Identifying Fragments and Clauses

advertisement

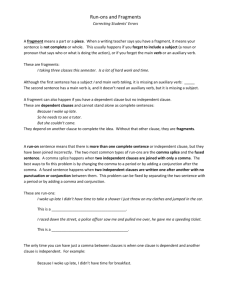

IDENTIFYING FRAGMENTS AND CLAUSES In this module, you will learn to do the following: Distinguish between sentence fragments and clauses Identify the four major causes of fragments Convert fragments into clauses Use fragments effectively. Introduction We'll look at sentence fragments and at clauses. We need to be able to identify sentence fragments and clauses because such identification is vital to our grasp of sentence punctuation. Fragments We are not concerned with complete or incomplete thoughts. Neither are we concerned with dependent or independent clauses. We are concerned only with whether or not a group of words is a clause or a fragment. So let's define what we mean by clauses and fragments. To be a clause, a group of words must contain both a subject and a verb. A fragment is a group of words that does NOT contain a subject or a verb or both. While both definitions seem straightforward enough, why is it that so many punctuation errors are committed? The answer rests in the fact that certain fragments are wrongly identified as clauses, leading to a variety of punctuation errors. So what we're going to do in the next few sections is to examine why fragments are wrongly identified as clauses. Along the way, we'll also discover methods of correcting various errors that stem from wrongly identifying fragments as clauses. The wrong identification stems from four basic causes: 1. No subjects 2. No verbs 3. Short answers 4. Added afterthoughts. No Subjects Obviously, if a group of words does not contain a subject, the group cannot be a clause. Study the following examples. Sentence: "Yesterday, walked to school in the rain." Identify the subject and the verb. We recognize the complete verb "walked." We ask: Who or what did the walking? We have no answer to the question. There is no noun or pronoun that we can identify as the doer of the action. Therefore, the sentence is not a clause, but a fragment. Correction The sentence lacks a subject, so the obvious solution is to provide a subject. "Yesterday, Margaret walked to school in the rain." The fragment has been corrected and converted into a clause by the provision of a subject. No Verbs Similar to lacking a subject, if a group of words does not contain a verb, the group cannot be a clause. Sentence: "The racer at the finish line." There is no word that we can identify as the verb in the sentence. Therefore, the sentence is not a clause, but a fragment. Correction Let's provide a verb. "The racer collapsed at the finish line." The fragment has been corrected and converted into a clause by the provision of a verb. Gerund Errors The next concept is a bit more challenging but is the concept that contributes to the majority of errors. The concept is the gerund error, a variation of the lack of verb concept. In this type of error, the writer confuses verb parts (usually present participles) for verbs. The resulting sentence often lacks a subject and part of a verb. The writer is seldom conscious of faulty sentences because they reflect normal conversation and its structure. Let's examine this concept by looking at the origin of these errors. More information about gerunds can be found in "Identifying Nouns and Adjectives" and in "Identifying Infinitives and Participles as Subjects." We'll start with a short script of normal conversation. Sally: "Have you found a job yet, Bill"? Bill: "No, and I'm really discouraged." Sally: "What's happened"? Bill: "I wasted the better part of a week. Going from one interview to another. I don't have much hope left." I think you can see Bill's faulty sentence. Mind you, such sentences are quite acceptable in conversation because the listener cannot see the periods and other punctuation marks. In addition, if you need to write dialogue for scripts, commercials, or fiction, you will have to become familiar with fragments. Let's examine Bill's faulty "sentence." Sentence: "Going from one interview to another." We recognize the participle "Going." We know that a participle can be a verb only if it has helping verbs. We search the rest of the sentence and find no helping verbs. Thus, "Going" is not a verb. There are no other words that can be verbs. Lacking a verb, the sentence cannot have a subject either. Therefore, the sentence is not a clause, but a fragment. Correction Let's provide a subject and a helping verb for the participle "Going." "I was going from one interview to another." The fragment has been corrected and converted into a clause by the provision of a subject and a helping verb to complete a verb phrase. Sentence fragments arising from the gerund error are the most common in technical and business writing. But right on the heels of the gerund error is the short-answer error. Short-answer Error Let's continue Sally and Bill's conversation to discover the second most common cause of sentence fragments. Sally: "A job will turn up." Bill: "Not in my lifetime." In Bill's statement, we recognize no word that can serve as a verb. Therefore, the sentence is not a clause, but a fragment. Let's provide a subject and a verb. "A job will not turn up in my lifetime." A subject and a verb have transformed the fragment into a clause. Added Afterthoughts The added-afterthought error is almost as common as the short-answer fragment. The main difference between the two is that the short answer is a fragment in response to another person's speech while an added afterthought is a fragment in response to your own speech. Let's clarify this by continuing Sally and Bill's conversation. Sally: "Have you tried all the convenience stores"? Bill: "I've tried them all. Except those on Maple Street." Sally's sentence and Bill's first are properly constructed as clauses, but what about Bill's last sentences? "Except those on Maple Street." His sentence lacks an action word--lacks a verb. Lacking a verb, the sentence cannot have a subject. Therefore, the sentence is not a clause, but a fragment. Comment Did you notice how in the short answer and in the added afterthought we needed to refer to the preceding sentences in order to provide a subject and/or verb for these kinds of fragments? This contextual reference is the main reason fragments go unnoticed in the course of casual conversation. While such fragments are acceptable in conversation, we cannot write in fragments as technical or business writers. But as professional writers we may find a need to mimic casual conversation in our writing. Then, of course, we will need to use fragments. When that need arises, do not construct fragments without care and thought. In this module, you learned how fragments are created and how they are corrected. Use this knowledge to construct convincing fragments when you need to use them. Exercises Select the answer that correctly identifies this group of words as either a fragment or a clause. The answers appear after the last question. 1. A dreary winter without much sun A. Fragment B. Clause 2. She was delighted A. Fragment B. Clause 3. Was always a problem for me A. Fragment B. Clause 4. The announcement reminding me A. Fragment B. Clause 5. Many young people intend to go to college A. Fragment B. Clause 6. In the room, the noisy party ending A. Fragment B. Clause 7. They will drive A. Fragment B. Clause 8. Last seen at the end of March A. Fragment B. Clause 9. It was raining cats and dogs A. Fragment B. Clause 10. Wanting to try again A. Fragment B. Clause 11. Being cold and windy A. Fragment b. Clause 12. And she had many interests A. Fragment B. Clause 13. Physics is always a problem A. Fragment B. Clause 14. About my job, for one thing A. Fragment B. Clause 15. Nevertheless, few will succeed A. Fragment B. Clause 16. The guests to bring a non-perishable food item A. Fragment B. Clause 17. But not to Winnipeg for the Grey Cup A. Fragment B. Clause 18. And coming home soon A. Fragment B. Clause 19. There were poodles in the street A. Fragment B. Clause 20. He tried his best A. Fragment B. Clause Answers 1, A. 2, B. 3, A. 4, A. 5, B. 6, A. 7, B. 8, A. 9, B. 10, A. 11, A. 12, B. 13, B. 14, A. 15, B. 16, A. 17, A. 18, A. 19, B. 20, B.