YOS 6 108

advertisement

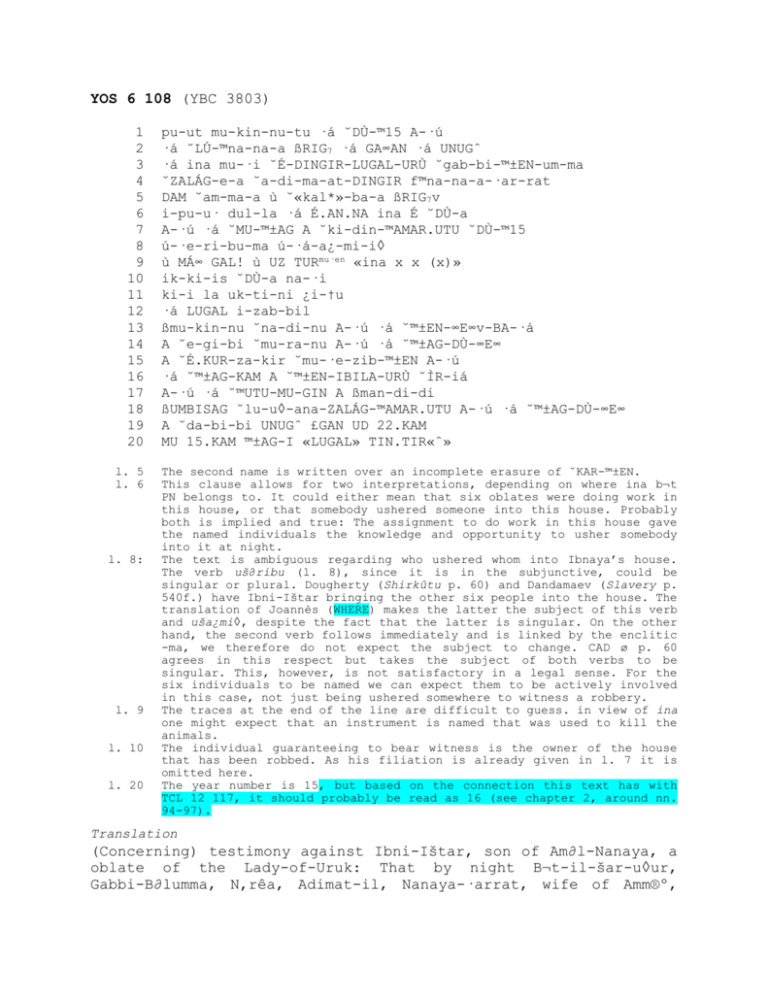

YOS 6 108 (YBC 3803) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 l. 5 l. 6 l. 8: l. 9 l. 10 l. 20 pu-ut mu-kin-nu-tu ·á ˘DÙ-™15 A-·ú ·á ˘LÚ-™na-na-a ßRIG7 ·á GA∞AN ·á UNUGˆ ·á ina mu-·i ˘É-DINGIR-LUGAL-URÙ ˘gab-bi-™±EN-um-ma ˘ZALÁG-e-a ˘a-di-ma-at-DINGIR f™na-na-a-·ar-rat DAM ˘am-ma-a ù ˘«kal*»-ba-a ßRIG7v i-pu-u· dul-la ·á É.AN.NA ina É ˘DÙ-a A-·ú ·á ˘MU-™±AG A ˘ki-din-™AMAR.UTU ˘DÙ-™15 ú-·e-ri-bu-ma ú-·á-a¿-mi-i◊ ù MÁ∞ GAL! ù UZ TURmu·en «ina x x (x)» ik-ki-is ˘DÙ-a na-·i ki-i la uk-ti-ni ¿i-†u ·á LUGAL i-zab-bil ßmu-kin-nu ˘na-di-nu A-·ú ·á ˘™±EN-∞E∞v-BA-·á A ˘e-gi-bi ˘mu-ra-nu A-·ú ·á ˘™±AG-DÙ-∞E∞ A ˘É.KUR-za-kir ˘mu-·e-zib-™±EN A-·ú ·á ˘™±AG-KAM A ˘™±EN-IBILA-URÙ ˘ÌR-iá A-·ú ·á ˘™UTU-MU-GIN A ßman-di-di ßUMBISAG ˘lu-u◊-ana-ZALÁG-™AMAR.UTU A-·ú ·á ˘™±AG-DÙ-∞E∞ A ˘da-bi-bi UNUGˆ £GAN UD 22.KAM MU 15.KAM ™±AG-I «LUGAL» TIN.TIR«ˆ» The second name is written over an incomplete erasure of ˘KAR-™±EN. This clause allows for two interpretations, depending on where ina b¬t PN belongs to. It could either mean that six oblates were doing work in this house, or that somebody ushered someone into this house. Probably both is implied and true: The assignment to do work in this house gave the named individuals the knowledge and opportunity to usher somebody into it at night. The text is ambiguous regarding who ushered whom into Ibnaya’s house. The verb uš∂ribu (l. 8), since it is in the subjunctive, could be singular or plural. Dougherty (Shirkûtu p. 60) and Dandamaev (Slavery p. 540f.) have Ibni-Ištar bringing the other six people into the house. The translation of Joannès (WHERE) makes the latter the subject of this verb and uša¿mi◊, despite the fact that the latter is singular. On the other hand, the second verb follows immediately and is linked by the enclitic -ma, we therefore do not expect the subject to change. CAD ø p. 60 agrees in this respect but takes the subject of both verbs to be singular. This, however, is not satisfactory in a legal sense. For the six individuals to be named we can expect them to be actively involved in this case, not just being ushered somewhere to witness a robbery. The traces at the end of the line are difficult to guess. in view of ina one might expect that an instrument is named that was used to kill the animals. The individual guaranteeing to bear witness is the owner of the house that has been robbed. As his filiation is already given in l. 7 it is omitted here. The year number is 15, but based on the connection this text has with TCL 12 117, it should probably be read as 16 (see chapter 2, around nn. 94-97). Translation (Concerning) testimony against Ibni-Ištar, son of Am∂l-Nanaya, a oblate of the Lady-of-Uruk: That by night B¬t-il-šar-u◊ur, Gabbi-B∂lumma, N‚rêa, Adimat-il, Nanaya-·arrat, wife of Amm®º, and Kalbaya––all temple oblates doing work (on behalf) of Eanna in the house of Ibnaya, son of Iddin-Nabû from the Kidin-Marduk family––ushered him (Ibni-Ištar) at night (into this house), and made (him) commit a robbery; and (furthermore) he killed a goat and a duck with a …: Ibnaya guarantees (to testify). If he does not testify, he will bear a penalty of the king. Witnesses N®din/B∂l-a¿¿∂-iq¬·a//Egibi M‚r®nu/Nabû-b®n-a¿i//Ekur-zakir Mu·∂zib-B∂l/Nabû-∂re·//B∂l-aplu-u◊ur Ardiya/∞ama·-·um-uk¬n//Mandidi Scribe Lû◊i-ana-n‚ri-Marduk/Nabû-b®n-a¿i//D®bib¬ Place and date Uruk, 22nd day, 9th month, year 15 (or 16?) of Nabonidus, king of Babylon. Comments The owner of a house is made to testify in a robbery case commited at his house. Obviously he already has made an accusation but it needs to be heard in court. The ¿¬tu clause against him therefore does not refer to the criminal case as such but to obstructing court procedure. Six named temple oblates who had access to this house for work on behalf of the temple (maybe they were allowed to spend the nights there as well) abused this situation by conspiring to let a burglar in at night. The criminal (also a temple slave), did not only rob but also killed two animals. The way this fact is stated seems to indicate that the people who let him in did not intend him to do this; he rather acted on his own behalf. The criminal charge is twofold: the group of six is accused of instigating and actively supporting a robbery, thereby betraying the trust the temple had bestowed on them, while Ibni-i·tar committed the robbery and killed animals. This case may have an additional twist. The presence of the group of six in Ibnaya’s house is explained by them “doing work on behalf of Eanna”. What sort of work could this be? Why do they stay the night there instead of in the temple precinct? Could there be an implied suspiscion that Ibnaya appropriated temple personnel for his own ends? Is this the main reason why he is made to repeat his accusation––or why he may not wish to do so? Note: YOS 6 108 is also dealt with by Kozuh. Shalom Holtz has a new transliteration of YOS 6 108; he also has a discussion of this, pp. 159ff. Holtz has this guy agrees to testify so the court won’t issue a summons document. Jursa suggests based on what he has said out suggest that this is the Cornelia wants to know testify? older law that this guy has to repeat of court now in court. Cornelia also meaning of I guaranteeing to testify. why this guy has to be compelled to We have looked at YOS 6 208; YOS 7 96, YOS 6 175. The question is whether guaranteeing testimony means that only the guarantor has to testify or whether either the gurantor or the guarantor brings has to testify. Two formulae are used: Put mukinnutu sha and lumukinu abaqu. We have to decide what these mean and whether or not they are the same. In YOS 6 208 Cornelia says, in this case the guy has to testify again because the statement is before the local assembly in a village. This fellow has to come to the real court in Uruk to accuse again. But he does get to bring other evidence. Put mukinnutu sha Put mukinnutu sha is in Cyr 311; Nbn 343; Sack 80; TCL 12 96; YOS 6 108; YOS 6 208; YOS 6 175; YOS 7 96 (according to Shalom Holtz). Translate: Quarantees testimony regarding PN. We don’t know whether they have to testify, they have to repeat what they have said out of court or in a lessor court now in the higher court; or can bring anyone and anything to support their statment. mukinu abaqu Mukinu abaqu is in Nbk 361.365.366.419; OIP 122 34; YOS 7 192. alaku ukinu On the day when...PN1 PN2 lift the head of PN3 then PN3 will alaku ukinu. See e.g., BIN 1 113 he has already given some testimony to the mar bani, the temple officials shall say it before the temple officials and establish his case. Bruce now suggests that the homeowner is under suspicion. He has cut a deal. He will testify against the thief. He will now only be subject to the hitu sha shari and not the 30 fold penalty. So final list: 1) He has to testify to clear himself of negligence supervision. 2a) He has to testify to clear himself of the theft 2b) He made a deal to clear himself that he can’t be prosecuted for theft only 3) He accuses so he has to repeat what he has said out of court or in a lessor court now in the higher court 4) He can bring anyone and anything to cooberate his prior incourt statement. 5) He has improper stuff in his house (people, goods and/or animals) so he does not want to testify at all about this He won’t be tried for theft as represented in YOS 6 175--but there are counter arguments. We have collated this text--it is year 16! So, the knife case is one day before. Cornelia suggests taht the knife is mentioned in this text and is the weapon that was used to slaughter the animals! I think this is a strong possibility and they want our guarantor to nail this guy! Rachel and Bruce’s old remarks: Only four texts contain zabālu: GCCI 2 101, YOS 6 108, YOS 7 116, and YOS 7 192. First, the violation is one that has historically been dealt with by the royal branch of the justice system, such as in a false accusation case (e.g., YOS 6 108).1 He makes other statements that appear to reflect the idea that bearing-sin language does, in fact, refer to a punishment. For instance, with respect to the bearing-sin clause in YOS 6 108, he writes, “A severe penalty was imposed in case of default.”2 Even the documents that contain some duty assumed through either an oath or promise declaration do not all reflect an 1 Joannès, “Textes judiciaire néo-babyloniens,” 208-9. 2 Dougherty, Shirkûtu, 61. See also his comments on YOS 7 177 (“Principle of Suretyship,” 101). exchange.3 A few, for instance, are judicial orders (e.g., YNER 1 2, YOS 6 108, and YOS 7 192). These cannot be viewed as containing a bargained-for-exchange. In some instances, the guarantor is not guaranteeing the appearance of a specific person but, rather, some unnamed witness who can provide specific testimony (YOS 6 108 and YOS 6 175). 3 In the Neo-Babylonian period, contracts rarely contained an oath clause (Oelsner et al., “Neo-Babylonian Period,” 946; cf. C. H. W. Johns, Babylonian and Assyrian Laws, Contracts and Letters [Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1904], 233). Moreover, throughout the ancient Near East, where an oath appears in a contract, it typically addresses peripheral matters and does not bind the party on the primary contractual terms. On this point, Westbrook maintains: “Documents recording the standard contractual forms may also record a promissory oath, by one or both parties. For the most part, the oath relates to ancillary matters: either special terms not usually found in that type of contract, or (most frequently) a promise not to deny, contest, or alter the terms of the completed contract in the future. In the third millennium, oaths are sometimes recorded for central obligations of the contract, e.g. repayment of a loan. This type of oath disappears in the second millennium, where only ancillary oaths are recorded. By the first millennium, it is rare to find any mention of an oath in the records of standard contracts” (“Character of Ancient Near Eastern Law,” 66). YOS 6 108 records a situation in which the court orders a person to guarantee the appearance of a witness.4 The text makes clear that a crime has taken place. Someone has apparently broken into a certain Baniya’s house and killed two temple animals there. The primary suspect is Ibni-Ištar. Six other individuals aided and abetted him, by allowing him to gain entry to Baniya’s house. The court, composed of high-ranking temple officials, does not seem to have sufficient evidence to convict Ibni-Ištar. As a result, the court issues an order to Baniya that he shall serve as a guarantor of “testimony concerning Ibni-Ištar.” This means that Baniya is now required to produce a witness who will provide incriminating testimony against IbniIštar.5 The tablet does not specify exactly whom he will bring; it is Baniya’s responsibility to locate a suitable witness. His household appears to employ a number of servants, including the co-conspirators and possible other eyewitnesses. The court’s probable reasoning then is, because Baniya owns the house, he is the one with the best access to, and control over, the most likely witnesses. The text concludes by stating that, if Baniya does not produce this testimony, “he will bear a sin of the 4 See the Appendix for an edition of this text. Our comments on YOS 6 108 come in large measure from B. Wells, The Law of Testimony in the Pentateuchal Codes, BZAR 4 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2004), 76, 169-71. For other discussions of the document, see Dougherty, Shirkûtu, 60-61; and Joannès, “Textes judiciaire néo-babyloniens,” 209. Cf. Dandamaev, Slavery in Babylonia, 540-41; and M. San Nicolò, “Parerga VII: Der §8 des Gesetzbuches Hammurapis in den neubabylonischen Urkunden,” AnOr 4 (1932) 336. 5 The language of the text indicates that the testimony will disfavor Ibni-Ištar; see Wells, Law of Testimony, 76, 119-20. king.” One could say that the court will cite him for contempt.6 This would be a action based in the administration of the judicial system. YOS 7 192 seems primarily to be about theft.7 Its conditional verdict refers to the standard thirty-fold penalty for theft of temple property and to bearing a sin of the king. As is typical with conditional verdicts, the condition that must be met before the verdict takes effect is that a witness come forward and offer testimony incriminating the defendant. The text begins with an oath that is sworn by the defendant, Šamašmudammiq. He avows his innocence, by stating that he did not take a temple donkey from the possession of a certain Bel-lumur, nor did he carry off the message of Nabugu that was in Bellumur’s possession. The conditional verdict follows. It states that when Bel-lumur is able to bring a witness who can incriminate Šamaš-mudammiq on these two counts, then he (Šamašmudammiq) will be required to pay thirty donkeys to the temple and will bear a sin of the king. Because Bel-lumur has the 6 This is contrary to the view of Joannès, who states that bearing a “sin of the king” in this text refers to punishment for false testimony (Joannès, “Textes judiciaire néo-babyloniens,” 208-09). Joannès is, however, assuming that Baniya’s testimony has already been heard by the judges and that Baniya now bears an obligation to produce a corroborating witness. If he should fail, according to Joannès, the court will deem his testimony false. Even if Joannès should be right that Baniya gave testimony before YOS 6 108 was drawn up, there are no other occurrences of the bearing-sin language that support this conclusion. Furthermore, persons appear to have been found guilty of false testimony in the Neo-Babylonian period only when they are guilty of wrongful prosecution and their accusation has been clearly refuted (see Wells, Law of Testimony, 149-55). 7 See the Appendix for an edition of this text. See additionally, G. Ries, “Zur Strafbarkeit des Meineids im Recht des Alten Orients,” in Festschrift für Dieter Medicus zum 70. Geburtstag, ed. V. Beuthien et al. (Cologne: Heymanns, 1999), 463-64; cf. San Nicolò, “Der §8 des Gesetzbuches Hammurapis,” 336 n. 1. responsibility to produce additional evidence, he is undoubtedly the accuser in the case. Moreover, as the one who had possession of the donkey and the message of Nabugu, Bel-lumur was probably the one assigned to deliver it. This may also mean that he has better access than others to evidence and that the court holds him partly responsible for helping to resolve the situation (as was true for Baniya in YOS 6 108).