The central conceit of this poem is to imagine life as a

advertisement

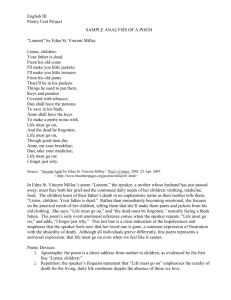

After You, Gary Cooper… A model commentary The central conceit of this poem is to imagine life as a confrontation, in the metaphorical terms of a Wild West shootout. As the title suggests, its speaker prefers to offer the dubious glory of living one’s life as a hero to someone else, specifically a Hollywood actor, whose name invokes an allusion to High Noon, his most famous cowboy role as the reluctant amateur sheriff saving a community of worthless townsfolk. INTRODUCTION The form of the poem is a kind of meditative rather than dramatic monologue, reinforced by the speaker’s conversational working out of an idea – namely, that “life … can be a bit of a bastard”. Dawe maintains this casual, man-in-the-street philosophising through the use of parenthetic phrases like “off-hand, of course”, or such informal expressions as “Personally, I’m damn glad…” The effect of this mode of address to the reader is to reinforce the speaker’s attitude of knowing reticence, a tone which supports his central idea that its better to hang back and avoid risks than speak up in bold declarative statements in the face of “an awful lot of hot lead”. Dawe’s use of diction skilfully combines a plethora of references to the culture of Hollywood westerns – “Main Street’; “Boot Hill”; “Colt forty-five” – with the self-effacing slang of an Australian idiom – “a long shade of odds”; “safely out of earshot”; “a bit of a bastard” – as well as the more contemporary language of our risk conscious urban world – “the basic formula”; “insurance premiums”; “a marked deficiency”. The poem’s success in fact lies in the way Dawe has managed to integrate these three different language types into a single voice, while still taking advantage of their unique qualities. The laconic Australian slang punctuates with irony what are in fact three quite long-winded sentences, setting off not only the intellectual tone of “this awkward proposition” but also the inflated Hollywood machismo of “packed on the hip, butt out, with trigger tied back like a Colt forty-five”. The latter metaphor(mula) beautifully expresses this also through its punchy rhythm and coarse alliterative monosyllables that almost cry out for an American cowboy’s accent. But this macho rhythmic pattern doesn’t awkwardly intrude, despite the use of hyphenated punctuation to insert it in the sentence. Its alliteration is prepared for in the more elongated phrasing that precedes it, with the blend of repeated ‘b’, ‘h’ and ‘f’ sounds. EXPOSITION The use of imagery, like the poem’s rhythm and diction, is smoothly incorporated into the speaker’s overall argument that life is a little more complex and risky than a Hollywood western. Personifying Life as “that taciturn hero with the steel-blue eye” and characterising its ‘solution’ as a metaphorical gunslinger’s trusty weapon, Dawe suggests that representations of life as a heroic confrontation between the individual and fate are dangerous oversimplifications. Even the ironic qualification of the ‘hero’ as something less than mythical in his prowess – “certainly not chain-lightning on the draw” – deftly marries the proverbial notion of life’s tediousness with its ability to surprise “once he does clear leather”. The final stanza picks up the extended metaphor of the traditional “dusty Main Street” shoot out, while reminding us that it comes from Hollywood stereotypes – “Ranch Night at the local theatre”. Although the speaker clearly emphasizes an ironic desire for anonymity, preferring to take life “from around the nearest corner” rather than on “parade”, two statements seem to bear the fuller weight of the poem’s impact. His intention to “let Life have it where it’ll do most good” is immediately followed by the corner reference, implying that the “most good” in life is to be found around it, not in the Main Street. But the proper sense of the sentence is that the “most good” refers to where Life ‘gets it’, not where we are when we ‘dish it out’. However, the ambiguity is surely intentional and the best interpretation seems to be that we won’t find the most good in life by imitating Hollywood stereotypes of heroism. The poem’s final line reinforces this with its implication of short-lived fame and vanity, where “for the sake of looking good” life is reduced to “twenty gunsmoke-glorious seconds…” imagery = key terms monologue = other important technical terms CONCLUSION After You, Gary Cooper… 5 10 15 20 25 30 One of the main things I would say (off-hand, of course) about this awkward proposition known as Life, is that it can be a bit of a bastard if you don't happen to have the basic formula for facing it ready to hand – packed on the hip, butt out, with trigger tied back like a Colt forty-five – and your insurance premiums paid up. Particularly since Life, that taciturn hero with the steel-blue eye, though certainly not chain-lightening on the draw, can usually overcome what bystanders, if safely out of earshot, might call a marked deficiency by pumping an awful lot of hot lead in your general direction once he does clear leather. Personally, I'm damn glad I won't ever be any closer To the old Wild West than Ranch Night at the local theatre, because I'd a hell of a lot sooner let Life have it where it'll do most good from around the nearest corner, than parade the dusty Main Street of some anonymous cow-town, taking a long shade of odds on a one-way trip to Boot Hill, just for the sake of looking good for twenty gunsmoke-glorious seconds… Bruce Dawe