording more than 200 adherents 8. Deciphering the contents of ‘written in’ religions from the box ‘Other’, the CSO allocated some responses to the main religions – such as ‘Church of England’ to its fellow Anglican ‘Church of Ireland’ and created separate categories for others. These other categories included three catch-alls, ‘apostolic or pentecostal’, ‘evangelical’ and ‘pantheist’; other categories on which the CSO appears to have identified data but not published that data include Congregationalist, Seventh Day Adventist, Christian Scientist, Sikh, Unification Church (Moonies), Spiritualist, Satanist, Taoist and New Age. The CSO also identified particular sects within Islam (Shi’a, Sunni and Kharijite) and identified both Hare Krishna and Hindu, but did not publish results from these four. Separately from recording a category, the CSO published only those categories in which 200 or more people were identified. The CSO does not appear9 to have recorded Reformed Presbyterians, Free Presbyterians or Unitarians, each of which have several congregations in the Republic, neither did it record responses which indicated a particular groups of ‘evangelicals’, or of those of ‘pentecostal’ or ‘apostolic’ persuasion. The CSO programme of publication in 2002 and 2006 was extensive for those who responded in each of nine categories: the five ‘tick-boxed’ religions, two other religions [Orthodox and ‘Christian’ 10] which had over 10,000 adherents in the State, those who responded ‘none’ and those who made no statement. The level of detail for each of these nine categories, including those who ticked the ‘Islam’ box or who responded ‘Orthodox’ included total population, by gender, for each county and for each town with over 5,000 people. The CSO also published – but only for the whole Republic - a wide range of material including economic status, employment status, occupational group, socio-economic group and social class. It also included highest level of education completed and the age at which full-time education ceased. For those who were resident in private households it also included the nature of their occupancy. For males and females usually resident and present in the State, it included nationality. Beyond these nine categories, some individual religious denominations or religions had data published about them separately, others had none. Regional totals by gender were provided for each of sixteen religion responses11. Twelve of these responses were religions, denominations or groupings: ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’, Buddhist, Hindu, Lutheran, ‘Evangelical’, Jehovah’s Witness, Baptist, Jewish, Latter Day Saints (Mormon), Quaker (Society of Friends), Baha’i and Brethren; four responses referred to those who made a different sort of declaration: ‘Pantheist’, Agnostic, Atheist and ‘Lapsed Roman Catholic’. Exactly which of these categories should be included as ‘new religious movements’ and which as ‘New Age’ is clearly a matter for some debate; others can be described as ‘religions longestablished elsewhere’. It is extremely difficult to identify, from the Census question, those who classified themselves as consciously resisting religion (e.g. new spiritualities, humanism etc.). The choices offered to each of them seemed to be (a) tick the box relating to the religion in which they were brought up (e.g. Roman Catholic), (b) ignore the question altogether, (c) respond ‘none’, (d) respond with an answer which records their belief system (e.g. Agnostic). Basic data was published only for those responses, or groups of responses as decided by the CSO, which attracted 200 persons. ‘Place of Birth’, ‘Nationality’ and ‘Ethnic or Cultural Background’ Place of Birth questions have a long history in the Irish Census; in 2002 and 2006 the question invited as a response county of birth if on the island of Ireland, and country if outside Ireland. In 2006 612,629 people recorded that they were born outside the Republic, a significant increase from the 400,016 recorded in 2002, 271,177 in 1996 and 228,725 in 1991. Of those aged 25-39 in 2006, 24% were born outside the state; this compared with less 6% of those aged 70+12. The sole table contained in any of the published volumes which cross-classified place of birth and religion13 concerned only those persons usually resident and present in the State on census night; that table reported only on the nine ‘religion’ categories identified earlier. Over 63% of Muslims were born in Africa or Asia, and less than 24% were born in the Republic; just less than 57% of those identifying as Orthodox were born in European countries outside the (2006 boundaries) European Union and only 13% were born in the Republic. Just over 54% of those who responded ‘none’ were born in the Republic, compared with 82% of those who did not state a religion14. A question on nationality appeared in the Census for the first time in 2002. In 2006 multiple answers were permitted two of which were separately identified in the published material: Irish/English (14,512) and Irish/American (12,075). Apart from those who responded ‘Irish’, those who gave the single answer ‘British’ were – at 110,579 – the largest group in 2006 (an increase of less than 7% between 2002 and 2006); whereas those who gave a nationality other than Irish or British numbered 302,664, an increase of 77% in just four years. There was also one table which cross-classified nationality and religion15; it too concerned only those persons usually resident and present in the State on census night, and it too only reported on the nine ‘religion’ categories identified earlier. In 2006, with the arrival in the previous four years of many people of Polish and Lithuanian nationality (for example), over 95% of Roman Catholics had Irish or British nationality; for Church of Ireland almost 93%, over 80% for Presbyterians, almost 65% for ‘Christians’, and over 73% for those who responded ‘None’. Of those who did not state a religion and who did provide their nationality the equivalent datum was almost 78%, however over 43% of those who failed to state their nationality also failed to answer the question on religion. The question on ethnic or cultural background was introduced for the first time in 200616. Responses were encouraged in four main categories: ‘white’, ‘black’, ‘Asian’ and ‘other’. The category ‘white’ was sub-divided into Irish, Irish Traveller, and any other white background; ‘black’ into African and any other black background; ‘Asian’ into Chinese and any other Asian background; the ‘other’ category, which explicitly included those of ‘mixed background’ invited respondents to write in their own description17. Over 40,000 people failed to make a statement to both the religion and the ethnic questions. Almost 95% of the population stated that their ethnic or cultural background was ‘white’18; of the remainder, one-third made no statement and two thirds (3.43% of the population) gave ‘black’, Asian or ‘other’ responses. The percentage giving ‘black’, Asian or ‘other’ responses ranged from over 6% in Greater Dublin to less than 1% in rural areas and in villages with less than 1,500 inhabitants – with the percentage in some towns exceeding 8%. It is difficult to judge whether this question caused confusion to some respondents. For example although Roman Catholics constituted 49% of ‘other including mixed background’ ethnic origin 19, they constituted only 30% of black respondents and 26% of Asian respondents: this may be a reminder that some respondents might have considered themselves to be of ‘mixed background’ if they shared an Irish and an ‘other white’ origin. Of those who responded ‘Islam’, 1,886 gave a ‘white Irish’ response and 3,597 gave an ‘other white’ response – perhaps including those from Bosnia - together these responses accounted for over 1/6 th of all Muslims20. Usual Residence and Length of Stay Three questions were asked in the 2002 and 2006 Censuses on usual residence and length of stay; they covered (current) usual residence, usual residence one year before and a question for those who had lived outside the Republic for a year or more. Those only temporarily in the State can be identified by the country of their usual residence as can (separately) those who moved into the State in the twelve months before the Census. Those who had lived outside the Republic can be identified by the year of their (most recent) move into the State and by the country in which they last resided. The 2006 Census showed that there were 67,835 people temporarily in the State – presumably tourists and visiting business people for the most part - of them, 10,363 were born in Republic21. Of those residents who moved into the State in the twelve months before the 2006 Census (121,939), 98,391 had been born outside the Republic 22. ________________________________________________________________ 3. Small Area Population Statistics (SAPS) The Small Area Population Statistics (SAPS) made available following the 2006 Census contain over 1000 items of census information about each District Electoral Division (DED) and, for the five cities and their suburbs, about each Enumeration Area23. Most questions in the Census are represented, and the extent of data is marked. However on the questions which form the concern of this paper the evidence ranges from that which is directly relevant to that which is only marginally useful. Religion has appeared in the SAPS since 1981, albeit only minimally. In 2002 and 2006 only eight pieces of evidence are available for each DED: for both genders, totals for Roman Catholic, All Other Stated Religions, ‘none’, and ‘not stated’. Place of Birth and Nationality are included in the SAPS. However for each, persons usually resident in the State are divided into seven categories: Republic of Ireland, UK, Poland, Lithuania, other EU countries/nationalities, rest of the world and not stated. Poland and Lithuania were included in the 2006 SAPS for the first time. Ethnicity has been included in the 2006 SAPS, however the only categories included were: Irish Traveller, Black Irish, Asian Irish, Other and Not Stated. The location of recent migrants in individual DEDs – the ‘New Irish’ – may be deduced with difficulty by examining the Place of Birth, Nationality, Ethnicity and the All Other Stated Religions material. Without further categories for three variables in the SAPS (religion, place of birth, nationality) little can be deduced at the small scale. Without separating (for example) USA, Australia and Nigeria from other places of birth or nationality, without separating the traditional Irish protestant churches from others, little can be achieved in identifying the extent and nature of ‘new religions’ in individual parts of the Republic. While the inclusion of Enumeration Areas in and surrounding the five cities has made it much easier to locate particular communities of some of the ‘New Irish’ using Census data alone, there is no direct benefit for locating ‘new religions’. _____________________________________________________________ 4. Samples of Anonymised Records The decision by the CSO to make available a Sample of Anonymised Records (SAR) 24 was a crucial one for census analysts, though the benefits of such samples are very limited when studying ‘new religions’. The CSO first made a SAR available after the 1996 Census; this was followed by a 5% SAR after the 2002 Census – in which there was a religion question – and again after a similar Census in 2006. As the official Guide to the 2002 5% SAR has it: ‘The records relating to persons within households were anonymised by striping off all identifiable information such as household number, person number within household and by recoding variables where the number of categories could lead to the identification of an individual when combined with other information on the record.’ The Guides list the variables included and their categories. While the lowest level of geography given is the County, persons in the sample are also coded by whether they were enumerated in an Urban Area (which includes towns and cities with a population of 1,500 persons or more) or in a Rural Area. The decision to include religion as one of the 29 variables in the 5% SARs for both the 2002 and 2006 was an important one; however the decision only to recognise ‘Church of Ireland’ in addition to Roman Catholic, ‘none’, and ‘not stated’ has severely limited the use of SARs in the context of this paper. The 5% SARs also include Place of Birth, Nationality, ‘Usual Residence one year ago’, Year taking up residency in Ireland and Country of Previous Residence – and for 2006 Ethnicity. However, for the purposes of these samples, place of birth for those born outside the Republic of Ireland, and country of previous residence for those who had lived outside the Republic ‘for a period of a year or more’, were grouped into 5 headings: Northern Ireland, Great Britain, Other EU, USA and ‘Other countries’. The only ‘nationalities’ identified in the 5% SARs were Irish, Non-Irish and Not Stated25, the only ‘ethnicities’ identified were Irish (including Irish Traveller), ‘other stated ethnicity’ and not stated. For ‘usual residence one year ago’, only two categories outside the Republic were identified: in Northern Ireland and elsewhere (abroad). Those who lived outside the Republic for a period of one year or more were asked to indicate the year of taking up residence in the Republic, the year stated was grouped into 7 decennial categories including (for 2006) 1991-2000 and 2001-2006. ________________________________________________________________ 5. Data from the 2006 Census: published Census Reports, SAPS, SARs In the first Census taken after the creation of two jurisdictions in Ireland (taken in 1926) 92½% of the population of the Irish Free State claimed to belong to the Roman Catholic Church; that church was accorded special status in the Constitution of the Republic of Ireland in 1937, and for many had extensive influence. By 1961 the percentage of Roman Catholics had increased to over 95%, and less than ¼% failed to claim a religion: less than 140,000 of those who did claim a religion claimed one other than the Roman Catholic Church26. This number only increased by 10,000 in the 30 years to 1991, while in that census a further 150,000 failed to claim a religion. By 2006 the numbers claiming a religion other than Roman Catholic had doubled to just over 300,000, with over 250,000 failing to claim a religion. The 1991 Census Report showed that, of those who claimed a religion, 95% claimed the Roman Catholic Church as their church – the same as 30 years earlier. In 1991 almost 2% of the total population claimed that they had no religion, and a further 2½% made no statement. By 2006 rather more than double the 1991 percentage – nearly 4½% - claimed that they had no religion; the numbers who failed to make a statement had slowly reduced since 1991, from over 83,000 to 70,000 in 2006. By 2006 of those who did claim a religion, the percentage claiming to be Roman Catholic had reduced slightly to 92½%. Table 1 demonstrates that the number of those who did not declare a religion has increased from just over 150,000 in 1991 to over 250,000 in 2006. How people classify themselves as non-religious or as consciously resisting religion can only be estimated from data which does not fully address these ways of being. Table 1: major responses to the 2006 4,239,848 Republic of Ireland 257,180 Absence of religion 3,681,446 Roman Catholic 121,229 Church of Ireland27 179,993 ‘Other Stated Religions’ religion % 100.0 6.07 86.8 2.86 4.25 question, 1991, 2002, 2006 with gender ratios f/m06 2002 % f/m02 1991 % 1.00 3,917,203 100.0 1.01 3,525,719 100.0 0.71 5.56 0.76 4.35 217,948 153,394 1.02 1.03 3,462,606 88.4 3,228,327 91.6 1.02 2.87 1.02 2.35 112,507 82,840 0.95 3.17 0.93 1.73 124,142 61,158 f/m91 1.01 0.78 1.02 1.04 0.98 Of which: the 5 largest: and all the rest 118,249 61,744 81,602 42,540 38,798 22,360 Table 2 demonstrates how the balance between the three ‘responses’ included in this ‘absence of religion’ grouping has changed in 15 years, by 2006 explicitly declaring that they have no religion has almost tripled from 66,270 to 186,318. Table 2: disaggregation of ‘absence of religion’, 1991, 2002, 2006, with gender ratios 2006 % f/m06 2002 % f/m02 1991 % f/m91 0.71 217,948 5.56 0.76 153,394 4.35 0.78 Absence of religion 257,180 6.07 None 0.68 138,264 3.53 0.68 66,270 1.88 0.65 186,318 4.39 No Statement 0.79 79,094 2.02 0.92 83,375 2.36 0.90 70,322 1.66 ‘Lapsed RC’ 1.27 590 0.02 1.06 3,749 0.11 0.90 540 0.01 Among those who responded ‘none’ and those who made no statement men significantly outnumbered women. Compared with the population at large, there are less than 70% of the number of women who responded ‘none’ and less than 80% of the number of women who made no statement. Of 67,835 tourists and visitors, 11,066 (16.3%) responded ‘none’ to the religion question and a further 3,572 (5.3%) made no statement; in each case these were less skewed toward males than the resident population28. Less detail was published on Islam, ‘Christian’, Presbyterian, Orthodox and Methodist than for the five major categories given in Table 1, however – as outlined in section 2 above – rather more is published about them than about responses with fewer respondents. Table 3 notes that three-quarters of Muslims and Orthodox were born outside the Republic and the United Kingdom but less than 40% of ‘Christians’, Methodists and Presbyterians. In 2006 Methodists and Presbyterians contain higher percentages of non-residents than do the other three. Table 3: 5 largest ‘other’ religious statements, with non-residents, gender ratios and birthplace29 2006 f/m06 % NR % born 2002 f/m02 % NR % born 1991 f/m91 the 5 largest 118,249 81,602 38,798 32,539 0.68 0.63 0.61 Islam 2.3 74.3 19,147 6.1 75.8 3,875 29,206 1.12 1.12 1.02 ‘Christian’ 4.0 37.2 21,403 4.9 26.4 16,329 23,546 0.96 0.96 0.97 Presbyterian 8.7 20.7 20,582 9.8 13.3 13,199 20,798 0.95 0.84 0.58 Orthodox 3.9 86.2 10,437 12.3 87.8 358 12,160 1.01 1.00 1.09 Methodist 11.4 35.5 10,033 12.3 27.5 5,037 Table 3 also gives gender ratios: these demonstrate that males predominate among Muslims – there were less than 70% of the number of females expected, perhaps because many male Muslims had made the journey from Africa and Asia to Ireland and had settled before inviting female Muslims to join them. The gender imbalance among Orthodox is rather less (at 95%) than in the two previous censuses. Given that a large part of the Presbyterian population is involved in agriculture the slight gender balance is not unexpected. Among those who responded ‘Christian’, however, there is more than a 10% excess of females: a similar ratio to ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’, ‘Evangelical’ and Baptist, as may be seen in Table 4 where the national totals are given for 16 responses. Even greater gender imbalances may be found among Lutherans, ‘Protestants’ and Jehovah’s Witnesses. Gender imbalances in the other direction is found among Hindus – perhaps for reasons similar to those for Muslims – and among Agnostics and Atheists though, perhaps surprisingly, not among ‘Pantheists’. Comparing the wider area around Dublin with the rest of the Republic is instructive. As can be seen in Table 5, for most statements a much larger proportion lived in this wider Dublin area than in the rest of the Republic. The counties of Dublin, Wicklow, Meath and Kildare – which encompass the city, its suburbs and its wider commuter area – comprised just less than 40% of the population of the state in 2006. For those who gave responses coded as Islam, Orthodox, ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’, Buddhist, Hindu and Jewish the proportions are more than double – and for those who responded ‘Christian’, Lutheran, ‘Evangelical’ and ‘Protestant’ not much less. Exceptions to this are the Presbyterians (comparatively strong in the Border counties), Jehovah’s Witnesses, ‘Pantheists’ and Baha’is. Table 4: other responses to the religion 2006 Religious statement % 61,744 Total: ‘the remainder’ 8,116 ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’ 0.19 6,516 Buddhist 0.15 6,082 Hindu 0.14 5,279 Lutheran 0.12 5,276 ‘Evangelical’ 0.12 5,152 Jehovah’s Witness 0.12 4,356 ‘Protestant’ 0.10 3,338 Baptist 0.08 1,930 Jewish <0.05 1,691 ‘Pantheist’ 1,515 Agnostic 1,237 Mormon 929 Atheist 882 Quaker 504 Baha’i 365 Brethren Other Stated Religions 8,576 question30, 1991, 2002, 2006, f/m06 2002 f/m02 1991 42,540 22,360 1.13 1.14 3,152 285 1.08 0.90 3,894 986 0.64 0.57 3,099 953 1.54 1.64 3,068 1,010 1.16 1.20 3,780 819 1.24 1.18 4,430 3,393 1.31 1.34 3,104 6,347 1.17 1.07 2,265 1,156 0.92 0.96 1,790 1,581 1.11 1.12 1,106 202 0.56 0.64 1,028 823 1.05 0.95 833 853 0.45 0.40 500 320 1.13 1.08 859 749 0.96 0.98 490 430 0.98 0.82 222 256 0.74 8,920 0.82 2,197 with gender ratios f/m91 1.16 0.75 0.67 1.40 1.13 1.21 1.09 1.13 1.02 0.66 0.64 1.11 0.39 1.15 0.98 1.27 0.89 Table 5: Religion for Dublin and Mid-East (DME) Regions31 & for remainder of Republic (Rem): 2002 & 2006 Religion DME: 2006 DME: 2002 % 06 Rem: 2006 Rem: 2002 % 06 19,323 11,314 1.16 Islam 13,216 7,833 0.51 0.92 ‘Christian’ 15,327 10,773 13,879 10,630 0.54 15,036 13,506 0.58 Presbyterian 8,510 7,076 0.51 0.80 Orthodox 13,297 6,842 7,501 3,595 0.29 Methodist 5,580 4,583 0.34 6,580 5,450 0.26 0.29 ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’ 4,741 1,672 3,375 1,480 0.13 0.23 Buddhist 3,809 2,203 2,707 1,691 0.11 0.25 Hindu 4,131 1,941 1,951 1,168 0.08 0.16 Lutheran 2,681 1,623 2,598 1,476 0.10 0.16 ‘Evangelical’ 2,686 2,464 2,590 1,316 0.10 0.14 Jehovah’s Witness 1,606 1,317 0.10 3,546 3,313 0.14 ‘Protestant’32 2,404 * 1,952 * 0.08 Baptist 1,646 1,081 0.10 1,692 1,184 0.07 0.08 Jewish 1,368 1,336 562 454 0.02 ‘Pantheist’ 701 479 0.04 990 627 0.04 Agnostic 851 589 0.05 664 439 0.02 Mormon 677 491 0.05 570 342 0.02 Atheist 518 300 0.03 411 200 0.02 Quaker 494 491 0.03 388 368 0.02 ‘Lapsed RC’ 299 333 0.02 241 257 <0.01 0.01 Baha’i 163 159 <0.01 341 331 Brethren 214 106 0.01 151 116 <0.01 Other stated religions 4,546 4,292 0.27 4,030 4,628 0.16 None 100,133 76,296 6.02 86,185 61,968 3.34 Not Stated 35,264 40,029 2.12 35,058 39,065 1.36 Total 1,662,536 1,535,446 2,577,312 2,381,757 ________________________________________________________________ 6. The Thematic Examination ‘Non-Irish Nationals living in Ireland’ The CSO broke new ground in June 2008 in publishing the thematic examination ‘Non-Irish Nationals living in Ireland’ based on the 2006 census. It identified material which would be of particular interest to the public and published its selection of that material separately. Unlike the Census Volumes this thematic examination dealt (for the most part) only with those who were resident in Ireland at the time – non-residents were excluded from the analysis. The thematic examination stressed the heterogeneity of the non-national population by identifying the ten nationalities which figured most frequently in the census and contrasting various indicators relating to each group. So, for example, age pyramids demonstrated both that all of non-Irish national population taken together contained a dramatically higher percentage of people in their 20s and 30s than the Irish national population and that those of one nationality (the British) had characteristics which ‘tend[ed] to be similar to those of the Irish population’. The authors of the thematic examination were content to make general statements about some of the nationalities identified: ‘For example, while the Polish are largely here to work, the Chinese are here to study; the UK nationals live mainly in rural areas while the Nigerians are highly urbanised; the US nationals are concentrated in the higher social classes while those from accession states 33 tend to be working in the manual skilled areas.’ Much of the material published in the thematic examination was new to the public; some of it had been published in the Census Volumes but in a form which made it difficult to identify. For some ‘migrant workers’ faced with a census form – particularly those without current employment – deciding whether to describe themselves as resident or simply as visitors to the Republic may have provided a particular challenge. The thematic examination fails to address this question. The thematic examination does contain a single table of data which relates to the focus of this paper. For each of the ten nationalities identified, in addition to Roman Catholic, Church of Ireland, ‘none’ and ‘not stated’ the table provides data on those residents who described themselves as ‘Christian’, Presbyterian, Methodist, Islam, ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’, Orthodox, Lutheran, Jehovah’s Witness, ‘Protestant’, Buddhist, ‘Evangelical’, Baptist, Jewish, and ‘Pantheist’. Table 6, like the table in the thematic examination from which it is abstracted, does not include data on Hindu, Mormon, Quaker, Baha’i, Brethren, Agnostic, Atheist or ‘Lapsed Roman Catholic’. Table 6: 2006 Persons resident by religion for nine selected nationalities 34 Nationalities Chinese The % 9 Polish Lithuanian Nigerian Latvian American of (USA) nine German Filipino French total ‘Christian’ Church of Ireland ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’ Orthodox Islam Lutheran Presbyterian Methodist ‘Protestant’ Buddhist ‘Evangelical’ Baptist Jehovah’s Witness Jewish ‘Pantheist’ 4,988 3,132 18 3 174 258 361 547 2,757 1,237 217 90 427 324 202 226 155 374 634 34 61 42 3,084 39 27 12 2,886 17 49 0 30 57 6 2,758 2,697 2,600 1,446 1,352 1,228 896 841 701 561 14 8 50 7 13 31 14 16 21 11 62 91 19 30 23 78 68 37 36 184 787 45 23 41 26 31 9 28 18 31 2 1,990 1 718 806 167 0 280 217 108 1,808 46 1,443 130 28 44 4 6 35 10 34 69 136 216 227 43 49 147 249 33 0 53 1 57 55 5 673 10 3 6 31 94 972 209 48 782 48 270 16 61 3 69 0 21 134 43 3 47 121 74 31 240 5 24 5 35 42 16 6 54 183 120 10 7 17 17 6 11 0 8 0 6 107 45 2 4 18 23 1 0 32 6 Other No religion Not stated 1,962 24,998 5,694 16 14 9 195 2,961 1,284 197 1,304 855 253 119 756 423 3,516 719 307 1,644 653 267 8,399 660 117 3,687 325 115 23 112 88 3,345 330 Table 6 demonstrates that, among some minority religions, being a national of one of these nine nations was very important, whereas for others it was not. A very significant proportion of all Lutherans, of those recorded as ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’ and of those responding ‘Protestant’ is found among these nine nationalities. Persons recorded as ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’ and persons claiming (simply) to be ‘Christian’ dominate non-Catholic Nigerians, Orthodox and Lutheran dominate Latvians, and Lutherans and ‘Protestants’ dominate non-Catholic Germans. Whereas Buddhists constitute the largest group among the Chinese, they form well under 10% of all Chinese. Other references to religions in the thematic examination concerned the ten next-largest nationalities resident in the State in 2006. These one-line references to religious statements other than to Roman Catholic, were: ‘40 per cent [of the 8,329 Indians] identified [as] Hindu’ ‘Orthodox was the main religion [of the 7,696 Romanians] (55%)’ ‘A high 58 per cent [of the 5,110 Czechs] indicated they had no religion, by far the highest for any of the eastern European countries’ ‘[The 4,926 Pakistanis] were 97 per cent Muslim, by far the highest single religion of any of the groups profiled’ ‘Their [the 4,426 Russians] main religion was Orthodox.’ _____________________________________________________________ 7. Northern Ireland The only census in Northern Ireland since April 1991 was that held in April 2001. As in the Republic, the next census is due in April 2011. Unlike for the Republic, for both the 1991 and 2001 censuses, data was published for the usually resident population only. Questions on nationality and length of stay did not figure in the 2001 Census; however questions on country of birth and ethnicity were included, although available material linking either question to religion is limited. Just as in the Republic, there has been a question on religion in each decennial census since the jurisdiction was founded. However the two censuses have taken different directions since April 1991. Then both censuses included the invitation to ‘state the religion, religious denomination or body to which the person belongs’. In 2001 government need for ‘base-line’ data to monitor the impact of equality legislation lead to replacing the single ‘religion’ question with three questions designed to identify which ‘community’ (catholic or protestant) identified themselves. The first question was: Do you regard yourself as belonging to any particular religion? Those who answered ‘yes’ were directed to What religion, religious denomination or body do you belong to? This question had five boxes, one each for the four major denominations35 and one for ‘Other, please write in’. Those who answered no were directed to: What religion, religious denomination or body were you brought up in? The five boxes were repeated, and a sixth one added: None. This third question, the ‘community background’ question, is the focus of much of the publication programme of the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA). In addition to data published on the four major denominations in Northern Ireland (Roman Catholic, Presbyterian, Church of Ireland and Methodist), some data was published about three general categories: ‘Other Christian (including Christian related)’, ‘other religions and philosophies’ and ‘no religion or religion not stated’. Table 7 contains a summary of those three general categories, with comparative data for 1991. In 2001 97½% of those in ‘no religion or religion not stated’ were described as ‘white’ and 4¼% were born outside UK and Ireland. Table 7: responses to the religion question, 1991 & 2001 with gender ratios f/m01 1991 f/m91 Northern Ireland 2001 1.05 1,577,836 1.05 All persons 1,685,267 1.10 Other Christian (including Christian related) 102,221 0.79 Other religions and philosophies 5,028 0.85 0.91 No religion or religion not stated 233,853 176,434 0.78 None 59,234 1.01 Not Stated 114,827 0.90 Indefinite answer 2,373 NISRA appears to have taken a different view of the component parts of ‘other Christian (including Christian related)’ and ‘other religions and philosophies’ to that taken by the CSO. Rather than create general catch-all categories such as ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’, ‘Evangelical’ and ‘Pantheist’, NISRA published a single ‘Standard Table’36 which recorded gender totals for Northern Ireland as a whole for those labels with ten or more adherents. Consequently the difficulties in comparing results from the two jurisdictions are considerable. Tables 8 identifies those ‘other Christian (including Christian related)’ groups with more than 400 adherents37, with results for 1991 and with calculated gender ratios. Over 99% of the people in this category were described as ‘white’, 3% were born outside UK and Ireland. Table 8: ‘other Christian (including Christian related)’ 1991 and 2001, with gender ratios 38 f/m Religion39 2001 1991 Baptist 18,974 19,484 1.14 Free Presbyterian 11,989 12,363 1.02 Brethren 8,685 14,446 1.21 ‘Christian’ 8,502 10,556 1.04 1.22 Elim 5,972 5,537 1.18 Congregationalist 5,701 8,176 1.23 Pentecostal 5,533 4,312 ‘Protestant’ 4,299 12,386 1.00 1.06 Reformed Presbyterian 2,330 3,184 1.29 Jehovah’s Witness 1,993 2,121 1.15 Independent Methodist 1,771 835 1.33 Salvation Army 1,640 1,918 1.08 Non-Subscribing Presbyterian 1,575 3,365 1.23 Mormon 1,414 1,437 1.19 Evangelical 1,266 623 1.21 Christian Fellowship Church 1,215 1,300 1.28 Church of the Nazarene 1,215 1,149 1.17 ‘Non Denominational’ 1,115 1,401 1.18 Church of God 990 1,910 1.22 Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) 749 804 1.17 Moravian 691 714 1.21 Evangelical Presbyterian 543 730 Many of the groups in Table 8 are long-established denominations in Northern Ireland. Some labels however cause confusion, for example ‘Protestant’ or ‘Non-denominational’ may indicate a connection with a congregation which relates to more than one of the major Protestant churches or it may simply describe a ‘tribal’ attachment to Protestantism; ‘Christian’ may either indicate connection with a congregation organised around evangelical or pentecostal principles or it may describe a loose religious attachment to Christianity. The gender ratios of the six denominations with the highest ratio all exceed 1.22 – against a Northern Ireland ratio of 1.05. Five of these six denominations (Elim, Pentecostal, Mormon, Church of the Nazarene and Jehovah’s Witness) owe their origin and numerical strength outside the United Kingdom and Ireland. On the other hand the three denominations with the lowest gender ratios are denominations with their origins in religious disputes within Northern Ireland (Free Presbyterian, Reformed Presbyterian and Non-Subscribing Presbyterian); the other two labels with low gender ratios are ‘Protestant’ and ‘Christian’. Over 40 other labels were classified by NISRA as being ‘other Christian (including Christian related)’. Many of these have a long history in Northern Ireland, however two (Orthodox and Lutheran) are major strands of world Christianity, two more (‘Independent’ and ‘Interdenominational’) may indicate a lack of involvement in any denomination or religion or may indicate (as may two others - Independent Evangelist and ‘Charismatic’) connection with a congregation organised around evangelical or Pentecostal principles. In Table 9 (a, b & c) those groups classified by NISRA as being ‘Other religions and philosophies’ are identified. Of the 5,028 people concerned, 1,937 were described as ‘white’ and 1,894 as ‘Asian’; 1,919 were born in Northern Ireland and 2,431 outside UK and Ireland. The six largest are well-known world religions, all with over 200 adherents in Northern Ireland. Table 9a ‘Other religions and Religion 2001 1991 Muslim (Islam) 1,943 972 Hindu 825 742 Buddhist 533 270 Jewish 365 410 Baha'i 254 319 Sikh 219 157 Zoroastrian 11 10 philosophies’: religions long-established elsewhere f/m 0.67 0.88 0.74 0.99 1.11 0.92 Large gender imbalances are evident among Muslim and Buddhist, but imbalances are less evident among Hindu and Sikh. These imbalances may, in part, be because of the length of time that a particular community has been established. Four labels indicating those who were non-religious or consciously resisting religion were used by rather fewer people in 2001 than in 1991, Agnostic (742 to 66), Atheist (470 to 106), Humanist 69 to 40 and Free Thinker (56 to less than 10); collectively these labels were used by 56 women for every 100 men. This reduction in numbers may be related to the appearance in 2001 of a box which respondents could tick, labelled ‘none’. Table 9b ‘Other religions and philosophies’: non-religious or consciously resisting religion? Religion 2001 1991 Atheist 106 470 Agnostic 66 742 Free Thinker [<10] 56 Humanist 40 69 Five other labels (Pagan, ‘own belief system’, Wicca, Druidism, Satanism) appeared in the list of published religions for the first time, with a total of 295 respondents; four other religions also appeared for the first time: Hare Krishna, Taoist, Chinese Religions and Rastafarian, with 137 respondents. Spiritualist, a label used for many decades, was used by only 106 people in 2001, compared with 146 in 1991. Of all these labels, perhaps unsurprisingly, Wicca had a rather different gender profile. Table 9c ‘Other religions and philosophies’: new ways of being? Religion 2001 Pagan 148 Spiritualist 106 Own Belief System 65 Hare Krishna 53 Wicca 50 Taoist 41 Chinese Religions 32 Druidism 19 Satanism 13 Rastafarian 11 There are no tables which relate any detail in ‘other Christian (including Christian related)’ and ‘other religions and philosophies’ to any other census responses – whether geography, age, country of birth or ethnicity. This serious limitation (at least) avoids NISRA interpretation of British requirements on confidentiality which, in other contexts, have made detailed material difficult to assess. _____________________________________________________________ 8. Discussion The boundaries between ‘facts’, ‘beliefs’ and ‘opinions’ cause serious problems for every census office. In the first Census in Ireland to include a question on religion – 150 years ago – it was clear that the Irish appeared to know their ‘religious profession’ (as the question was phrased), they regarded it as a factual question requiring no interpretation and each had an answer which could be declared openly to a census enumerator. However by the new millennium the issue of what respondents meant when they answered a question on religion had become a live one. An individual respondent is faced with whether to tick the box of the relevant denomination when their only connection is that their grandparent, when alive, put in an attendance once each year around Christmas. Are they giving a ‘cultural’ answer – identifying with, say, ‘Church of Ireland’ rather than, say, ‘Presbyterian’ or ‘Roman Catholic’ – because they identify, however loosely, with that church but do not believe in – or even know about - any of its basic tenets? How do those persons who have some involvement with a ‘new religious movement’ or who have a new way of being respond to the religion question? Should that involvement become their response? ‘Yes’ may be too simple an answer in island with a long history of religious and ‘tribal’ identification. Furthermore if those persons classify themselves as non-religious or as consciously resisting religion their responses (ticking the box ‘none’) cannot be distinguished from those who simply do not have a religion and who also tick that box. With some difficulty religions long-established elsewhere can be recorded and the results made available. Responses such as Islam and Hindu can be reported – though whether they are adequately reported in either jurisdiction is open to question. Only in the 2001 Census for Northern Ireland, with its lower limit for publication of 10 adherents for that jurisdistion, were there found explicit examples of ‘new religious movements’ or ways of being. Pagan, Wicca, Druidism and Satanism may have only been labels used by 230 people but the label given to their equivalent in the Republic, Pantheist, does not express the flavour of diversity so well. The different approach used in the Republic – of grouping responses into wider categories – has affected the appearance of the results. This different approach has also affected those elements of Christianity which are described as ‘Apostolic or Pentecostal’ or as ‘Evangelical’. Both of these general responses were used by over 5,000 people in 2006. For some respondents such responses reflect long-established denominations in – for example – Nigeria, for some others the same response reflects a religion acquired in the Republic, for most (perhaps) the grouping is a statistical artefact. Without agreement between the two census offices (CSO and NISRA) direct cross-jurisdiction comparison is not possible. Nonetheless the Census of Population remains an immensely useful tool. In both jurisdictions considerable resources are put into ensuring that information is made available in forms accessible to the general population. New issues for questions are considered carefully, and where thought to be appropriate, are tested in informal and formal exercises, not least in the CSO Census Pilot Survey undertaken on 19th April 2009 for the 2011 Census. The Census remains the most reliable exercise for providing self-reported evidence on the social condition of the population, however unless the publication programme is explicitly set up to reveal such data, a census does not yield detailed useful information on ‘new religious movements’ or ways of being. Malcolm Macourt # macourtmpa@aol.com 1 This paper does not review other sources of evidence about ‘new religions’ or about the ‘new Irish’. Its predecessor was held in April 1991. 3 Data taken from 2006 Census Volume 4 Table 1 4 Volumes 4 and 5 were published in July 2007, and Volume 13 in November 2007. 5 The Census was postponed from April 2001 because of fears of Foot and Mouth Disease. 6 The CSO’s ‘Detailed Look at Census Questions’ (on the CSO website) for the 2006 Census reminded readers that the question made no assumptions concerning the basis of judgements made by individuals: it included that it was ‘important to point out that the question does not refer to frequency of attendance at church’. 7 Except that, as in previous censuses, in 1981 national totals were given for ‘Lutheran’, ‘Society of Friends’ and ‘Baptist’, alongside details for Church of Ireland, limited details for Presbyterian and Methodist, and county totals (only) for ‘Jewish’. 8 In 1991 these were: ‘Christian (unspecified)’ (16,329), ‘Protestant’ (6,347) ‘Muslim (Islamic)’ (3,875), ‘Lapsed Roman Catholic’ (3,749), ‘Jehovah’s Witness’ (3,393), and fifteen others recording more than 200 but less than 1,600. 9 From the ‘final list’ of responses, 2004, CSO. 2 10 ‘Christian’ appears to be those who wrote in that (precise) response. However in one instance it appears that ‘Christian’ is used to describe all those who entered a response which the CSO regarded as Christian but which was not covered by any other response in the relevant list of responses. As O’Leary has it: ‘Describing oneself as “Christian” could refer to membership of one of the very small congregations organised around evangelical or Pentecostal Protestant churches. On the other hand, it may be being used to describe a loose religious attachment to Christianity, perhaps by persons who by origin were affiliated to the main Christian denominations but who have lapsed in their church attendance’ Richard O’Leary: ‘Change in the Rate and Pattern of Religious Intermarriage in the Republic of Ireland’ The Economic and Social Review, Vol. 30, No. 2, April, 1999, pp. 119-132. 11 As described later, ‘Protestant’ was separately identified in the thematic volume ‘Non-Irish nationals living in Ireland’; as indicated earlier county totals continued to be given for ‘Jewish’. 12 4¾% of those aged 25-39 were born in Africa or Asia as were ¼% of those aged 70+. 13 Table 15 Vol. 13, 2006 and Table 14 Vol. 12, 2002 14 In 2006 just under 90% of Roman Catholics were born in the Republic as were 69% of the Church of Ireland, 54% of ‘Christians’ and 55% of Presbyterians. It appears that a place of birth was obtained from all respondents. 15 Table 16 Vol. 13, 2006 and Table 15 Vol. 12, 2002 16 ‘…coupled with information from other questions on the form, the responses [to the ethnicity question] will facilitate a comparison of the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the different ethnic and cultural groups living in Ireland’ from ‘Detailed look at census questions’ op. cit. 17 It appears that those who regarded themselves as being (for example) of both White Irish and White British ‘ethnic’ origins were permitted to record themselves as being of ‘mixed’ origin. 18 However see the previous footnote. 19 Table 7 Vol. 5, 2006 concerned only those persons usually resident and present in the State on census night, and it only reported on nine ‘religion’ categories identified earlier. 20 If it were possible to establish the ages of ‘white Irish’ Muslims from the published material some measure of the extent of any confusion over the question could be established. 21 58,708 people temporarily in the State in 2002 of whom 10,245 were born in the Republic; in 1996 29,544 and 9,991; and 1991 23,315 and 8,744. 22 Table 9 Volume 4. 50,525 in 2002. 23,548 people born in the Republic moved back in the twelve months before the 2006 Census, 25,579 before 2002. 23 An Enumeration Area is ‘the area assigned to each enumerator for the purpose of census enumeration. It is a logical contiguous area of a manageable size and usually contains about 350 dwellings’. District Electoral Divisions (DEDs) have been known as Electoral Divisions since 1996. Where data contained for each DED is mentioned it may be assumed that this applies also to Enumeration Areas in and surrounding cities. 24 A copy of the SARs datasets has been lodged with the Irish Social Science Data Archive (ISSDA). ISSDA may authorise users who are bona fide students, staff or research personnel to have access to the data for the purposes of economic and social research. Use of the data and/or any results obtained from use of the data for any other purposes is prohibited without the express permission of the CSO. Further details of each SAR is available the SAR User Guide for each census, each available on the Central Statistics Office website www.cso.ie/census/default.htm 25 Those who had ‘joint Irish and another nationality’ were identified as Irish, and those with no nationality were included with those who did not state their nationality. 26 Of these 138,136, 104,016 – 75% - were Church of Ireland. 27 Whereas in the published Census Religion volume ‘Protestants’ are included - for unexplained reasons - in ‘Church of Ireland including Protestant’, here they are recorded separately and included with ‘Other Stated Religions’. The author is grateful to the CSO for providing some additional data on ‘Protestants’ for 2002 and 2006. 28 There were 800 females for every 1,000 males among those tourists and visitors who responded ‘none’ (675 for residents), and 886 females for every 1,000 males who made no statement (781 for residents). 29 ‘% born’ refers to the percentage of those who were resident in the Republic and who were born outside the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom. 30 Of the responses listed in Table 4, Baptist and Jewish have been separately identified in each census since 186130. National totals (only) have been published for Lutherans and Quakers since the Second World War: there were 401 Lutherans in 1961 and 830 in 1981, 727 Quakers in 1961 and 642 in 1981, 481 Baptists in 1961 and 924 in 1981, and 3,255 Jews in 1961 and 2,127 in 1981. It is possible that the term ‘Protestant’ was still being used even in 1991 by some people – perhaps in some rural areas – who might more recently have described themselves as ‘Church of Ireland’; in 2002 and 2006 rather less than 10% of those who used this term were born in the Republic. 31 Regional Authority Areas as defined under the Local Government Act, 1991, Regional Authorities Establishment Order, 1993. Dublin: Dublin City, Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown, Fingal, South Dublin; MidEast: Kildare, Meath, Wicklow. 32 Data for ‘Protestant’ for individual regions has not been made available for 2002 when the State total was 3,104. 33 Those ten states which joined the European Union in 2004: Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. 34 Taken from Table A7 in Non-Irish Nationals living in Ireland [data for the British (UK) not included]. Nationalities Roman Catholic Total 35 nine Polish Lithuanian Nigerian Latvian 110,808 % of total 3 Chinese German Filipino French 4,777 American (USA) 7,716 57,715 20,297 3,995 544 3,029 8,057 4,678 170,049 4 63,276 24,629 16,300 13,319 12,475 11,167 10,289 9,548 9,046 Boxes were provided for each of: Roman Catholic, Presbyterian Church in Ireland, Church of Ireland and Methodist Church in Ireland. The ‘Other’ box carried with it a rubric ‘please write in’. 36 Standard Table S308, Religion by Sex 37 There are no groups with between 305 and 542 adherents. 38 Calculated by taking 1991 and 2001 data together: Females/Males. 39 This author has merged the following: Elim includes Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle and Metropolitan Church; ‘Protestant’ includes ‘Protestant (Mixed)’; Reformed Presbyterian includes Reformed; Non-Subscribing Presbyterian includes Unitarian; Evangelical includes Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches; ‘Non Denominational’ in 2001, ‘Undenominational’ or ‘Unsectarian’ in 1991; Christian Fellowship Church includes Christian Fellowship and Fellowship Church; Church of God includes Churches of God; Orthodox includes Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox.