the transatlantic nanny: - Center for Peripheral Studies

The Transatlantic Nanny:

Notes for a Comparative Semiotic of the Family in English-Speaking Societies

Lee Drummond, Center for Peripheral Studies

Prefatory Note: A Little Whiff of Carrion

Could it be that wisdom appears on earth as a raven, inspired by a little whiff of carrion?

—Friedrich Nietzsche,

Twilight of the Idols

The following essay is a somewhat edited and revised version of one published in a special issue of the American Ethnologist in 1978. The issue addressed the topic of American kinship, and specifically in the context of David Schneider’s pathbreaking work on that subject. While I have great admiration for Schneider’s work, the circumstances of the publication of the AE issue troubled me. In retrospect I see that my uneasiness was triggered by a nascent concern for the legitimacy, really, the intellectual honesty of the discipline of cultural anthropology as a whole. I believe it was on the occasion of the issue’s publication that I caught that first whiff of carrion of which Nietzsche speaks; I caught it and, just possibly, at that point began to grow a bit wiser. Let me explain.

My essay examines kinship categories in several English-speaking societies, and in the process attempts to make some fundamental points about the culture of kinship and about internal variation within a cultural system. Those ideas have been developed further in American Dreamtime and “Culture, Mind, and Physical Reality:

An Anthropological Essay.” While I think the essay makes some valid arguments, it is, at bottom, a semiotic juggling act – a waltz of the categories. Of the several papers presented at the symposium which gave rise to the AE issue, I found one in particular a dazzling, profound piece of work. Its author was Ted, or Theodore, Kennedy (the

Afro-American anthropologist, not the late senator), and it dealt with the culture of kinship in Afro-American families.

Kennedy’s piece was a radical analysis, a genuine bit of heresy uttered in the sanctorum of Cultural Anthropology, where a formal celebration of Schneider’s work was underway. As Geertz (I believe it was Geertz) said of Malinowski’s diary when it was published, Malinowski committed an unpardonable sin: he spoke the truth in a

public place. In the modern classic, The Right Stuff , Tom Wolfe describes a favorite theme among his test-pilot subjects: Chuck Yeager and his cohorts were fond of talking about “breaking the envelope” when they tested experimental airplanes. Mach

1, Mach 2, Mach 3, as each envelope approached there was a natural resistance and fear that it was unbreakable, that a “demon lived out there at Mach 1,” etc, which would spell disaster for the hapless pilot who challenged it. At that symposium on

American kinship, Ted Kennedy pierced that envelope. And, indeed, it appeared that there was a demon out there to thwart him.

The context needs to be understood. Schneider’s work on the culture of kinship was indeed revolutionary, but like all revolutions it retained considerable baggage from the Old Order. That baggage was tagged with a familiar label, one that persists to this day: whatever kinship was or, more importantly, was not (actual genealogical ties),

Schneider claimed it was characterized by “diffuse, enduring solidarity.” Despite great diversity in kin terms and behaviors, kinspeople were said to subscribe to a generalized, warm-and-fuzzy feeling toward one another which they did not manifest toward outsiders. It is important to know that Schneider’s idea was firmly rooted in the theoretical framework of Talcott Parsons, at whose renowned Department of Social

Relations at Harvard Schneider was a graduate student. Steeped in Weber and Kant from his studies in Germany, Parsons crafted an entire social theory around a

Gemeinschaft / Gesellschaft – like set of “pattern variables,” which were in turn later codified into his famous two-ply paradigms of AGIL boxes. Schneider’s “diffuse, enduring solidarity” fitted snugly into the best-known pattern variable, ascription vs. performance. All social action, Parsons claimed, could be parsed into behaviors in which individuals relate to one another either on the basis of some assumed, intrinsic, shared commonality (ascription) or of an assumed distance and difference

(performance). Kin ties are ascriptive: regardless of your behavior, you remain a member of your family. Blood is thicker than water. In the wider world of work, school, and society in general, however, people evaluate you on the basis of your performance: you are what you do.

The symposium and subsequent publication celebrated variations on the theme of kinship as diffuse, enduring solidarity. That was the mostly unquestioned background of the individual papers. Except for Ted Kennedy’s. On the basis of his fieldwork in a rural Afro-American community and of his personal experience as an

Afro-American, Kennedy presented a paper entitled “You Gotta Deal With It” in which he proposed that the dominant force in the black family is performance, not ascription. Historically and through the present day, life for most American blacks is a day-to-day struggle, and being perpetually up against it they have little time for individuals – whether “relatives” or not -- who do not contribute to the domestic group.

A birth mothers who is a drunk, addict, or just hopelessly downtrodden and who leaves

2

her child with her own mother or another female relative, a biological father who abandons mother and child or merely drifts in and out of their lives ceases to be a member of the family. Someone who, for whatever reason and with whatever genealogical connection (if any), is prepared to shoulder the burden of caring for an infant or child, who appears to give a damn, becomes the principal kinsperson.

“Kinship” is all about performance, not ascription. Sitting on the panel in that crowded conference room as Kennedy delivered his paper, I could feel the air being sucked out of the room. He had just punched a large, ragged hole in the “diffuse, enduring solidarity” envelope and the gas bag that is cultural anthropology was collapsing around us.

But not to worry. When it came time to edit and review symposium papers for publication in that august journal, American Ethnologist , (whose myriad readers number in the hundreds) Kennedy’s piece did not make the cut. I really don’t know what happened, what discussions took place between the convenor of the symposium and the AE editor, and, of course, what the all-important anonymous peer reviewers had to say. I’m confident, though, that the ludicrous process of peer review returned a negative verdict; Kennedy’s paper was the very opposite of the safe, pedantic, unimaginative stuff that chokes anthropology journals. I doubt many anthropology reviewers have read that literary critical essay by Coleridge in which, responding to peer-reviewer types of his day, he declares “there are still fountains in this world.” An irony here is that other reviewers, in the wider world of book publishing, took a different view: two years after the AE issue appeared (and instantly disappeared into the dusty oblivion of library shelves), Oxford University Press published an excellent, very well- received work, You Gotta Deal With It: Black Family Relations in a

Southern Community by one Theodore Kennedy.

If this little episode, a trivial matter when you think about it, gave off that whiff of carrion I describe, what was behind it, where was the actual carrion, the rotting corpse that gave off its stench? Not to mince words, I would suggest that rotting corpse was the entire edifice of American social research which took shape immediately after World War II. I believe future intellectual historians will look with amazement and horror at the formation at Harvard in 1946 of the Department of Social

Relations and its official platform, if you will, as embodied in the major work of its first chairman, Talcott Parsons: The Social System , published in 1951. In that work

Parsons launched the scheme of pattern variables to describe all social action, and embedded them in a systems-theory framework mostly derived from Norbert Wiener and his concept of homeostasis. Society, the social system, possessed a well-defined set of sub-systems which interacted to produce homeostasis or stability. The structure functioned to maintain itself as a well-integrated, stable whole. This doctrine of

“structural functionalism” as it came to be called spread from the temple of Harvard

3

University to nascent sociology and anthropology departments across the United

States; it became the gospel for indoctrinating future generations of social researchers.

The horror, the sheer intellectual outrage and travesty of all this, is that Parsons and his eminent cohorts (including an elder statesman of anthropology, Clyde

Kluckhohn) advanced their theory at a time when the smoke had hardly lifted from the great killing fields of World War II and when the stacks of rotting corpses still gave off a stench that should have been discernible even on the Harvard campus. Some seventy million people were killed in that war, and surely at least an equal number left maimed or with permanently blighted lives; how could any rational person advance the grotesque idea that human society possessed an inherent rationality, coherence, systematicness ? In the shock and shambles of the immediate post-war years it was incumbent on social thinkers to produce accounts of how social processes could lead. over the course of a few years, to cataclysm and horror. Even if they lacked a sense of smell, Parsons et al should have had the rudimentary vision to see that human society is inherently unstable, conflict-ridden, forever teetering on the edge of chaos. Things just don’t make sense; events can’t be slotted into neat analytical categories. Humanity is the very opposite of system theory’s favorite metaphor, the thermostat, which operates on the principle of change things a little bit this way, then change them back the other way, and keep going so that you maintain, yes, homeostasis . A far more accurate metaphor for the nature and fate of humanity, as I have suggested elsewhere, is a runaway train: it’s barreling down the tracks, completely out of control, and God knows what it’s going to hit. But instead of anything like this, the entire academic establishment labored mightily, and at the highest levels, and came up with the totemic

AGIL four-square box to describe all social action. It bore a suspicious resemblance to a university campus quadrangle.

4

The Transatlantic Nanny:

Notes for a Comparative Semiotic of the Family in English-Speaking Societies

Lee Drummond, Center for Peripheral Studies

The essay suggests that systems-building efforts in kinship studies have glossed over significant cultural variability in the institution of mother. A cultural analysis of family structure in Victorian England and English-speaking countries of the

Western Hemisphere focuses on the career of a prominent mother surrogate, the nanny. The diversity of fates experienced by nanny after her transatlantic voyage appears to support the view that the institution of mother is an eminently semiotic phenomenon, enmeshed in a system of meanings that comprises not only the family but also ethnic systems of the Americas.

Because domestic arrangements can be an analytic category which may not correspond to anything as it is defined as a cultural category in a particular culture, the relationship between a woman and the child she bears may be an analytic category which we erect for various reasons, but it may or it may not correspond to any particular cultural category in a particular culture (Schneider 1972:45).

... We take names always as namings, as living behaviors in an evolving world of men and things (Dewey and Bentley 1949:156).

In the divisive history of kinship studies, there appears to have been a surprising unanimity among prominent systems builders on at least one point: the institution of mother is not a critical variable for a general theory of kinship.

Murdock's efforts to demonstrate the universality of the nuclear family (1949:1-22) effectively precluded a consideration of cross-cultural variation in the social role, not to say the concept, of mother and thereby reduced the mother-child relationship to a cipher. In general, ethological arguments also tend to follow this line, emphasizing the biocultural determinancy of the mother-child bond and hence its constant effect on the development of family structure (Weatherford 1975:308-309).

In the other camp, Lévi-Strauss evidently regards the mother's place in a kinship

5

system as a residue of nature and therefore excludes her (except in her role as wife) from his "atom of kinship" (1963:42-46).

This essay suggests that the activities of theory proving and model building have glossed over or simply disregarded significant cultural variat ion in the institution of mother. Mother is neither, in essence, an ethological law that enables us to understand something about human families by watching baboons (or, it now seems necessary to add, insects) nor a genealogical constant that figures automatically in componential analyses of more distant kinship ties. Instead, it is much nearer the truth to see her as what Schneider (1972:37-40) calls a "cultural unit," an element of shared understanding that organizes, but is conceptually distinct from, behavior.

Consequently, this essay is an inquiry into patterns of meaning rather than patterns of social relations.

I will first summarize the argument I will attempt to demonstrate. The starting point is Schneider's (1972:32-37) assault on the concept of kinship advanced by

Morgan and adopted by numerous others, according to which "kinship" is about actual, natural, biological "blood" ties as these are codified in genealogies. Of the many relationships identified in a genealogy by specific kinship terms, Morgan and others would no doubt agree that the most "natural" of these, the one most expressive of a universal biological fact is what we, in English-speaking countries, call

"mother." Fathers, brothers and sisters, aunts and uncles, and so on may be subject to some degree of cultural delineation in the form of notions of conception, siblingship, adoption, and descent, but, for Morgan and followers, the mother is always a particular woman whose relationship to ego is established by the unassailable fact of having given him birth. If, in societies with classificatory terminologies, other women, say, mother's sisters, are also called "mother" by ego, it is understood that the meaning of the term, and the behavior associated with it, refers to that unique woman who is the genetrix and whose relationship with ego provides a model for his relationships with mother's sisters. Similarly, and closer to home, an adopted mother, even if distinguished by the term "step-mother," is thought of and acted toward on the basis of what is known and expected of "real" mothers. Schneider's brilliant critique of the genealogical model here faces what is perhaps its strongest counter argument:

Mother is found in every kinship system and, however culturally based other kin statuses may be, she at least represents an exact correspondence of nature and culture, the inner sanctum of kinship as biology.

I shall argue that Schneider's critique can be sustained and that, far from being

"the most natural thing in the world," motherhood is in fact one of the most unnatural. For one thing, a cultural analysis of Mother can neatly invert the ethological argument: rather than going on about the universal, biocultural innateness of something called a "mother-child bond," the process of conceiving, bearing, and rearing a child

6

should rather be viewed as a dilemma that strikes at the core of human understanding and evokes a heightened, not a diminished, cultural interpretation. The birth of a child is a dramatic intrusion by a non-cultural being into the heart of the domestic sphere.

A woman, in nurturing and protecting that being, establishes a perilous conjunction of opposites: a fully human adult becomes intimate with a nonhuman, even antihuman form.

1

My point, which cannot be developed further here, is that the process of investing a foetus with a human identity is cultural — it gives meaning to the world — and so, correlatively, is the process of identifying a woman as mother.

In making this logical point, I want to propose rather more than an increased appreciation of the role cultural factors play in defining the status Mother.

My argument does not represent the cultural system as an organizing matrix for human biological plasticity - the bender of the twig — but rather as constituting the possibilities of human experience. That experience, I want to claim, must be formulated in terms of cultural categories to occur at all; in happening it is already part of a semiotic system. What is at issue here, then, is not the cross-cultural diversity

(fascinating as that is) in the way that women perform their role as Mother: here she is warm, nurturant, supportive; there she is cool, withholding, critical. The issue is the nature, or meaning, of the cultural unit "mother.” And the meaning of a cultural unit, as Schneider so forcefully argues, is not to be found by directly observing behavior

(how women perform their social roles as Mother), but by identifying other cultural units in the system and establishing the relationship of the first unit to them.

Proceeding in this way, one does not understand culture by asking 'how do mothers act in such-and-such situations?" but by asking, "what is a mother that should make her actions subject to particular interpretations in given situations?"

At this point in my argument, a critic could still object that it is all very well to emphasize the cultural implications of kinship over the biological facts of reproduction, but that motherhood is not a particularly apt subject for such treatment.

Since a majority of people everywhere are reared by their genetrix during their early years, these behaviors are what people think of when they talk about mothers and mothering. According to this point of view culture would simply duplicate biology, and my remarks about the semiotics of the family would mean no more than that people, as culture-bearing animals, invest meaning in biological motherhood. Barnes

(1973) provides an example of this tendency to view motherhood as culturally impoverished in relation to other kinship statuses. Such criticism, however, completely misses the point about the difference between the cultural unit “mother,” and the "real" mother of the genealogists. The point is to ask the question "what is a mother in culture X?" in such a way that one receives an empirical account of how that concept links up with other, associated concepts to form a coherent picture of an intimate, domestic world.

7

We are, at last, to the heart of the argument. Equating genetrix with the cultural unit “mother” is an error, not just because it fails to give the proper perspective, but because the assumption that one, unique woman must be Mother is not always supportable and, in fact, is demonstrably false in some cases. Furthermore, in the cases I examine here, not only is more than one woman involved in establishing the meaning of the cultural unit “mother,” but these women represent fundamentally different social categories. In discussing the ethologicai argument, I noted that a woman and her new-born infant belong to different orders of being. If we can construe anything of the infant's phenomenology, it would seem to be its perception of mother as other — in realizing that it is interacting at all, the infant acquires the distinction between itself and some Other who is also a volitional being. In claiming that women other than the biological mother contribute substantively to the notion of

Mother, and that different social categories are involved, it follows that the infant or child begins to perceive the Other as Mother — the social world paradoxically acquires discreteness for it in the very process of assimilating the behaviors of diverse women to the concept of “mother.” This last point leads to some intriguing implications of Schneider's idea (1969:116-125) that the symbol system of kinship is bound up with the symbol system of nationality or, as I will call it here, ethnicity.

In what follows I shall try to breathe some life into the argument outlined above by considering the nature of “mother” as a cultural unit in several historical and contemporary English-speaking societies: England, Jamaica, Guyana, and the United

States.

2

While I apologize for the brevity of the individual case studies, I recommend the cultural analysis of kinship in English-speaking societies as a promising comparative approach. These societies possess a common language, which includes a common set of kinship terms, and are all historically related to a single society,

England. If it is possible to identify cultural changes in the kinship systems of these societies — that is, changes in the cultural units of kinship and not just social role performance — then we will be closer to understanding processual operations in culture as a whole. Also, as Schneider has noted, the task of cultural analysis in kinship studies is so complex that one is practically confined to one's own culture and language.

The immediate inspiration for this comparative study of cultural units is

Boon's intriguing comment (1974:137-139) on Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy's book The

Rise and Fall of the British Nanny, or as published under its (revealing) U.S. copyright title The Unnatural History of the Nanny (1973). The nanny, as an institutionalized mother surrogate responsible for rearing several generations of middle- and upper-class Englishmen, is certainly an apt subject to introduce into this discussion of cultural versus "real" mothers. Boon suggests that the nanny represents

8

a further theoretical erosion of the concept of a universal, bioculturally-based family unit. If Goodenough (1970), Gough (1959), Smith (1956), and others have revoked the father's guaranteed membership in the nuclear family, reducing that construct to some variant of a woman(en)-child unit, then Boon would deny even the mother's inalienable right to belong. With Gathorne-Hardy, he notes that a complex, classstructured society like nineteenth-century England can allow some of its women to acquire full-time mother surrogates. The "nanny-reduced mother," Boon suggests, is perhaps an early methodical step in a process of generalized "cultural reduction" of the mother's diffuse role, a process now most evident in the industrialized nations of Western Europe and North America.

3

Boon's recommendation that we examine "nanny centric" premises in anthropological discussions of the family rests on the curious fact that theories of kinship, and anthropology as a whole, have been greatly influenced by nannied children who went on to become anthropologists. For the present, however, I must leave it to others to ponder whether the “universal” nuclear family has been championed by those who mourned its absence in their own lives. My interest in the nanny/mother cultural complex centers on the fact that the heyday of the nanny, besides coinciding with the birth of anthropology, was also a period of intensive colonial activity on the part of Englishmen around the world. And the colonists brought with them to their new homes in the New World a set of cultural categories of kinspeople, among them being the nanny. Asking how nanny fared after her transatlantic voyage is thus an excellent way of beginning to explore the general question of cultural units associated with mother in the English-speaking world.

I must first examine the background of mother surrogation in England.

Gathorne-Hardy's book is a fascinating account, not just of nannies but of English child-rearing practices since medieval times. It is written with a sense of outrage, for

Gathorne-Hardy believes in mothers; that is, he believes that the woman who has a baby should also nurse it, tend it, and when it is older, be its friend and guide. His outrage is directed at the whole centuries-old tradition of wet nursing, fosterage, and the apprenticing of children that preceded nanny's reign in the Victorian nursery, all of which he sees as contributory strands to "the English ability to allow others to look after their young" (Gathorne-Hardy 1973:36). Long before nanny appeared on the scene, then, the cultural unit “mother” in the English kinship system operated in the field of other, well-established units like “nurse” and “foster mother.” Granted the history of mother surrogation in England, I find it puzzling that Gathorne-Hardy should ignore his own evidence and regard nanny as exceptional. "The unnatural history of the nanny" is anything but that: nanny is perfectly "natural" in the sense that she represents a consistent transformation in the system of cultural units related to the unit “mother”. That transformation may be represented thusly:

9

[MOTHER (genetrix + wet nurse) ————→ MOTHER (genetrix + nanny)]

If we see nanny as but one transformational element in a mother-surrogation system, then Boon's reference to her as an instance of "cultural reduction" may be interpreted to mean "cultural elaboration" or even "cultural amplification." The experientially and conceptually indistinct genetrix is given both a social identity and a cultural meaning in her association with a nanny. The mother who employed a wet nurse through her child's second year and then gave him out as apprentice three or four years later is no more or less surrogated than the Victorian mother who nursed her child and then entrusted him body and soul to a nanny. Both cases exemplify what we really must confront in a cultural analysis of English/American kinship, that is, the generally ignored "English ability to allow others to look after their young" to which Gathorne-Hardy has alerted us. Where nurse and nanny are present, the cultural unit “mother” operates in a field of other, conjoined cultural units that together provide the notion of motherhood with its distinctive meaning. These interrelated cultural units thus constitute a semiotic system, and transformations within that system define the types and boundaries of Mother in the English-speaking world.

4

I now come to a crucial part of the argument. With Boon and Gathorne-

Hardy, I have claimed that the cultural unit “mother” was not a monistic, univocal concept for middle-and upper-class Victorian Englishmen. The unit incorporated different women. But we should consider how very different they were, for the institution of nanny was possible only because English society was highly differentiated by class. Two implications follow from this. First, nanny and genetrix derived their cultural meanings from their close conjunction, but part of those meanings, built into them, is that they represented fundamentally different orders of society or social categories: the nanny is not of the same class as genetrix.

This is a concrete example of the point I made earlier about the Other as Mother: the nannied child cannot assimilate, assign meaning to, the cultural unit “mother” without taking into account both the person and the cultural unit “nanny.” But in conjoining them he cannot fail to see that nanny and genetrix possess exclusive statuses.

Hence, in coming to understand what is closest to him he also comes to understand categories of inherent, "natural" social distance, or, again, ethnicity. He acquires a consciousness of kind. I suggest that this dialectical process is at the root of the relationship between kinship and nationality or "moral community" that Schneider has discussed.

5

The second implication is that nanny and genetrix and, before them, wet nurse

10

and genetrix were conjoined statuses that did not have a common meaning at all levels of English society. Women of all classes had babies, but not every woman had a nanny or wet nurse. The social classes of nineteenth-century England constituted an asymmetric exchange system: they were divided into nanny-givers and nanny-takers.

Bearing and rearing children posed very different problems for the two groups. For the nanny-takers, the "real" biological mother claimed her child and gave it over to nanny to rear (in Schneider's terms, mother was a "blood" relative because she combined the order of nature and the order of law). But what of women from nanny-giving classes? Many of them were truly "culture-reduced" mothers in that their children were the offspring of impermanent unions (the order of nature) and, because the women held residential servant jobs in households of nanny-takers, their children were entrusted to the care of others (mother's female relatives) or given up as foundlings. The child characters of Dickens’ novels are the other face of the society whose nannies and nurseries are described in Gathorne-Hardy's book.

This historical situation, however imperfectly I render it, is really the social - structural manifestation of the Other-as-Mother dialectic. If nanny-givers and nanny- takers had, as a rule, extremely diverse experiences of motherhood and entirely different mother surrogates (nanny on one hand, grandmother or foster mother on the other), then what are we to say about the nature of the cultural unit “mother”? Is

Mother a single, dominant symbol that, despite normative variation in the society, is nevertheless a constant in the cultural order? I suggest that she is not, that, in historical

England, the otherness of mother and social-structural differences in mothering combined to produce quite different cultural complexes of ideas surrounding the cultural unit “mother”: the vague notion of "real" mother was assimilated, at various times and among various classes, to the cultural categories “wet nurse,” “nanny,”

“grandmother”, “foster mother,” and so on. These assimilations produced integral constructs of Mother that are semiotically related, but by no means identical: they are variations, or transformations, of a theme. An alternative to thinking of a cultural unit as a univocal or invariant property of a conceptual system has been provided by, among others, Derek Bickerton (1975). His analysis of Guyanese Creole speech posits the existence of a continuum that is absolutely indispensable to understanding grammatical variation in Creole. To put it very briefly, Bickerton asserts that Creole contains not one grammar, as Chomskyian linguists would claim, but several, that are interrelated for the individual speaker and at the formal level by transformational rules. I suggest that Bickerton's idea of a grammatical continuum be adapted to form a conception of a cultural continuum of kinship categories embracing contradictory, but semiotically related, units of Mother.

I believe that viewing the English/American kinship system, at least as far as

Mother is concerned, as a cultural continuum makes the task of following the

11

transatlantic nanny on her several voyages a good deal easier and more meaningful. For one thing, we embark knowing that the diffusionist model is already in shambles: it is hopeless to attempt to chart the twists and turns of a single set of univocal cultural units of English kinship, because the parent system is itself sharply polarized. Since there is no set of cultural units with invariant meanings, we must seek to determine which meanings figure in particular colonial cultures of the New World and, most of all, how those meanings are arranged into a semiotic system that, neither duplicating nor abandoning the parent system, transforms it.

In the Caribbean, English kinship categories were assimilated by a plantation society based on the cultural division white master / black slave rather than the

Victorian division upper class master / lower class servant. The contradictory elements of the nanny/mother complex were thus accentuated by the imposition of an ethnic category system that denied humanity to persons — black nurses — who performed the intimate duties of mother for white children. The Other as Mother took on alarming proportions for perceptive white bigots, as this passage from

Edward Long's eighteenth-century history of Jamaica makes clear.

White women take on the habits of slaves and disdain to suckle their own . . . offspring! They give them up to a Negroe or Mulatto wet nurse, without reflecting that her blood may be corrupted, or considering the influence which the milk may have with respect to the disposition, as well as health, of their little ones (Long 1774:276).

To protect their children from degradation by Creole customs and language (as well as milk), Long notes (1774:278) that some planters imported English governesses.

Here we see Nanny making her transatlantic voyage as a kind of cultural shock trooper whose mission was to eradicate the deleterious effects on her charges of their former black nurses and their own creolized mothers. The cultural unit “mother,” in late eighteenth- century Jamaican planter society is therefore intelligible only when considered in conjunction with the cultural units “black nurse” and “nanny”

(governess). The transformational expression for this twist in the English system of kinship categories may be written as follows:

Upper-class England —————→ Eighteenth-century Jamaican planter society

[MOTHER (genetrix + nanny) MOTHER (genetrix + black nurse + nanny)]

Nothing is postulated here about the historical relationship of these expressions; they are connected by virtue of their meaning.

The internal semiotic structure of the Jamaican cultural unit “mother” is at least as polarized as that of Victorian England. Black slave women as well as their

12

white mistresses bore children, only the former did not share their identity as mother with imported governesses. The literature on black families in the Caribbean amply demonstrates the distinctive matrifocal family structure which evolved under conditions of slavery and the plantation economy (Smith 1956; Clark 1957). In the matrifocal family, the black woman had no paid mother surrogate, nor often a husband, to assist her in caring for her children.

A critic might surely pounce on this mention of the matrifocal family and claim that here, at least, the genetrix is also the social mother, that mother surrogates are absent, and that the cultural unit “mother” is therefore synonomous with the biological facts and social roles of the genetrix-child relationship. Such criticism, however, assumes what it would demonstrate: that Mother is a known entity. Were this the case, the matrifocal family would be perfectly explicable in terms of the universal fact of motherhood. I suggest that the contrary is nearer the truth. It is precisely in the matrifocal family, or, specifically, some Guyanese variants of it, that the conceptual distance between the genetrix and the cultural mother is most pronounced. So pronounced, in fact, that the (or a) Guyanese system of kinship categories commits the genealogical heresy of using the kinship term "mother" to apply to a woman who is not the "real" biological mother at all.

In the Guyanese Creole system "mother" or "mommy" is the maternal grandmother, who is the usual head of the matrifocal household. What, then, does a child call its "own" mother (to frame the question in geneaological terms)? It calls her "auntie," usually followed by her first name – “Auntie Mary," for example.

This rearrangement of English kinship terminology is perfectly consistent with the facts of matrifocal family life as Smith (1956) and others have described them. A young woman has her first child while still living with her parents and under their guidance. Her male partner, even if a regular visitor, is generally not in a position to support a family. The woman's child is thus incorporated into her mother's household, where the child's grandmother stands in the directive position that we gloss with the cultural unit “mother.” The young woman's sisters, if present in the household or its immediate neighborhood, are also called "auntie;" hence first names are used to specify the individual. I have observed exactly this situation and usage pattern in Guyanese rural households on an almost daily basis over a period of two years.

Furthermore, the transformations in the Guyanese system extend further than the cultural unit “mother”: grandfather may become father. What happens to father? He is called “brother,” or, really, big brother. In his fascinating autobiography Son of Guyana, Arnold Apple (1973) describes his childhood in the

Guyanese countryside and slums of Georgetown. Referring to his relations with his birth mother and itinerant father, he says,

13

My mother, brothers, and sister would make it clear to me, "Buddy is not here now." Buddy was our Dad, but as all of his brothers and cousins called him Buddy, all of his children called him the same.

The same thing goes for my mother, we never called her "Mummy," we called her Auntie Gladys; this was because Aunt Leah [Gladys’s sister] had five children, and we all grew up together, and they called our mother Aunt Gladys, and we called their mother Aunt

Leah. So like that, the constant ringing of "Aunt" in our ears caused us to call our mother "Aunt" instead of mother. Had it been the other way around, we would be calling our Aunt mother, too

(Apple 1973:8).

The Guyanese case contrasts sharply with the mother/nanny complex of

Victorian England, in which an outsider is insinuated into the domestic group. In the Guyanese system the social status of the genetrix is appropriated from within the domestic group, so that that a woman and her female relatives represent an overemphasis on mothering through blood ties:

[MOTHER = (genetrix + mother's sister / "auntie" + grandmother / "mommy")]

If a woman's female relatives, because of their social and conceptual closeness, become identified with her in the cultural unit “mother,” what becomes of our transatlantic nanny in the Guyanese matrifocal system? Apple dedicates his book to "Nana and Aunt Gladys," the latter being his genetrix. Nana, the “adopted mother” of his wife, was a “fussy lovable woman about sixty-five years old” (Apple

1973:83), to whom Apple was shown as soon as he began courting her. Nana was, it appears, related in some way to his wife and became an "adopted mother" to her because she lived in town, was fond of her, and could look after the girl when she left her country home. If the term "nana" is in fact derived from British English

"nanny," it is intriguing that it should be found, not at the highest, but at the lowest levels of social stratification in the Guyanese Creole system. "Nana," both in

Guyana and Jamaica (see DeCamp 1971:355-356) is regarded as indicative of the

"broken language" or "deep Creole" speech of uneducated peasants. In the absence of conflicting historical documentation, it is tempting to speculate that the process of diffusion of the cultural unit and the social status “nanny” has not been from the top down, with upper- and middle-class Creoles gradually acquiring minor versions of the British nanny for their own children. Instead, and through whatever historical circumstances, nanny's transatlantic voyage has taken her, in

14

Guyanese Creole culture, straight to the lower echelons of society. To have a

"nana" is lower class.

I believe that the reason for Nanny's demotion must be sought in the application of the English cultural continuum of kinship to West Indian plantation society. The institution of Nanny was possible only in a class-stratified society, which was based in part on a sharp contrast between the systematic underemphasis on mothering through blood ties among the upper class and a corresponding overemphasis among the lower class. The colonial venture did not, therefore, involve the imposition of a single cultural model on culturally dispossessed slaves, as much literature on colonialism implicitly assumes, but of a dialectically organized cultural continuum that, at its extremities, contained mutually contradictory elements (just as the Guyanese speech continuum analyzed by Bickerton contains conflicting grammars at its extremities). In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, white Europeans with undistinguished pedigrees were employed in various positions on the sugar plantations of the West

Indies (Brathwaite 1971:142-144), where they interacted with slaves on a daily, intimate basis. In that setting those lower-class Europeans could surely have insinuated their understanding of English kinship categories into the developing

Creole culture.

In the transformational system of English kinship, underemphasis of mothering through blood ties in Victorian England created a pseudo kinswoman,

Nanny. In sharp contrast, the overemphasis of blood ties characteristic of maternal relations in the slave societies of the Caribbean has resulted in a skewing of the customary genealogical-cultural associations. Specifically, the following set of transformations appears to operate in the Guyanese cultural continuum of kinship described by Apple: genealogical mother ————→ “auntie” genealogical grandmother ————→ “mommy” genealogical senior kinswoman (aunt?) ————→ “nana”

The English cultural continuum of kinship is stretched further in the

Guyanese case than in that of Victorian England, where divisions of class are less radical than divisions of race. In the parent English continuum Nanny can be a blood relative, for the grandmother as nanny is an institution: grandmothers have commonly been called "nanny" for the past two centuries in Wales and the North and Midlands of England (Gathorne-Hardy 1973:68). Here again we are probably looking at the two polarities of Victorian society: for some children Nanny was an unrelated outsider, while for others she was their (usually maternal) grandmother.

15

In the Guyanese system, however, that genealogical position became culturally encoded as "mommy." The problem, if it can be called that, was then to retain

Nanny as a blood relative (in accordance with lower-class Victorian English usage) and find a genealogical slot for her — hence Apple's "nana." A kinswoman participating in the maternal complex ("adopting" Apple's wife) who is neither the genealogical mother nor grandmother (neither "auntie" nor "mommy") must be fitted into the cultural system of kinship somewhere. Invoking the transatlantic nanny as a solution provides both an identity for the significant kinswoman and a certain continuity between kinship systems.

Nanny as blood relative figures in an internal transformation of the Guyanese system, this time involving East Indians of the Essequibo Coast whose family ties have a strong patrilateral bias in comparison with black Creoles. Nanny and, indeed, the whole complex of ideas of maternal nurturance and protection, appear to be skewed toward all of mother's relatives: mother's mother is called nani ; mother's father is nana ; , mother's brother is mamu ; mother's brother's wife is mami .

The meaning of the cultural unit, “nanny,” in the East Indian Creole variant of the Guyanese cultural continuum of kinship is close to that in the lower-class Victorian English variant. In both cases she is an older kinsperson and, ideally, more a nurturant and protective figure than an authoritarian one (since she is not a patrikin). And in both cases, she is an actual, geneaological grandmother. These various usages of maternal terms are discrepancies only if one insists on identifying particular kinship or pseudo-kinship categories with particular genealogical (or non-genealogical) positions. The meaning of kinship categories can only be determined by the uses to which they are put in the language, and if it is correct to postulate the existence of a cultural continuum of kinship, then we may expect those usages to be openly contradictory at times.

6

The theme of grandmother as Nanny also appears in a third English-speaking society of the Americas, the United States. Schneider's original inquiry into the nature of American kinship as a cultural system (1968) has prepared the way for a systematic examination of diversity within that system. The fascinating project of fitting

Anglo-American, Afro-American, Native American, Mexican-American, and numerous other complex ethnic kinship systems into a comprehensive semiotic analysis of the culture of kinship in the United States has only begun. The present investigation of the maternal complex in English-speaking societies indicates that variations on that theme must be regarded as integral parts of a cultural continuum: as with Lévi-Strauss's totemic classes, it is the differences and not the similarities in

American concepts of kinship that make the system hang together. Within the cultural continuum of the United States the cultural unit “mother” embraces much of the diversity I have noted in other English-speaking societies. In addition to being defined in the context of the units “nanny” and “granny,” the maternal complex

16

incorporates, historically and regionally, a third, “mammy.” The black nurse in the

American South serves as a link between North American and Caribbean continuua and, perhaps even more than her Jamaican counterpart discussed above, brings into sharp relief the intimacy of the contradictions generated by the dialectic of kinship, class, and ethnicity. To learn that the woman who suckles and tends you is another, perhaps subhuman, order of being is to know the full meaning of the Mother-as Other.

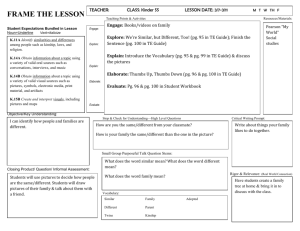

Figure 1 (see below) depicts the semiotic field in which the cultural unit

“mother” has operated in American society. A satisfactory account of those operations would require at least another essay, but it is possible here to sketch in the outlines. Among any particular social group at any given time (and, perhaps, at discrete periods of the family's developmental cycle) the maternal complex is shaped by the relative emphasis placed on mother surrogates. These women are defined according to dominant ideas in American culture: blood (kinship); race (ethnicity); and business (class). The contemporary emphasis on impersonal, quasi-contractual arrangements for mother surrogation in American life (the babysitter, the day care center, Head Start, and so on) appears to make Nanny's twentieth century surrogates the most important polarizing force in the maternal complex. At the same time, Nanny retains her lower-class Victorian identity as blood relative in some sections of

American society.

7

Historically, nanny and granny could both be defined by the idiom of blood, or geneaological kinship. In this they differed fundamentally from the black nurse, or mammy, whose identity depended on the theme of separation rather than incorporation. If mammy's participation in the American cultural continuum of kinship is now only a memory from the past, this does not, unfortunately, mean that the polarization of kinship and ethnicity has diminished in

American life. The powerful and ambivalent emotions stirred by the nonisomorphism of kinship and ethnicity, by the complex rather than univocal nature of the cultural unit “mother,” are expressed in cognitive-affective systems (semiotic dimensions) that I have not attempted to treat here (see American Dreamtime , Chapter

3, “A Theory of Culture as Semiospace”). Nanny/Mammy as Mother was also

Nanny/Mammy as sexual being, to varying degrees and in varying ways, in the cases mentioned above. Expressions of sexuality, from the sublime to the grotesque, can and must be examined as interrelated, meaningful features of an American cultural system of symbols and meanings.

17

In this essay I have tried to demonstrate that a cultural analysis of kinship is essential to a satisfactory understanding of a particular kinship category, Mother, found in English-speaking societies. My argument has sought to reverse the usual tendency in kinship studies to regard the cultural unit of “mother” as biologically and socially constrained by the physical facts of reproduction and nurturance. Instead,

I follow Schneider in viewing the biology of kinship as itself culturally constituted: the “facts of life" are not the laboratory reports of geneticists and molecular biologists, but common understandings of what is involved in being related to someone or being in love with someone. And not only is the cultural unit “mother” not tied to physical necessity: it is not even internally consistent. The ontogenetic process of mother-infant attachment involves the child defining the mother as both the same and different; what is closest becomes a model for what is furthest away

18

(Mother as Other). The historical and social-structural circumstances of the Englishspeaking societies included in this study have produced a second inconsistency, in the form of mother surrogation. This practice brought together within a single maternal complex women of sharply contrasting social backgrounds, whether defined in terms of class or race (Other as Mother). The examples cited indicate that the cultural definition of Mother results from a relative overemphasis or underemphasis on blood ties with women, as these are conceived to center on the genetrix.

The central problem addressed in this essay is cultural variation within a set of kinship categories. I have argued that the cultural unit “mother” is internally contradictory, and it should be emphasized that this means more than simple normative variation in the way particular women in particular societies mother. The several maternal complexes examined here, consisting of alliances of genetrix, nanny, grandmother, nurse, babysitter, and so on exist because the societies in which they operate are highly polarized by race, class, or some combination of the two. It follows that the cultural unit “mother” in English-speaking societies cannot be an monistic concept with a univocal meaning but must be understood, probably along with other kin categories, as part of a system of differences . If a society has nannies and/or black nurses, it must have discrepant conceptualizations of Mother. How is the notion of a cultural unit as a set of dialectically paired opposites to be accommodated within anthropological theories of symbolism and meaning? I have suggested, more by way of analogy than formal argument, that this can be done only by moving from the concept of a semiotic system as the bearer of underlying, constant meanings ("deep structure" and "armature" are terms that come to mind here) to a concept of semiotic system as a continuum that embraces mutually incompatible meanings. Obviously a great deal more attention needs to be given to this problem, and in the present context I have only hazarded the remark that recent studies of Creole language may contain some useful clues. These are attractive if only because they utilize the notion of transformations within a system as the principal analytical device for handling diversity. This essay is an initial effort to study transformational relationships within a class of English kin categories in order to determine something about the culture of kinship in particular societies.

Finally, identifying pronounced cultural variation within a single society's kinship system raises an issue in the anthropology of colonialism. “Plural societies” are supposed to have resulted from the incomplete assimilation of diverse peoples within a single social order. The unstated premise to this familiar argument is that the separate peoples originated in cultures that were integrated, stable wholes. The only problem was in shaping these disparate totalities into a viable postcolonial culture. This argument strikes me as overly simple and misleading, although it has

19

certainly made good ideological currency. Rather than see “pluralism,” conflict, and contradiction as the result of the colonial process, we might more accurately view them as its preconditions. The English colonial enterprise is unintelligible without reference to the class structure of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century

England. The social boundary that separated the nanny from her employer was also present in the colonies of the West Indies. There the upper-class white planter and the lower-class white plantation artisan recreated, and transformed, different Englands in the context of rapidly changing slave societies. The Creole cultures that have resulted from this process are necessarily diverse in their internal organization. To comprehend that diversity requires a fundamental reworking of the received wisdom that cultures — whether primitive, Western, or postcolonial — are wholes.

Notes

1 The mother-infant relationship as described here may be the basis for an ontogenetic argument concerning the self/other opposition. Ainsworth's studies (1974:61-

64) of the child's attachment to its mother — its cathexis of her — reveal striking differences between that process and the phenomenon of "imprinting" that Lorentz has done much to popularize. While a gosling at a definite point in time fixes on an object — whether a mother goose or an ethologist on his hands and knees — the infant goes through distinct phases of differential responsiveness to nurturant adults. The behavior exhibited reveals the complexity involved in selecting responses to mother and others, and makes ethological notions of mother-child "bonding" appear overly simple. Self/other distinctions are thus grounded in some pre-conceptualization process that extends well into the second year of life, when the infant acquires what Piaget (1954) calls an "object permanence" concept of its mother.

2 Discussion of these cases is extremely abbreviated here and does not even touch on the theoretically interesting case of nineteenth -century Belize (Sanford 1974:504-

518), where the Victorian pattern of mother surrogation is completely reversed. Rather than a lower-status woman (nanny) establishing residence in a higher-status household to care for its children, the Belize post-Emancipation practice of "apprenticeship" sent young

Carib boys (around six years of age) from their lower-status maternal homes to live in higher-status Creole homes until they reached adulthood.

3 Practices of mother surrogation in contemporary American society deserve to be considered in terms of how they affect the meaning of the cultural unit “mother.” As a beginning, it would be interesting to know how much of mothers' and children's time is

20

actually consumed by interactions of the nurturance-dependency kind stipulated by

Goodenough (1970:36). Widespread acceptance of contraception and abortion, proliferation of day care centers for working mothers, increased reliance on nursery schools and educational television, and the ethic of sexual egalitarianism applied to child care

(which belatedly returns the banished father to his brood) are nearly as effective as Nanny and her nursery in removing genetrix/mother from the children's experiential world. Perhaps

Nanny has been eclipsed in modern American society by a perfect nanny surrogate, the babysitter, whose function in the household is more nearly fitted to the urban and suburban pace of middle-class families. If the Victorian manor with its retinue of servants was more corporation than household, the middle -class home many of us know is more way station, equipped with individualized living and entertainment centers where adults host adults, children host children, and everyone is perpetually about to be on his way.

4 Speaking of a "semiotic," as opposed to a "structural," system is not just an arbitrary choice of terms. To say that the cultural units of kinship discussed in this paper are semiotically related asserts that those relationships figure in actors' understanding of the world and are not purely analytical creations. I take it that the elements of myth that

Lévi-Strauss works with in Mythologiques are usually abstractions of the latter type, while the concepts of “mother,” “nanny,” “nurse,” “auntie,” and so on and the relationships connecting them are of the former. The question of how symbols mean is central to this distinction, as it is to current theoretical discussion (Schneider 1976:206 -

210; Sperber 1975; Drummond 1977). Studying cultural symbols and studying culture as a system of symbols and meanings are, as Schneider has noted, different pursuits. The concept of meaning that emerges from attempts at the latter must, it seems, incorporate the intentional or motivational component of meaning-something.

5 Surely one of the most important of Schneider's numerous contributions has b een to note that kinship, religion, and "nationality" are related symbolic complexes

(1969:116-125). His recent formulation of the notion of "cultural galaxy" (1976:209 -

211) points up the necessity of this perspective to the study of meaning. At the same time, he has refined the notion of "nationality" to that of "moral community," which seems quite near the concept of "ethnicity" as it is now being discussed. How are kinship and ethnicity related within the cultural galaxy? Two interpretations are possible here: one is to stress the similarities between family and nation ("motherland"), characterizing ethnicity as a kind of super-kinship, a metaphorical extension. Another is to posit a dialectical relationship between the two, as I have tried to do elsewhere (1977), so that kinship and ethnicity are seen as inextricably related but moving in opposite directions. Very roughly, kinship operates on a principle of inclusiveness and provides meaning to a category of persons on the basis of incest avoidance, while ethnicity operates on a principle of exclusiveness and defines a category of persons on the basis of whom it is intolerable to marry.

6 The introduction of East Indian material at this point opens an avenue of investigation that cannot be pursued here: the articulation of indigenous East Indian kinship categories with those of Africa, Europe, and indigenous South America in the context of the multiethnic society of Guyana. Whether or not terminological systems have changed since emigration, I would argue that the patterning of kinship sentiment, family

21

structure and, in short, the culture of kinship among Indo -Guyanese must be understood primarily in terms of the Guyanese continuum.

7 Boon's article to which I referred earlier makes a plea for anth ropologists to examine their own “nanny-centric” backgrounds. In view of this, I would be dealing unfairly with my readers if I did not confess at this point to having had a nanny myself, a maternal grandmother, whom I called "nanny" and nothing else, and with whom I lived, along with my "real" mother (whom, incidentally, I did not then call "mother" or any related term) for the first seven years of my life. I leave it to my readers to identify further ramifications of nanny-centrism in our craft.

References Cited

Ainsworth, Mary 1974 Phases of the Development of Infant-Mother Attachment. In

Culture and Personality . Robert A. LeVine, Ed. Chicago: Aldine, pp. 61-64.

Apple, Arnold 1973 Son of Guyana . London and New York: Oxford University

Press.

Barnes, J.A. 1973 Genetrix: Genitor :: Nature: Culture? In The Character of

Kinship . Jack Goody, Ed. London: Cambridge University Press, pp. 61-73.

Bickerton, Derek 1975 Dynamics of a Creole System . New York and London: Cambridge

University Press.

Boon, James 1974 Anthropology and Nannies. Man 9:137-140.

Brathwaite, Edward 1971 The Development of Creole Society in Jamaica: 1770-

1820 . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Clarke, Edith 1957 My Mother Who Fathered Me . London: Allen and Unwin.

De Camp, David 1971 Toward a Generative Analysis of a Post-Creole Speech

Continuum. In Pidginization and Creolization of Languages . Dell Hymes, Ed.

New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 349-370.

Dewey, John, and Arthur F. Bentley 1949 Knowing and the Known. Boston: Beacon

Press.

Drummond, Lee 1977 Structure and Process in the Interpretation of South American

Myth: The Arawak Dog Spirit People. American Anthropologist.

Gathorne-Hardy, Jonathan 1973 The Unnatural History of the Nanny . New York:

Dial Press (originally published as The Rise and Fall of the British Nanny ).

Goodenough, Ward H. 1970 Description and Comparison in Cultural Anthropology .

Chicago: Aldine.

Gough, Kathleen 1959 The Nayars and the Definition of Marriage. Journal of the

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 89:23-34.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude 1963 Structural Analysis in Linguistics and in Anthropology. In

Structural Anthropology . New York: Basic Books, pp. 31-54.

Long, Edward 1774 The History of Jamaica . Vol. 2. London.

Murdock, George P. 1949 Social Structure . New York: MacMillan.

22

Piaget, Jean 1954 The Construction of Reality in the Child . New York: Basic Books.

Sanford, Margaret 1974

Acculturation.

Revitalization Movements as Indicators of Completed

Comparative Studies in Society and History 16:504-518.

Schneider, David 1968 American Kinship: A Cultural Account . Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

1969 Kinship, Nationality and Religion in American Culture: Toward a

Definition of Kinship. In Forms of Symbolic Action , Proceedings of the 1969

Annual Spring Meeting of the American Ethnological Society, pp. 116-125.

1972 What is Kinship All About? In Kinship Studies in the Morgan

Centennial Year . Priscilla Reining, Ed. Washington, D.C.: The Anthropological

Society of Washington, pp. 32-65.

1976 Notes toward a Theory of Culture. In Meaning in Anthropology . Keith

H. Basso and Henry A. Selby, Eds. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico

Press, pp. 197-220.

Smith, Raymond T. 1956 The Negro Family in British Guiana . London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul.

Sperber, Dan 1975 Rethinking Symbolism . Alice L. Morton, Trans. New York and

London: Cambridge University Press.

Weatherford, J. M. 1975 Anthropology and Nannies. Man 10:308-310.

23