The art of Katherine Mansfield`s short stories

advertisement

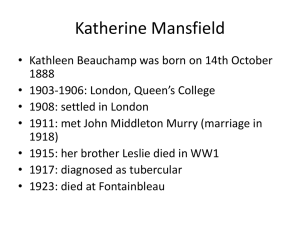

The art of Katherine Mansfield’s short stories Katherine Mansfield was one of the most famous women writers in the early 20th century. In some sense, she was also the real founder of the literary of the New Zealand nation. She was born in Wellington, New Zealand in Oct. 1888. At the age of 14 she went to London to study at Queen’s College. During the three years of studies she often wrote short stories for the college journal. As she was dissatisfied with the dull and leisured life of her family. She went to London again in 1908 and determined on writing as her career. Since then she lively mostly in England. In 1923 she died of tuberculosis in France. During her short 35 years of life, she had written some poems, literature comment, and also translated the Russian writer Anton Chekhov’s works, but what really established her fame as a prominent writer were her short stories. It had been a tradition in English literature that short story, as a short literary form, was often overlooked by people. James Joyce, Mansfield’s contemporary, was not accepted by people in England when his short story collection “Dubliners” came out. D. H. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, and many other contemporaries, achieved their success by long novels. But Katherine Mansfield managed to establish her reputation by short stories only. She dedicated her whole life to this literary type, left behind us rare art treasure. Mansfield’s short stories showed great ingenuity. She drew materials from her own experience, chose trifles as her subjects. Her theme was confined but significant to life: the growth and self-consciousness of the female; the relation between men and women; children’s innocence and the cruelty of the reality. She pursued high writing techniques, the four of which were: description of details; more atmosphere than plot and the perfect blend of feeling and setting; interior monologue; symbol. Her language was written in a prose style spiced with poetic flavour. There is a tradition lies in the creation of fictions in English literature: The writer often gathered materials from his own early or past experience. “Katherine Mansfield never wrote things that were not experienced by herself. Every thing in her fiction, undoubtedly, were based on her own experience.”1 Most of Mansfield’s subjects were recollections of her family and her childhood spent in New Zealand. In her total less than a hundred articles, about 60 were at the background of New Zealand. Choosing trifles as subjects was also the similarity among women writers. Jane Austin’s fiction plot originated from several families in the country. Katherine Mansfield’s plot seemed to develop in narrower surrounding which was not conspicuous: one family, subtle relations among a few family members, etc. So the theme she discussed in her fictions was not grand or extensive. They were mainly confined in these aspects: the growth and self-consciousness of the female; the relation between men and women; children’s innocence and the cruelty of the reality. There were a series of female characters in Mansfield’s stories. Rosabel in “The tiredness of Rosabel” was a teenager. She viewed the complicated world with her innocent and childish eyesight. The young women appeared in “Miss Brill” and “Picture”. Their ideals always conflict of the reality. Ma Parker in “The life of Ma Parker” was a representative of the old women, who had experience the happiness and hardship of life, the understanding and estrangement of human world, the beauty and ugliness, joy and suffering. Mansfield wrote not many stories about men and women. In these stories, the writer mixed into her own misfortune with men and drew this conclusion: man and woman won’t have happy and satisfactory endings because woman is always the sacrifice of cold and domineering man. “The little Governess”, “The Flower”, “The man without a temperament” “Jene Parle Pas Francais” belong to this kind. Stories on children constitute half of her total creation. To a great extent, they were based on the writer’s recollections of her own childhood. In such stories, she discussed the subtle relationship that was simple but hard to understand between children and children, children and adults. “Sixpence” described the punishment and forgiveness of the father to the child. “Her first ball” depicted the first association of the girl with the adult society. “At the bay” wrote one day the children spent with the whole family in a seaside villa. In “The garden party”, the children touched the dark side of society at the first time. “The doll’s house” showed us the influence of the social class on children. Mansfield described the children’s inner world vividly, exquisitely and acutely. Her New Zealand stories on children account for the most important part of her contributions to art. Though the materials were not extensive, the theme was confined, Katherine Mansfield expressed her love and hatred. To express the theme explicitly, she used very high writing technique. One of which worth mentioning is her description of details. Mansfield laid stress on describing details, she regarded details as “the lives in life”. But it’s not easy to explore “the lives in life” since not all common trifles had this feature. It must have something fresh, something attractive on itself. The writer’s observation must be sharp so that he could capture it from the kaleidoscopic life. Katherine Mansfield had an uncommon ability of this kind. In “Sun and Moon”, before the dinner, Sun and Moon saw a table of beautifully furnished food. They were even joyful when they saw a plate of ice pudding in the refrigeration. “It was a little house. It was a little pink house with white snow on the roof and green windows and a brown door and stuck in the door there was a nut for a handle”. They went to the dining--room. They were almost frightened. “…all the lights were red roses. Red ribbons and bunches of roses tied up the table at the corners. In the middle was a lake with rose petals floating on it. “That’s where the ice pudding is to be,” said cook. Two silver lions with wings had fruit on their backs, and the salt cellars were tiny birds drinking out of basins. And all the winking glasses and shinning plates and sparkling knives and forks—and all the food. And the little red table napkins made into roses…” These descriptions of details displayed the children’s fairyland, their illusion. But when the children went back to the beautiful dining— room after dinner, “Oh! Oh! What had happened. The ribbons and the roses were all pulled untied. The little red table napkins lay on the floor, all the shining plates were dirty and all the winking glasses. The lovely food that the man had trimmed was all thrown about, and there were bones and bits and fruit peel and shells everywhere. There was even a bottle lying down with stuff coming out of it on to the clothe and nobody stood it up again. And the little pink house with the snow roof and the green windows was broken—broken—half melted away in the centre of the table.” “I think it’s horrid—horrid—horrid!” Sun sobbed.” The child’s illusion had been destroyed. “wailing loudly, Sun stumped off to the nursery!” These vivid descriptions of details, under the writer’s ingenious arrangement, gave readers intense artistic appeal. Katherine Mansfield’s short stories had the characteristic of impressionism. It did not stress on the dramatization of the story or the completeness of the plot, but concerned more on atmosphere and the expressing of feelings. Her plot was rather simple and sometime there’s hardly any plot. While reading her stories, we always just can’t tell what the story was like, what we remembered deeply was the atmosphere and feelings in the story, and the sense we experienced. In her story emotion and scene were blended happily to reach an artistic conception, her own poetic artistic conception. Mansfield’s “The first ball” described the mood of a girl, Lira, when she at the first time took part in a ball. Literally, Mansfield described nothing else except the simple conditions of what lira saw in the ball and her mood. “If we ask when the ball begin, lira thought it was hard to answer.” It began when she sat down in the carriage. In fact, it began when she made up at home. How excited she was! She was so excited that she almost dared not go to the ball. While dancing “an old experienced man” make her realize that the first ball was but the beginning of the last ball, she was depressed. Just for politeness, she had to accept another invitation to dance, but at once she got excited again. She couldn’t recognize “the veteran” who woke her up. The story ended in lira’s cheerful dance. The story was ended, but the atmosphere created by lira’s change of emotion still affected readers. Isn’t the life so? Clearly knowing the first ball was but the beginning of the last ball, we still wait for it cheerfully. It’s natural, and it should be. Mansfield was also good at describing scene. Her another short story “At the bay” drew materials form her retrospection of the early life in New Zealand. One and another single parts which were segmented each other constituted a complete picture of a day’s life. It showed the life’s rhythm and tone from day to night of a very representative New Zealand family. With her keen observation, the writer depicted every small picture. In this story, before the main characters appeared the writer cost several paragraphs on depicting the beautiful scenery of the early morning. The light mist at the bay, the dew on the flowers and grass, the breeze, the singing bird, the sheep flock, the herder and his dog. It’s like a piece of delicate water-color picture, a soft song. The scene she described was the real objective scene in eyesight, meantime, was the imaginative scene in heart. The relation of the two was that of interweave of the scene and the character’s inner activities. Only by so, the moving effect of the blend of feeling and setting can be achieved. Mansfield never wrote scenes alone. She poured her own emotion into the description of the bay. At the beginning of “The wind blows”, a sad atmosphere caught us at once. “Suddenly—dreadfully-she wakes up. What has happened? Something dreadful has happened. No—nothing has happened. It is only the wind shaking the house, rattling the windows, banging a piece of iron on the roof and making her bed tremble. Leaves flutter past the window, up and away; down in the avenue a whole newspaper wags in the air like a lost kite and falls, spiked on a pine tree. It is old. Summer is over—it is autumn—everything is ugly….” Then the tone became more sorrow. “In waves, in clouds, in big round whirls the dust comes stinging, and with it little bits of straw and chaff and manure. There is a loud roaring sound from the trees in the gardens, and standing at the bottom of the road outside Mr Bullen’s gate she can hear the sea sob: “Ah!….Ah!….Ah-h!”. In the last part of this story, the brother and sister went for a walk round the esplanade. “It’s getting very dark. In the habour the coal hulks show two lights—one high on a mast, and one form the stern” “A big black steamer with a long loop of smoke streaming, with the portholes lighted, with lights everywhere, is putting out to sea. The wind does not stop her; she cuts through the waves, making for the open gate between the pointed rocks that leads to…It’s the light that makes her look so awfully beautiful and mysterious…They are on board leaning over the rail arm in arm.” “Now the dark stretches a wing over the tumbling water. They can’t see those two any more. Goodbye, goodbye. Don’t forget…But the ship is gone, now. The wind—the wind.” By means of the description of the scene, the writer’s endless mourning for her beloved brother Chummie, Bogey in this story, deeply moved reader’s heart. Katherine Mansfield was also a pioneer in the interior monologue, which her contemporaries James Joyce and Virginia Woolf developed in their works as stream-of-consciousness technique. She did her utmost to present the character’s interior world, and she tried her best to capture the moment when human’s heart had a sudden consciousness of life and oneself. The creation principle she obeyed all her life was to “melt into the character”. She considered she must be the thing itself before describing and re-creating one thing. “When I described duck, I swear, I’m also a white duck with round eyes swimming in the yellow foam bubbling pool, occasionally having a quick glimpse of my inverted reflection in water.”2 When she wrote “The stranger” she felt as if she had stood in the port and waited for several hours herself. When writing “The journey” she became “Valena, hanging the swan-necked umbrella”. In Mansfield’s works, the writer never appeared as a narrator, but completely melt into the heart of the character she created, thought in their intonations and ways. In “The little governess”, the writer adopted a pure childish girl’s feeling and sight to observe and experience the surrounding world. The first sentence in the story “Oh, dear, how she wished that it wasn’t nighttime. She’d have much rather travelled by day, much much rather.” vividly transmitted a young girl’s speaking manner and psychology. Towards the rude porter she met in the station, she affirmed: “He is a robber!” The old man in the train was “Ninety at least”. Just by a few words, the writer sketched a girl’s knowledge and tone. In the girl’s eye, “fat, fat coachmen driving fat cabs”, “a policeman standing in the middle like a clockwork doll”… All these soaked a child’s childishness and liveliness, a childish heart was expressed so vividly, cordially and movingly. “The canary” is an excellent example of her using interior monologue technique. The character was a lonely woman, only a lovely canary accompanied her all day. The whole story is her interior monologue she spoke to the bird case after the bird died. The character loved the canary so sincerely and intensively that only the bird’s song can give her some comfort when she felt lonely. When the canary sang, she felt working is also enjoyable. Through the inner monologue a person living in the hostile world appeared before our eyes. “Miss Brill” narrates one day the spinster, Miss Brill spent in the park. Sitting in the park and observing people at weekends is the only happy thing in her tedious, lonely life. That day she wore her leather scarf specially and went to the park as usual, she sat on her usual bench and observing coming and going people happily to enjoy her long-expected time. But a couple of young men abused her just for her existence. She realized suddenly that she was ugly and unwelcome. When she put her scarf back into the box, she heard something crying. —That’s her heart crying. Here the inner monologue is used to explore the character’s inner world, and the deep consciousness of the essence of life is perceived. The artistic technique of symbol is also Mansfield’s favourite. In Mansfield’s stories we can find many details she described had their symbol meaning besides narration. The ice pudding in “Sun and Moon” symbolized children’s illusion to life. Although the pudding house is lovely and beautiful, it’s food for people to eat, so the ice pudding also indicates Sun’s disillusion is unavoidable. Bertha Young, the heroine in “Bliss”, was always intoxicated with the bliss of her family. In her garden, “there was a tall, slender pear tree in fullest, richest bloom; it stood perfect, as though becalmed against the jade-green sky…it had not a single bud or a faded petal.” “And she seemed to see on her eyelids the lovely pear tree with its wide open blossoms as a symbol of her own life.” But one day she found unwittingly her husband and her girl friend betrayed her. Her feeling of bliss disappeared completely. She cried: “what is going to happen now?” But “the pear tree was as lovely as ever and as full of flower and as still.” It deepened her agony. The pear tree, once the symbol of the illusion of the beauty of life, finally turned into the symbol of darkness, ugliness and deception. Katherine Mansfield spared no effect in pursuing writing techniques. She was rigorous in her creative work, carefully and strictly choosing every word, every sentence, revising each story again and again until she was satisfied. In a letter to John Mury3 she said she would rather rewrite the whole article just for one word. Due to her hard work, the words under her pen seemed to have some magic power, they can arouse your vision, your hearing, your smelling and touch… She wanted “At the bay” to have some fish-like smell.4 “Turkish bath” to have a “wet, damp, soft like mud feeling”.5 When she wrote “Miss Brill”, she chose not only the length of each sentence, but also the rhyme and rhythm of each sentence. “I also deliberate the ups and downs of each paragraph. This is to coincide with her, at the special time on that day, I read it aloud after I finished—for many times—like a man playing instrument, tried to get nearer and nearer to the behaviour of Miss Brill until it coincides.”6 By means of her intelligence and diligence, her language had the elegance of prose and the conciseness of poem. In “Prelude”, Scene 5, the writer described the natural beauty of her homeland like these: “Down came sharp and chill with red clouds on a faint green sky and drops of water on every leaf and blade. A breeze blew over the garden, dropping dew and dropping petals, shivered over the drenched paddocks, and was lost in the sombre bush. In the sky some tiny stars floated for a moment and then they were gone—they were dissolved like bubbles. And plain to be heard in the early quiet was the sound of the creek in the paddock running over the brown stones, running in and out of the sandy hollows, hiding under dumps of dark berry bushes, spilling into a swamp of yellow water flowers and cresses.” From these words we could smell the fragrance of flowers, the sound of water, and as the writer wished, we are deeply touched by the poetic language. Mansfield’s lifetime was full of frustrations: the unhappy first marriage, the loss of her beloved brother and the torment of disease etc. But she threw herself into the short-story writing with love and passion. Her creation works showed that English short story, as an art form on its own, proceeded to its mature stage in England in the early 20th century. It got rid of the traditional pattern of story narration plus sermon, strode into the era of revealing the world by sketching inner spirits. As early as in 1927, her short stories were translated into Chinese by the famous poet Xu Zhimo. The poet sang highly of her. In his eyes, Mansfield’s figure represented the delicate and elegant feminine image. In his elegy to Mansfield, he described her death as “bright shining tear dropped from the sky.”7 NOTES 1. Gordon,Ian: Katherine Mansfield; Macmillan 2. Letter to Blaite on Oct. 11. 1917 3. Letter to John Mury on Oct. 11.1920 4. Letter to Blaite on Aug. 8. 1921 London: 5. Mansfield, Katherine:Diary on Nov. 21 1921 6. Letter to Richard Mury: Jan. 17 1921 Xu Zhimo: Line 2;Elegy to Mansfield