Dimaggio`s thesis plays out in the professional arena of U

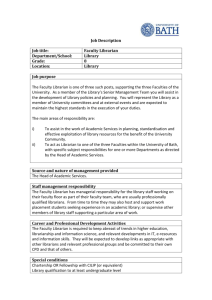

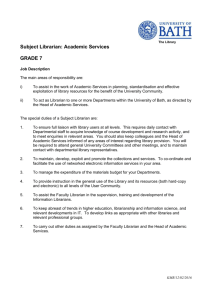

advertisement

The Library as Institution: Understanding Bureaucracy and Organizational Change Janice Cheryl Beaver Information Research Specialist Library of Congress Recent scholarship on libraries has attempted to develop more sophisticated conceptions of how libraries interact with changing forms of technology, media, and culture. To this end, information science has productively engaged social and cultural theories of mediation and language. In this vein, I would like to consider another branch of social theory that I believe can help to elucidate some important issues in librarianship. In particular, I want to consider possible contributions that the “New Institutionalism” can make toward understanding the institutional and bureaucratic nature of libraries themselves, especially in regards to how libraries approach organizational change. In his “Constructing an Organizational Field as a Professional Project: U.S. Art Museums, 1920-1940,” Paul J. Dimaggio describes the tensions within the organizational field of U.S. art museums. He claims that organizational analysis has largely characterized institutional change as “taken-for-granted, nondirected, nonconflictual evolution at the expense of intentional (if boundedly rational), directive, and conflictladen processes that define fields and set them upon trajectories that eventually appear as ‘natural’ developments to participants and observers alike” (DiMaggio, 268). While Dimaggio’s focus is on American art museums, I believe that many of his insights would hold for the ways in which librarianship also considers organizational change. While my juxtaposition of the professional field of librarianship vis-a-vis Dimaggio’s theoretical assertions does not suggest a historical equivalence between the two professional arenas, his essay offers insight into the often unexplored or certainly underexplored dichotomy between those who work in libraries and those writing about the field in blogs, scholarly publications, or in the context of their membership in professional organizations (such as the American Library Association or Special Libraries Association). Of course, these are often the same people; however, I would propose that there is a dual consciousness dividing professionals fulfilling institutional roles and those in professional organizations. Thus, what Dimaggio suggests about art museums might also hold for libraries. As he states, “what is striking, however, is how little conflict occurred inside organizations and how much was played out at the level of the field. Professionals seem to have possessed a dual consciousness that enabled them to function as conservatives in organizational roles at the same time they used fieldwide organizations to launch attacks on the system that employed them” (268). What this amounts to in practice is often a call for innovation, creativity, and outside-the-box thinking that exists simultaneously with a whole host of bureaucratic mechanisms that maintain institutionally conservative logics that are resistant to change. While my paper will focus on recent and known examples of this dual consciousness, such as the SLA “name change” controversy, I will also explore my experiences of being a graduate student navigating a largely positivist (with some important exceptions) LIS curriculum in what I understood to be a post-positivist world. One example I will explore in my presentation focuses on how calls for scholarly innovation in LIS are met with a mix of abstract agreement and practical skepticism. Despite laying out the red carpet for Wayne Wiegand (the then co-editor of the prestigious Library Quarterly) by the heavily-endowed University of Texas’s Harry Ransom Center, many faculty at the School of Information grumbled at what they thought was a personal indictment delivered against their academic careers. Certainly, some faculty who focused on gathering pure, unmediated data did not possess a dual consciousness to the extent that they did not bother to advocate innovative approaches to library science. But many other faculty paid passing homage to Wiegand and his perceived attack on the LIS community by assigning his 1999 article, “Tunnel Vision and Blind Spots: What the Past Tells us About the Present: Reflections on the Twentieth Century History of American Librarianship” in syllabi still largely composed of the aforementioned positivist, social-scientific research (or maybe interspersed with the wisdom of evangelical Christian texts such as Habits of the High-Tech Heart: Living Virtuously in the Information Age). Consistent with Dimaggio’s observations about dual consciousness, assigning Wiegand’s essay functioned as a kind of rhetorical tribute to innovation while the bulk of the practical training focused on reproducing traditional approaches to library science. The irony is that on the macro-organizational level there may be an official endorsement of innovation (be it scholarly or otherwise), but within library institutions themselves, actors, be it staff or those in more senior positions, often replicate standard practices in opposition to those innovations and innovators hailed by professional library organizations and well-respected librarians in the field. For example, social media revolutionaries such as Chris Rasmussen and Micheal Wesch are often venerated in library circles. They are not librarians, but they are paid significant honorariums to speak at professional library and information conferences. When Wesch was invited by the Kluge Center to speak at the Library of Congress, late comers found themselves in the rare position of being chairless. Given the persistent and frequent use of the term “library automation” to refer to information technology, particularly in job announcements designed to lure the best and brightest applicants, the wide-spread interest in Wesch and his viral-video phenomenon might seem puzzling. My point here, however, is not to suggest or denounce hypocrisy as much as to understand the breakdown between individual intentions, fieldwide endorsements, and institutional practices. In Bill Drew’s Blog, “Baby Boomer Librarian,” he produced the popular post, “How to Kill a Young Librarian’s Love of Librarianship.” The post, widely linked to throughout the librarian blogosphere, in part, describes his conversation that he had with a young librarian at a SUNYLA conference: This librarian has been in a SUNY library for over 5 years. He is enthusiastic, excited, and extremely intelligent. However, the library he works in has gone through a major regression in management style over the past decade. It has gone from being a dynamic forward thinking and innovative environment to one laden with unwilling and staid librarians with a bureaucratic and fifties style organization structure. It has added many layers of middle management in the last couple of years instead of being a flat organizational model as most libraries in SUNY are striving to become. Many librarians there that used to be innovative when I first knew them 24 years ago are now protecting their turf and working on maintaining the status quo. The worst part of it is that librarians there do not even recognize what has happened. Drew follows the conversation with his often republished “list of how to kill a young librarian's love of librarianship.” My sympathy for the list and post is shared by many librarians of all ages, and I do have certain prescriptive goals for integrating innovation into librarianship. However, by drawing on the New Institutionalism, I am hoping to first understand how bureaucracies work. To this end, it is crucial to be able to explain the institutional conditions under which individual commitments to change have to face practical incentives to maintain bureaucratic order.