Women and Madness in Literature

advertisement

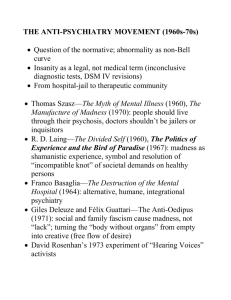

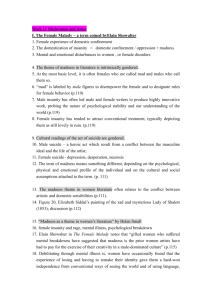

BTAN2104MA; Code: 07 ADVANCED TOPICS: WOMEN AND MADNESS IN FILM AND LITERATURE MA seminar; 5 credits Thu 14-15.40 Rm 109. SÉLLEI NÓRA OFFICE: 116/4 OFFICE HOURS: Wed 18.00-19.00 Thu 13.00-14.00 sellei.nora@arts.unideb.hu Designed to be interdisciplinary, the course offers to address the issue how the image of madness serves multiple purposes in works of English, Scottish, Canadian and New Zealand literature in the 20th century, how the term madness and the discursive construction of the term “madness” basically serve the purposes of, and perpetuate, the dominant patriarchal power structure. By relying on Freudian, Foucauldian, Laingian and feminist theories of madness (with a special emphasis on hysteria), the course intends to bring to the surface the implications of the prevalent discourses of madness in the past two hundred years, and to examine their interconnectedness with literary representations: not only how stories of madness reflect the power structure but also the way how madness may function as a subversive discourse in some literary texts, including the analysis of theories contesting the subversive potential of madness. The major goal of the course is to introduce students into the interdisciplinarity implied in this complex area, to make students gain insight into the interconnectedness of discursive theories of madness and gender (more specifically the discursive formation of women’s madness), and the question of literary and theoretical representations of women and madness by reading texts of both kinds. By reading theoretical texts, students will develop their understanding of how theories and terminologies are underpinned by preliminaries and presuppositions. By reading texts, however, students will create an awareness of how such concepts as madness can be exploited both in repressive and subversive ways in textual representations. The course is open for both for 1st- and 2nd year MA students, but both in terms of schedule and grading their syllabus is different. Watch out for the details appropriate in your case. Course requirements Presence at classes: no more than three absences are allowed. Each 100-minute slot counts as one presence or absence. In the case of a longer absence (either due to illness, or official leave), the tutor and the student will come to an agreement of how to solve the problem. Reader’s journal: the student is expected to keep a reader’s journal in a separate notebook, recording opinions, impressions, raising questions. The journals are to be in class, and to be used for facilitating discussions. Participation in classroom discussion: the student is expected to take an active part in classroom discussions. This activity contributes to the seminar grade. (The reader’s journal can be of great help in this respect.) The seminar format and the 1 reading requirements suppose that the assigned text(s) should be read for the class. Tests on the assigned readings can be expected at each seminar. The result of these tests contributes to the seminar grade (one “minor test” per discussion session: 12%). If you do not achieve 66% of the maximum score of such tests, your seminar is a failure (the grade is a one). You’ll be granted, though, one chance to make up for the failure of these minor tests at the end of the term as agreed with your course tutor. Required criticism and presentations: a ten to fifteen minutes’ student’s presentation on the most important ideas and points of an essay chosen by the student is to be given. Each student is expected to have either an individual or joint presentation in the course of the term. The presentation is an integral part of the course assignment, and will be duly assessed. Apart from this, the essays of criticism are highly recommended to read for everybody as the main points must be remembered and will be tested on in the final test. For your presentations, sign up on the students’ forum on the institute website (main topic: “Brit MA”). End-term test: an objective (and creative?) test on what is covered during the term. Only for 1st-year MA students: Term essay (research paper): the student is expected to write a take-home essay of about 2,000 to 2,200 words, related to the course in its approach and thematic concerns (40%). The essay must be written in the form of a research paper. Secondary reading and scholarly documentation, conforming to the requirements of the MLA Style Sheet, are required (MLA style sheets and handbooks are available in the department library). In their research papers students are required to cite at least five proper academic sources like books, book chapters and/or journal articles of academic standard, that is, referenced secondary material should either be borrowed from the library or downloaded from an online database that meets scholarly requirements (such as JSTOR, EBSCO or Arts and Humanities Full Text [ProQuest]). Quotes taken from printed or online sources such as Wikipedia, Enotes, York Notes, etc. will NOT be accepted as relevant secondary material. Plagiarism and academic dishonesty will be penalised as described in the Academic Handbook of the Institute (see also below). The essay is to be submitted by the defined deadline, otherwise the grade will be lowered (see below). The essay will only be accepted in a worprocessed (typed) format. The cover sheet of the essay must contain th following statement: “Hereby,I certify that the essay conforms to international copyright and plagiarism rules and regulations,” and also the signature of the student. Please note that each and every course component above is obligatory: the failure to meet any of these requirements (class attendance, small tests, presentation, home essay/research paper, end-term test) will jeopardise the completion of the course. Out of three course components – small tests, research paper/essay submission, endterm test – only one re-sit or re-submission will be granted; failure to meet more than one requirement will automatically result in overall failure. Please also note 2 that there is no make-up for insufficient class attendance, presentation or in case you fail to submit your research paper (term essay) by the defined deadline. Research paper style-sheet: for simple page references use brackets in the body of the text; use notes only if you mean to add information that would seem a deviation in the text; sample references in brackets: (Smith 65); if there are several works by the same author choose a key word of the title of the book: (Smith, Good 65), or if it is an article: (Smith, “Further” 65). sample bibliography entry: referring to books: Smith, John. Good Ideas. Place: Publisher, Year. referring to articles, poems, etc.: in volumes: Smith, John. “Further Good Ideas”. Editor of volume (if relevant). Volume Title. Place: Publisher, Year. in journals: Smith, John. “Further Good Ideas”. Title of Journal 2.4 (1996): pages. Plagiarism and its consequences Students must be aware that plagiarism is a crime which has its due consequences. The possible forms of plagiarism: 1. word by word quotes from a source used as if they were one’s own ideas, without quotation marks and without identifying the sources; 2. ideas taken from a source, paraphrased in the research paper writer’s own words and used as if they were his/her own ideas, without identifying and properly documenting the source. Plagiarism, depending on its seriousness and frequency, will be penalised in the following ways: 1. The percentage of the submitted paper will be reduced. 2. The research paper will have to be rewritten and resubmitted. 3. In a serious case, this kind of academic dishonesty will result in a failure. 4. In a recurring, and serious case, the student will be expelled from the English major programme. Late submission policy 1. Deadlines must be observed and taken seriously; 2. The research paper submitted more than six weeks later than the deadline cannot be considered for course work; 3. The research paper submitted in less than six weeks after the deadline will be penalised by a reduction in the percentage (the extent of the reduction is defined below: see “Grading Policy”); 4. In exceptional and well-documented cases, the extension of deadlines can be requested of (negotiated with) the course tutor well in advance (definitely not after, or on the day of, the deadline). 5. If you submit your essay after the first (and before the final) deadline, proceed in the following way: a. either submit it in person to your course tutor 3 b. or give it to any member of staff of IEAS, asking him/her to write the precise time of submission on the cover page; to sign the submission time; and to put the essay either in my postbox in Rm 111/1 or on my desk in 116/4. NEVER put essays in the box in the corridor, and certainly not without a colleague’s signature and indication of submission time! c. if you finish your paper at the weekend, end Monday submission would matter from the point of view of how many points you would lose due to late submission, you are allowed to submit your research paper electronically, but even in that case, you have to submit your hard copy on the first working day; in this case, the cover of your paper must contain yet another declaration: “Hereby I declare that the electronically submitted version and the hard copy fully match each other.” Assessment of the Research Papers The research papers must have a clear statement of theme, preferably in the form of a thesis paragraph, and all the further statements must be related to this central topic or question. The text (arguments, agreements and disagreements) must be organised coherently so that the point you make and your flow of thoughts must be clear for the reader. The research papers must, naturally, be finished with a well articulated conclusion which is supposed to be the culmination of your proposed arguments. The research papers will be assessed on the basis of the following criteria: the articulateness of the thesis of the paper; the clarity of the position you take; the quality of the arguments; the use and integration of your secondary sources into the research paper; the coherence of the structure; scholarly documentation; the level of your language. The research papers will not be evaluated on the basis of what your tutor’s position is in a certain (and often controversial) issue, so feel free to elaborate your own ideas—but do it in a sophisticated way. Grading Policy 1st-year students: GRADING POLICY classroom work minor tests presentation test research paper total 18% 10% 12% 25% 35% 100% Research paper evaluation Statement of thesis Quality of argument Coherence of structure Scholarly documentation Level of language Total 5 10 10 5 5 35 4 Research paper late submission reduction Delay (days) 1–2 3–5 6–9 10–14 Reduction 2 5 10 15 Percentage 87–100 75–86 63–74 51–62 0–50 Grade 5 4 3 2 1 Grades 2nd-year students: GRADING POLICY classroom work minor tests presentation test total 20% 10% 20% 50% 100% Grades Percentage 87–100 75–86 63–74 51–62 0–50 Grade 5 4 3 2 1 Texts: Primary texts (novels): available in the Institute Library Secondary texts: available in the Institute Library in various volumes and/or in the course packet Women and Madness in Literature; Foucault’s Madness and Civilization is also available in multiple copies (handed out by the course tutor), and will most probably be shared, depending on the number of students doing the course. Course Details Week 1 (18.02.): Orientation and introduction to the course Week 2. (25.02.): Question: How has the concept of madness come about? Has it always been with us? This seminar will function as a preliminary theoretical introduction to the course based on Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilization, and will focus on the historical and discursive formation of madness, while it will also address the question of women and gender. Required reading: Foucault, Michel. chs: “The New Division”; “The Birth of the Asylum”; “Conclusion”. from Madness and Civilization, pp. 221-289. Showalter, Elaine. “The Female Malady”. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830–1980. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987. 1–20. Week 3. (03.03.): Diagnosing Women’s Madness Question: How is any deviance in women’s behaviour percieved and labelled? 5 The session will explore the emergence of various diagnoses and their treatment in an institutional framework, no matter how humane-looking, and the various responses to repressive power systems, and we will also compare the textual and cinametic representations: how they use (or do not use) the iconography of madness. Required reading and viewing: Susanna Kaysen. Girl, Interrupted (novel and film – to be viewed individually at home) For presentation: Ussher, Jane. “Madness and Misogyny: My Mother and Myself” and “Misogyny”. Women’s Madness: Misogyny or Mental Illness. Amhurst: U of Massachusetts Pr., 1991. 3–41. Busfield, Joan. “Biological Origins”. Men, Women, and Madness: Understanding Gender and Mental Disorder. London: Macmillan, 1996. 143–165. Week 4. (10.03.) Freud and Hysteria (or Freud’s Hysteria?); Question: Whose hysteria is it? What is (called) hysteria? Why is it hysteria that symbolises the repression of women in the Victorian period? How did the famous and infamous treatment of women: the rest cure function? The required reading for the seminar will be Freud’s Dora, a case history that has been a staple in feminist studies. By reading both the original Freudian text, and in the form of presentations some of its critiques (by Steven Marcus, Toril Moi, and Juliet Mitchell), we will analyse the dynamics of narrative and the narrative transference between analyst and patient, and will look for the connections between hysterical symptoms (or suffering, or repression) and symbolic language. Reading: Freud, Sigmund. “Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria”. Case Histories I (‘Dora’ and ‘Little Hans’). Trans. Alix & James Strachey. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977. 35–164. Week 5. (17.03.) The visual representation of a case study of hysteria: Question: The questions addressed to the cinematic text will be the same as addressed to Freud’s analysis of “Dora”, but a major aspect of discussion will be also the iconicity of women’s madness in visual representation. Required film viewing at home: Dangerous Method (copies made available in the library) Week 6. (24.03.) Revisiting Hysteria: New Perspectives (in the form of presentations) The Rest Cure: Rest and Cure? Question: How did the famous-infamous rest cure function? What was the psychosocial context behind it? How did the social structure and social assumptions regarding women’s role have an impact on the treatment? Hysteria, neurasthenia, postpartum depression, and other kinds of mental diseases, particularly if women were involved, were treated by Weir S. Mitchell by applying the 6 rest cure, which meant that women were parctically deprived of any activity, and were rendered into a state of infantilisation (including spoonfeeding by the nurse, etc.). We will raise questions of agency, speech, women’s creation, and the symbolisation of patriarchal repression from which madness is just a partial—and rather dubious—escape (you can utilise some of your previous readings like “The Yellow Wallpaper”). Reading: Bassuk L. Ellen. “The Rest Cure: Repetition or Resolution of Victorian Women’s Conflict”. Ed. Susan Rubin Suleiman. The Female Body in Western Culture: Contemporary Perspectives. Cambridge. Mass.: Harvard UP, 1985. 139–151. For presentation: Marcus, Steven. “Freud and Dora: Story, History, Case History”. Bernheimer, Charles & Claire Cahane, eds. In Dora’s Case: Freud – Hysteria – Feminism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. 56–91.a Moi, Toril. “Representation of Patriarchy: Sexuality and Epistemology in Freud’s Dora”. Bernheimer, Charles & Claire Cahane, eds. In Dora’s Case: Freud – Hysteria – Feminism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. 181–199. Mitchell, Juliet. “From Hysteria to Motherhood: The Hysterical Woman or Hysteria Feminized”. Mad Men and Medusas: Reclaiming Hysteria and the Effects of Sibling Relations on the Human Condition. London: Allen Lane & Penguin, 2000. 186–202. White, Allon. “Hysteria and the End of Carnival: Festivity and Bourgeois Neurosis”. Eds. Nancy Armstrong & Leonard Tennenhouse. The Violence of Representation – Literature and the History of Violence. London: Routledge, 1989. 157–170. Week 7. (31.03): Consultation week: no class Week 8: (07.04) The Gender of Madness or Can the Madwoman Speak? Questions: How are gender/women and madness related? What are the causes for the overrepresentation of women in mental asylums and hospitals? Can the madwoman speak? Since in Foucault there is hardly any mention of women and madness, or the gender of madness (a stance of the feminist critique of Foucault), this seminar aims to explore the interconnectedness between the concept and the construction of women, of the feminine and femininity and what is called and discursively constructed as madness in the past two centuries. The seminar, however, will also go back to the issue of witches and witchcraft, and will posit it as a previous construction of women as “deviant” and “uncontrollable”. These diverse concepts of women’s “madness” will be explored in a format dominated by students’ presentations chosen form the pool of recommended readings. For session 6, students will also read Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water as a required reading. This autobiographical novel provides the opportunity to explore the question whether women’s madness can be read as a subversive discourse that has the potentials to overturn the dominant (patriarchal) discourse. Whereas the previous seminar had presentations of articles which celebrate madness as resistance and subversion, this seminar discussion will revolve around the question of agency and subjectivity (in the 7 Foucauldian sense), and the question of the speaking subject. This discussion will be underpinned by two theoretical articles (see: Reading) which question the subversivity of women’s madness, and which will be introduced in the form of students’ presentations. Reading: Frame, Janet. Faces in the Water For presentation: Felman, Shoshana. “Women and Madness: The Critical Fallacy”. Eds. Catherine Belsey & Jane Moore. The Feminist Reader – Essays in Gender and the Politics of Literary Criticism. Second Edition. London: Macmillan, 1997. 133–153. Vrettos, Athena. relevant chapters from Somatic Fictions – Imagining Illness in Victorian Culture. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford UP, 1995. Showalter, Elaine. “The Rise of the Victorian Madwoman”. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830–1980. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987. 51– 73. Caminero-Santangelo, Marta. “Emerging from the Attic”. The Madwoman Can’t Speak: Or Why Insanity is not Subversive. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1998. 1–17. Felman, Shoshana. “Women and Madness: The Critical Fallacy”. Eds. Catherine Belsey & Jane Moore. The Feminist Reader – Essays in Gender and the Politics of Literary Criticism. Second Edition. London: Macmillan, 1997. 133–153. Weeks 9 (14.04.) and 10 (21.04): The 1930s and the Domestication of the (Mad)woman Question: What happened to the Cause in the 1930s? Who is Rebecca? Can Rebecca be read as a Jane Eyre intertext? What do the differences signify? These two seminars will, again, comprise a unit since they will be devoted to the discussion of both the novel and the film version (by Alfred Hitchcock) of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. Both the film and the novel have duly become key texts of feminist literary and film criticism. We will first watch the film version (so that students can cope with this long novel for seminar 9), and will pose the question how the male gaze organises the camera eye and the film’s texture in general. In discussing the novel, we will concentrate on the question of how du Maurier’s text differs from Brontë’s Jane Eyre and in what way the story of Jane Eyre and Bertha Mason were transformed in the atmosphere of the 1930s, in “feminism’s awkward age”. Reading: Week 9 Du Maurier, Daphne. Rebecca. Chs. I–XV. But: during class: film viewing. Reading: Week 10 Du Maurier, Daphne. Rebecca. Chs. XVI–XXVII. For presentation: Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” and “Afterthoughts on ‘Visual Pleasure and narrative Cinema’”. Visual and Other Pleasures. London: Macmillan, 1989. 14–38. Gilbert, Sandra M., Susan Gubar. “A Dialogue of Self and Soul: Plain Jane’s Progress”. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale UP, 1984. 336–371. 8 Week 11. (28.04.): Schizophrenia: the Condition of Women in the 20th Century? Question: Why did schizophrenia become a 20th-century mental disease with very strong connotations of gender? Schizophrenia, first described and analysed by R.D. Laing in non-gendered terms, has become both in the number of cases and in its treatment a 20th-century equivalent of 19thcentury hysteria. The reasons for this feminisation will be explored on the basis of Margaret Atwood’s Surfacing as a primary text (also raising the question of how an ambiguous cultural identity—Canadianness—contributes to “madness”), and on the basis of students’ presentations of Laingian theory and its feminist critique by Elaine Showalter. Reading: Atwood, Margaret. Surfacing For presentation: Laing, R. D. “Ontological Insecurity”. The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969. 39–61. Laing, R. D. “The Embodied and Unembodied Self”. The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969. 65–77. Showalter, Elaine. “Women, Madness, and the Family: R.D. Laing and the Culture of Psychiatry”. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830– 1980. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987. 220–247. Week 12. (05.05): for 2nd-year students: end-term test for 1st-year students: essay week (no class); essay submission deadline: 16.00 on 5 May; at the latest (see late submission policy): by 16.00 on 19 May. Week 13. (06.05.): Anorexia—(Ad)Just the Body? Question: How does anorexia relate to female sexuality and to “the tyranny of slenderness”? Apart from schizophrenia, it is anorexia and bulimia (eating disorders in general) that seem to be the most widespread feminine mental diseases, which apparently have nothing to do with “madness”, only with the question of physical weight. As studies have explored, however, anorexia and bulimia are caused by the most primary anxiety about the female body and female sexuality, particularly in periods of transitions and change: adolescence and pregnancy. Anorexia and bulimia, on the other hand, are closely related to the anxieties and newly created repressive discurses related to women’s entrance into the public and intellectual realms. Reading Janice Galloway’s novel The Trick is to Keep Breathing and presenting some theoretical articles on anorexia, thus, can sum up and provide a conclusion for the whole course: how madness and gender are related, how the discursive formation of “femininity” contributes to women’s madness. Reading: 9 Galloway, Janice. The Trick is to Keep Breathing For presentation: Boskind-Lodahl. “Cinderella’ Stepsisters: A Feminist Pesrpective on Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 2.2 (1976): 343–356. Caskey, Noelle. “Interpreting Anorexia Nervosa”. Ed. Susan Rubin Suleiman. The Female Body in Western Culture: Contemporary Perspectives. Cambridge. Mass.: Harvard UP, 1985. 175–189. Week 14: (19.05): End-term test (and final essay submission deadline: 16.00) Evaluation: in any of my office hours following the grade registration in Neptun. You are welcome to take a look at your end-term test, and your term essay will even be returned to you. FURTHER RECOMMENDED READING All: available in the Institute Library Benjamin, Marina. Science and Sensibility: Gender and Scientific Enquiry 1780–1945. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991. Bernheimer, Charles & Claire Cahane, eds. In Dora’s Case: Freud – Hysteria – Feminism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990. Bronfen, Elisabeth. The Knotted Subject: Hysteria and its Discontents. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1998. Busfield, Joan. Men, Women and Madness: Understanding Gender and Mental Disorder. Macmillan 1996. David-Ménard, Monique. Hysteria from Freud to Lacan: Body and Language in Psychoanalysis. Trans. Catherine Porter. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1989. Ender, Evelyne. Sexing the Mind: Nineteenth-Century Fictions of Hysteria. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1995. Foucault, Michel. Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. [1965] Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Vintage, 1988. Freud, Sigmund. Case Histories I (‘Dora’ and ‘Little Hans’). Trans. Alix & James Strachey. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977. Freud, Sigmund, Joseph Breuer. Studies on Hysteria. Trans. Alix & James Strachey. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974. Gilbert, Sandra M., Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven, Yale UP, 1984. Laing, R. D. The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969. Matus, Jill L. Unstable Bodies: Victorian Representations of Sexuality and Maternity. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1995. Mellor, Philip A. Chris Shilling. Re-forming the Body: Religion, Community and Modernity. London: Sage, 1997. Purkiss, Diane. The Witch in History: Early Modern and Twentieth-Cnetury Representations. London: Routledge, 1996. 10 Rigney, Barbara Hill. Madness and Sexual Politics in the Feminist Novel: Studies in Brontë, Woolf, Lessing, and Atwood. Madison, Wisc.: U of Wiscinsin P, 1978. Showalter, Elaine. The Female Malady: Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830– 1980. Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1985. Suleiman, Susan Rubin, ed. The Female Body in Western Culture – Contemporary Perspectives. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1985. Ussher, Jane. Body Talk: The Material and Discursive Regulation of Sexuality, Madness and Reproduction. London: Routledge, 1997. Vrettos, Athena. Somatic Fictions – Imagining Illness in Victorian Culture. Stanford, Cal.: Stanford UP, 1995. Wright, Elizabeth, ed. Feminism and Psychoanalysis: A Critical Dictionary. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992. 11