W_ Virginia Death outpacing birth

advertisement

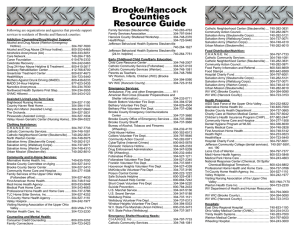

With Death Outpacing Birth, a County Slows to a Shuffle Andrea Morales for The New York Times WEIRTON, W. Va. — Life in this industrial area has slowed to a shuffle along with the steel mills that used to power it. Young people have moved away, leaving an aging population that no longer has the energy to put on street fairs or holiday parades. In fact, this community in West Virginia’s northern panhandle holds an unwelcome distinction. With just 71 babies born on average for every 100 residents who die, Brooke County, in which Weirton is partly located, has the largest such gap in the nation among counties in metropolitan areas, save for a handful of places that are magnets for retirees. (Hancock County, which contains the other part of Weirton, is in similar demographic straits.) The main reason Brooke County is so far off the national number — which is 171 births to 100 deaths — is that it has missed out on one of the dominant demographic trends to emerge from the recent census: the influx of young immigrants into communities across the United States. The median age for Hispanics, by far the largest immigrant group, is just 27, far lower than the median age for whites of 41. Without immigrants or economic opportunities to keep its younger residents close to home, Brooke County and others like it are showing their age. At St. Paul Catholic Church in Weirton, the Rev. Larry Dorsch has buried 15 people this year and baptized one. The American Legion in Wellsburg has closed because of a lack of young supporters. Volunteer fire departments are so understaffed that people come from other towns to fight fires. “You can declare a person dead, but you can’t declare a town dead,” said Daniel Guida, a lawyer in Weirton. “Some towns have energy, that spring in your collective step. We’re missing that. We need to get on with Act 2. But how?” According to Kenneth Johnson, the senior demographer at the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire, there are now 853 counties with similar population trends — “more coffins than cradles,” as he calls it — including parts of the Great Plains, the Midwest and New England. (The problem is even more acute across the Atlantic — countries in the European Union collectively will cross the threshold for having fewer births than deaths by 2015, and would only experience population growth through immigration, according to a 2009 report on aging published by the European Commission.) West Virginia is the only state in the country with more deaths than births, but other states, like Maine, are not far behind. Mr. Johnson estimates that many white areas will tip into natural decrease in the next 10 to 15 years. “This is the story of what’s happening to white America,” Mr. Johnson said. “America is built by young people. They are the backbone. But what if they are not there?” If Brooke County is a postcard from the future, it ended up there because it never adapted from its past. For decades, it was a steel manufacturing powerhouse, employing thousands of workers in mills along the Ohio River. Weirton Steel, a hulking plant that straddles Weirton’s main street (it was recently used as a set for a science fiction movie, “Super 8,” and in the 1970s for “The Deer Hunter”), was once the largest single private employer in the state. Now Wal-Mart holds that distinction, and Weirton Steel, now owned by Arcelor Mittal, a Luxembourg company run by an Indian billionaire, is a fraction of its former size. Grass grows through cracks in the vast, empty parking lots. Manufacturing jobs, long the lifeblood of the area, shrunk by 38 percent statewide since 1990. Now health care is the state’s second-largest employer after government. The number of young people here sagged with the economy. The population under 35 is about half of what it was in 1980, while the number of residents 55 or older has jumped by 23 percent, according to 2010 census data released Thursday. Now walkers and wheelchairs are more common than strollers. Sunday school classrooms at the United Methodist Church downtown are ghostly quiet, and Brooke High School has just half the number of students it did when it opened in 1969. Even funerals are drawing smaller crowds. John Greco, 46, a funeral home director in Weirton, said 50 to 60 guests attend funerals today, about half the numbers in the 1990s. Mr. Greco said 37 members of his high school graduating class moved away, compared with 16 who stayed in town. “It’s very natural now that everybody my age is gone,” said Mr. Greco, who stayed to take over his grandfather’s business. Fewer people means, inevitably, less of a sense of community. Father Dorsch spends his days looking for ways to revive it. In one town, he used public outrage about stray shopping carts to get people involved in improving their community. But Weirton has such bitterness over the mill that it has been hard to get its residents to trust anybody, and it seems stuck in place. “It’s like a clinically depressed person, who curls up on the couch and withdraws,” he said of Weirton. “It’s the hardest assignment I’ve ever had.” The demographics have created a death spiral, both literal and metaphorical. The lack of young people had reduced the tax base. With so few young people, volunteer fire departments are having trouble keeping staffing at safe levels. Greg Sheperd, 34, a volunteer at the Bethany Fire Department, said that when the alarm goes off, the trucks leave with just two people on them. Six are needed, Mr. Sheperd said, so volunteers have to come from other towns to help. His wife, Tara Sheperd, also in her 30s, said most of her colleagues at the food bank she runs in Weirton are over 50. Water cooler talk is, well, old. “I no longer think the Donut Hole is a restaurant,” Ms. Sheperd said, referring to the nickname for the gap in prescription drug coverage for the elderly that is a constant topic of conversation at work. But even one energetic young couple can do a lot to bring a town back to life, as the Sheperds have proven in Beech Bottom, the tiny town where they live. The town now has a new playground, thanks to the grant writing skills of Mr. Sheperd, who is from the county. “We need someone to help us keep the plates spinning,” Mr. Sheperd said. “There’s just not a lot of us here.”