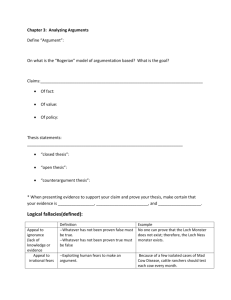

Appeal to authority:

advertisement

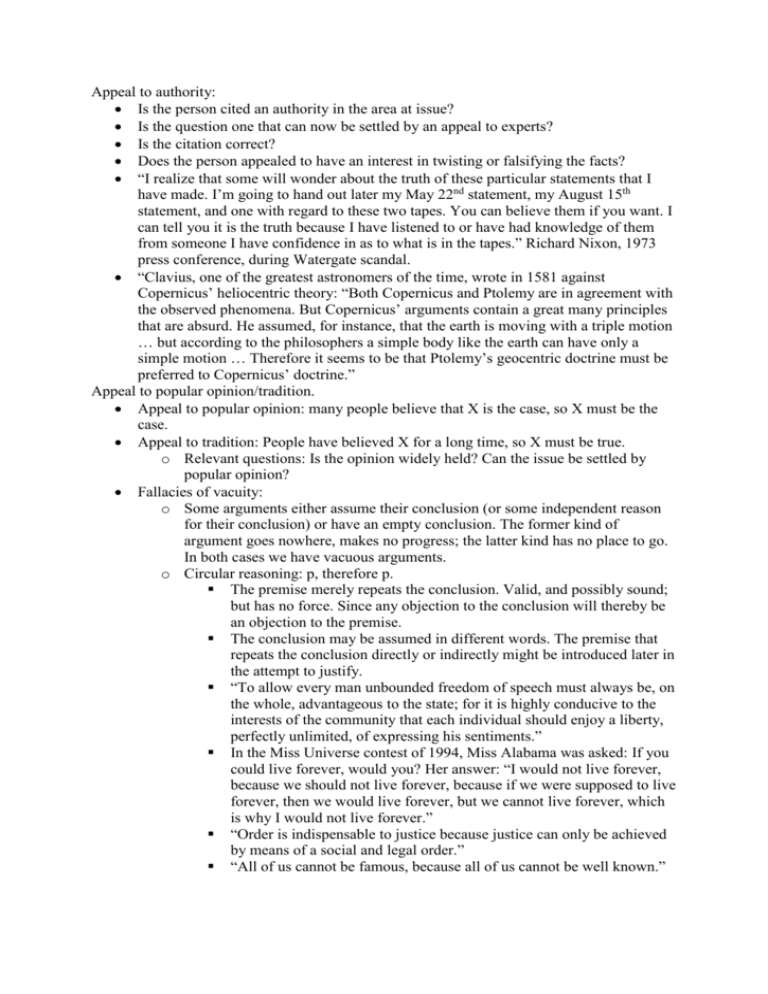

Appeal to authority: Is the person cited an authority in the area at issue? Is the question one that can now be settled by an appeal to experts? Is the citation correct? Does the person appealed to have an interest in twisting or falsifying the facts? “I realize that some will wonder about the truth of these particular statements that I have made. I’m going to hand out later my May 22nd statement, my August 15th statement, and one with regard to these two tapes. You can believe them if you want. I can tell you it is the truth because I have listened to or have had knowledge of them from someone I have confidence in as to what is in the tapes.” Richard Nixon, 1973 press conference, during Watergate scandal. “Clavius, one of the greatest astronomers of the time, wrote in 1581 against Copernicus’ heliocentric theory: “Both Copernicus and Ptolemy are in agreement with the observed phenomena. But Copernicus’ arguments contain a great many principles that are absurd. He assumed, for instance, that the earth is moving with a triple motion … but according to the philosophers a simple body like the earth can have only a simple motion … Therefore it seems to be that Ptolemy’s geocentric doctrine must be preferred to Copernicus’ doctrine.” Appeal to popular opinion/tradition. Appeal to popular opinion: many people believe that X is the case, so X must be the case. Appeal to tradition: People have believed X for a long time, so X must be true. o Relevant questions: Is the opinion widely held? Can the issue be settled by popular opinion? Fallacies of vacuity: o Some arguments either assume their conclusion (or some independent reason for their conclusion) or have an empty conclusion. The former kind of argument goes nowhere, makes no progress; the latter kind has no place to go. In both cases we have vacuous arguments. o Circular reasoning: p, therefore p. The premise merely repeats the conclusion. Valid, and possibly sound; but has no force. Since any objection to the conclusion will thereby be an objection to the premise. The conclusion may be assumed in different words. The premise that repeats the conclusion directly or indirectly might be introduced later in the attempt to justify. “To allow every man unbounded freedom of speech must always be, on the whole, advantageous to the state; for it is highly conducive to the interests of the community that each individual should enjoy a liberty, perfectly unlimited, of expressing his sentiments.” In the Miss Universe contest of 1994, Miss Alabama was asked: If you could live forever, would you? Her answer: “I would not live forever, because we should not live forever, because if we were supposed to live forever, then we would live forever, but we cannot live forever, which is why I would not live forever.” “Order is indispensable to justice because justice can only be achieved by means of a social and legal order.” “All of us cannot be famous, because all of us cannot be well known.” o Begging the question: x, therefore y, where x is not supported by any reason that is independent of the conclusion and where we do need such an independent reason. Three formulations to understand what is involved: a) One could not have any reason to believe the premise if one did not already have the same reason to believe the conclusion, b) the reason to believe the premise depends on one’s prior belief in the conclusion (or on one’s reason to believe the conclusion), c) one has no independent reason for the premise. Again, rejecting the conclusion will amount to rejecting the premise. “Granted, it is altogether true that we must believe in God’s existence because it is taught in the Holy Scriptures, and conversely, that we must believe the Holy Scriptures because they have come from God. This is because, of course, since faith is a gift from God, the very same one who gives the grace that is necessary for believing the rest can also give the grace to believe that he exists. Nonetheless this reasoning cannot be proposed to unbelievers because …” Descartes, Letter of Dedication (of the Meditations). Principle of induction: Laws of nature will operate tomorrow as they operate today: since nature is uniform, we may rely on past experience to guide our conduct in the future: the future will be essentially like the past. By way of proof we can offer the following: in the past the principle of induction has always held. But the point at issue is whether nature will continue to behave regularly. That it has done so in the past cannot be invoked to establish that it will do so in the future without assumed the very principle that is in question: that the future will be like the past. Hume: how can we know that future futures will be like past futures. They may be so, but we cannot assume that they will be in the effort to prove that they will. In a film featuring the comedian Sacha Guitry, some thieves are arguing over division of seven pearls worth a king’s ransom. One of them hands two to the man on his right, then two to the man on his left. “I,” he says, “will keep three.” “How come you keep three?” “Because I am your leader.” “Oh. But how come you are the leader?” “Because I have more pearls.” o Self-sealer: A position so constructed that no evidence can possibly be brought against it. This renders it vacuous. Falsification/verification. Karl Kraus and psychoanalysis. Universal discounting: all criticism explained away by ad hoc claims. Attack the critic (usually by ad hominem charges). Construct the position to establish its truth by definition. “There is no such thing as knowledge which cannot be carried into practice, for such knowledge is no knowledge at all.” Wishful thinking: Takes two forms, which are flipsides of the same coin: o The awful consequences of a claim’s being true (or believing it) are taken to be a reason for rejecting it. o The awful consequences of a claims being false are taken to be a reason for accepting it. o In either case, our desire for a particular outcome is taken to be the ground on the basis of which the truth or falsity of that outcome is decided. This may provide solace or comfort, but more often than not—and alas—it has little to do with the conclusion. o “I don’t believe that we cease entirely when our bodies die. I mean, if I thought it was all going to be over, I just couldn’t stand it.” o We tend to recognize this fallacy easily when others commit it; however, we usually let it pass when we are the ones committing it. o Nietzsche’s argument in Antichrist. o What about “positive thinking”? Hasty generalization: When we draw conclusions about all persons or things of a class on the basis of our knowledge about only one or very few of the members of that class. o It is a case of defective induction. o The owner of a fish and chips shop in England defending the healthfulness of his deep-fried cookery with the following argument: “Take my son, Martyn. He’s been eating his fish and chips his whole life, and he just had a cholesterol test, and his level is below the national average. What better proof could there be than a fryer’s son?” False cause: Presuming the reality of a causal relation/connection that does not exist gives rise to this type of fallacy. o The causal connection may be in dispute; hence whether it is mistaken may be contentious. o There are some forms, however, that tend to generate mistaken causal claims: Mistaking temporal succession for causal connection. (post hoc ergo propter hoc: after the thing, therefore because of the thing. The following passage by critic of a US Congressman draws attention to this fallacy: “I am getting tired of assertions like those of Rep. Ernest Istook, Jr.—‘As prayer has gone out of the schools, guns, knives, drugs, and gangs have come in’—with the unsupported implication that there is some causal connection between these events.… We could just as well say, ‘After we threw God out of the schools, we put a man on the moon.’ Students may or may not need more faith, but Congress could certainly use more reason.” “Which is more useful, the Sun or the Moon? The moon is more useful since it gives us light during the night, when it is dark, whereas the Sun shines only in the daytime, when it is light anyway.” “My generation was taught about the dangers of social diseases, how they were contracted, and the value of abstinence. Our schools did not teach us about contraception. They did not pass out condoms, as many of today’s schools do. And not one of the girls in any of my classes, not even in college, became pregnant out of wedlock. It wasn’t until people began teaching the children about contraceptives that our problems with contraceptives began.”