HIST 351 - WordPress.com

advertisement

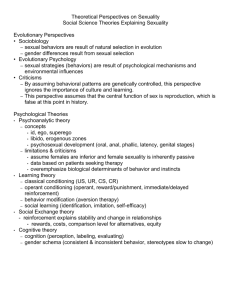

HIST 351- Winter Term 1 2013 History of Gender and Sexuality in Latin America Calendar detail: Role of gender and sexuality from colonial period to the present. The role of the family and the community in reinforcing sexual and gendered roles. [3-0-0]Prerequisite: 6 credits of HIST, or 3rd year standing and one of HIST 240 or HIST 241. Class times: W, F 12:30-1:50pm ART 204 jessica.stites-mor@ubc.ca Office: ART 242 Hours: Mon 11-12 www.elearning.ubc.ca/connect Naj Tunich, Mayan Cave Painting “The time has come to think about sex. To some, sexuality may seem to be an unimportant topic, a frivolous diversion from the more critical problems of poverty, war, racism, famine, or nuclear annihilation. But it is precisely at times such as these, when we live with the possibility of unthinkable destruction, that people are likely to become dangerously crazy about sexuality. Contemporary conflicts over sexual values and erotic conduct have much in common with the religious disputes of earlier centuries. They acquire immense symbolic weight. Disputes over sexual behavior often become the vehicles for displacing social anxieties, and discharging their attendant emotional intensity. Consequently, sexuality should be treated with special respect in times of great social stress. “The realm of sexuality also has its own internal politics, inequities, and modes of oppression. As with other aspects of human behavior, the concrete institutional forms of sexuality at any given time and place are products of human activity. They are imbued with conflicts of interest and political maneuvering, both deliberate and incidental. In that sense, sex is always political. But there are also historical periods in which sexuality is more sharply contested and more overtly politicized. In such periods, the domain of erotic life is, in effect, renegotiated.” -Gayle Rubin G. Rubin, “ Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” Culture, Society, and Sexuality: A Reader. Ed. Richard Parker and Peter Aggleton. New York: Routledge, 1999. 143. Detailed Description: This course will examine a range of historical issues around the concepts of gender and sexuality in Latin America. The course traces the development of gender and sexuality theory through its application in recent historical research on the subject in a variety of settings, including Meso-America, the Caribbean, Brazil, the Southern Cone, and the Peruvian Andes. Readings and discussions will center on five major themes that signal significant transformations in sexual- and gender-based identities and social roles: indigenous practices at the time of conquest; the process of colonization; the construction of independent nation-states; revolutionary struggle; and the era of globalization and U.S. neo-imperialism. Course Objectives: Students that successfully complete this course will be able to: Identify major themes of the history of sexuality and gender in Latin America and situate them within historical and geographic contexts. Understand developments within the critical theory on sexuality and gender and apply them to historical topics. Take a critical position and present coherent arguments on gender and sexuality issues in the form of a research paper. Demonstrate competency and oral skills in class discussions. Required Texts: Sigal, Pete. From Moon Goddesses to Virgins: The Colonization of Yucatecan Maya Sexual Desire. Austin: University of Texas, 2000. ISBN 0292777531 Burns, Katherine. Colonial Habits: Convents and the Spiritual Economy of Cuzco, Peru. Durham, Duke University Press, 1999. ISBN 0822322919 Restrepo, Laura. The Dark Bride. New York: Harper Perennial, 2003. ISBN 0060088958 Hershfield, Joanne. La Chica Moderna: Woman, Nation and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1917-1934. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. ISBN 9780822342380 Green, James. Beyond Carnival: Male Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century Brazil. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1999. ISBN 0226306399 Brennan, Denise. What’s Love Got to Do with It? Transnational Desires and Sex Tourism in the Dominican Republic. Durham: Duke University, 2004. ISBN 0822332973 Student Evaluation: Four in-class essays 10% each (40% total) Participation in class discussion 10% Novel analysis 10% (3 -5 pages) Film analysis 10% (3 - 5 pages) Final Exam 30% (Take home) Extra credit option: Additional Film critiques are worth up to 2% each towards final grade, max 5% Weekly schedule: Week 1- Introduction to gender and sexuality in Latin America (Sept 4, 6) A- What is gender? What is sex? Recommended: Joan Scott, “Gender, a Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” American Historical Review 91.5 (1986): 1053-75. Pictographic sign (Glyph T761) for male genitalia, used as a title in Classic Maya inscriptions. B- Sexuality and the Primitive Savage Start Sigal – Chap 1-3 Recommended: Marianna Torgovnik. “Defining the Primitive/Reimagining Modernity,” in Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. 3-41. Questions: 1) What is sexuality in ancient indigenous American societies? 2) How did indigenous societies understand homosexuality? 3) How did gender relate to power and social hierarchy? 4) How did the Maya understand sexual behavior? 5) What defined Mayan masculinity or femininity? 6) Is it possible to reconstruct pre-Columbian sexual ideologies? What evidence can be used by the historian to understand sexuality in the ancient past? 7) How does the Judeo-Christian filter of accounts of the past shape our understanding of gender and sexuality in non-Western cultures? Week 2- Modes of Reproduction (Sept. 11, 13) A- Rituals of Kinship and Community Sigal – Chap 4-6 Recommended: Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution.” Theatre Journal. 40.4 (1988): 519-531. B- Reproducing Empire Sigal – Chap 7-10 Recommended: Sherry Ortner. “Gender Hegemonies.” Cultural Critique. 14 (Winter 1988-1989): 35-80. Questions: 1) How do kinship relations script gender roles and sexual customs? 2) How are class and gender identities related to one another? 3) Are gender roles performative? 4) What is the role of blood in determining social relationships in ancient Mesoamerica? 5) How does the state utilize marriage and reproduction as means to reinforcing power relations and social hierarchies? Week 3- Sex and Conquest (Sept. 18, 20) A- The Colonizer and the Colonized Burns – Introduction, Part One Recommended: Ann Laura Stoler. “Tense and Tender Ties.” Journal of American History. 88.3 (2001): 829-865. B- FIRST IN-CLASS ESSAY (Sept 20) Questions: 1) How does the paradigm of conquest color gender relations during the initial encounter of Europeans and indigenous peoples in the New World? 2) How is sexuality related to colonization? 3) How did the Spanish understand their sexual experiences during colonization? 4) Did the colonization process affect the sexuality of the colonizers? 5) What social, political, and economic issues were raised by the practices of “sexual conquest” of the Americas? 6) How was gender renegotiated in the process of imperial expansion in Mesoamerica and the Andes? Catalina de Erauso, “Lieutenant Nun” Week 4- Sexual Control and Sexual Deviance (Sept. 14, 27) A- Bodies, Souls and the Catholic Church Burns – Part Two Recommended: Michel Foucault. “The Subject and Power.” Critical Inquiry. 8.4 (1982): 777-795. B- Crime, Witchcraft and Sins of the Flesh Burns – Part Three Recommended: Max Kirsch, “Queer Theory, Late Capitalism, and Internalized Homophobia.” Journal of Homosexuality. 52.1 (2007): 19-45. “El Chalequero” José Guadelupe Posada Questions: 1) What role did the church play in determining gender and family relationships? 2) Did the organization of a dual authority system, between civil and canonical law, impact the gendered struggles of colonial life? 3) How did colonial racial constructions prefigure sexual and gender relations in colonial Latin America? 4) How did the religious orders structure and maintain their influence on sexual practices in the Americas? 5) What role did deviance play in revealing the fissures of authority in colonial gender relations? 6) What kind of forms of resistance did the crown and/or the Catholic church tolerate and why? Week 5- Policing the Nation, Policing the Body (Oct. 2, 4) A- Honor, Family, and Civil Codes in the long 19th century Restrepo - pages 1-90 Recommended: Sherry Ortner, “The Virgin and the State” Feminist Studies. 4.3 (1978) 19-35. B- SECOND IN-CLASS ESSAY (Oct. 4) Restrepo – 91- 173 Week 6- Intimacies of Knowledge (Oct. 9, 11) A- Scientific Reproduction and Medicalized Sexuality Restrepo – 174-261 Recommended: Peter Conrad, “Medicalization and Social Control.” Annual Review of Sociology. 18 (1992): 209-232. B- Gendered Media Restrepo – 262- 358 Recommended: Joan Kelly, “Early Feminist Theory and the ‘Querelle des Femmes’, 1400-1789,” Signs, 8.1 (1982): 4-28; and Elaine Showalter, “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness,” Critical Inquiry. 8.2 (1981): 179-205. Questions: 1) How did legal and medical discourses come to define social norms of sexual behavior in the 19th century in Latin America? 2) Upon what kind of bases did sexual crimes become public knowledge, how were they interpreted, and eventually how were they handled? 3) How did Porfirian moral reformism impact gender roles in late 19th century Mexico? 4) How were science, hygiene, and medicine implicated in the business of building the nation-state? 5) What did the presence of women writers in the popular press mean for the representation of gender and gender issues in the media? 6) How did women defend their interests against and by using positivist discourses? Week 7- Inscribed on the Body (Oct. 16, 18) A- Physicality, Corporeality, and Body Parts Hershfield - Introduction and Chap. 1 Recommended: Judith Butler, “Variations on Sex and Gender,” The Judith Butler Reader. Ed. Sara Salih. Malden, Massachussetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. 21-38. B- Transgressivity and Expression Hershfield - Introduction and Chap. 1 Madam Satã, Karim Aïnouz, 2002 **Novel Paper Due (Oct. 18) Questions: 1) What meanings did Frida Kahlo give to the body that challenged traditional Mexican ideas of sexuality and gender? 2) How were transgressive expressions of individual sexuality or gender identities, such as crossdressing and homosexuality, viewed by Brazilian society in the 1930s? 3) What kind of “corporeality” did gender politics express in early 20th century Latin America? Week 8- Political Economy of Sex and Gender (Oct. 23, 25) A- Gender-based Politics and Social Movements Hershfield – Chap. 2-3 Recommended: bell hooks, Feminist Theory from Margin to Center, Boston: South End Press, 1984. B- Masculinity, Sport and National Identity Hershfield – Chap. 4-5, Conclusion Recommended: Joane Nagel, “Masculinity and Nationalism: Gender and Sexuality in the Making of Nations.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. 21.2 (1998): 242-269. Also Michael Messner. Power at Play: Sports and the Problem of Masculinity. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992. Questions: 1) How have women’s movements related to other political and social demands for reform or revolution in Latin America? 2) Are women’s emancipation and equality movements necessarily tied to left-leaning political movements? 3) What are women’s strategic and practical goals in their gender- based political activism? 4) How does futbál or futebol in Latin America relate to the social construction of masculinity? Isabel Sarli, Argentine actress, Thunder among the Leaves Week 9- Modernity, Sexual License and Gender Roles (Oct. 30, Nov. 1) A- THIRD IN-CLASS ESSAY (Oct. 30) Green – Intro, Chapter 1 B- Revolutionary Women and Gay Men Green – Chpater 2-3 Questions: 1) What unique problems did socialist revolutions cause for women’s liberation in Nicaragua and Cuba? 2) What limitations did reform measures passed in the 1960s and 1970s face in making major changes to family life and gender roles in Cuba? 3) Can women’s politics be viewed as independent of other political and social movements? Week 10 - Erotica, Desire, and Love (Nov. 6, 8) A- Pornography and Erotic Literature Green – Chapter 4-5 Recommended: Catharine MacKinnon. Only Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993. Also, Angela Carter “Polemical Preface: Pornography in the Service of Women,” The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography. New York: Pantheon Books, 1979, 3-19. B- Sexual Tensions of Desire and Love Green – Chapter 6-7 Recommended: Andrea Dworkin. Intercourse. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997. Questions: 1) Are desire, arousal, and sexual gratification political issues? 2) Why have pornographic images and texts viewed by the state as threatening in Brazil and Mexico? 3) What relationship does love or desire have to culturally constructed expectations about gender roles and sexuality? 4) Does the emotional experience of love differ between cultures, time periods, and situations? Week 11- Laboring Bodies (Nov. 13, 15) A- Transnational Bodies Brennan – Introduction, Chap 1-2 Recommended: Gayle Rubin. “Traffic in Women: Notes on the ‘Political Economy’ of Sex,” in Feminist Anthropology: A Reader. New York: Blackwell, 2006. 87-106. Nicole Constable, “The Commodification of Intimacy: Marriage, Sex, and Reproductive Labor.” Annual Review of Anthropology. 38 (2009): 49-64. B- Persistent Inequalities (Class discussion and review) Brennan – Chap 3-4 **Film Paper DUE (Nov. 15) Questions: 1) How does the “exotic other” play into the market and the cultural imaginary of the sex trade in tourist economies? 2) To what extent are sex workers exploited by tourists, and to what extent are they agents in reproducing patterns of sexual encounter and exchange? 3) How do sex tourists understand their relationship to host countries and what might this say about their perceptions of gender and sexuality in their own home countries? 4) What inequalities persist between genders and different sexual identities in contemporary Latin America? 5) How have identitarian political movements impacted gender-related political struggles? Week 12- Wrap-up (Nov. 20, 22, 27) A- FOURTH IN-CLASS ESSAY (Nov. 22) **Take home FINAL is due Nov. 29 Course Policies: Attendance at lectures, discussions, and film screenings is mandatory. All deadlines, either on the syllabus or announced in class, should be considered inflexible. Any assignments turned in after the due date will be marked down accordingly. In general, papers are deducted one letter grade for each day the assignment is late. Extensions will be granted only in the case of unforeseen emergency. If legitimate problems arise during the course of the semester which might delay finishing written work or hinder attendance, students should communicate with the professor prior to the scheduled events. In the event of serious illness, death in the family, or other legitimate concern, formal documentation may be required. Any work delivered to the department instead of in class will be time-certified by the secretary. DISABILITY RESOURCES: If you require disability related accommodations to meet the course objectives please contact the Coordinator of Disability Resources located in the Student development and Advising area of the Student Services Building. For more information about Disability Resources or about academic accommodations please visit the website at http://okanagan.students.ubc.ca/current/disres.cfm ACADEMIC INTEGRITY: The academic enterprise is founded on honesty, civility, and integrity. As members of this enterprise, all students are expected to know, understand, and follow the codes of conduct regarding academic integrity. At the most basic level, this means submitting only original work done by you and acknowledging all sources of information or ideas and attributing them to others as required. This also means you should not cheat, copy, or mislead others about what is your work. Violations of academic integrity (i.e., misconduct) lead to the break down of the academic enterprise, and therefore serious consequences arise and harsh sanctions are imposed. For example, incidences of plagiarism or cheating usually result in a failing grade or mark of zero on the assignment or in the course. Careful records are kept in order to monitor and prevent recidivism. A more detailed description of academic integrity, including the policies and procedures, may be found at http://web.ubc.ca/okanagan/faculties/resources/academicintegrity.html. If you have any questions about how academic integrity applies to this course, please consult with your professor. Style Guide for Citation of References in Writing: The History faculty has adopted a guide to follow for the submission of all History papers. Students are expected to submit all papers in lower level history courses in the format as defined in the style guide. This guide is available for purchase in the bookstore. Copies are also on reserve in the library. This text is: Mary Lynn Rampolla, A Pocket Guide to Writing History (Bedford Books). Marks: A range (80% to 100%) A+ (90% +) A (85-89%) A- (80-84%) Exceptional performance. Superior grasp of subject matter with sound critical evaluations. Evidence of extensive knowledge of the literature. Superior organization and use of evidence. Persuasive composition. Reflects having benefited from revision. B range (68% to 79%) B+ (76-79%) B (72-75%) B- (68-71%) Competent performance. Clear grasp of the subject matter and appropriate use of evidence. Some evidence of critical and analytical ability. Demonstrated familiarity with the literature. Clear composition. C range (60 to 67%) C+ (64-67%) C (60-63%) Satisfactory performance. Basic understanding of the subject matter. Demonstrated ability to develop solutions to basic problems with the issues and material. Acceptable but uninspired presentation that is not generally faulty but lacks style and depth. Generally flawed composition. D to C- range (50-59%) C- (55-59%) D (50-54) Minimal acceptable performance. Familiarity with material and themes but no consistent analytical or expository qualities. Usually awkward, difficult composition and/or organization. F range (0 to 49%) Inadequate performance. Little or no evidence of understanding of the subject matter or use of materials. Weak critical and analytical quality. Substandard composition and/or failure to meet the technical requirements for the assignment. Grammatical mistakes which exceed the accidental.